My parents are practical people, conventional in their thinking. They raised me with the usual ideas about good and evil. One was easily attainable if you obeyed the Commandments, flossed daily and followed the Golden Rule. The other stemmed from exotic temptations the average person didn’t have to worry about.

I met Tracy Pasco in the spring of 1980—in my Pennsylvania hometown, a time of relative optimism and ease. The local industry, coal mining, would in a few years falter and eventually fail completely, and hundreds of families would pick up and leave. At the time no one saw this coming, though we should have: the Mineworkers’ dealings with management had grown increasingly shrill. But the union’s blind stubbornness was seen, for a long time, as toughness; and my father’s job at the mine—he was a shift boss—seemed perfectly secure. Bakerton in 1980 was still a working-class town, neither rich nor poor; its junior high small enough that the arrival of a new pupil, late in the school year, qualified as an event. My class’s initial fascination with Tracy was due less to his own qualities than to our intense boredom with each other; by the eighth grade we were all familiar as cousins. Children are ruthless in their recall, particularly when the memory involves some bodily humiliation. Lord help the classmate who threw up in the gymnasium, who wet his pants in kindergarten. His disgrace will follow him all his days. In this way Tracy had an edge over the rest of us, despite his girl’s name. His history was a mystery—his family, his temperament, his early failures, and shames.

I’d have called him an ordinary-looking boy—curly hair, freckles, a crooked eyetooth. But females are the real judges of male attractiveness, and my sister, who was not prone to such rhapsodies, once described his eyes as crystal blue. Nina was just a year older but miles ahead of me socially. From an early age I recognized her general superiority: the better student, popular in school, chipper and helpful around the house. She was even good at sports, the one area where I might have dominated. My parents must have regretted not quitting while they were ahead.

That Nina and her high school friends were aware of Tracy Pasco was, to me, a stunning discovery. The girls in my own class tracked him like a pack of hunting dogs. I was too young for a girlfriend, but not for girls. The eighth grade had several pretty ones I studied with more or less equal interest. The Pantheon, I called them: Beth Leggett, Melissa Wyman, Robin Godfrey, Tara Sneed. Their giggling curiosity about Tracy frankly dismayed me, though I hoped to use it to my advantage.

In those days our teachers seated us, unimaginatively, in alphabetical order—Pasco, Patterson—and I saw my opportunity. When Tracy came to class without a pencil or loose-leaf notebook paper, I was quick to offer him mine. Later, when Beth Leggett cornered me in the hallway, I revealed the following facts: Tracy came from an army base in Texas, where his father had been stationed; and was an only child—at the time, a rarity in our town. His mother was dead, his father raised in a farmhouse on Number Nine Road, not far from my own house, where he and Tracy now lived. These few biographical details were all I had to offer, and I’d planned to withhold them as long as possible, doling them out strategically to sustain multiple conversations with multiple girls. Instead I told Beth everything the moment she asked.

“Dead?” she repeated in a whisper. “Nathan, are you sure?” She was strawberry-blonde and precociously shapely, with breasts—I might have called them “bosoms”—like a grown woman. I was glad for any excuse to talk to her, even about another boy.

“He wouldn’t make that up,” I said.

“Well, what did she die of?”

“How should I know?”

Beth glanced over my shoulder. I sensed her interest flagging.

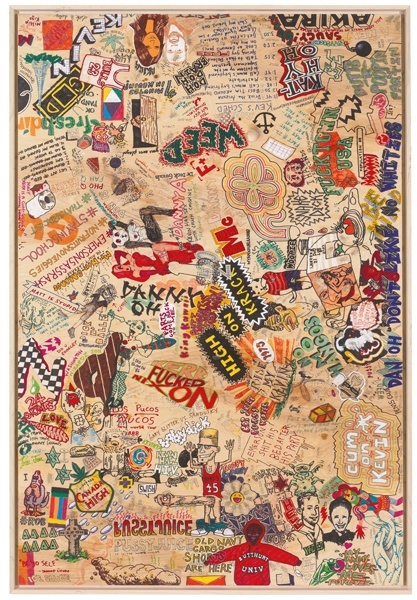

“I’ll find out,” I said—though how exactly I would do this wasn’t clear. Tracy was a quiet boy. Though he looked like an athlete—taller than average, and well-muscled—he hadn’t signed up for Boys’ Intramurals. In class he sketched or doodled constantly. Other boys drew the same things—cars, boats, dinosaurs, airplanes—but without Tracy’s skill.

All these years later, her face is a blank to me. I remember only her hair, worn in the style of a popular TV actress who’d kindly posed in a red swimsuit in order to be displayed on my bedroom wall, animating my puberty.

Once he was caught in the act. Our English teacher that year was a woman named Ginny Seaver—a new hire, fresh out of the state university. I didn’t realize at the time just how young she was. She owned a yellow Ford Mustang, the only one in town. Occasionally I saw her driving to school, the windows down, the radio playing the same music I listened to: Electric Light Orchestra, Led Zeppelin, the Who. All these years later, her face is a blank to me. I remember only her hair, worn in the style of a popular TV actress who’d kindly posed in a red swimsuit in order to be displayed on my bedroom wall, animating my puberty. Miss Seaver may have looked nothing like her, beyond the hairdo; but in my erotic imagination they were one and the same.

In class she paced the aisles as she lectured, filling the air with a flowery perfume. One morning she halted beside my desk to look over Tracy’s shoulder. “Tracy! Art isn’t until fifth period.” Even while scolding her tone was gentle, teasing. I noticed everything about her: her bare white arms, the red imprint left by her watchband, a long blonde hair clinging to her skirt.

Quickly Tracy closed his notebook. The tips of his ears, I saw, were flaming red.

“Let me see,” Miss Seaver said. Grudgingly he opened the notebook. She leaned down and studied it intently. I watched her in a kind of trance, noting the square outline of her bra through the back of her blouse.

“This is very good,” she said softly, sounding surprised. “Come see me after class.”

“She wanted to look at my drawings,” Tracy explained later, as we walked down the hall after the final bell.

I was queasy with jealousy. “What for?”

“What’s an Art Fair?”

I explained that it was held every spring at the high school, to showcase the best work by high school students. In rare cases a junior-high kid was included. My sister Nina, annoyingly, had been one such prodigy.

Tracy smiled halfway, hiding his crooked tooth. “She was sitting at her desk. I got a good look down her blouse. She has little titties.” He opened the notebook under his arm. “I think I got them right.”

He flipped to a page at the back of the book. If I close my eyes I can still see it: a pencil sketch of a naked woman, faceless, her arms bound behind her, her body lashed around the middle to a tree. When I recall it now, it’s the position that shocks me, though at the time I was mesmerized by the anatomical features: the nipples rendered in meticulous detail, the dark shading between the legs. From what little I’d seen of female nudity (in a neighbor’s basement, his dad’s collection of old Playboys), Tracy’s sketch was alarmingly accurate. I stared mutely, overcome by waves of feeling: anger, fascination, jealousy, and shame.

“She didn’t see this one. I flipped right past it. I pretended like the pages were stuck together. That was a close call,” Tracy said, a note of exhilaration in his voice.

We never talked about the drawing again, but I thought about it a great deal. My own nascent sexual impulses—furtive, anxious—were a rich source of embarrassment. It was unnerving to get a look at someone else’s.

Without any great effort on either part, we became friends. For boys that age, it’s a simple matter: place them a few times in each other’s path, and barring some outsized display of aggression from one or both, they will get along well enough. Our friendship was based on proximity. We lived on the same side of town and fell into a habit of walking together to and from school. One benefit of this arrangement was that girls often walked behind us, close enough to hear our conversation, when there was any, and chime in.

I’ve tried to remember what we talked about. TV, mainly. (I recall one show we particularly liked, a mid-season replacement, that featured home videos of misbehaving family pets.) More often than they’d have guessed, we discussed our teachers. Like most boys our age, we adopted a smart-aleck stance toward the adults in our lives—their clothing and mannerisms, the idiotic things they said. For me—for most of us, I suspect—it was a hollow pose. That parents and teachers generally liked me had given me, always, a feeling of security and well-being, something I would understand only years later, after I had squandered their regard.

The Art Fair was held in the last week of school, a Tuesday. My family went together, piled into our minivan: my parents up front, behind them Nina and our grandmother. I had the rear-facing seat all to myself. It was, altogether, a familiar scene. For years I’d been dragged to Nina’s choral concerts and ballet recitals, her science fairs and spelling bees.

The high school cafeteria had been divided with rows of tall screens. Pinned to them were charcoals and watercolors, etchings and photographs. There were table displays of ceramic pottery, figurines in papier-mâché. My sister’s drawing hung in the first row, a pen-and-ink sketch of Gram (who’d been brought along, I cynically believed, as living evidence of Nina’s artistic talent.) Two women teachers stood studying the portrait. When our family approached, with Gram up front, they commented on the likeness.

“Nina, this is just marvelous,” one said. Then, lowering her voice. “It should have won a ribbon, in my opinion. An honorable mention, at least.”

Nina blushed prettily. She didn’t expect to win anything, she insisted. She was only a freshman; she had plenty of time.

Even her humility irked me. “Can we go now?” I asked, but my parents were already ten paces ahead, studying a woodblock print of a sailboat that, in my view, a toddler might have made. The Art Fair, clearly, was going to take all night. I lingered far behind, looking for girls; but the only ones I saw were in high school and thus too terrifying to talk to. Still, they were more interesting than calligraphy or macramé.

I stopped to study a pencil drawing of an airplane. A bright red ribbon was pinned beside it. The picture was unsigned, but clearly labeled: Tracy Pasco, Grade 8. On the surrounding wall were other sketches, by juniors and seniors mostly. The only eighth-grader in the entire show had won second place! Later, on the drive home, I crowed as though it were my own personal triumph. Even Nina hadn’t won a ribbon at that age.

I congratulated Tracy the next morning as we were walking to school. “Second place, that’s unbelievable. The first place drawing was by a senior. A senior,” I repeated for emphasis. “Yours was better, though.”

It was raining, I remember. My mom had made me wear a slicker, but Tracy’s shirt was getting wet. By the time we got to school it would be plastered to his back.

I remember him flushed and tongue-tied. I remember being a little afraid, because he looked ready to pop me one.

He stared at me as though I’d lost my mind.

“My 747 was in the Art Fair?” His face reddened. “She asked me if I wanted to be in it. I didn’t know what it was, so I told her no.”

It took me a moment to understand that he meant Miss Seaver. “Maybe she wanted to surprise you.”

“How did she get my picture?”

“Mrs. Neugebauer”—the art teacher—“must have given it to her.” I stared at him, mystified. Honestly, why did it matter? Tracy had won a contest he hadn’t even entered. There was no greater victory in life.

I remember him flushed and tongue-tied. I remember being a little afraid, because he looked ready to pop me one.

“I told her no,” he said.

“I was never all that good,” Nina says now—still, after everything, modest to the core. “Certain people just have it, this way of seeing. I didn’t. I was diligent. And, you know, over-praised.”

She fumbles for the remote control, which is not actually remote—it’s attached to the bed by a thick electrical cord—and finds the button to raise her feet. The art supplies I brought last time—a thick pad and pastels, still in their shrink-wrapped box—lie on the wheeled table beside the bed. A nurse or Nina herself must move them three times a day, so Nina can eat her meals.

“I hit a point where I just stopped improving. Other people kept getting better, but I was as good as I was ever going to get. Does this thing even work?” She stabs repeatedly at the Call button.

“Practice will take you a long way. Not the whole way. That was a painful thing to learn.”

“Not so hard, maybe.” I take the remote from her hand and gently press the Call button. This time there is a faint beep in the distance, at the nurse’s station down the hall.

School ended just after Memorial Day, thanks to a mild winter. In other years we’d made up snow days halfway through June. The final day of the term was celebrated with Field Day, an annual tradition: a picnic lunch, an outdoor talent show, all manner of highly structured fun on the lawn behind the school. When I think of it now, I’m struck by the great pains taken for our happiness and amusement, the poor teachers charged with policing our preteen horseplay—for them, a long and tedious day. Naturally we were ungrateful, the boys especially. Year after year we griped about the morning’s indignities—dodge ball, sack races, an endless series of inane games even girls could play. We clamored for a full day of baseball. It seemed the height of injustice that our bats and gloves were withheld until noon.

“Sorry, guys,” said Miss Seaver, teasing us a little. She was dressed for the occasion—thrillingly, to me—in jeans and a T-shirt, wooden clogs on her feet. “Everybody plays.”

In homeroom we were assigned teams for tug-of-war and the three-legged race. We were an odd number, because Tracy’s desk was empty. Miss Seaver seemed perplexed, frowning as she marked him absent. Nobody ever missed Field Day.

“Where is he?” Beth Leggett whispered to me.

“How should I know?” I’d left for school at the usual time and waited at the foot of his driveway, but Tracy had not appeared. “Home sick, I guess.”

My recollections of the day are generically pleasant—drawn, likely, from several Field Days and averaged into a single one. At three o’clock we were summoned into the shadowy building, to our respective homerooms, for the final dismissal. Like every year, it was a moment of high drama. Sunburned, breathless, joyously grass-stained, we waited for the bell. When it came we charged for the door, the whole throng of us bursting out of the school building into the sunlight. I remember a delirious sense of freedom, the muscular thrill of summer vacation upon me at last. Then, abruptly, a sharp confusion: a bunch of kids had congregated near the fence, staring at something in the faculty parking lot.

“What happened?” I asked—nonsensically, as though the scene required some interpretation.

A teacher’s car—I recognized it as Miss Seaver’s yellow Mustang—had been vandalized. Spray-painted across the driver’s side panel, in tall jagged capitals, was a word I’d heard only in whispers. I had never said it aloud, myself.

We stood gaping as Mr. Kovacs, one of our few male teachers, pushed his way through the crowd. Later I wondered who had summoned him, and how. How I myself would have articulated it: Somebody trashed Miss Seaver’s car. That, of course, didn’t begin to cover it. The word was the thing. Somebody had written that word.

“What’s all the commotion?” he said.

In my memory, there was a sudden silence as Miss Seaver came up behind him. Someone, apparently, had summoned her too.

“Ginny, don’t look,” said Mr. Kovacs, but of course she’d already seen it. Red-faced, her eyes filling, she turned away and walked back toward the school. You have to admire that. She was just twenty-three, a girl really. And yet some teacherly decorum (or maybe just her wooden clogs) kept her from running, which she must surely have wanted to do.

Ginny, don’t look. It startled me, then, to hear a teacher addressed by her first name. In the context of the day’s other, greater astonishments, it’s hard to believe I found this shocking, but I did.

“The police are coming,” Mr. Kovacs told us. “They’ll be here any minute, so get moving. We can’t have the whole eighth grade standing in their way.”

“You missed everything,” I said, breathless.

I was standing on Tracy’s front porch, a first. Normally I waited at the foot of the gravel driveway. That afternoon I couldn’t wait.

He looked unsurprised to see me. He pushed open the screen door and took a couple steps back—meaning, I guessed, that I was invited in.

The house was dark inside, the walls covered in scarred wood paneling. I barely noticed, caught up in the anticipation of what I was about to say. He led me into the kitchen, where something crunched beneath my feet. Tracy or someone had been eating peanuts. The floor was littered with their shells.

We sat at the kitchen table, gray Formica. Beneath my elbow was a crusty stain, mustard maybe. “You’ll never guess what happened.”

The condition of the house shocked me, though I tried to hide it. The stovetop was ominously blackened, as though it had seen a fire or two; the burners covered in yellowed tinfoil that looked worse than the stove. Near the refrigerator was an actual hole in the linoleum, the size of a man’s shoe.

“I bet I will,” Tracy said.

I stared at him a long moment, the realization dawning.

“Imagine her driving home in that thing,” Tracy said, and against my will I pictured it: Miss Seaver at the wheel of the yellow Mustang, the word CUNT big as life on the driver’s side door. “What a riot.”

A tiny smile pulled at his lips.

I can still recall the odor of the place. At that age I enjoyed the smell of other people’s houses, the exotic contrast with my own, which smelled of cleaning products and my mother’s cooking. Tracy’s house had a smell like nothing I’d encountered, cigarettes and wet dog and other things I couldn’t identify.

Outside a car idled loudly.

“You should go,” said Tracy. “That’s my dad.”

I followed him to the screen door. In the gravel driveway was the battered pickup truck I’d often seen there. Behind the wheel sat a skinny guy with an extravagant mustache, his face deeply tanned. He was younger than my own father and appeared to be dead asleep, though he’d been driving just a minute ago. This was as close as I would ever get to Tracy’s dad.

“Is he sleeping?” I whispered.

“Who cares,” Tracy said, opening the door.

“About the car. I won’t tell anyone.” I made the promise automatically—child enough, still, that not-telling was a point of honor. Only later did I realize he hadn’t asked me not to.

“I know,” he said.

That summer I distanced myself from Tracy. It was easy to do, without the daily walk to school. Once or twice, riding past his house in my parents’ van, I saw him pushing a lawnmower. I waved, and he waved back, and that was the extent of our communication.

I didn’t tell. More strikingly, I hadn’t even asked why he’d done it. I suppose I knew the reason, or thought I did: he did it because he hated her. Why he hated her was an entirely different question, one my young self would have been hesitant—embarrassed, somehow—to ask.

Now, probably, she is Mrs. Somebody, her maiden name retired like a star ballplayer’s number.

I never saw Miss Seaver again. Nobody did; she moved away from Bakerton and was not heard from. Now, probably, she is Mrs. Somebody, her maiden name retired like a star ballplayer’s number. Even today, with the whole world plugged into computer networks, women’s identities are more fluid than men’s. Slippery creatures, shape-shifters. If they wish to be, they are very easily lost.

She never drove that car again. The town cop, a man named Andy Carnicella, escorted her home that terrible afternoon. The yellow Mustang was repainted dark green and sold quickly—this according to Tara Sneed, whose father owned the used car lot in town.

In high school everything shifted. Fortunes rose, fortunes fell. I joined the track team and did respectably in the long-distance, a sport that demanded no special talent beyond an unusual tolerance for boredom. Beth Leggett continued her reign as prettiest girl, but Tracy Pasco was no longer of interest to her or anyone else. His eyes might have been crystal blue, but whatever handsomeness he’d possessed had been, in a single summer, dramatically ruined, in the form of truly disfiguring acne. At that age most of us had pimples, but Tracy’s were the worst I’d seen. From a distance—the only way I ever saw him—his face looked almost purple, and in spite of everything I felt sorry for him. Through a conspiracy of malevolent hormones, he had lost the attention of the Pantheon, which was surely worse than never having had it.

He ran with a rough crowd. At school they were largely invisible. I saw them mainly on the school bus, long-haired punks who monopolized the rear seats, silently spitting tobacco into cones of notebook paper. Dressed, always, in concert T-shirts: Iron Maiden, Black Sabbath, bands I rejected unequivocally. It seems a foolish distinction now, but their taste in music was, at the time, enough to make Tracy and his friends irrelevant.

I would have put him out of my mind entirely, if not for my sister. One afternoon during my junior year, I’d boarded the team bus—we were about to leave for an after-school track meet—and glanced out the window to see Tracy and Nina walking together through the deserted school corridor. (Bakerton High’s only notable architectural feature was a bank of large windows along the west side of the building.) This was so utterly impossible that I blamed my vision, the blinding glare of the afternoon sun.

Then, a week later, I saw them again.

“I like him,” Nina said when I grilled her about it. “He’s a very talented artist. Not that you would care about that.”

She was right; I didn’t. “He’s a creep. I’d stay away if I were you.”

“Since when do you care who I talk to?” She looked genuinely puzzled. “Anyway, I thought you guys were friends.”

“He’s not my friend,” I said.

“I never even knew him,” Nina claims now. “Certainly we never dated.”

I question her memory, but not her honesty. She truly believes everything she says. Their one date, to a Sadie Hawkins dance, ended badly, with Tracy driving his dad’s truck into a telephone pole. Tracy was unhurt, but Nina came home bruised and bleeding. She was forbidden ever to get into a car with him again, and dutiful daughter that she was, she readily agreed.

After high school I went on to the state university. Like a number of our classmates, Tracy joined the Navy—with the mines no longer hiring, there was nothing left in town for them to do. I didn’t see him for many years, though he crossed my mind occasionally—uneasily, like a shameful secret from my past.

My performance at the state university was, I will admit, less than stellar. After many false starts, I settled on a business major and left, with no diploma, after five years. Due to a series of misadventures I won’t go into, I found myself living, at age thirty-four, above my parents’ garage, in the in-law apartment Gram had inhabited until she died. I paid utilities but no actual rent, an arrangement my parents agreed to when I promised to make double payments on my student loan. A job of any kind was by then a rare commodity in town, and I felt lucky to be driving a truck for Anheuser-Busch, delivering kegs and cases to the local bars.

Late one summer afternoon, I’d just finished my last delivery—the Commercial Hotel—when a guy at the bar called my name.

“Hey. Patterson.”

It took me a moment to place him. His hairline had receded, and what was left had been buzzed short. His skin had cleared up and he looked very fit, nearly muscle-bound, as though he spent considerable time in the gym. If not for the crooked eyetooth I might not have recognized him. He looked older than I did, or was, or felt.

“Tracy,” I said. “How’ve you been?”

He took cigarettes from his pocket and mouthed one from the pack. “I’m surprised to see you back here.”

“I live here. You know, for now.”

“Let me buy you a beer. My dad died.” Tracy lit up, waving out the match as though it annoyed him. “I came to clear out the house.”

“I’m sorry.”

“It was a couple months ago,” he said, as though this negated any possibility of grief.

We drank, and Tracy told me about his life. In the service he’d trained as an electrician, a trade he still practiced sporadically. With his Navy pension—he had fifteen years—he could afford to work only when he felt like it. That he’d never married did not surprise me. He owned a little house in western Montana—a shack, he called it—on twenty acres. He’d driven east, I-90 to I-80, over two weeks’ time, stopping here and there in towns along the way: Gillette, Wyoming; Sioux Falls, South Dakota. I’m almost certain he mentioned those places by name. To me they sounded magical, a part of the world I had never seen.

Glad for someone to drink with, I lingered longer than I should have. We were on our third or fourth beer when the two women came into the bar, a blonde and a redhead. Tracy’s eyes followed them avidly. “Holy shit, is that Beth Leggett?”

“Beth Vance now, but yeah.”

“I almost didn’t recognize her.” Tracy studied her openly. She was still beautiful, though after three kids no longer quite so shapely. “She got married?”

“And divorced,” I said.

She hadn’t recognized Tracy; she’d simply been drawn to him. In that moment I understood the basic facts: Tracy was handsome and Beth was single. It was junior high all over again.

A moment later Beth spotted us. “Nathan!” She charged across the bar in our direction, smiling brightly. Her enthusiasm was puzzling, given that I saw her every Friday afternoon at Saxon Savings, where she’d worked since high school.

“Back in a minute,” Tracy mumbled. “I need to make a phone call.”

Beth approached looking crestfallen. “Where did your friend go?”

She hadn’t recognized Tracy; she’d simply been drawn to him. In that moment I understood the basic facts: Tracy was handsome and Beth was single. It was junior high all over again.

“He had to make a phone call.”

She glanced uncertainly at her red-haired friend, waiting at the other end of the bar. “We’re going to have dinner, but maybe we can all have a drink afterward?”

“Sure,” I said.

I watched her follow the other woman into the dining room. A moment later Tracy reappeared.

“I can’t believe that’s her,” he said.

“In the flesh. She wants to have a drink with us later.” I drained my glass. “The Pantheon. That’s what I used to call them, Beth and Tara and Melissa. Wyman, remember? She’s married now. She was home at Christmas for a visit.”

“How’d she look?”

“Good,” I said.

“How’s your sister?”

I felt a sudden chill.

“She’s fine.” There was much more to say, but I wasn’t about to say it. At art school Nina had excelled globally, until she hadn’t. Her recent history was a family matter, something we didn’t discuss with strangers. My parents, when asked about her, still bragged shamelessly, their pride in her a habit they couldn’t break.

Tracy smiled, hiding his crooked tooth. “I always thought you scared her off me.”

I should have excused myself then, and almost did. The lie—I have an early morning tomorrow—was ready on my lips.

Instead a remarkable thing happened. Tracy touched his index finger to his nostril.

“Wanna get high?” he said.

At this point in the story an explanation is in order. My drug use, at that time, was the defining feature of my life. It wasn’t the only reason for my lackluster academic career, my spotty work history, my strained relations with my parents; but it was the dominant one. Somehow Tracy had divined this, or maybe he hadn’t. Maybe he’d have asked the same question of anyone he drank with, as I would have in those days. A couple of drinks always made me crave.

Wanna get high?

Today, some years sober, I can admit that those three words roused me—still do—like a defibrillator, an intoxicating jolt to the heart.

I followed Tracy into the parking lot, to a Dodge Ram pickup with Montana plates. We rode in silence out Number Twelve Road, the rusting skeleton of the old Twelve barely visible in the twilight. Without asking I took one of his cigarettes.

“I thought you didn’t smoke,” Tracy said.

At Garman Lake he pulled off the road and parked. From the glove box he took a compact disc—Deep Purple, Stormbringer. His musical taste, apparently, hadn’t evolved since high school.

“The bitch got fat,” he said.

It took me a moment to understand what he was talking about. I didn’t see how such a thing was possible, and yet for a horrible moment I thought he meant Nina.

“Beth Leggett. I always knew she would.” He cut two slender lines with a credit card and took a powerful snort. “I used to think about how I’d do her. A tire iron, I thought, but now she’s too fat to feel it. A sledgehammer, maybe.” He bent over the CD case and inhaled mightily. “I’d save the tire iron for Melissa Wyman. A tire iron right upside the head.”

I lit a fresh cigarette with the last one, aware of my hand shaking. A fire whistle blew in the distance. I leaned over the CD case and inhaled.

“Come on, Patterson! Tell me you never thought about it.”

“I never did,” I said.

I live in Virginia now, the DC suburbs. After rehab I went back to school—not college but something more in line with my abilities—and in the space of a year learned to write computer code, got hired at a software company and married a woman, also sober, who is the love of my life. Though my relationship with my parents remains tense, I go back to Bakerton every month or two, to visit Nina. She is able, mainly, to live on her own, in the garage apartment I used to inhabit. If she’s feeling well, we might spend a pleasant evening at her kitchen table drinking peppermint tea and reminiscing about the past.

She has no memory of the night she came home bruised and bleeding. A car accident, she said, and everyone believed her, because back then Nina always told the truth.

Her breakdown had nothing to do with Tracy Pasco, nothing much even to do with her failure as an artist. Her symptoms came on gradually her final year in art school, the usual age of onset, though it took a couple of years to identify their cause. She is lucky, as schizophrenics go, in that her delusions are largely controlled by medication, though the drugs have left her foggy, lethargic and obese. Her memory, as I have said, is unreliable, and the weight gain is demoralizing. Periodically she becomes so disgusted that she stops taking her medication, with predictable results.

She is no symbol of lost promise, no symbol of anything, and yet seeing her reminds me of a particular time in our lives when potential seemed to be everywhere.

She is my earliest friend, keeper of my secrets—witness to my early failures and shames, and a few of the recent ones. She is no symbol of lost promise, no symbol of anything, and yet seeing her reminds me of a particular time in our lives when potential seemed to be everywhere: in every art class a budding Picasso, a young Katharine Hepburn in every cringe-inducing school play. These prodigies—Nina was one of them—are unfairly blessed and cursed. The lucky ones will disappear into ordinary lives, doting mothers and proud fathers, coaches and teachers paid to nurture the next generation’s false hope. This is no middle class affectation; Bakerton—once solidly working class and now unworking, a town industry has abandoned—runs on the same illusion. It is a generous fiction like the Tooth Fairy or Santa Claus, an elaborate ruse in which whole communities are complicit, fueled by wishfulness and misguided love.

I won’t tell, I said, and for a long time I didn’t.

Sober now, I follow the news reports. I will never know if Tracy has done the things he’s accused of. (The nurse in Gillette, strangled with her stockings; the kindergarten teacher in Sioux Falls, beaten with a blunt object. A tire iron, the authorities believe, though the weapon was never found.) Tracy has never been convicted of anything. A grand jury refused even to indict him. He is a free man.

Gillette, Wyoming. Sioux Falls, South Dakota. He mentioned those places by name, as though he wanted me to know.

The night at Garman Lake ended uneventfully. Tracy drove me back to my apartment above the garage, where I lay awake for many hours with a pounding heart. The next morning—bleary, exhausted—I drove straight to Wellways, nearly three hundred miles. This time I stayed the full thirty days—and, in Group, finally broke my promise to Tracy.

I told.

His drawing of Miss Seaver, his attack on her yellow Mustang: out of shame or fear or some reflexive, senseless loyalty, I’d carried these secrets for more than twenty years. Confessing was a profound relief, a crucial step in my recovery; but it was essentially a selfish act. Had I come clean back in 1980, to a parent or teacher, Tracy might have been rescued, given the help he needed (though in Bakerton, then or now, it’s hard to imagine that happening, as several in Group pointed out.) At minimum he’d have been identified; he’d have a record somewhere. Someone—the omnipotent authorities, the people who protect us—would be watching him. Or so I would like to believe.

What he did or didn’t do to Nina. Another truth I will never know.

Garman Lake has become, for me, a haunted place. I realize this is irrational. Beth Leggett, Melissa Wyman, Robin Godfrey, Tara Sneed: each of these women is still very much alive.

Tracy Pasco lives two thousand miles away, in a secluded shack in western Montana. In my dreams I see him driving, stopping here and there in towns along the way.