I first met Sabine Heinlein in a ceramics studio on the Lower East Side. There were ten of us sharing a modest basement space at The Manny Cantor Art Center of the Educational Alliance. Heinlein and I were working at opposite sides of the same table. Our tasks that day were very different. She was carefully painting a whimsical crocodile on a ceramic platter and I was smacking my clay onto the table for a handbuilding project.

When I stopped she looked up, seemingly with gratitude. Later, she handed me a business card announcing her dual identities: quilter and writer. On the front was a photo of her Fly Pillow, the insect’s bulging red eyes and pale wings rendered in tiny stitches; on the back was a photo of her Mandrill quilt, the playful, colorful, primate posing against a background of bright green grass.

Heinlein turned to quilting three years ago, shifting from a remarkable career as an investigative journalist that took her from Baiersdorf, Germany, a very conservative community in Bavaria and a place she calls “the Texas of Germany,” to New York City. She grew up in an upper-middle-class family, the youngest of three daughters, and was supposed to take over her father’s real estate business. Very early on, though, she realized it was not her calling and fled to Hamburg, enrolling in Hamburg University and earning a master’s in art history. Although she never really made art as a child and confessed to me that the sewing machine in her house “was always broken,” her mother did take her to museums, and she was always told that she was good with her eyes. “I was not good at drawing,” she said. “I was the one who was good with language.” But, Heinlein reminded me, “Being good at art can mean many things. You do not necessarily have to be good at naturalistic representation. You can be good at fabric.”

Heinlein wanted to become a novelist but she had no idea how to go about it. She turned to journalism instead, and began to write long articles on art and culture for German newspapers. Still, she did not feel at home in the world of German journalism. “There was no ‘‘I and it was very objective,” Heinlein said. “It was not playful and it did not employ literary tools.”

When she moved to New York City in 2000, she set as her mission mastering English. Every morning she sat down with a newspaper and a dictionary and discovered that she loved the language. “German is so incredibly precise,” Heinlein said. “English felt like liberation. There is all this play in it. You can just make up words.” Beyond the differences in language was the difference in attitude. “In Germany, if you are a cobbler, you stick to shoes,” she said.

Heinlein discovered several literary American journalists whose work she admired—Joseph Mitchell, Susan Sheehan, Janet Malcolm, and Adrian Nicole LeBlanc—and slowly an image emerged about who she wanted to be as a writer. She enrolled in the literary reporting master’s program at New York University, which, although very supportive, still felt a little narrow. “Perhaps this feeling foreshadowed my current career as an artist. I always hung out with the artists. I felt more affiliation with them. My two husbands were both artists and my boyfriend before that was one, too.”

Over the next decade, Heinlein turned her attention to people on the margins, folks whose stories were rarely told. Heinlein’s portfolio grew bolder culminating in her 2013 work of narrative nonfiction, Among Murderers: Life After Prison, Heinlein shadowed three former convicts, Adam, Angel, and Bruce, for more than two years. Her narrative traced their journey from “prison to freedom.”

Despite her success, she found herself getting increasingly anxious about the kind of things that you have to do as a journalist. “My skin was too thin to constantly knock on doors,” she said. “How do you call up a father accused of abusing a son?”

Donald Trump’s election proved a turning point in her career. “Things in journalism seemed to get worse and worse and people kept harassing me and calling me a fake journalist. I hate to say that was one of the reasons why I gave up but it was just awful.”

Heinlein had written a piece on animal hoarders, but found that she did not enjoy writing about animal abuse. She did, however, feel a great affinity with animals. Heinlein grew up in a house full of rescues. “We had dogs and we had cats. We had ducks that we rescued in floods. Each child had two ducks of our own. We even rescued mice from cats.”

After writing a profile of modernist quilter Laura Preston, Heinlein put down her pen, picked up her needle, and began stitching her first quilt. Inspired by Josef Albers’ squares, which she admired but found “really boring,” she added a flamingo to the quilt, in an effort to reflect her own quirky vision. This was the turning point.

Given Heinlein’s tendency toward introspection, the benign matter of animal quilts soon became more complex, its content more serious. Heinlein started reading books about the global depletion of wildlife. “People just have no empathy for animals,” she said. Her first animal quilt, 95 inches square, depicted elephants with a bunch of human skulls in the middle. “I just reversed the story,” she said. Soon after, she made a quilt about roaches, using men’s shirting material as her fabric of choice. “I like the juxtaposition of white collar material with quilting, which is so often dismissed as an idle women’s pastime. Quilting is a traditional medium that has never really been taken seriously in the art world,” she said.

It takes Heinlein six weeks or more to hand-stitch her quilts. They’re made of three layers, with a fourth consisting of the animals appliqued on top. The work, Heinlein said, “ is very rewarding, maybe because it gives me permission to sit still.” That, she confessed, is not an easy task for her.

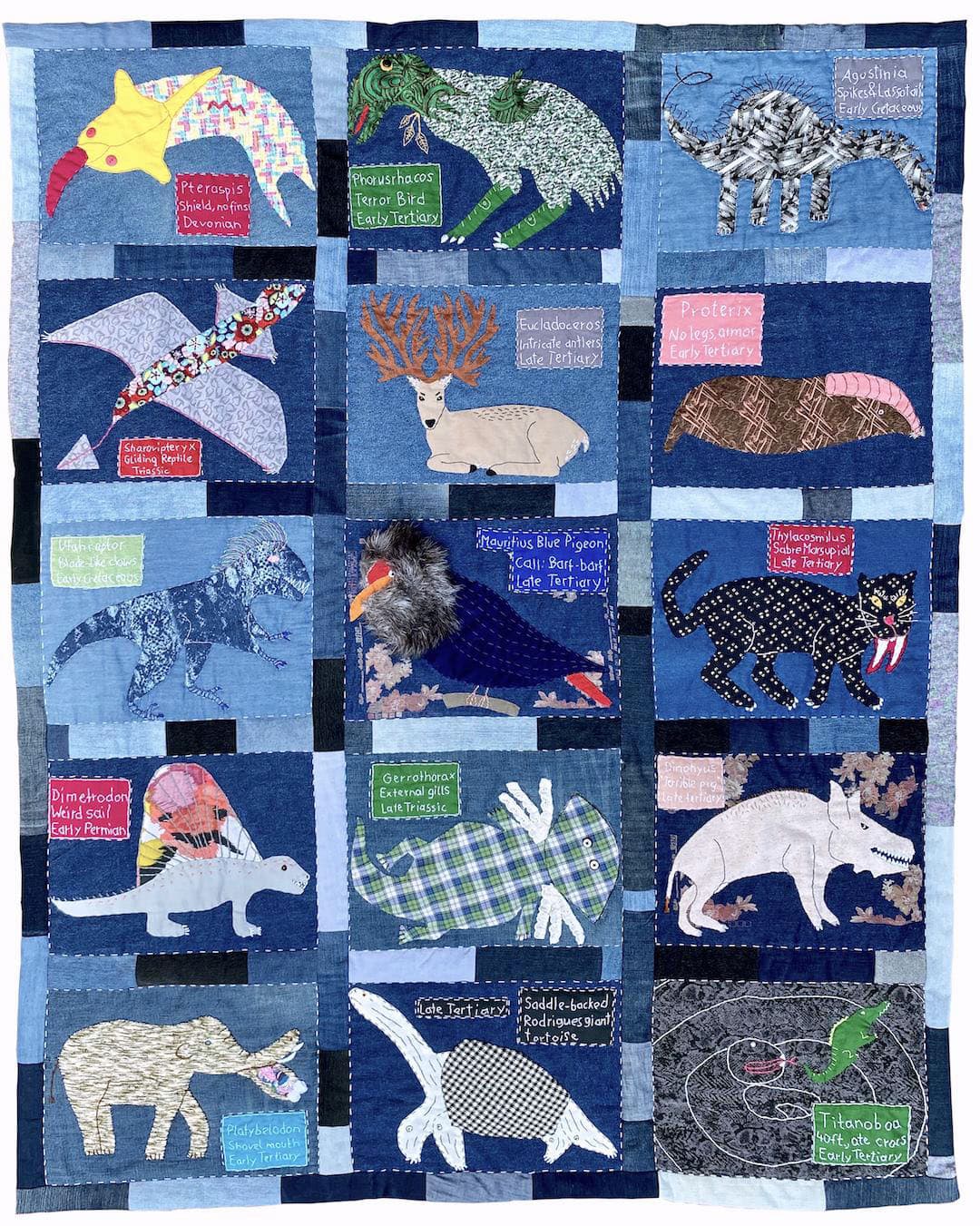

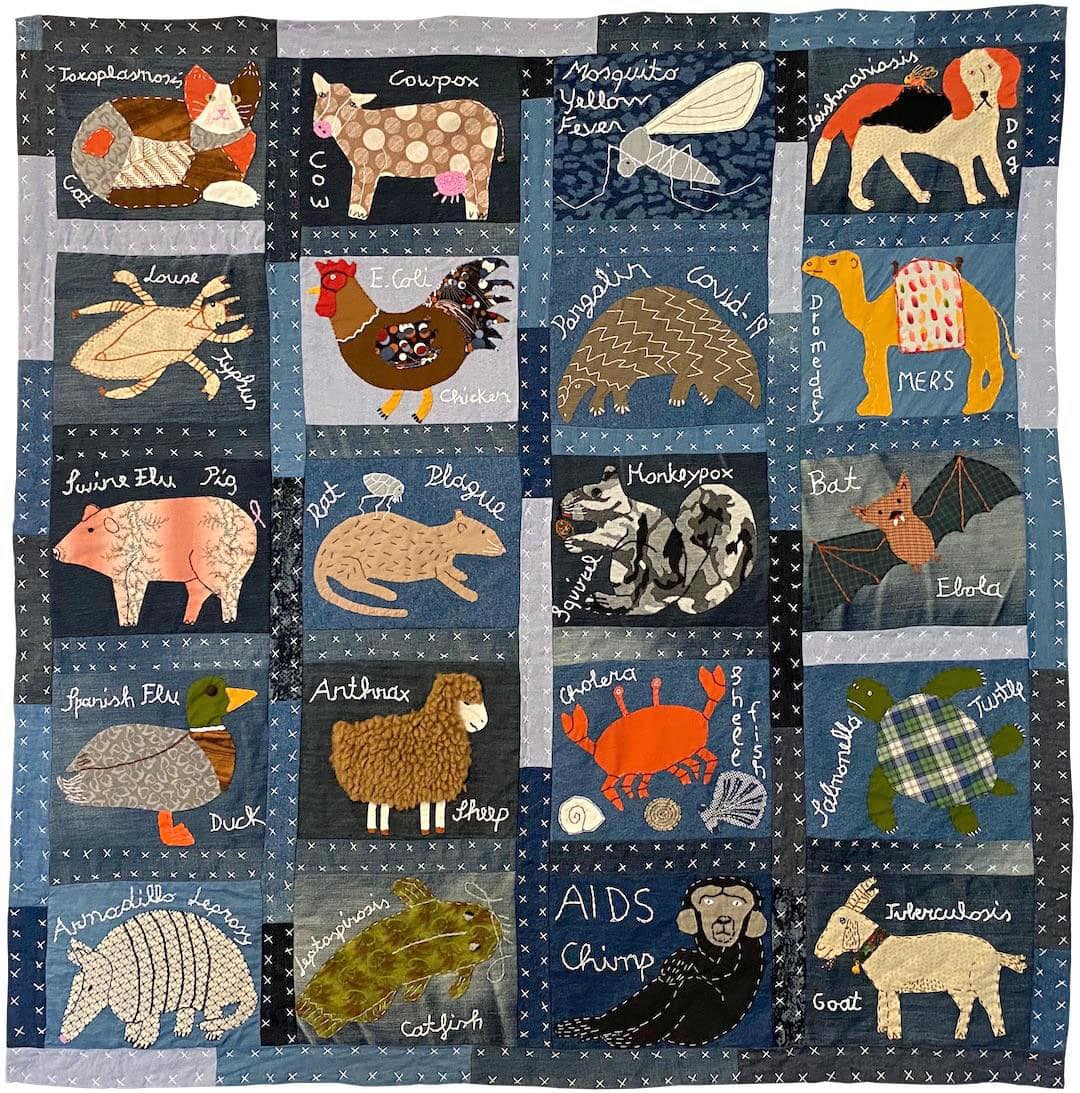

In March 2020, Heinlein was scheduled for reconstructive ankle surgery. She realized that she could not wrestle with large pieces of fabric while on bed rest recovering, and decided to work on smaller pieces that could then be stitched together. Her original plan was to make an extinct animal quilt to highlight animal suffering and man’s contribution to it. But when COVID-19 struck, Heinlein began reading books on infectious and zoonotic diseases, diseases caused by germs that spread between animals and people. She learned that two-thirds of all infectious diseases are zoonotic. “Experts have been saying that there is going to be a big pandemic for years,” she said, “and nobody listened to them. Nobody seems to care. Nobody wants to look into the future: global warming; mosquito-borne diseases; and deforestation.”

So was born her zoonotic disease quilt, a striking 45-inch-square work that Heinlein finished in April 2020, at the height of the pandemic’s first wave in New York City. By stitching together twenty panels of sweet (and benign-looking) animals, Heinlein’s creation seems to bring humor to a serious subject. She describes the animals with affection: “a lovely cow” represents cowpox, “a funny-looking bat, “ Ebola, a “wooly sheep,” anthrax, and so on.

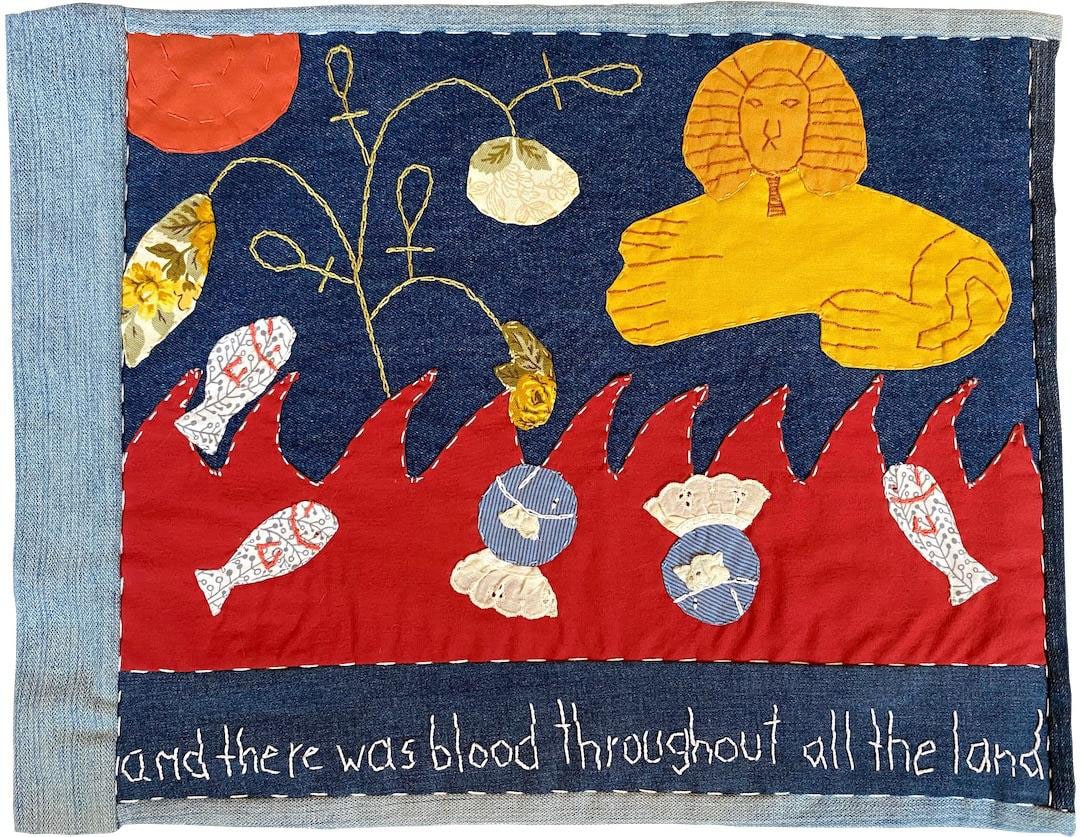

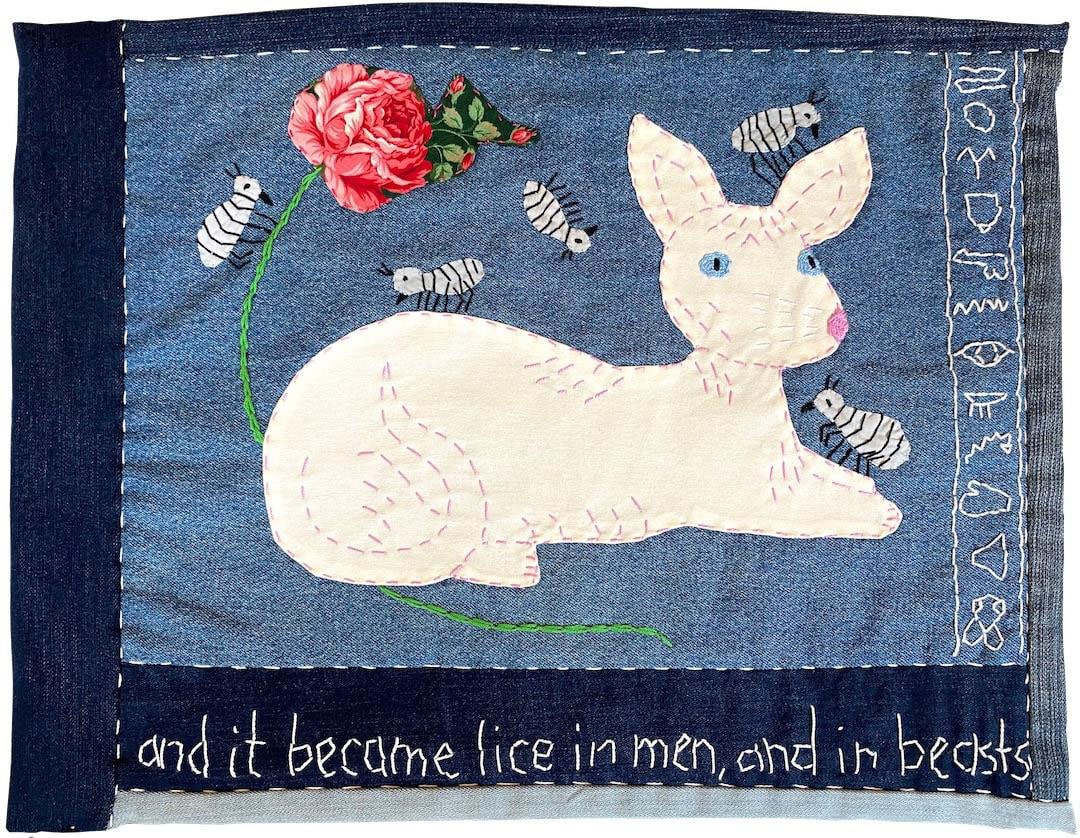

A more recent creation gives us her embroidered interpretation of the ten plagues described in Exodus. “They are in the DNA of western culture,” she said. Although she was baptized Protestant, Heinlein describes herself as an atheist. Her research took her deep into religious and scientific theories about the ten plagues. Her first thought was to make a hanging quilt with all of the ten panels attached to one another, but when she laid them out, the writer/quilter realized that it should be a book.

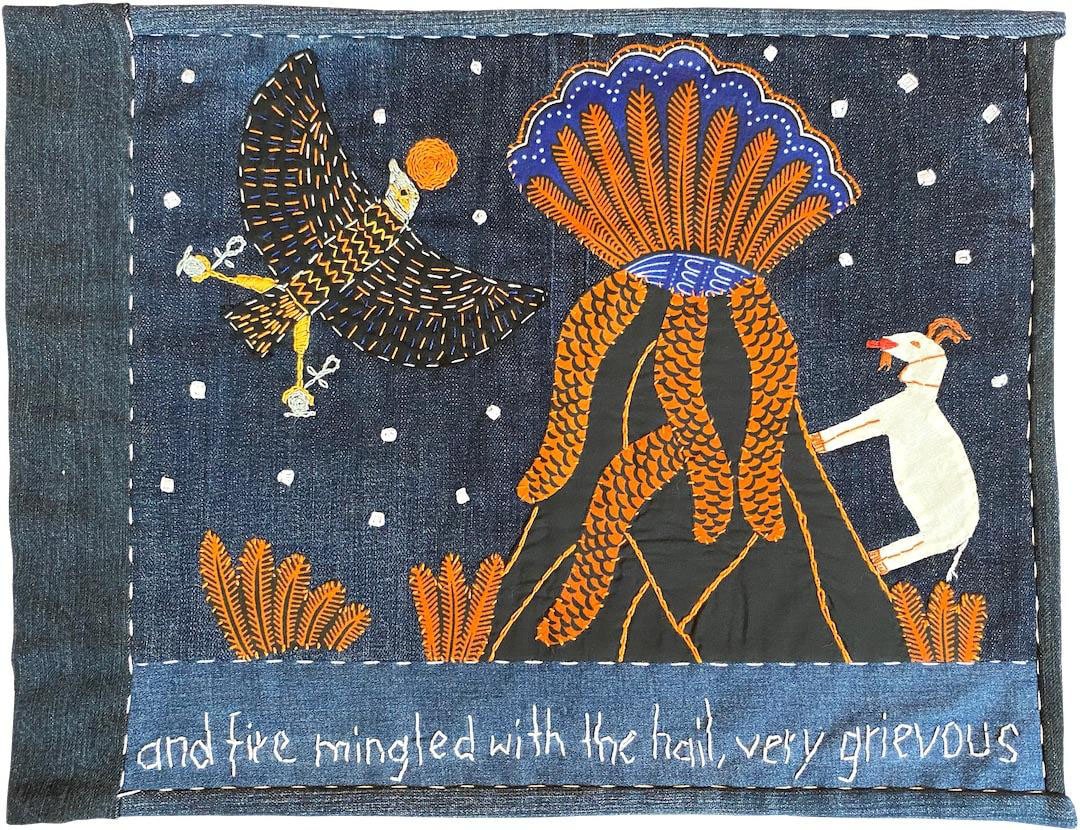

On each page, below a passage from Exodus, like Rabbinical commentary, Heinlein provides the reader with notes on her quilts, often describing materials used and emotions conveyed: In Blood, the panel is made from red fabric and denim scraps, and “a red sun shines down on a chubby sphinx and a sad plant with drooping leaves and flowers.” Heinlein shapes several of the plant’s branches like the Egyptian ankh, which represents life and death. In Hail and Fire, Heinlein stitches a fire-spitting volcano, mid-eruption. In the Frogs panel, frogs with green arrows (she found the vintage fabric at Goodwill) are jumping into her kneading bowl and her bed. We learn, in her accompanying text, that “the raining of flightless animals has been reported throughout history.”

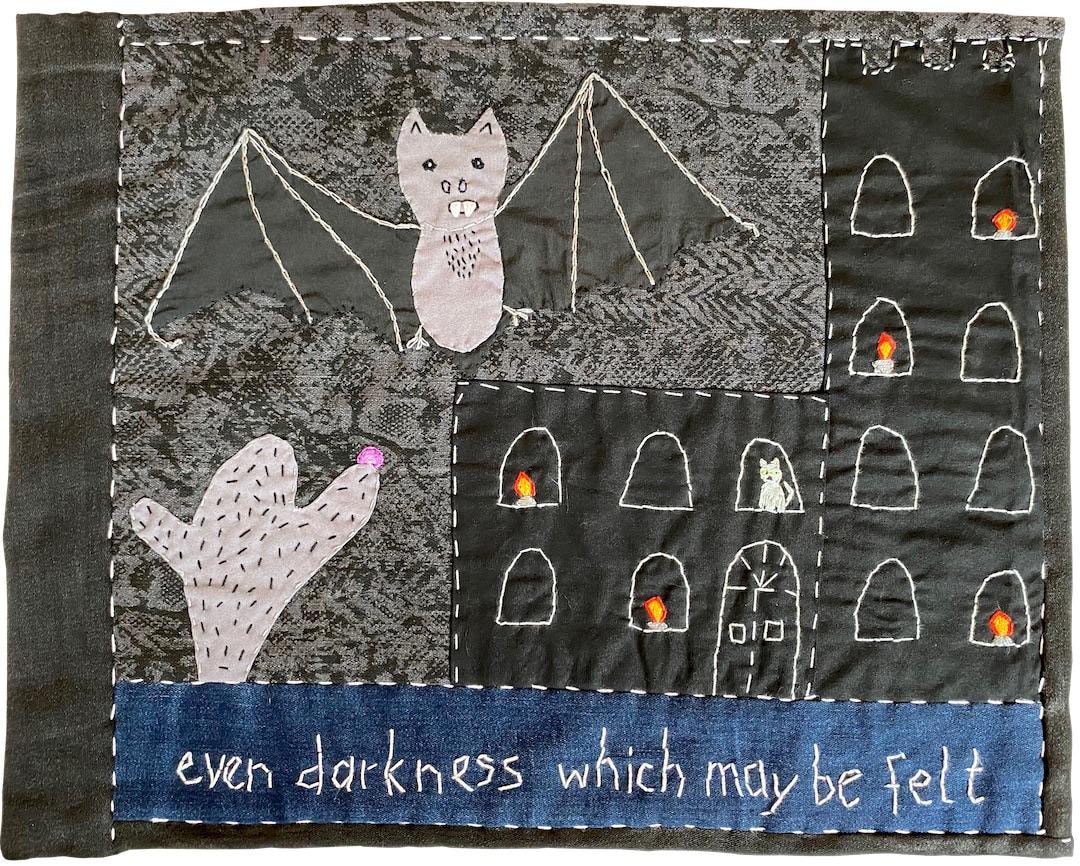

To make sure that we can see the tiny creatures, Heinlein places the lice in one panel on an Egyptian hairless cat. Around the margins, she has stitched hieroglyphs. For Boils, Heinlein chose to stitch them on camels, animals that she loves because they have “the softest snout and make the most peculiar sounds.” In Darkness, Heinlein selected bats, because she has “an obsession with these creepy creatures. Few animals are more mysterious and transmit more disease to humans than bats,” she said. “The viruses that cause Ebola, rabies, SARS, Nipah, Marburg, and Hendra have all been traced back to bats.”

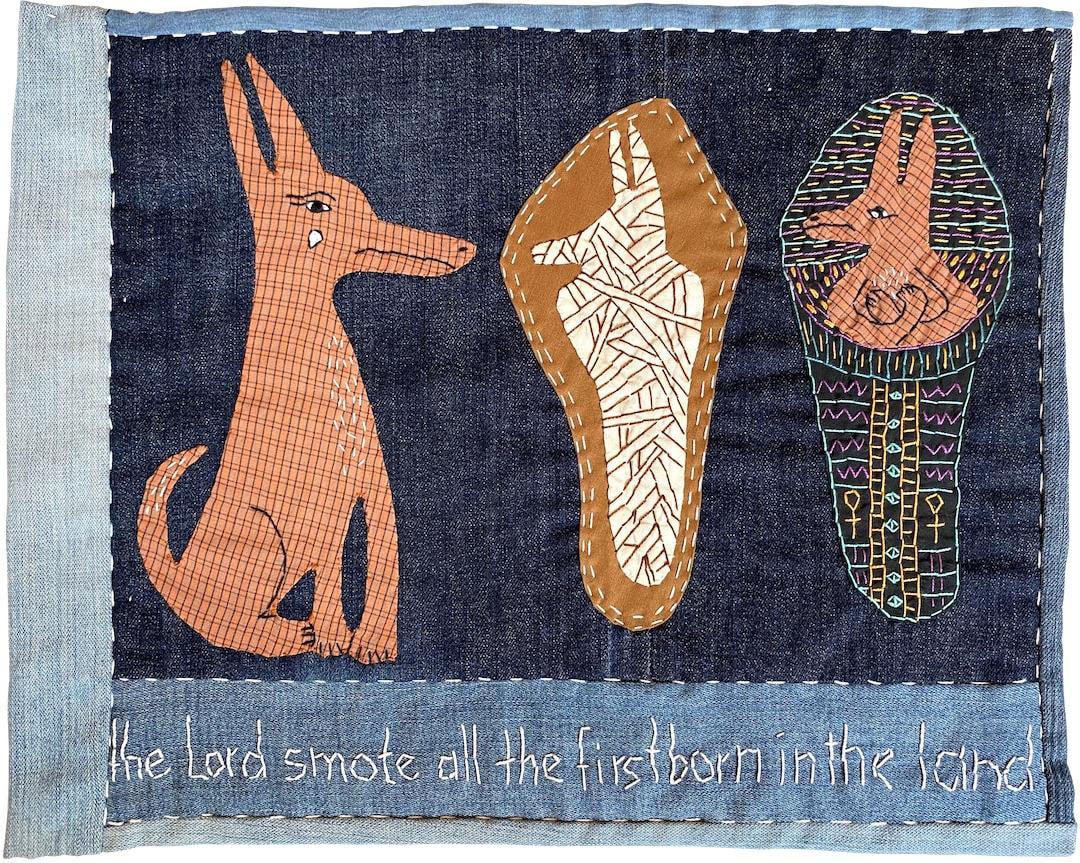

For the tenth plague, Death of the Firstborn, Heinlein stitched a grieving mother dog and her firstborn puppy instead of a human. The dog in the panel resembles the jackal god Anubis, whose appearance Heinlein says was inspired by the Egyptian wolf—a species now on the endangered list.

Journalistic writing required Heinlein to be precise, but, inspired by Gee’s Bend quilters in rural Alabama, and by Harriet Powers, a Black quilter from the late 19th century, Heinlein feels the freedom to be imperfect when stitching her quilts. One stitch follows another. There is no need to call up an expert on the telephone.