Content warning: This piece discusses suicide; if you or someone you know is considering suicide, please visit the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline for resources and support.

You can’t start with the thing. You have to start with something other than the thing. Like a stone entering water (the water closing up after it).

On January 8, 1988, my uncle Steven hangs himself with a length of rope in the basement of his home.

I am three years old. My cousin Maggie, his daughter, is two.

Afterward, I ask my mom only one question: Would you ever do that?

She says to me, from the future, that I must have been satisfied enough with her answer because I didn’t ask again.

In the cartoon Steven Universe, Steven (last name Universe) is descended from a long line of gem-based aliens with magical superpowers.

Each gem has, and embodies, a weapon: Pearl — tall, thin, and dutiful — carries a spear; Garnet, powerful and with a sense for the comic, has giant boxing-glove hands; Amethyst, playful and sharp, wields a whip.

Steven, whose gem is rose quartz, manifests a shield.

I do not know what my weapon is, at the moment. I walk down the sidewalk listening to music. I am often afraid that I will hurt the ones I love, and I take my tall man-body and shrink it down a little way smaller — not all the way, but enough so I can feel it.

Visualize the way that trauma has shaped your people, over generations; then visualize that forming a kind of collective spatio-temporal-topographic mold. Pour the metal in and let it cool.

What weapon emerges?

I do not think my people carried a rope. I wish I could know my uncle; my cousin, his daughter, has an old bike of his, and I imagine peddling very fast along an open road with the wind flying by and think that that is a weapon.

If grief were a weapon, what shape would it take?

My mom has a framed picture of Steven holding a dog in his arms. He is young and has bushy hair on his head, none on his face or arms yet.

Steven Universe has a creature named Lion who is a pink lion with a lush pink mane that, we eventually find out, helps Steven cross dimensions.

Lion is obviously magical. Not quite a pet, he and Steven appear to choose each other. Why is Lion around?

There are few men in the show, and no toxic men, both of which make it notable. There is Greg, a fumbly musician and Steven’s dad, though the gems take on most of the parenting duties. Lars, an angsty teen, has trouble with his feelings.

For Lars, Steven represents both the threat and the promise of what it could look like to be vulnerable, silly, caring.

For Steven, Lars represents a curious window into what he might become were he not, always and forever, a preteen boy. Unlike Lars, he is not and can never become threatening.

There is safety in that; there is also, in a certain sense, the absence of a future.

I won’t ruin it for you, but in Lars’s trajectory, his curly mohawk, his plugs…must change color.

Something I often hear: “Suicide is a wish for transformation.”

What would it look like, for white masculinity to

change? Would it have to die first?

Who has the touch that could resurrect it?

In the movie A Star Is Born, Bradley Cooper’s masculinity can only end in suicide. Healing is outside the window of what is possible for men.

I am tired. My body is tired in its stupid comfy airplane armchair.

WHY IS THAT THE ONLY ENDING AVAILABLE FOR BRADLEY COOPER??????!!!!??

I am unreasonably angry when he shuts the door to his old garage after putting his dog outside. Have the courage to face the possibility of your healing!! At least leave your dog in there with you!!

It reminds me of the thing that that famous leftist philosopher says about capitalism and science fiction: it is easier to imagine apocalypse, our own end as a species, than to imagine a change in economic and political systems that would make other ways of being possible.

So, it’s easier for men to imagine suicide than healing. (It’s easier to imagine suicide for men than healing.)

It makes sense why white masculinity would be having so much trouble in this moment.

There was another shooting in Texas today. Some guy stole a mail truck.

I think about the difference between choosing to kill yourself and choosing to kill a bunch of other people. And how my uncle Steven, even though he was very unhappy and in a lot of pain, at least did not kill a bunch of other people.

I almost wrote “male truck,” that he stole a male truck.

Straight Pride was yesterday in Boston. So many angry white men!

I don’t really feel anything about it; in the pictures the people out there look like extras in a movie, with their red bandannas and American flags. And the ones on our side, it pains me to admit, also take on the look of extras. Everyone dressed up for the movie’s casting call.

There aren’t mass shootings in Steven Universe. Humans do mean things, like hurt each other or not tell the whole truth, but they usually feel bad and apologize by the end of each eleven-minute episode.

The only existential threat humans face is from some of the bigger gems, who, like all truly committed colonizers, want to wipe out life on their target because it’s in the way of mining for precious materials that will help them expand further. It’s not personal. The gems, even the evil ones, are above mass shootings.

I guess, as the show goes on, it becomes clear there are no evil gems, only gems who are in a lot of pain.

Steven Universe’s tears are healing. They fall on a broken leg and it mends; a crack in a portal and it fuses back together.

I like how the word tears is both “tears” and “tears,” and I strive to reuse that fact a lot in my writing.

My uncle Steven probably had tears. I don’t know if he developed uses for them. David Berman (d. 2019, suicide) cried little songs that weren’t all that teary, more numb, but in them you sensed an intelligence and perceptiveness and humor that could sometimes awe you. He’s not in this essay, though, because his name’s not Steven. Scott Hutchison (d. 2018, suicide), also not named Steven, foreshadowed his exact method of suicide ten years earlier, in a song, which is real commitment.

And fully clothed, I float away

(I’ll float away)

Down the Forth, into the sea

I think I’ll save suicide for another day

I didn’t know he was dead now until I heard David Berman was dead, and now they are both dead.

All my favorite singers have been doing this, apparently. I feel affronted.

Of the 23,768 reasons Steven Universe is brilliant, reason #2.5 is that it’s a freaking musical. There is singing and songs, and the characters explore their feelings through the singing and the songs.

Nathan, on the Sarah, Sara, and Sarah podcast, says it’s homophobic to dislike musicals, with which I agree; it’s why I used to think I disliked them.

I am sure, suddenly, that if my favorite singers made even one musical, they would have survived all this.

I think, for every man who is ready to kill a whole bunch of people, if we could just prescribe musicals, we would probably save a lot of lives.

First they would have to listen to some really depressing music, though, like The Mountain Goats’ No Children.

I am drowning

There is no sign of land

You are coming down with me

Hand in unlovable hand

And I hope you die

I hope we both die

The move in that song from I hope you die to I hope we both die is, in essence, what we’re going for: to usher someone, ever so gently, from murder (outward projection) toward suicide (inward projection).

To move them from suicide to life, then, we can prescribe musicals. Musicals create the conditions for acceptance. Here are all your feelings: feel them! All of you are welcome!

There’s a treatment arc here. It’s just science.

Okay, so all of these white men (musicians) keep killing themselves, and all of these other white men (people who hate women and Black people?) keep killing other people. Meanwhile, Toni Morrison (Black woman, writer) dies after a long, fruitful life, and all the pictures in the paper are of her dancing.

For a long time I thought the treatment for my white man-ness was to become more rigidly not-bad, something like the opposite of dancing.

When you begin to wake up to your very real pain, and realize that you are inside a world where there is even greater pain, and that other people are in a lot of pain;

but you can’t wake up to that world’s pain or other people’s pain because you feel they are in competition with your pain, because you are used to your pain being yours alone and so lonely, because you have been taught to be alone with your pain; and it becomes increasingly hard to feel any of the pain, either yours or the world’s or another person’s;

and, because your pain continues unseen, unheld, untouched, you become angry at those other people who are also in pain, who have had that pain seen or held or touched; because that touch to you feels so scarce; and you are so very angry and filled with despair that that kind of touch now feels impossible —

that is when white men start killing people.

When we say kill yourself in online forums, we are projecting our own secret desires.

We are testing the waters on another [virtual] body.

When my partner reads this essay, she informs me that there are some issues with pronouns. You sometimes use you to mean you (a general other); sometimes I; sometimes you, the reader.

Maybe I am struggling with where my we is. I am different from them; I am one of us. I am with you.

I want to live until I’m real, real old and die at home or in a hospital in front of my kids, for whom it is an inconvenience.

I want to live longer than a centipede is long, longer than the migration patterns of birds confused by human development, longer than this sentence.

I want you (us) to get better.

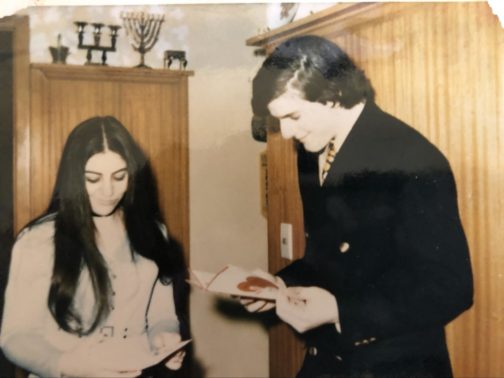

In this photo (the one where he looks most like me), my uncle is leaning over a Valentine’s card, in profile, next to Sharon Levy, who, tongue planted firmly in her cheek, is also reading one. The viewer can only assume that the valentines are from each other, and that Steven has written something decidedly not serious.

Two menorahs are above them, in the top left of the photo. Sharon, following tradition, wants to be with Steven forever — she must be the most beautiful woman in the world, I think, at that moment — whereas Steven follows, as usual, the script of his own little comedy. They are deft moves; they keep the feeling at bay.

I recognize these moves from his other letters.

In another photo with Roscoe, his dog, he seems to be almost hiding. This joy is a shield.

Because I never knew my uncle, the few photos I have fill up with meaning. Along with a few anecdotes, they begin to pool into a story.

And someday I will be a story for someone, I think.

Not because I am thinking of suicide! But because I will die, and I will leave fragments behind.

The way he chose to leave

leaks into the pictures with which we are left

which are pictures, also

of the way he chose to live.

It may be pathetic to break out into poetry — so transparent an attempt to induce pathos! — and yet to avoid it, for fear of that, may be equally cowardly. Writer’s choice.

Similarly, to write about Steven in connection with these other themes risks erasing his very real existence. Yet to not write about them?

Lars turns pink.

I know, it’s a spoiler. But it means he is healed, in his lifetime, and I think maybe you needed that at this point in the essay. When he dies, in maybe the first truly selfless act of his life, he is resurrected by Steven’s touch. No humans have died in the show yet, so the writers make you feel this moment.

I bring this up because I think maybe I am trying to bring my uncle back, in these tiny paragraphs. I am trying to touch him, to turn these old photos pink.

I am thinking of what it would be like to sit shiva for my uncle, thirty-plus years after he committed suicide. Shiva itself a practice lost, to my family, over time.

What would it look like to sit with my mom, my cousin (his daughter, who was two), her mom?

When you are that overwhelmed by grief, do you even get a chance to mourn? To honor the person?

My mom shares with me today that she had her doctor prescribe her Xanax two days after the suicide.

Her friend Elaine soon told her to get off them, that they were turning her into a different person.

The Steven Universe movie is coming out today. After that, it will be goodbye Steven?

You can use a shield in so many different ways. It’s about protection, but from what?

Like if you are feeling powerless and unseen, for example. That might grow and grow inside you until it becomes a torpedo pointed at everything and everyone, saying, Hey, look at me. Bow before my power.

But this inside-out kind of weapon is very temporary. It costs a lot, and only gets one use.

Masculinity: glass that has been blown out for a single use, and it shatters.

Resmaa Menakem, in his book My Grandmother’s Hands, borrows the concept of “blowing trauma” through others. This, he writes, is what happens when cops take their own shit out on Black bodies; when anyone beats their children, reenacting the beatings that their ancestors once took.

Susan Raffo writes of the need for white men to practice “losing control”:

Everything has a history. Every pattern of power and oppression has history behind

it. These patterns are held in our bodies, passed down from parent to child, turned

into culture, protected as the ways in which we survive. Everything started

somewhere. Everything has a before.

If white men are taught to stay in control, to not show vulnerability or emotion or anything “feminine” — that doing so risks punishment, violence, belittlement, ostracization — that safety, dignity, and belonging are all at stake —

then why wouldn’t we start to develop our bodies, in response, as a kind of weapon?

No one says, Yes, I am a glass shield that, once broken, turns to shards. No one says, I will blow my disconnection from myself straight through you as rays, spears, bullets.

All you say you want

to do to yourself you do

to someone else as yourself

and we sit between you

waiting for whatever will

be at last the real end of you

— Robert Creeley, “Anger”

On my sabbatical, not only am I relearning to write, I am relearning to nap.

I am supposed to be working on this essay. It is after lunch. The rain is coming down. I get in bed, pull on a sweater even though it’s still summer. I’m just going to rest a little.

I let my white-man body rest fully down, all the way, let go of the need it thinks it has to be productive (even at resisting oppression).

I know exactly what I’m doing.

Tricia Hersey speaks of her Nap Ministry: that as a graduate student and Black woman, working and studying, and exhausted, she began taking naps in public. She would read and read about the history of the place she was in, about her ancestors, about slaves working twenty hours a day in the Southern summer heat, and she would go to write about it and some part of her would fold and say — no.

And then she’d nap.

I don’t mean to equate my own rest with her Black ancestral voyage toward rest. I am trying to draw a dotted line connecting us, from this page over time, over meadows and railroads.

Hersey, when asked, Who is the Rest Gospel for?: “This is for everyone….Capitalism treats everyone as machines….White supremacy affects everyone….The full system of supremacy scams us all, just in different ways.”

Steven had migraines. My uncle. It is one of the reasons my mom has always given. He had trouble sleeping. If only.

In the movie trailer for Steven Universe: The Movie, Steven is really excited to rest. He has been liberating a lot of planets from the old imperial order and is pretty worn out. He’s lounging out in the sun, finally. He’s a little older, even. His voice has changed. He’s doing normal hybrid-human-gem things.

That, of course, is when the new villain comes.

You may be thinking, Wait, I thought Steven never gets older! What implications does this have for how we are engaging with masculinity in this essay? Reader: I am right there with you.

I am almost done with my mini-sabbatical. Soon I will go back to work — to Zoom meetings, to email, to fighting for the kind of world I want to live in (because I have the kind of weird job where I get, mostly, to do that). Still, a question is: Will I be able to take my naps with me?

You want, I understand, a central question. Something more than “this train wreck of masculinity, web of trauma and supremacy, and how to transform it.” Something more than just “and always ever on.”

When you go to sleep, for a nap, you feel tired and down sometimes.

When you wake up — if it is a good nap — you feel more rested.

You have valued yourself, even loved yourself, to take a nap.

To consciously, deliberately slip into one. Where there is no shame in resting.

The core of this essay is “how to prevent suicide and or mass shootings by putting men back in touch with ____________.”

[Take a minute to answer.]

To nap is to consciously choose to end your productive day (life) before its time; thus, napping is analogous to suicide, only inside out, recuperated.

To mass-murder is to put other people down, by force, to a nap from which they will never wake.

Because you, yourself, are tired.

[Take a minute to answer.]

If those men who commit mass murder and suicide could instead practice ____________,

we could transform, I believe.

I mean, this suicide stuff was always around, if you were of my generation and loved music.

One of my early memories is of where I was when I heard that Kurt Cobain had died. Back porch, old house, staring back at my parents. The loudest, most obvious example.

But it was like half the singers of those bands! Layne Staley (d. 2002); much later Chris Cornell (d. 2017); Jeff Buckley, in his own soft and ambiguous way (d. 1997, accidental drowning).

All my early male role models of feeling.

Vic Chesnutt did it later, too, in the aughts, but not before making one of the most beautiful songs that exists.

His case (was it different?) was different, trapped as he was in (nope, it was not different).

A fun story about my life is that Kristin Hersh of the band Throwing Muses used to babysit me.

She and Vic were close friends, but I didn’t know that until after I found and loved the song. This is really just coincidence. But you can think of her holding my little baby body, with all its male-assigned parts, still loose in their signification.

I’ve been thinking about something I probably need to do in this essay.

If I promise you that I — Adam Roberts, the writer of this essay — won’t commit suicide, it’ll just put the thought in your head that I had been thinking about it.

But if I don’t promise I won’t commit suicide, you might worry about me, and that worry might get in the way of you sitting with some of what I want you to be able to sit with in this essay.

Anyway, I promise.

My mom has already made me promise, dummy.

If I committed suicide, how could I prove to you the possibility and worthiness of men’s healing?

In the Guardian, Peter Ross writes of Scott Hutchinson’s surviving brother and bandmate, Grant:

Grant wants to be able to enjoy listening to the music of Frightened Rabbit again.

“I’ve got two nieces and a nephew through my older brother, and I hope to one day

have kids. And I want Scott to be a big part of their lives.” He would like to be able to

play the songs to those children and say: “This was your uncle. This is what he

sounded like. This is what he did with his life.”

For Steven to age — to be at least part human — is for him to change.

It is also to risk his healing powers against the powers of adult masculinity, patriarchy.

To risk, as a man, having a future.

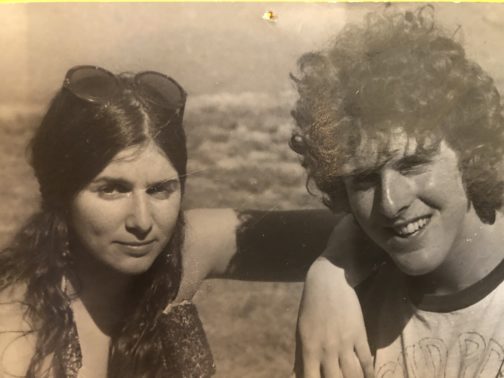

Looking at this, my most favorite picture of my mom and her brother,

I am reminded of absolute fierceness, of life.

My mom, in particular, is radiant — defiant, even. You can’t ever take away this moment.

My mom also shows me a final letter she wrote, during her mourning.

In it, I am reminded of the suffering that ties us, as various humans who have suffered in our own various ways, specifically, across such incredible expanses of time.

That said, I disagree with part of what my mother says in her letter.

Though she is, in the technical sense, correct — Steven has no reality for me; my grandmother has no reality — I cannot help but think I can feel them in my grief, my joy, in the co-presence of those sensations in my body.

Slow waves through my gut; very fast with the wind flying by.

The co-presence of grief and joy must be something like what it is to experience time.

Aliveness and its absence, which is not death.

I mourn the absence of my uncle Steven. That he is away from life, though I feel him vibrating here, somewhere, across time.

[Goodbye, Steven.]

I pick up a star that, far away, looks like it might be a gem of

some kind.

I don’t know where to put it.

Have you discovered your weapon yet?

How are you going to use it?