Jacob is given a rock and told, “Here, hold this.” The rock is palm-sized and solid and gray, the kind of rock you might find on a riverbank somewhere, commiserating with other unremarkable, nondescript rocks. Do rocks commiserate? “Wait,” Jacob says, “I don’t want this.” But the rock givers have already gone.

Jacob sits on the couch and considers the stone. It really is like any other stone. It weighs about as much as a sack of pennies, or maybe a half-sack. It isn’t exactly perfectly round—is it?—more oval-shaped but less oval than an egg, like if oval and round were combined.

A familiar grayness descends on Jacob’s heart. He blinks and looks at the TV. Quite a thing, TV. Three hundred and twenty-five channels, twenty-four hours a day, anything you want and yet: What do you want? What’s missing? What is it you want?

A news anchor with hair like a beach break is covering an accident on the 5. Rain and tired drivers and dark roads. “Tragic,” his co-anchor says, long hair and glinting gemstone eyes.

“These things happen, Janice,” he says, with a pronounced and practiced sigh. “Stay safe out there, folks.”

“Of course, these things happen, you jaggoff,” Jacob thinks. There’s no need to announce it. He changes the channel, the clicker in his right hand, in his left the stone.

Jacob wakes with a briny taste in his mouth, like pickle juice or the last of a beer after you’ve run your tongue desperately around the bottle’s rim. What a cliché. The rock is still in his hand. He’d fallen asleep on the couch and woken with his fingers clamped around it like a—what? Like a stone. His mouth tastes like brine and his fingers ache from the clutching, from his hand pressed in a weird way under the stone against the couch.

He looks like people you see on the street and you think, “Jesus fuck, what happened to that guy?”

In the bathroom, Jacob looks at himself in the mirror. Here’s Jacob: thirty-four god-damn years old, rock in his hand, beard like a troubled distraction, like an itch, the red eyes of someone sleepless and wild. Here’s Jacob, tongue-cottoned and pale, ragged and unkempt. He looks like an old man, or like an old man dipped in wax. It’s bad. He looks like people you see on the street and you think, “Jesus fuck, what happened to that guy?” His beard is a dead animal glued to his face.

Is this a metaphor? Don’t be stupid. Of course it’s a fucking metaphor. Not the beard, you idiot—the stone. The fucking stone.

Best he can, Jacob splashes water on his face and, with his not-stone hand, brushes his teeth. A shower, the thought of it, returns to him like a long-lost relic, and he awkwardly wriggles out of his t-shirt and jeans. It strikes him that everything he’s wearing, down to his briefs, is at least, what? Three days old? He feels a distant, indirect disgust toward himself, not like finding a rotten thing buried in the fridge, but a photo of a rotten thing, or like a detailed description of rot in some unexpected place, like at the back of a men’s magazine. He doesn’t lather up, just lets hot water cascade over his shoulders and head and back. The rock, too—water cascades over the rock. And it feels good, the water running over his shoulders and back, so he stands there awhile, who knows for how long, for however long it takes to play out the hackneyed sad-man-showering scene.

After his shower, he glances at his phone and sees a surprising text. Well, of course he does. This whole thing is full of tropes and clichés. That’s something no one tells you about all this—how when it comes, when it really comes, it’s chock full of tropes and clichés.

The text is from Tad. “Still on for tonight?”

Fuck. Jacob’s got plans with Tad tonight. He forgot. He entertains the thought of canceling, but he can’t cancel. Of course he can’t cancel. Of course he’s already canceled like three times. Jacob feels plans with Tad like a kick to the gut.

“Sure,” he writes back. “O’Rourke’s?”

”You’ve done it now, dickwad,” he thinks, tossing the phone on the bed. He’s aware of how theatrical he sounds. He kind of doesn’t care. He lies back on the bed and splays his arms out, rock in one hand and no rock in the other, and closes his eyes. Pan out to some spot just behind the ceiling fan’s whirring blades, rock in one hand and shit-all in the other.

O’Rourke’s is a place just like you’d expect from a place called O’Rourke’s. Mahogany beams everywhere and brass-lidded lights, but also waitresses in matching shirts and little trivia cards at all the tables.

Thomas Edison, inventor of the light bulb, happened to be scared of the dark.

“So, what’s going on with you?” Tad asks, eyeing him from across the table. Tad sips his beer two-handed like an old biddy with her tea, the pint at his lips and not-subtly-at-all looking at Jacob’s stone.

“Me?” Jacob said. “Not much. Got this rock.” He lifts the stone for Tad to see, even though they both know Tad’s already looking at it.

“Yeah, what’s up with that?” Tad forces a chuckle. Funny, how god-damn transparent everything’s become, like a game. You chuckle heartily to loosen me up so I’ll go crrrrrk and lay my heart on the table, all so you can what? Say you called the guy? Tell people I saw Jacob. He seems all right?

“Oh, you know.” Jacob shrugs. “It’s my stone.”

“Where’d you get it?” Tad asks with genuine fucking interest. Jacob wants to punch Tad’s genuine interest in the face.

“Stone Emporium,” he says and sips his beer. Just then the waitress shows up. She’s different from the drink order girl. She’s got her hair in a high ponytail and has green eyes and a nametag that says Jenny.

“Hi guys!” She smiles brightly, like this isn’t the worst place on the planet, like she doesn’t hate her job. “How we doing tonight?”

“Good, thanks,” Tad says, making to order, but then Jenny sees the stone and does that thing, that flirty waitress thing. “Nice rock!” she says.

Jacob looks up at her and flashes his once-winning smile. “Why, thank you.”

“Do you collect them?” What a coquette! “Or are you building a wall?”

Jacob leans toward her suggestively. She’s flirting for tips, he’s flirting to piss off Tad, but who cares. Flirting feels good, and it’s been a long time since something felt good. “I’m building a wall,” he says. “Wanna help?”

“All right,” Tad cuts in, clearly annoyed. “I’ll have the corned beef.”

“Sure,” Jenny says, and writes it down. “For you?” She turns to Jacob again, that million-dollar, serene smile spread across her face.

“I’m good,” Jacob says, then lifts his rock. “But my friend here would like a beer.” Boy, that gets a laugh. Jenny and her laugh like a gold coin.

Tad and Jacob don’t speak for a long-ass time. Football on the corner TV’s. Tad weirdly seething across the table and Jacob doesn’t care. What does Jacob care? Tad sips his beer and sort of slams the glass on the table. “Can you just put that thing down for a minute and talk to me? Just talk to me and put it down?”

“I am talking to you.” But obviously he isn’t.

“You know what I mean.”

“No, I don’t. I don’t know what you mean.” Jacob looks straight at Tad then, daring him to something. To what? Who knows.

Tad looks away and starts doing that little headshake thing people do when they’re pissed, like a twitch or a bobble on the end of a stick. Whatever. Jacob picks up a trivia card: Vincent Van Gogh only sold one painting in his whole life. When Jenny comes back she must catch on to the tension—who wouldn’t?—cause she sets the corned beef on the table and walks away. She doesn’t even glance at the stone.

Here’s Jacob, in the grip of incomparable sorrow, being a total jaggoff to his friend. Insert interior monologue: What am I doing? When did I become such a dick? Hadn’t Tad loved him too?

All right, so come out with it already. Why all the heavy-handed beating around the bush? You want the details? All right, jaggoff, here’s the fucking details: Six months ago, Jacob’s best friend Marco was killed in a car accident. Big surprise, huh? Guy with a rock and an insufferable beard, deep in the clutches of mourning. Whoop dee do.

They’d known each other since grade school. Marco lived with his dad and sister in the house across the street, moved in the summer before third grade. It was the sort of boyhood friendship that begins in wide arcs, Jacob eyeing Marco with suspicion and curiosity from windows, the garage, the front yard. One day Jacob’s dad says “Why don’t you go introduce yourself, instead of staring all day?” The thought alone was like a grip on his balls, Jacob with his total ignorance about making friends. “Oh, for Christ’s sake,” his dad said, sort of half-stomping to the fridge for some beers. “C’mon.”

Marco and his dad were in their garage, tinkering with tools. Jacob trailed sheepishly behind his father, who strode up the driveway. “Hey there, neighbor! Thought we’d come over and introduce ourselves.” Shortly the two men were at it, talking baseball and drinking beer. Jacob stood awkwardly by the tool bench, watching Marco and working his toes inside his shoes. Marco didn’t ignore him, but he didn’t not ignore him either. He was simply absorbed. Sooner or later Jacob’s dad goes “What are you working on there, Marco?” and “Oh yeah? Jacob likes to skateboard too,” and “Go on over there, Jacob, help the man out.” God how Jacob hated that shit, his dad’s bullshit and uncanny abilities, his “Look, son! Look how easy it is!”

What happened next? Did they skate that afternoon? Strangely, that part—the part that matters—is a weird blur, just Jacob’s dad with beer in his moustache, laughing and laughing with Marco’s dad in the garage.

Anyway, that’s how they got to be friends. Marco was an easy-going kid, liked to skate and draw rocket launchers and watch scary-ass movies on TV. They’d be sprawled on the floor, a big bowl of popcorn on Marco’s lap, Jacob practically shitting himself as some kelp dude crept out of a foggy swamp, and Marco’d go, “Pfft, yeah right,” shoving popcorn into his mouth. Marco’s Tony Hawk posters, his pile of skate shoes, his Mad magazines. Taking to junior high like a champ, the rest of them flopping around like retarded fish. Something otherworldly about him, always, something removed. As if, not only was this not his first rodeo, but he’d been to the rodeo a thousand times, knew how the fucking rodeo was built. And why? Who knows why. Maybe on account of his dad letting him do whatever—or not whatever, but you know—or his sister, Corina, who was older than them and super chill, or maybe on account of his mom’d died when he was three. Whatever it was, Marco was always just that much removed—or not removed but ascended.

In high school he didn’t party, he didn’t drink, and everyone loved him anyway. Marco with his Krink markers and his knit cap. He’d high-five the Down’s kids in the hallway, but not in a fucked-up way like everybody else. Just like, “What’s up, dude? Give me five.” Probably everybody says this stuff about their best friend who’s dead—He wasn’t like anybody else—but fuck you. He wasn’t.

Case in point: he could’ve ditched Jacob at any time, probably should have. Jacob with his acne and his occasionally high-strung ways. But he didn’t. When Marco’s dad invited Jacob to the family lake house the summer after ninth grade (Jacob’s dad: “Aren’t you afraid of lakes?”), this thing happened that probably wasn’t a big deal but felt like a big deal at the time: Jacob saw Corina naked. Or half-naked anyway. He didn’t mean to—there was this little changing cabana down by the shore, off a trail that bordered the lake, and maybe the door didn’t work or she’d forgotten to close it all the way. He’d been off in the woods and when he rounded a bend in the trail there she was, stripped to her waist in the little shack, smearing lotion on her legs. He could’ve or should’ve run, or not run but looked away—but he didn’t. He moved himself closer to a tree and then watched: Corina’s perfect breasts moving back and forth, just so, as she worked lotion into her ankles and then her shins and then her thighs. He was fourteen and had seen breasts before, but never like this, live and in the flesh, dangling deliciously above two golden knees. He got so hard in his shorts he thought he might explode.

It didn’t last long. Within seconds he realized what he was doing—peeping on Corina’s boobs—and he ran back down the trail. He became wracked with guilt—he was a creep, an asshole, a fucking perv—and something must’ve shown on his face, because Marco finally asked him what was wrong. Jacob shook and sweat and almost puked when he told him. But Marco, cool as beans his whole life, just put his hand on Jacob’s shoulder and said “Relax, dude. They’re just tits.” Fifteen years old, that’s what he said.

Insert memories of an overwrought funeral scene.

Insert memories of an overwrought funeral scene. Insert leaves rustling in the trees above Marco’s grave. Insert a sea of black suits and dresses. Jacob can’t remember if the women wore hats like they do in the movies, but go ahead—insert those too. Insert all the distraught faces, all the people who’d loved Marco, and Marco’s dad and Corina in the front row, not really crying but not not crying either, sitting close, holding hands. Insert some preacher’s necessary but bleak refrain, ashes to ashes, back to our heavenly home, yar yar yar. Later, at the wake, during share time—who’s idea was that, share time?—broad-shouldered men knuckle tears from their eyes while they talk about Marco, what a genuine, good dude, and share anecdotes that makes laughter crack like a whip through the room until finally they are overcome and their voices snap and they have to sit down, collapsing like puppets into their chairs, while their wives embrace them and weep with them too. Insert obscene mountains of sandwiches, little bowls of almonds and olives, fruit bread and cold cuts and cheese logs and cakes. At one point have Jacob look out the window and see Corina, smoking by herself in the driveway outside. He’s never seen her smoke before.

While you’re at it, go ahead and throw in the days after, the weeks, the months. Make them as god-damn gut-wrenching and movie-ready as possible. Throw in the sleepless nights, the yearbooks and boxes of photos. Insert a tally of empty beer bottles like a body count. Shit, might as well toss in crying on the floor, because that happened too—happens sometimes still. When it does, every single time, Jacob finds himself thinking, in some dense outer reaches of his brain, “Seriously, dude? Crying on the floor?” Or he pictures Marco, sort of laughing at the absurdity of it all, him dead and Jacob crying—but then reaching down, maybe, helping Jacob up off the floor, then hugging him and saying something like “Let’s go eat ice cream like school girls.” Or something dumb and funny like that. Always something dumb and funny like that.

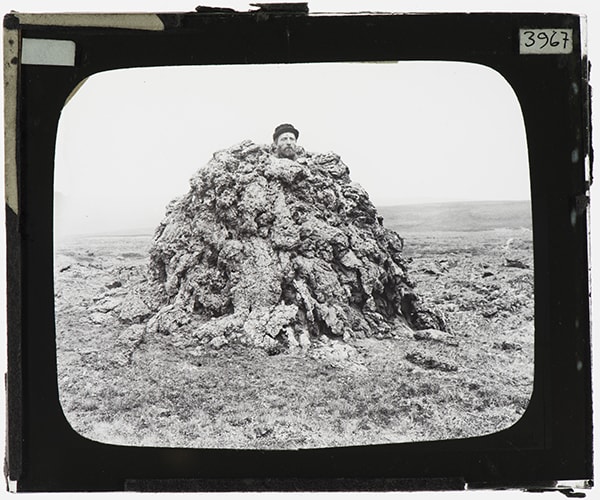

The rock grows. Of course it grows. What begins as a tangerine-sized stone in Jacob’s palm soon swells to the size of a softball, taking up all of his hand. Surely this isn’t your first rodeo either, so you must understand that the growth is metaphorical too. His hand curls around the thing the way you might clutch what you are about to throw. With his hand level to the floor, Jacob can just make out the edges of his fingernails, the dirt underneath, his palm almost completely obscured. It feels natural at first, and then his fingers begin to buzz and swell, and then he can’t feel his fingers at all. He keeps his arm crooked near his ribs, the stone held before him as if on display. His elbow grows stiff and achy, then seems, miraculously, to conform. At first, pain shoots down his arm, white hot sparklers from shoulder to elbow to wrist, then in a matter of days the pain blooms into a comfortable numbness and now, he’s certain, the bicep on his left arm, his stone arm, looks muscled and practiced and mature—a man’s arm, not the shit arm of some little girl. And yes, living with a stone clutched in your hand—there are practical considerations to be had, sure, but it’s frankly not that big of a deal. He dresses one pant leg at a time, just like anybody else, his left pinky hooked through a belt loop as he shimmies his pants past his hips. Shirts are not a problem because he never wears button-downs, though he’s switched to laceless shoes. When he drives, the stone hand nestles comfortably in his lap and there are times when he hardly remembers it’s there.

His biggest challenge is maintaining consistency and composure at the medical supply warehouse where he works. Bed pans, ace wraps, and crutches can all be done effortlessly with one hand. Walkers, if they’re on a higher shelf, are a bit ungainly to take down and unfold, but otherwise not a big deal. The main obstacle, by far, are the oxygen tanks. Clearly, the M2s, M4s, M6s’ are nothing, no problem at all, but those first days at work the M90s glare down at him, menacing behemoths that taunt him with his fucking stone. He stands before the shelves in aisle C2, scrutinizing a cumbersome, daunting wall of tanks. “Fuck,” he says under his breath, this part having completely escaped him, though it encompasses nearly eighty percent of his job: wrestling giant oxygen tanks off of shelves and onto carts and into trucks. How had he forgotten this part? The place is called Foothill Oxygen and Medical Supply, for christ’s sake—“Medical Supply” thrown in as an afterthought even, a shitty tip. “Fuck me,” he says again, Rochelle passing the aisle then with eyebrows raised as if the rest of them have been anticipating this all morning, every last two-handed one of them. He takes a deep breath and puffs it out fast, like blowing away dirt, the determined exhale of an athlete or a politician about to take the stage. He flexes and wriggles his right-hand fingers then grabs the nozzle of a second-shelf tank. He slides the tank to the edge of the shelf with extreme care, then tucks his rock arm under it as he pulls it down. Of course, the fucking thing slips, jumps from his hand and crashes loudly to the floor, the sound echoing in the cavernous warehouse, a sudden jolt over the incessant chatter of the talk radio blathering in the corner. “Oh damn!” he hears someone in the next aisle say, probably Ron, and he thinks, “Fuck you, Ron,” then remembers Ron’s on vacation with his family at a cabin somewhere. He’s been talking about that cabin for weeks.

That’s the only tank he drops. He realizes swiftly, necessarily, that it’s all in the legs, how if you tripod yourself you create a balance that’s nearly indestructible. (Physics 101, dumbass.) At the grocery store, pumping gas, out and about, people either stare or they don’t stare. His world is half-filled with half-opened mouths and half-filled with averted eyes. The staring ones are mostly those gorgeous, obnoxious Cal State girls, girls with flawless skin and commercial-ready hair who’ve never known a moment of ache in their lives. At times, when he sees or feels them at the edge of his field of vision, obviously staring from behind their phones, he’s overcome by brief moments that are filled with a profound mixture of envy and pity for these guileless, beautiful creatures who know nothing yet of pain or loss. Other times, most times, he thinks, “Fuck you, you useless twat,” his heart a scrunched-up, pitiless little ball. “Just you wait. Just you fucking wait.”

On Monday afternoon, Mike Midken calls Jacob into his office for, you know, “a chat.” Mike Midken’s the kind of guy who goes “Okaaaay,” with too many a’s, like everything’s a problem to be solved and all you have to do is smile and chuckle and shuffle papers around on your desk while you say “Okaaaay” with too many a’s.

“So, Jacob,” Mike Midken says, shuffling papers around on his desk, “Mr. Leonard and I were having a little chat yesterday.” Mike Midken, in case it isn’t obvious, is not Jacob’s actual boss. Mr. Leonard is. Mike Midken is not anyone’s actual boss. “Mike Midken” is not a name that commands authority. “Mr. Leonard” is. But Mr. Leonard is a busy, important man. Mr. Leonard can’t be bothered with any of this, whatever this is.

“We wonder how you’d feel about being out of the warehouse for a little while. Maybe put you on clerical for a couple of weeks, see how that goes,” not-eying Jacob’s stone.

Jacob looks at Mike Midken and blinks.

“Why?” he asks, not intending to sound clipped and defensive, or maybe intending to, who knows.

“Why?” Mike Midken repeats, like this is the first time in history the question’s been asked.

“Yeah, why?” Why why why why why, like a child, a three-year-old. Why, Mike Midken, why? Why take me out of the warehouse? What the fuck do you need in a warehouse man that I can’t do? What possible thing could there possibly be that I can’t do?

“Jacob.” Mike Midken says his name with finality, like it’s a whole sentence unto itself, his eyes squinted in a you’ve-got-to-be-kidding-me sort of way. He nods, cold sober, at Jacob’s stone.

“Yeah, okay,” Jacob says. Really, there’s no arguing with the stone.

Thing is, they’ve all got stones. Mike Midken keeps his in the top drawer of his desk, pulls it out every Friday just before five, cradles it in his hand near his cheek—because yes, about a year ago, he lost his wife. Dana Ross, the secretary, she keeps hers perched in the center of her desk. Her mother’s been dead a number of years. Rochelle keeps hers under the seat of her delivery truck, and Wayne takes his out and starts waving it around after what? Like three beers? Even Mr. Leonard has a stone, a really big one, because his son drowned in a boating accident late last year. Recently, Jacob’s begun to think about Mr. Leonard’s stone, slumped like a beast on the Long Beach dock. He thinks of Mr. Leonard—that rich, fantastic, distant fuck—on a spring afternoon, starting up the engine of his massive, dazzling yacht, skillfully weaving through a boatyard filled with other massive, dazzling yachts, tipping his chin at all his rich fuck neighbors, who sit on the decks of their ships drinking mai tais and wearing stupid khaki shorts. Lucidly, Jacob can picture Mr. Leonard—slipping past the other ships, revving his engine just outside the gates, bouncing over white cap waves as the sun fades in a reddening sky, out past the shoreline kelp beds and striped buoys, farther out and farther out and farther out, out to where the ocean is a black pit seething beneath you and the sky? There’s nothing in the sky—no planes, no halos from city lights, just the deep nothing of space and the diamond-bright stars.

Mr. Leonard can sail as far as he wants, so far he doesn’t know where he is anymore—it doesn’t matter. He can sail and sail and sail, but his rock will still be there—that great, hulking mass—waiting patiently for him on shore.

Mike Midken says, “Let’s put you on clerical” while Mike Midken knocks cheerfully on his desk, then Mike Midken leads him down the hall to a little closet of a room, a tiny pisshole of a room. He says things like “What you do is” and “You got it, bud” and gives Jacob a stapler and two stamps, Pending and Closed, and then disappears whistling down the hall. Is this the worst day of Jacob’s life? Don’t be a moron. Still: in less than an hour, Jacob’s gone from the dignified land of manual labor to the land of clerical, from the open expanse of the warehouse with its high ceilings and endless shelves to a closet that’s damp and stinks vaguely like piss, where Mike Midken keeps poking his head in and going “How we doing, pal?” and Dana Ross, sweet old Dana Ross, walks in and goes “Oh!” with genuine surprise that he’s there, then glances with sad slow eyes at his hand on the desk, holding the stone. Because of all this and everything else—the pain in his chest impossible to describe, like a steel claw grabbing hold of his heart and squeezing with unforgiving force, twisting his heart, mangling his heart, hardening the blood in his chest to ice, to stone—because of it all, Jacob clocks out and resolves, like making a calculated, rational decision, to get really, really drunk. He’ll start at O’Rourke’s.

The thing about clichés is they have to be earned. You want to earn a cliché? Love someone, then have them die.

The thing about clichés is they have to be earned. You want to earn a cliché? Love someone, then have them die.

There it is: earned.

O’Rourke’s is as empty as a cave. Not actually, but still, it’s not a very lively scene. A couple of coats-off stooges are at the bar, the kind of guys who play rugby on the weekends and then fuck someone who’s not their wife. There’s an old guy in the corner with a newspaper spread in front of his face, an untouched Reuben on his plate. Other than that, cave.

Jacob scans the place for Jenny—behind the bar, the little station by the window. Ever since he was here with Tad, Jenny’s been this nagging presence in his mind, not like a thought but like the shadow of a thought, or like something you think about really only once you are there, scanning the not-crowd, like, Oh yeah, what’s-her-name. Good ol’ what’s-her-name.

A girl who is not Jenny, not even close, comes to his table.

“Can I get you something to drink?”

“Uh, sure. Got any craft beers on tap?”

He tries not to stare at her face while she describes the beers—a pilsner with hints of raspberry, a Rogue River something—but her teeth are like hockey pucks, or like something a hockey puck would knock out, big and unglamorous. She’s got freckles like hand-slaps across her cheeks.

“I’ll just have the first one,” he says, cutting her off. Did he cut her off?

“The pils?”

“Yeah, that.”

“Cool,” she says in a way that’s not cool at all. She doesn’t even look at his stone. Even her ass is boring as a dinner plate.

He thinks “I wonder if Jenny’s here,” as if he hasn’t already thought it. He waits for his beer. Trivia. The blue whale is the largest animal in existence. It’s the size of 1800 men.

Hockey face comes back with his beer. “Thanks,” he says. “Hey, uh, is Jenny here tonight?”

“Jenny?” Hockey says, with a weird mix of skepticism and disbelief, as if he’s asked if she has an extra arm and oh, hey, can I borrow it?

“Yeah. Jenny?” You know, Jenny? He taps his chest where a nametag might go but realizes this, as a gesture meant to clarify, makes no god-damn sense.

“Yeah, no. Jenny’s not here.” And then she looks right at his stone with total contempt. He’s got a trivia card perched against it like a place card at a fancy table. “Nice rock,” she says, then walks away.

What the hell? How come ugly girls are always such bitches? Or not ugly, but like, not Jenny. The beer tastes like someone’s dumped salt on some old fruit. Your heart beats 100,000 times a day. Your thigh bone is stronger than concrete. Where’s Jenny?

You know how waitresses have that annoying habit of materializing out of nowhere to offer you what you want? Hockey does that.

“Another beer?”

“Yes,” he says, all business, eyes on his trivia as if it’s the most important trivia in the world.

Salted fruit. Gross. Oscar the Grouch was originally orange. He thinks about Jenny, her beautiful, sculpted cheeks. Are they sculpted? Or round like his stone? He holds it close to his face. It’s still nondescript, still a dull grey stone. The inventor of the Pringles can requested that his ashes be buried in one. This time when Hockey comes back he doesn’t even talk to her, just taps the rim of his glass like important men do. He wishes he had a pen and some paper, some kind of business report, something that says “Important Man.” Hitler’s nephew once wrote an essay called “Why I Hate My Uncle.” Did he eat today? Babe Ruth kept a cabbage leaf in his hat. Suddenly he remembers Tad. Tad! Where’s that guy right now?

“Hey man,” he texts, thk gd for autacorrict. “Wanna meet me at O’Rourke’s? Beer tastes like salted fruit.” He realizes, vaguely, that this is not a selling point. He glances around for Hockey and lifts his empty glass. Her face remains neutral as he orders, neutral as she sets it down. He feels a watery, peripheral worry, like, “Are we fighting? Is this a fight?” Salted fruit. Where’s Jenny?

Slow, a little drunk, he looks down at his stone. Two nights ago—was it two nights?—he dreamt that his hand shriveled up beneath it, his fingers crude and wrinkly and hard as stale raisins, and when they fell off, just the tips, he put them in his mouth—one by one, slowly, deliberately—and swallowed them whole.

Everything fucking sucks. He feels this now as a full-blown revelation, a dead weight jostling his bones.

Everything fucking sucks. He feels this now as a full-blown revelation, a dead weight jostling his bones. Where is everybody? Where’s Corina? Where’s Jenny? Where’s Tad?

“Here you go,” Hockey says, placing his bill on the table.

Wait, what? He wants another beer.

“We have a four-beer house policy,” she says. This is clearly bullshit but something, strangely, has softened in her eyes.

“Jenny’s not here? Jenny’s gone?” Whoa, talk about drunk.

“Mm hmm, Jenny’s gone.” A new, gentler tone.

Jacob feels punched. All he wants to do is fuck Jenny until her eyes pop out of her face, or no, just lay his head in her lap forever. He feels suddenly, strangely, as if he might cry. If he does it’s going to overwhelm him, tears gushing, flooding his booth, the bar, all of them, sweeping up Hockey and old Reuben and the coats-off guys and whisking them all dangerously away.

“All right, bud. Let’s go.” A manager type has appeared. Wait, is he crying already? Hockey stands over by the bar, her hands sort of folded in front of her, watching quietly as if suddenly an understanding exists between them, as if suddenly they’re friends.

Oh, keep a journal, Jacob. You should think about therapy. There’s a marvelous grief group Wednesdays at the United Methodist on Main. Take an art class, Jacob. Art saved my life. How about a trip? Wouldn’t a trip be nice? You’ve always wanted to see the world. Didn’t you used to talk about Spain? You should go to Spain. You know, when Larry/Bernice/Naldo/Marquel/Tina/Beth/my dog/my aunt/your father died, I packed up/sold/burned/gave away everything I owned and just left town for a month/six months/a year. You should leave town. You really should go on a trip. Doesn’t your uncle have some land in Hawaii? You should go there. Bring a journal and go to Hawaii and just be, Jacob. After ______ died, it saved my life. Journaling/traveling/moving/writing/art, it saved my life.

Amazing, callous even: people advising you on death and circling back, always, to life.

Once, about two months ago, his mom’d said, “Step in, Jacob.” She actually said that: “Step in.” They were sitting at her kitchen table, and she’d leaned back and spread her arms like Jesus, like inviting the whole world in for a hug, and she just kept saying it, over and over, her eyes alight with meditation and poetry and Gratitude with a capital G, all that shit she’s been into since his dad died. “Step in, step in, step in.”

Shit-canned, grieving motherfuckers should not drive, but anyway that’s what he does. He parks on the street and stumbles up the front steps, knocks formally like a visitor. The porch rolls beneath him and he thinks, “Look at this fucking porch!” His dad built the porch with his own bare hands. Figures.

“Jakey!” his mom exclaims when she opens the door. “It’s nine o’clock!”

“Mama!” he says like a surprise party, like glowing cake. He’s never called her mama before in his life.

“Oh, for goodness sake,” she says, shaking her head. “You’re drunk.” She opens the screen door and he stumbles inside.

“Mama! You’re so pretty, Mama!” He clumsily pets the outer ridges of her hair. He’s sloppy drunk. Is he sloppy drunk? Or is some of this for show? “Sloppy,” he thinks. “Slop slop.” His mama has such pretty hair.

“Okay, sit down.” Mama, pretty Mama, leads Jacob to the kitchen table. His papa built this kitchen. His mama and his papa lived in this house. But then his papa died. “Mama, where’s Papa?” His face feels leaking or cracked.

“All right,” she says, like knock-it-off, and sets a cup of coffee on the table. She watches him sip. Mmm, coffee. His mama’s so pretty. She looks like she slipped out of a pretty tin can. “Where’ve you been tonight?” she asks.

“I’s at O’Rorsees,” like a grown-up, like thankyouverymuch.

“With Taddy?”

“Nononono,” he wags his finger. “No Tad. No Jenny, no Tad.”

She nods and watches him. It’s nice or makes it a little worse, his mama watching him like out of a can.

Jacob’s mama regards Jacob the way you might regard a sculpture or a big cake, but maybe like a sculpture you built out of pieces of cake—whatever, you get it: like a thing you made or didn’t make but that you love anyway, in spite of, because of, always. (Is that enough of a cliché?)

“Let me see,” she says, meaning his stone, and he swings his arm clumsily across the table in a drunken arc. Jacob’s mama cradles his hand like she’s holding a precious jewel then gently, without asking, pries the rock from his palm.

It peels away with resistance, like hinged with the littlest bit of glue. Jacob’s mama winces as it comes unstuck. It’s not a pretty sight. The flesh of his palm is wet and mossy and white, putrid from weeks untouched under the weight of his stone.

“Oh, Jakey,” she says, the way mamas do when they mix disgust with concern. She takes a deep breath and shakes her head and does not look away. It isn’t so much his rotten palm that sobers him up, it’s the sight of his mother, his loving breathing mother, all that worry stitched across her face.

“Stay here,” she says firmly. He nods and lays his head down while she goes into the other room. Her own rock is perched like a monument on the sill above the sink. It’s a pocked, lava-like thing. Jacob’s father has been dead for three years. He had a heart attack while sitting in the car. Sometimes he did that when he got to a place—wouldn’t get out right away, just sat there thinking in the car. Drove Jacob and his mom nuts.

She comes back with a first aid kit in one hand and in the other his stone. He didn’t even realize she’d taken it. He sits up and holds out his hand, like an obedient little boy.

Jacob’s mom opens the kit and pulls his hand close. With tweezers, she begins to carefully peel away the flesh from the center of his palm, the skin there damp and loose like a blister long popped. She swipes it with an alcohol swab then blows cool breath onto it before it stings. She smears Neosporin on the patch with a Q-tip, undoes a roll of gauze, holds the edge down just past his thumb, wraps once, twice, three times, four. She does all this methodically, with ease, as if every day he comes to her drunk and in pain and every day she dresses his wounds.

Then, Jacob does begin to cry. His mother dresses his wound and lays his rock back into his palm where it belongs, and Jacob begins to cry. Not a man’s crying either, but hot, blubbery, sloppy tears. It’s a loud, hiccuping series of sobs that once begun will not stop. He feels lacerated and torn and furious and vulnerable and fearful and wretched and hopeless and wandering and lost and also, mostly, just really, really sad. “Oh, Jakey,” his mom says, pulling him close. “My Jakey boy.”

After a while, she brings him a towel and he swipes clumsily at his drenched face. The kitchen is quiet. Jacob leans into his mother’s arms and she rocks him back and forth, back and forth. They both look silently at his stone. Of course, there’s another stone, sitting at his house on the deck. It showed up the week after his dad died, and has sat there since, largely ignored. Jacob’s never even picked it up. Once, when Marco came to get him, he stood on the porch and said, “Dude, you gotta bring that thing inside.” It was clear he knew what it was and what it meant, but he didn’t say anything else.

Now, Jacob’s mom reaches out and takes this stone into her hand, and then, as if she’s intended it all along, flips it over and lays it back in his palm. He brings his hand close and considers it. The other side of Jacob’s stone is mostly like the first—dull and plain and grey—though it’s hard not to notice a slight difference there, a small spot like a smudge or a smear. It isn’t a heart shape or anything—c’mon—but there is something to it, the other side.