Samia Mehraj’s story transports us to a world of imperishable joys and beauty of childhood, the complicated pains of growing up, and the layered and bruising encounters with the world beyond. Stained White Curtain reads at once like a vivid dream and a realist, full-blooded depiction of sibling love, the discovery of the other, and the lasting effects of the political on the personal. This wholly original, tender, and beautiful debut is a delicately nuanced exploration of sisterhood, identity, belonging, motherhood, faith, home, and much more. Samia has a memorable voice and writes gorgeous prose. I first met Samia through the South Asia Speaks programme for emerging writers, and later in person on the shores of the Nigeen Lake, which embodies so much of our shared Kashmiri past and present. It’s been a pleasure and an honour to guest-edit Stained White Curtain. — Mirza Waheed

—

That August week, records shattered like glass. Delhi witnessed its heaviest rainfall in two decades, and its rickety local buses bobbed on the flooded streets like plastic bottles. Somewhere, an earthquake cracked open the parched mouth of an ancient volcano. The total number of those fleeing Syria steered by the winds of the Mediterranean reached four million. Another son of an Indian bureaucrat ran his Range Rover over the last witness to his latest crime. India topped the global charts on internet shutdowns with fresh restrictions in Kashmir—and Tabassum’s blood platelet count reached its all-time low. It was the week she was admitted to the Gangaram hospital, and the week I first heard Juicy’s voice.

Before we had found ourselves in that long, winding queue for a hospital bed, Tabassum had been recovering, and the rouge of her skin was slowly returning to her cheeks. But at her last check-up, one of her reports came back inconclusive. The doctor treating her dengue suggested we pay a short visit to a renowned haematologist who could probe deeper into the eccentricities manifesting in her blood. “See, such a low platelet count,” the doctor said, scratching her head with the long nail of her pinky, “is unusual and leaves her fragile enough to be infected by even the harmless bacteria in her body.” The happy and friendly microbes in her mouth and gut might now have second thoughts about their friendship, conspire against her and turn life-threatening.

We sat on a rusty metal bench outside the clinic, the monsoon puddles pooling at our feet. I let Tabassum rest her head on my shoulder and promised her we would see the best haematologist in Delhi—that was what mother and father would have advised anyway. That afterwards we could escape to a park, away from the watchful gaze of her hostel warden in Jamia Nagar, who kept her two basilisk eyes fixed on the hostel gate, and got her jollies by jotting down names of girls who broke her house rules. On all evenings, she collected fines from girls who returned even a minute late after her 6pm curfew, and counted notes that fattened her Made-in-India patchwork tote bag. The city, still a stranger to Tabassum, had its own introductions to make, and my promises would have to wait for more than just one visit to the haematologist.

Tabassum had started her studies at Delhi University just a month ago. Disoriented from her first visit to the city, she was met with conversation-starters where her curious classmates enquired about her home in Kashmir, the purity of Himalayan air and the impenetrability of the layers of her headscarf. They listened with their pupils dilated—with what they called a growth mindset—and shared how eager they were to visit Kashmir, to quench their lust for experiencing life in a conflict zone. The warden in the hostel had warned her against becoming one of those wide-eyed Kashmiri girls who, upon stepping into big cities, get so blinded by the bright city billboards that they end up bumping into lamp posts and wandering into places they don’t belong. The waterlogged, defunct air cooler in her hostel room had set off a mosquito fest, bitten arms, bouts of diarrhea, and over time, dengue. I was made privy to these details only after several doses of painkillers at the hospital loosened her jaw and accusations against Delhi floated up like burps and belches, and I, at last, became her confidante.

Tabassum and I grew up under the same roof, were fed and punished by the same hands, yet the idea of us being sisters amused the neighborhood. Tabassum was a private person; she spoke little, but when she did, her words often twisted the air. She had a biting sense of humor; but her advice held the warmth to repair. Our relationship had its seams and silences, always shifting, in flux, widening and closing. How had these come to be? A few reasons come to mind, but I’m as uncertain as a wide, wavering ocean, never sure about the true nature of my grievances or the root cause of her complaints. Sometimes, when you live through hard times with loved ones—people you think you know best—old layers of their personalities begin to peel away and from underneath, shines through a new skin. A newborn adult with a fresh set of little quirks and paradoxes. Yet, even in the knowledge of these new revelations, there was so much to envy about Tabassum and those gifted with the grace to guard their emotions and hold themselves back until a certain threshold is crossed. So poised, so self-sufficient she was in that hospital—it took me longer to recover from that week than it took her, although she was the one who had been ill.

We made our way to the metro station stepping over broken bricks dotted along Delhi roads that had now taken on the disposition of seasonal rivers. As the train approached, I seized the moment to quickly slip off my headscarf. The usual ritual—unpinning the scarf in haste while rushing through the crowd, an ear scratch to loosen the folds around my face, and finally a quick yank just before the metro came to a halt and spilled its bowels onto the platform.

Thirteen stations away from the hospital, we were packed in a cramped coach like soda bottles in a crate. The August heat left us drenched in sweat. Then the air conditioner poured in its cold currents, people shivered in their rain-soaked clothes, and sneezes rippled through the crowd. An achoo! here and an achoo! there, no room to sidestep or stagger against the jolts of the coach which caused us to sway together like trees. I wrapped my arms around Tabassum, stretching wide to shield her from the metro’s jostling, from the nudging and pushing bodies. All I could think of was the friendly bacteria in her body welcoming the deadly ones introduced to her by the infections in the Delhi air. Tabassum leaned her head on my shoulder, frustrated, and pointed to an uncle with earbuds burrowed deep into his hairy ears, his phone blaring cricket commentary on the speaker. To our left, a woman watched a tutorial on pairing belts with sarees. I wanted to ask them to lower the volume, but there were too many of them, and with Tabassum wearing her headscarf, we couldn’t have more trouble on our plate. I closed my eyes and gave in to the cacophony that surrounded us—of news, commentaries, warnings, daily soaps and catchy songs. Of women stuck at their in-laws, and ashwagandha stirred into drinks. Of Hyderabadis in Saudi and farmers in Punjab. Of workshops in China and enemies in Pakistan. And on and on we rode, station after station, Kashmiris in a Delhi metro.

Tabassum believed that no matter where we were—Kashmir or Delhi—Allah ta’aala watched our actions at all times, especially when we thought no one was looking. Delhi was the darkest test of our faith because here, our heads and headscarves were nobody’s business—not the Molvi’s, not the maasi’s, not the neighbours’. She kept good terms with Allah and believed that I had a tendency to stray. In my five years in the city, my covered head had only attracted eyes in the metro, contrary to the notes I was sent off with from Kashmir. On days when the news from home was particularly tense, the discussions often grew louder. I was often pulled into friendly chats that always led to the same question: “So, do you think differently from those Kashmiris?” Did I believe in pen-Kashmiris or gun-Kashmiris? There had been deliberations about which Indian state deserved Kashmiri brides the most, unsolicited lectures, wandering hands and strangers who would follow me home, telling me that they knew where I came from as though I had stolen from their grandfather’s wealth. I was told it wasn’t hard to spot Kashmiri women—they all have that nose and a bashful demeanor, regardless of how they dressed. Yet, the Kashmiri women I knew in Delhi were never of a single type; they were never particularly shy, perhaps more vigilant or indifferent than anything else. Strangely, when I let go of my headscarf, most of the time I was left alone, at least when I was in Delhi metro’s women-only coach — that is when the women’s coach only ferried women. Tabassum wasn’t fully privy to these details. After all, she had barely spent a month here, and I dreaded talking to her about it. She was feverish and homesick, and this discussion, too, could have fueled her silence towards me. Perhaps it was also because we both knew that this wasn’t the only reason I stopped covering my head.

***

Our first night at the hospital, unlike the next ones, is quiet but suffused with shuffles of feet, soft sobs of attendants and the variety of noises that patients make when in pain. We will hear Juicy the next day, her voice will chime through the ward dispelling the silence left from the first night. She will cheer for her son on a video call—shout, “Shaabaash, shaabaash!” to the mess the child has left in his potty pan. But the first night is long and stretches its arms over the large hall where Tabassum is assigned one of the beds in a corner. Between each bed hangs a curtain. Hers is beneath the blaze of a yellow bulb meant to burn throughout the night. It pulsates as though signaling an emergency, spattering its anxiety over the bed. To our left, a stained white curtain, riddled with holes, stretches from ceiling to floor, separating our small, confined space from the empty bed next to us. Thick freckles of red—betel juice or blood, or both—dot the washed-out wall on our right. In the center, Tabassum sits on her bed like a weak-legged puppet, chewing the rubbery hospital rice. She repeats over and over that our situation is better than that of others in the ward, better than both the sick and the healthy in Kashmir. She speaks to drown out what she thinks. When she finishes, she turns away and buries her face in mother’s scarf.

Had the internet and telephone networks been working in Kashmir, Tabassum could have heard mother’s voice at least once and perhaps then, her blood would have behaved and regained its life. The estranged microbes inside her could have made peace with her. But motherless, all she has of her is a woolen scarf she took the night she left for Delhi. It carries the lingering scent of mother’s hair, the wood of her cabinet, and the spices from the kitchen where she spends most of her waking hours. Tabassum holds the scarf to her every night, as she did when she was eight. I lay mine out on the floor, beside her bed, and put my arm over my eyes to block out the blinding lightbulb.

Above our heads, a loose, lifeless fan gyrates in confusing patterns, lamenting along with the patients. The sound of its misfortune worms its way into my head and sets off a streak of strange dreams. In one of them, I am six again, standing beside my mother’s bed in a hospital, barely tall enough to meet her dazed eyes. This time, her ward is flooded with sharp morning light. She has been rushed out of the operation theatre, and her body has shrunk to the size of a skeleton. Her bones have starved, and in deprivation, they have chewed hollow the flesh on her temples and cheeks. The needles that enter her wrists seem thicker than her arms and pull on her veins. She makes animal-like sounds in pain. She is my beautiful mother but, on that stretcher, she is only a bundle of bones and skin in green scrubs. When they lift her and plunk her down on the bed, her body moves like the innards of a cleaned chicken in a green plastic bag. Her eyes, watery and grey, are fixed on the ceiling, staring as if at something immobile, terrifying, otherworldly—something none of us can see. Tabassum’s blanket falls over me and I gasp awake.

It is 2 AM. Her fever has spiked, and her skin is burning to the touch. The nurses manage to bring down her temperature only after several freezing wet handkerchiefs are pressed to her body—one on her forehead, two on each foot. When her skin cools enough to allow her a few moments of sleep, she starts humming. I tuck her in and tiptoe back to the floor, back to another array of dreams until morning breaks again.

“Do you think you should speak to them?” My eyes flicker open and bulb-light floods right in.

I try to respond, but my words come out in a croak. “What?”

“The bed on our left. You should speak to them. They’re Kashmiris and might need help setting up.” Tabassum looks down at me from her bed, fresh as a daisy, crisp in her smile, no sign of fever or of the troubles from last night.

“How do you know they’re Kashmiris?”

“Because they’re speaking in Kashmiri!” She says, she has mother’s manner of twitching her nose while raising an eyebrow.

I press the aching knots in my shoulder and sit up straight. Bitter from the vinegar of my dreams, my mouth is parched. Expecting a nosy Kashmiri aunty on the other side of the curtain, I dust off my scarf, drape it over my head and knot it beneath my chin. Tabassum watches me.

“What?” I shrug. She looks away.

Mother would have given a customary “Hunh” and passed a few remarks—it doesn’t count if you are covering your head only when it suits you. But staring at me and disapproving of me in silence is the poison of Tabassum’s fangs.

That is when I hear Juicy. She is speaking to a patient—the woman on the other side of her bed. Juicy is trying to cheer her up. Though I can’t see her, she sits just a meter away, and her voice pierces my ears. The three holes in the curtain between us resemble two eyes and a mouth, and shift with every word she speaks. The patient that Juicy is talking to sounds eager to listen but too weak to respond. She is the one who has groaned for hours at night. Juicy keeps clicking her tongue, swallowing the drool pooling in her mouth as she begins to describe how she cooks her spicy baby potatoes for her famous Kashmiri dum aaelwe recipe.

“I always boil my aaelwe first. Then, take a knitting needle and not some stupid toothpick and prick the potatoes all over with that. Then, I fry them—for a long time, in at least one litre of oil.” She pauses, giving the woman a chance to take mental notes. “And then, after twenty minutes, they’re ready for the second round of frying. This is what most people don’t do. But if you fry them again, they turn out to be very, very delicious. Follow my instructions! And what if your potatoes are small, like our local Kashmiri aaelwe? Then it’s a different matter, sister. You can’t match that! You must pick yours carefully wherever you get yours from—they must be small and firm. Check with your fingertips, like this.” We cook a different recipe of dum aalwe at home, so Tabassum and I are equally intrigued.

“One litre of oil?” The patient on the other bed manages to mutter, catching up.

“Yes, one litre only, but that’s if you’re cooking for four people. And oh, you should never peel your aaelwe.” The mouth of the curtain erupts into a sarcastic laugh. “Only fools suggest that. Who does that! No flavour remains if you peel them.” She pauses and then raises her voice. “And remember, there is no dum aalwe without fennel, ginger, and chillies. The rest comes and goes, but these three are most faithful Kashmiri spices.” Tabassum nods, arching her eyebrows, impressed. “Hundred percent correct,” I whisper.

“And the Kashmiri saag, how is that cooked?” The woman interrupts, her laugh so voiceless, it sounds like dry air passing through hollow bathroom pipes.

Juicy proceeds to detail her recipe, making slurping sounds in between, asking questions and answering them herself. She then recommends places where the woman can buy Kashmiri saag in Delhi—the market, the hawker’s name, his phone number and a negotiable price. A few minutes pass before the patient announces that she’s not from Delhi, but from Pune.

Juicy sounds like a hyper-functional attendant. Her conversations with the people around her only pause when her son calls. The phone is on speaker, so everyone in the ward can hear both sides of the conversation. He’s a toddler. She congratulates him for not wetting his bed, for pooping the right amount, the right colour, in the right place. It sounds like he is showing her his poop in the potty chair. She kisses the phone screen in loud smacks, and he kisses her back, squealing.

Tabassum mouths, “What’s going on?!” She is tomato-red, struggling to contain a laugh. No patient in the ward seems to mind Juicy. The mood lightens, and the night’s claws loosen their grip. We hear a few curtains being drawn apart. The conversations brighten the ward and put the morning light to shame.

A man walks in then, “Tuhhe chuw’we Keashir?” He wears a blue checkered shirt and a shock of red hair.

“Yes, we are Kashmiris,” I smile back.

“We, too. I am Manan. My wife, Juicy, is admitted here,” he says with a gentle bow. Juicy continues talking on the other side with a newfound passion for bandhani dupattas. He blushes, bending his head as if apologising.

“No, no, we like her talking very much. Don’t worry about it, we thought she was perhaps an attendant.” I nod.

He raises his head and looks at Tabassum. “A sister told us a Kashmiri woman was admitted, next to our bed. I felt at ease—chalo, someone of our own. What brings you here? All well with the family?”

Tabassum smiles, shrugging, “All good.”

“Yes. That’s my sister, Tabassum. She has dengue and blood reports show some irregularities. We’ve been asked to see the head doctor, but they admitted us here instead.”

“Oh! Doctor Vignesh? He has an excellent eye! Think it might be serious? I hope not.”

“Umm. No, I mean we do not know yet, I mean, we haven’t met the doctor yet. We have an appointment soon.”

“Oh, nothing to worry about then. We will be here. Let us know if you need anything.” He bows his head again, waits for a moment, and disappears behind the curtain. I look around and it dawns on me that all patients surrounding us must have some kind of blood disorder or other, and many might have blood cancer. This is a haematology ward, I think. I turn to Tabassum and watch her watch me figure this out.

“How does that mean something bad is going on with me? Most patients here are under observation. Look everywhere, it’s a general ward. Don’t let your blood dry up worrying about nothing now.”

Now, years later, I revisit that moment hazy under the shadow of memory. I wonder if Manan had come to us that morning to share his ordeal, hoping I might ask him a few questions. What had brought him there? What about Juicy? Could we have helped? Had he slept well? Caught in the gravity of our own situation, we forgot to ask about his, and he didn’t seem to mind.

***

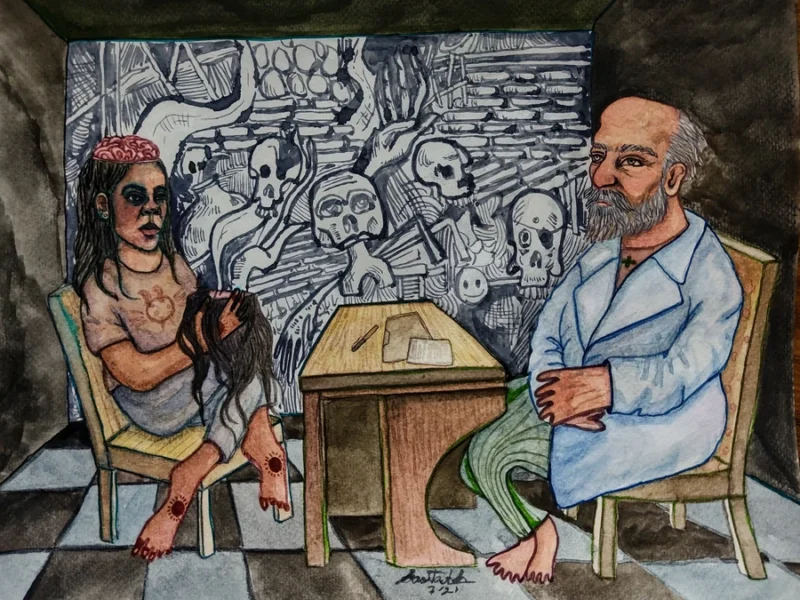

Slanting arrows of rain pelt on the green-tinted windowpane behind the doctor’s chair. His name plate reads Dr. (Brig.) Vignesh Dev in a curly cursive font. He glances up without pausing his typing on the keyboard. After thumbing through Tabassum’s reports, his mouth shapes itself into a smile—one that seems practiced, perfected over time, the kind an affluent city man might sometimes give to young bumpkins from war-torn mountains.

“Your friend?” He looks at me, his head tilted towards Tabassum. It’s not just the hijab—my skin is darker too; we hardly look alike. He nods when I said sister, having already placed us, and soon, there will be declarations of his own ties to Kashmir.

“So, your people generally have a low platelet count but this isn’t about platelets—it’s the low neutrophils in your blood,” he pauses, noticing Tabassum’s eyes on the photographs lining the wall. “I was posted in Kashmir for a decade before I retired.” There it is. “I mostly worked with the armed forces, but I am familiar with the health situation there. So…” he arranges his files, waiting for Tabassum to finish her detour, “We may need to do a bone marrow aspiration, just to rule out bad cells. This is precautionary—only a small percentage of results are worrisome.”

Tabassum looks at him, waiting for him to say more. There is a long pause. “Bone marrow test?”

“What does it entail? Is it a surgery?” I add. “Doctor, we don’t have any elders here with us.”

“It’s not a surgery. Only a small percentage of results are worrisome,” he repeats, his fingers on the keyboard.

We still have questions, but he has already rung the bell on his desk, and the next patient behind us is fanning his report over his face, his eyes on Tabassum’s seat.

We make our way down the staircase, it stinks of rotting banana peels, betadine, and urine. Frail, shrunken patients struggle down the steps. With the news of a longer stay at the hospital, old memories resurface—of a certain hospital in Kashmir, of wooden crates of winter fruits, butter bars and juice boxes, blood in bags, and urine on the floor. Tabassum holds my arm, and the touch of her burning fingers pulls me back to Delhi.

Back in the ward, Juicy is giving horoscope lessons to a nurse, sharing her WiFi password with the attendants of the patient on the bed opposite hers, as one might offer bowls of sugar and salt to neighbours in crisis. Tabassum, eager to speak to the family in the morning, is quieter now, irritated by the speed with which Juicy churns out words. I’m not particularly fond of Juicy’s voice—her happy flutter begins to sound like the frantic flurry of a bird trapped in a box—but she keeps us distracted. I long to be as free-spirited as her, to offer small joys in a sad hospital ward, to keep it together. I am certain Tabassum feels the same. The term “bad cells” echoes in my ears as though intoned by a hundred bloodthirsty mosquitoes. Elders at home often speak of children who are forced to grow up too soon when unforeseen emergencies put them at the forefront of battles they are not equipped to fight. I think of them, summoning their strength as I sign guardian consent forms and buy what looks like a needle for horses pinned to a T shaped plastic handle. This is to enter Tabassum’s spine the next day. I think of my overbearing family—too loud for hospitals, who are consulted for such decisions, who run errands, cook, clean, chat and care beyond their capacity, and who fill hospital wards with the jubilance of family get-togethers.

I barely get to sit by Tabassum. When I return to the ward, another set of papers, medicines and formalities awaits. Manan is seated on the floor by her bed, a blanket on his lap: “Tabassum passed out by the bathroom door. Nothing to worry about; my mother-in-law found her sitting there. Her fever was 101, but last we checked, it’s down to 99. She has enough medicine to help her sleep well tonight. You should get some rest too.” He hands me a blanket, bigger and thicker than my scarf.

***

At night I visit my first memory of Eid—a November evening that shows no signs of winter. Nobody cooks yakhni at home; the kitchen stove is cold, and my voice echoes through the house. Outside the JVC hospital where mother is recovering, a pheran-clad woman carries her lunch box and water bottle in a shabby rice bag; it seems as though she has spent a lifetime in hospitals. Mother opens her arms when she sees me, and we stand still in an embrace. The skin around her eyes have the color and texture of rotten apples, and her lips have a chalk-white outline. I sit on the windowsill the entire day, eating apples and oranges, gazing at life outside the hospital window. Occasionally, we talk. When mother giggles at my jokes, I feel my cheeks warm up. She says I must look after Tabassum while she is away and I nod. In the parking lot, a man, swaying his head, is pushing the dead body of a child into the back seat of his Maruti 800. I can’t hear anything through the glass window, but I know she is his daughter, and he is taking her home. She has been hit by a military truck at HMT chowk. I am eating my orange, watching. The car is too small; her legs refuse to fold, her body doesn’t fit. So he drives away with her two little pale feet dangling from the car window, her soles slapping against one another.

***

The next morning, we make a discovery at the haematology ward.

The attendants are asked to leave the ward so that the floor can be mopped. Standing outside the door, Manan walks towards me, accompanied by a woman, “This is my mother-in-law.”

“Asalamualai… ” I begin but swallow the word. Two long chains, dejhor, dangle from her ears. She’s a Kashmiri Hindu, not a Muslim. So is Manan, and Juicy.

“Waalaikumasalaam,” she responds. “Manan told me about you and Tabassum, and then I found the poor girl outside the bathroom, kyah ghom, Bhagwan!” She pulls me into a tight hug. It’s been months since anyone held me, and her arms feel both soft and firm on my back. Her hands are short and chubby, like mother’s, and she holds mine between hers as we talk. When I mention the town in Kashmir where I live, she asks of apple orchards, of autumn rains, and the famous copperware store by the banks of Wular. Apparently, the stream that cuts through our town in Kashmir, crosses her native village too. She asks about the internet in Kashmir and proceeds to tell me stories of her late father’s wood factory, his friend’s daughter’s career in medicine, their great-granduncles, and grandsons. She touches the mole on my chin and says Juicy has the same one. In the span of five minutes, she cracks jokes, grumbles about the hospital staff and offers food. She is truly Juicy’s mother, but she also acts like mine. The knots in my stomach start to loosen. When she holds my hand, I hold hers back.

Then she slows down. “My daughter is young, beta, she turned twenty-three last month.” My age. I blink. “She has a twenty-month-old back in Jammu. Bhagwan is testing our patience! Manan keeps me away from her because if I cry, it upsets Juicy, and right now she needs our strength. But I am a mother, how can I bear seeing her like this?”

“What do the doctors say? What is the matter with Juicy?”

Manan smiles ruefully, “Leukaemia. They are figuring out her stage, the damage, but it’ll all be fine. Just a few more tests. I tell Mummy ji not to worry. A doctor said a 95% chance of recovery is also possible, but she’s a Kashmiri mother, this habit of worrying needlessly will stay with them, even if they shift to London. They’re all the same,” he laughs. I nod my head.

She looks at me for reassurance. I hold her hand tighter. The tiles beneath our feet shine, and in their reflection, I see our three small heads plopped on six larger feet, as if there are no bodies in between. I walk towards Tabassum’s bed and stumble on the soapy floor.

***

A nurse explains the process of bone marrow aspiration—how the T-shaped handle of a Jamshidi needle provides a steady grip and pressure for the doctor to screw the hollow shaft into the dense bone tissue. How far, how long, must the needle travel before its trocar tip breaches the bone’s soft core—the deepest of materials in our bodies, the secret of bone marrow, the liquid life that makes our blood and makes us blush. “Can’t believe even a diagnosis can be so intrusive?” Tabassum is more curious than worried. “Do you think they can misuse my marrow and make clones of me? Is that how they make clones?” She looks it up on the internet.

Our grandmother used to say that a human is as fragile as the quivering film that forms on a cooling cup of chai. Here, in a hospital, life clings to the thinnest of these membranes—one wrong decision out of a hundred, and the balance shifts. And yet, outside, under the naked, brazen sky, we sail over a sea of uncertainties, climb mountains, jump off speeding airplanes for thrills, and live through a lifetime of heartbreaks, hard as stone.

Tabassum lies motionless on the bed after the procedure, her eyes on the ceiling. She shakes her head when I ask if she’s in pain. I tell her about Juicy’s family, about them being Kashmiri Hindus, about Juicy’s mother and her mole, and the stream our town shares with their native village. She listens but doesn’t respond. I tell myself it’s just the pain, that it has nothing to do with our far-apartness. But would she have been able to show her pain if mother was around? We haven’t spoken to her in a month ever since the last communication blackout, and we don’t know how everyone is at home. How do I take care of her? How do I fix this? Am I making this about myself?

If I were to recollect when and how I lost Tabassum’s friendship, I wouldn’t know where to begin. There are moments, I suspect, that may have pushed us apart, but when was it that we first stopped making peace after our arguments? As I said, I do not remember.

My fondest memory with her is of winters spent by a fire-howling bukhari, writing pages of bizarre Urdu sentences each day to perfect our handwriting. We learned to write with fountain pens and found ways to lighten the ink stains we left on mother’s white namdah. We would spit on the hot metal of the bukhari and watch the spitballs skitter and dance across its surface. There are other memories—rubbing our nettle rashes with leaves of the Obuj plant while chanting the Obuj song to summon the plant’s spirit.

We had secrets, the ones that never reached mother’s ears. Like when we used to put two spoonfuls of salt in Molvi sahab’s Lipton tea while carrying it from the kitchen to the living room. After repeatedly requesting mother not to add salt to his tea, he had stopped coming to our house to teach us the Quran, and mother had concluded that he might have had some sort of mouth disease. We’d slid our hands up under the gap of mother’s double-door almirah to steal two-rupee coins, then buy packets of the Khulja Sim Sim candies, and maintain a collection of its tiny plastic gifts. On Eids, under the pretext of greeting extended family, we’d sneak away to the world of Eid Fairs set up by the banks of Jhelum, where we spent our fresh and crisp Eidi notes on firecrackers. We hid our treasures in the attic of the house and made unbreakable kasam to never tell each other’s secrets.

But Tabassum grew quieter in high school. When I returned home after my first year of college in Delhi, brimming with gossip and stories, she looked at me—at my clothes and hair—with the same suspicion the neighborhood aunties did—a look I didn’t understand but was familiar with. She brushed me off whenever I spoke of our childhood mischief and seemed ashamed of the memories we had created together.

“I can’t stop worrying when I think of what we did to Molvi sahab, we have to apologise. He was trying to help us better ourselves and we drove him away. We should seek forgiveness from everyone we wronged before it’s too late.” When the opportunity to study in Delhi came up, she kept saying how she’d do it differently from me. Within the first month, she had said it twice—that this city wasn’t for her, that its chaos rattled her and left her with questions that threatened her sanity. She did not want to meet me, not yet. This was a week before she fell sick and was forced into my care.

***

The ward has a single TV mounted on the wall opposite Juicy and Tabassum’s bed. Juicy has tuned into a program showing the Shiv Tandav. On-screen, between the gold lined, salmon-pink Himalayas is a low-definition Shiva dancing in spirals, leaping from one peak to another. Juicy sings along in either Kashmiri-accent Sanskrit or Sanskrit-accent Kashmiri.

A new test report is hinting at trouble, but Juicy is louder, this time she is talking about her healer —a baba who has assured her that she will not die before she turns thirty-five.

“I wouldn’t worry much about dying, but my son,” the curtain mouth tells someone. “He’s too young. It was when he was born that the doctors found out something was wrong with me. My low count means I am sick, but it also means the infected blood is leaving my body to make room for healthy blood. Had he not been born, I would’ve never found out. My rajkumar saved my life.” Her voice carries a smile.

Their Kashmiri has words and connotations that ours doesn’t have. Tabassum and I have never heard a Kashmiri using the word ‘Bhagwan’ for God, and it sounds strange to our ears. “Bhagwan knows best and has the perfect plan for us. Bhagwan will sort out everything. Have faith in Bhagwan. Haye Bhagwan!”

The Kashmir that Tabassum and I grew up in didn’t have many Hindus—only stories about them, and those stories varied from household to household. In our imagination, they rang bells in temples, their women wore long gold chains in their ears, they were great teachers but favoured Hindu students in class. Places like Batpora bore their names. They built large multi-storied houses by riverbanks. They were said to be rich, but stingy. Most importantly, they had quietly packed their lives into trucks one night in the 90s and left Kashmir.

Now that we have them as neighbours for the first time, newer details about them keep surfacing. Their hands are soft and plump boiled carrots—just like ours. Their mothers fret like ours do. They too greet others with firm embraces, like Juicy’s mother did, without minding my salaam. They are as endearing to toddlers, as half-witted, as cursed, as entangled in other people’s sorrows as us.

They are almost like us, and in the big city of Delhi, it feels as if they are family.

Perhaps Juicy, too, in her imagination had known us and our kind in limited details. That evening, after murmurs we can’t decipher, we hear Juicy’s mother whisper to her, telling her not to say nonsensical things and reminding her not to assume too much about a Kashmir she has never lived in. Once, she tells her, sweet relations existed between “us” and “them.” Perhaps Juicy’s mother is right or perhaps she is mistaken, and the opposite is true: people differ in more ways than they are similar. That, cracks widen into gorges, and mountains break away from the earth. That, seams and silences are often irreparable.

I doze off. A few minutes later, there is a rustle on the bed.

“Aapi,” Tabassum says without turning her head towards me, still as a lake. “Can you put mother’s scarf by my pillow before you sleep? It’s next to my leg.”

I walk up to her bed. Thick teardrops tremble in her eyes. I bring her the scarf, press a kiss to her cheek. I want to hold her head in my arms but she’s waiting for me to leave.

“Is your back hurting?” I ask, she stiffens, turns into a stone in my arms. “I’m not mother, but I’m here for you. The reports will be fine. And if they’re not, we have so many people on our side. We don’t have to rush. We can figure out a way to go back home or get father here. Or mother, if you’d like.

Every time I visited home for vacations from Delhi, Tabassum would say, “Aapi, finish your studies and return to Kashmir. Each time you come home, you keep pointing out new issues—this is wrong with Kashmir, that is wrong with Kashmir. This is how things should and should not be done. We can’t keep you with your antics. I sometimes feel like I don’t know you anymore, that I don’t have a sister anymore.”

I stayed back in Delhi after college. I hadn’t loved the city, but she was right—the longer I stayed, the more I found myself at odds not just with home and Kashmir, but with the world itself. Most people my age, in Delhi or elsewhere, seemed to go through the phase of picking a fight with everything. We were at war with the world, with everything at once. That’s what some classrooms did—through a gradual and a grueling reading of the world, through dissecting and discussing it, some classrooms made you think, question, theorise and suddenly, nothing looked the same: what had seemed beautiful now felt cruel; what had been pride now felt like ignorance; what I had been taught as the natural destiny of life, now seemed like roles imposed upon me. The process embittered you, but it also made you hopeful. It gave shape and meaning to your life. When you finally spoke up, it was as if you were meeting your own voice for the first time.

But this finding of voice also left me exhausted. I began to feel disillusioned with that life. While we were consumed by the frustration of perfecting our “personal politics” in the streets, we failed to uphold them in our relationships. We began to see the holes in the theories we had once believed would save the world—how they were narrowly and selectively applied. Week after week, we led protests and candlelit marches for women’s safety in Delhi, and week after week, we were told that the news of sexual violence coming from Kashmir was hard to trust, that the numbers could easily be fudged. We discovered, firsthand, the joylessness and misery that came with categorising people into boxes after boxes after boxes. We grew tired of maintaining shaved limbs and having opinions ready for every situation without getting the chance to think, question, reflect or argue. One Ladies’ Night, I looked at my mascara-clad eyes in the bathroom mirror and thought, I don’t like this look on me anymore.

But at home, time moved slowly and struggled to keep up. To Tabassum and mother, I was no longer a good sister and a good daughter—I had a tez tabiat. I never returned to covering my head. But I had found what I believed was the capacity to think and define the idea of a good life—a life that was slow and solitary. There was a job, but fewer socials; a faith, but no urgency for penitence or exaggerated reactions to childhood ‘sins’. There were fewer friends, but better conversations—ones rooted in empathy and curiosity rather than judgement. Tabassum and mother thought I was just bluffing my way back in but that wasn’t the case. In breaking, finding, and reassembling pieces of myself, in making my way into the larger world, I had distanced them, and they had grown closer to each other and to Allah Ta’aala.

***

At dawn, a block of powdery light slips in through the ventilation window, barely touching our corner bed. Tabassum sleeps on one side. I gather my limbs, climb the bed and lie down next to her. The curtain shakes a little, and Juicy’s hushed voice floats over the morning light. She is humming a song a flower sings to a bud, a lesson on what living must look like: borrowing someone’s pain, kindling love in your heart for the other, burning up to fulfil the desire of spring. If you do so, the flower says, you bloom through their lips as smiles. Dear Juicy, I think, and find myself unable to put a face to the thought. I sidle back to sleep.

In my morning dream, mother is in her garden. She sits on her haunches with Tabassum and Juicy next to the dwarf apple trees. Each branch holds an arrangement of ruby Gaala Must, the sweetest of apples, that look like banquets of blood roses. Behind them is an undulating wave of hills with unusually bright spots where the clouds draw apart and let the skylight in. Deodars with straight spines stand in neat formations—land’s own soldiers who exhale firewood smoke from their crowns like bored grandfathers. Under the apple trees is a lake of pumpkin vines with arm length leaves. Hidden beneath, are the many inflating wombs of the pumpkin plants. Juicy and Tabassum walk among them, careful with their feet, trimming the young foliage of the plants, their large butter flowers, and their delicate tendrils.

The nurse walks in and tells us that Tabassum’s results have come. Outside, the thick woolen clouds are thinning into a threadbare sky. Juicy’s mother appears from behind the curtain, “Let us go with the nurse, we will check it together,” she pulls my arm. I fail to process a single word on the page until the nurse tells me. “Normal. The test is normal. She is healthy, the doctors have seen the report, and she will be discharged in the next two hours.”

“Mubarak, bodh mubarak!” Juicy’s mother kisses my forehead.

I head back to the ward and hold Tabassum in my arms. My shoulder is wet with her tears. It takes us less than an hour to wrap our things up. Packs of juices, bills, handkerchiefs, phones, leftover medicine, a file full of prescriptions and reports, all of it fit in one medium-sized bag. I dust off Manan’s blanket, fold it and keep it on one corner of the bed. When I walk to their side with the packed bag hanging by my arm, he looks perplexed, “Are they shifting you? Did the reports arrive?”

I nod my head and place the blanket into his arms, “Where’s aunty? Did she not tell? All reports were normal. The doctor believes it might be her body reacting differently.”

“That’s wonderful! Mummy ji is in the canteen for breakfast, I haven’t spoken to her yet. So, you would be leaving then?” He asks as if wanting to hear a no.

“Yes, we are, I hope you leave soon too! I…I thought before we left, we could greet Juicy once.”

He looks in her direction. I follow. She is sleeping with the blanket over her face. An array of machines crown her head. She looks tiny, it is hard to believe that the loud, hearty voice that had filled up the ward came from such a small body. “She just fell asleep. Last night was rough for her, hasn’t been able to digest any of what she ate. We will have to start chemotherapy; the reports have suggested. Perhaps we should let her rest, she just went to sleep…”

“Yes, yes of course! I would have loved to say bye to aunty. But, alright then, take care Manan!” I smile, turn around and walk towards Tabassum. She smiles back, holds my hand and we leave.

Outside, the water has receded, and the August sun is where it is supposed to be. “There’s something very wrong about putting all sick people together in a single building on the pretext of treating them, don’t you think?” Tabassum shudders. I throw a last look at the hospital building and its tinted glass windows. One behind which the doctor and brigadier Vignesh types furiously on his keyboard, the one by which boats of clouds anchor at night and drift away with the morning winds, and the tiny window by whose light Juicy, with a mole on her chin, sings and chats endlessly to old and new people, hoping to live up to at least thirty-five.

The rickshaw pulls us away and with each passing minute, the world we have left behind for a few days, returns to us. The trains, the autos, the flood-soaked walls and hostel wardens. I go back to worrying about the internet in Kashmir, and Tabassum about the length of my hair. My nightmares pause and I forget again about mother’s hospital visits. We partake in the banalities and quibbles of life outside the hospital as we had, dancing to our tunes in our self-built glasshouses. Old screens in metro stations tell new tales about the world and the winds move ships in different directions. By the time it is August again, another winter has overstayed in the Northern Hemisphere. Uprisings in the East have triggered geopolitical speculations in the West. The world continues to race forward as new records break and compete to be the next big headline. And the year after, and ever since that day, no news has remained breaking for long enough to be grieved. Previous records are broken every day: of rainfalls, temperatures, hospital admissions and closures, of collateral damages and loved ones lost in the oceans, of fossil fuel reserves, carbon emissions and market prices. I forget most details too. But every now and then when a loved one needs to visit a hospital or someone makes a remark about the mole on my chin or remembers Kashmiri Hindus, Juicy and her voice will return to me. It is then that I spend my nights awake, wondering why I never spoke to her, never took her number, never shared a story, but most of all, why I hadn’t pulled back that stained white curtain to give a face to her voice.