I think I experience panic attacks, but it’s hard to be sure—a panic attack is a difficult thing to pin in place. There are thousands of accounts of them: sometimes people report screaming, or fainting, or hallucinating. While common threads can be collected and wrapped up in neat packages—shaky shoulders, shortness of breath, to name examples—no two panic attacks are exactly alike. One woman

I have never fainted. I have never considered that my heart might be failing in any sort of clinical way. But still, I am certain that something is happening. Increasingly, I find the something fascinating. My body curls one way, and my brain seems let off a sort of leash. “Why would a brain do that?” I wonder. But then, animals do all kinds of things science cannot explain. Maybe it is foolish to try to understand.

Maybe we are all somewhat compelled to draw what drives us mad.

There is a possibility, though, that art can explain some of it. John James Audubon, who was deeply fascinated with birds at an unusually young age, found very little language to describe their mysteries, but painted them obsessively in what can only be described as a distinct and unprecedented voice. He told people more about the science of birds through his

My hypothesis is that some of this will be clear if you can see it. This is not to say that anything will be solved. The compulsion is not to cure; it is merely to mark that the thing (the thing I am calling “panic attack”) has occurred.

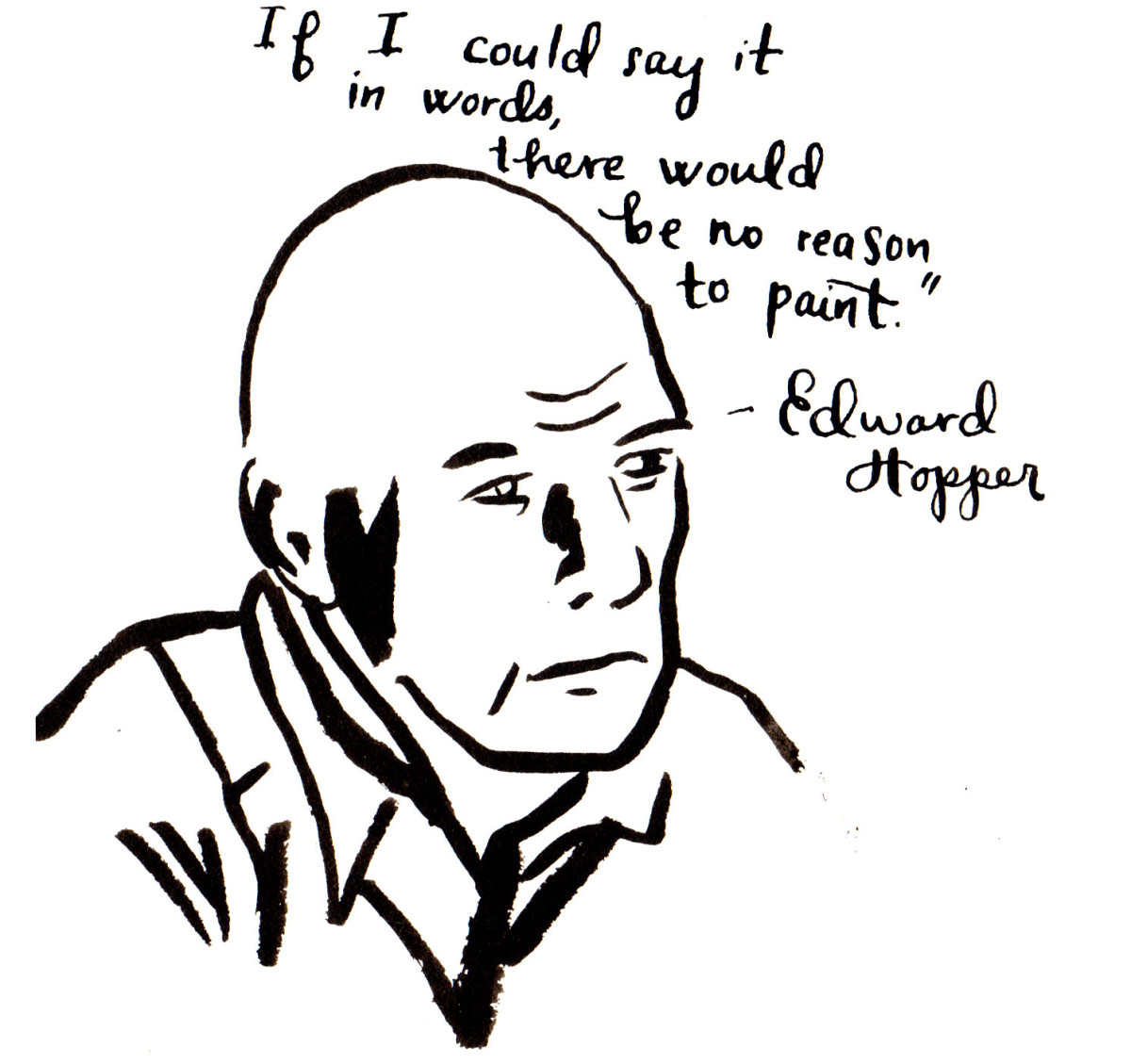

Fig. 1

I am in my room. The room is a normal room. The walls are white. There are two shelves, and the shelves have books. The patches of plaster and caulk on the wall explain that the landlord doesn’t care very much about this house; he knows he can rent it out for more than it is worth because the neighborhood is gentrifying, so repairs need not be loving or consistent. There is a bed. There is a closet.

I am on the bed, and nothing has happened to me [A]. This is part of the mystery. But although nothing has happened to me, my face transforms just then; it crinkles up like something red and silk. My shoulders hunch; my right arm twists out in front of me and forms a claw; I grab at nothing. The sounds are like crying—my eyes well up, my cheeks get wet, my face starts to shine—but you wouldn’t call it crying, because it is entirely indelicate and features more heaving and crashing. This is what it looks like from the outside; an observer would call it melodramatic, absolutely. It appears too gigantic to not be fiction.

Maybe you didn’t know this, but sea anemones fight. An anemone is that knot of pink-and-blue nerves that fixes itself to rocks and sways like ocean wheat; that kite-sock of tentacles you learned to press your finger into when you went to the tide pool, so you could safely see what it looked like for an animal to be afraid.

A fight between anemones takes hours. They move like molasses, but more. From the outside, where the world is moving in regular time, it looks like a screensaver or a lava lamp. In there, it is unthinkably ugly and violent.

From the inside of my body, this indelicate crashing feels just like that—a swirl of nerves in perpetual head-on collisions The anemones push through my chest, like in a comic book about radioactive parasites [B]. They strip each other’s skin away, like polyester being transformed to ribbon [C].

The podcast Radiolab recently aired an episode called “

Jaime’s mother reported that the first words out of Jaime’s mouth after she “came back” from one of her manic episodes were, “Mom, it’s not me.”

A similar story ran on the “

The first time a doctor used the word “bipolar” to describe the symptoms of my own mental health I was sixteen. I sat on a sterile medical table, crying into my hands because—why? I don’t remember why. The thin paper wrapping the table shook under my weight. My doctor—a bookish woman with mousy hair and gold-rimmed glasses way too big for her nose—said, terrifically gently, “It sounds to me like you may suffer from bipolar disorder. We could look into it more, if you wanted.”

I told her that no, I did not want to look into it more.

I had not described hallucinations to my doctor. I had not described manic episodes where I stood on top of buildings and came out of my body and believed I was invincible, or having chats with the devil or God or any of their ilk. Those were not things I had experienced. I had simply described highs and lows. I had described feeling very happy one day, and incapable of getting out of bed the next day. I was unable to identify triggers for the shifts, and so my doctor, who knew a little about bipolar disorder, thought she had solved the mystery.

I did not want to look into it more because I did not want to have bipolar disorder. That sounded like something that would follow a person around. It sounded like a permanent kind of flaw. But I kept the word in my pocket, and took it out when I was sprawled out on the bathroom floor screaming and crying because—why? I never knew why, exactly. I would be sprawled out on the bathroom floor crying and I would take the word “bipolar” out of my pocket and put it in the palm of my hand and think, “Maybe this is my flaw. Maybe I am broken in this particular way.” Something about having a name for the thing was intoxicating. I wanted the name, even if I was the sole person who got to know it.

Years later, I decided to nail this “bipolar” word in place. I saw therapists and psychologists who said, “Yes, you might be bipolar, but it’s hard to be sure.”

It was hard to be sure because bipolar is complicated. There are several types of bipolar disorder, including Bipolar I (like Jaime and Giulia have), Bipolar II (less severe, but still), and Cyclothymia (not so severe—your basic extreme highs and lows). Sometimes I felt lonely and sometimes I felt excited. There were times when I needed a lot less sleep than other times. I certainly talked incessantly from time to time; otherwise, I was prone to apathy. I could check all of those boxes—bona fide symptoms for this particular disorder—confidently. But: I had not ever spent so much money that I couldn’t pay rent. I had never missed work because I was too depressed to go. So those boxes stayed empty. My flaw remained ambiguous.

My mother told me once that the field of mental health is mostly fabricated. People want to have something wrong with them, because just this simple business of being a human is more painful than any of us can stand. If it is so painful just to be alive, she said, maybe there’s some comfort to be found in the acknowledgement of a defect.

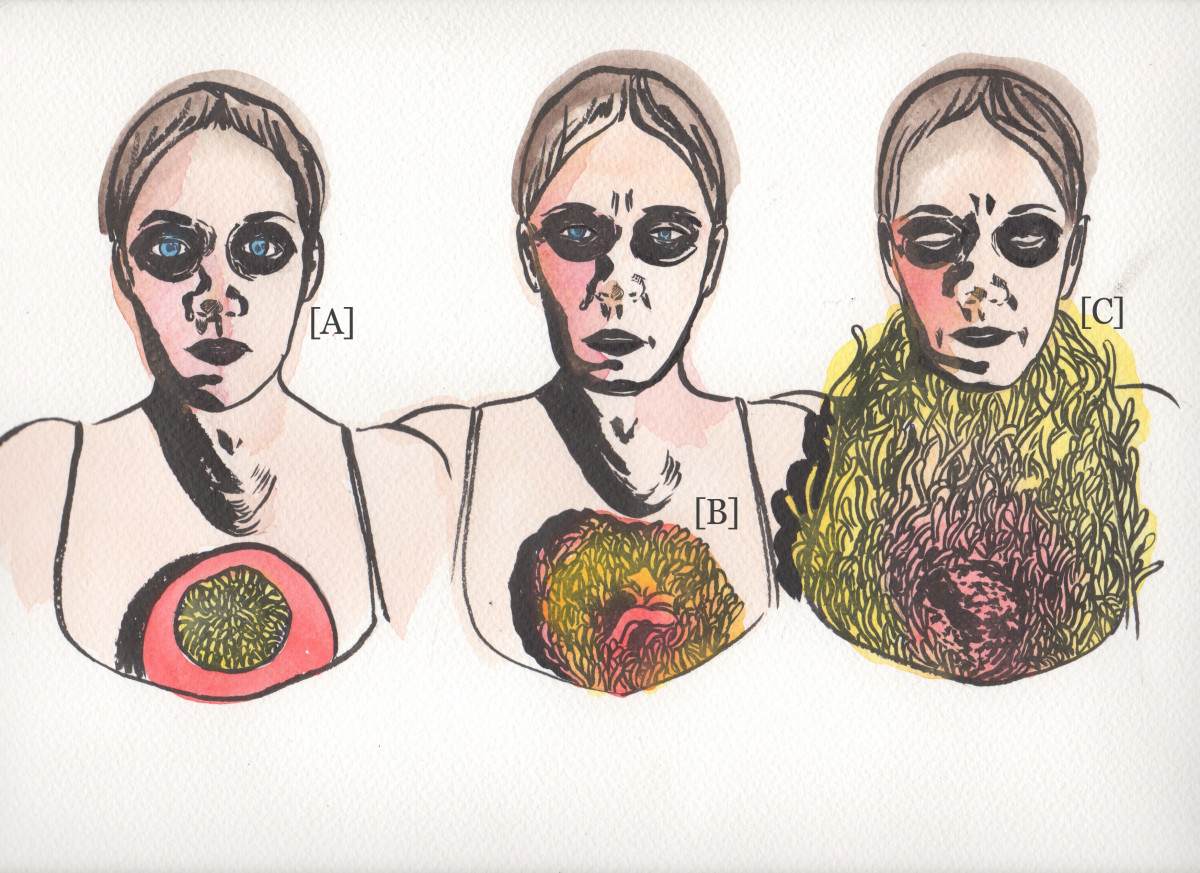

Fig. 2

Someone sticks a pin into the center of my chest. They stick a pin into the center of my chest and then slowly move the pin in concentric circles, quietly outward, so that the hole, which was once pin-sized, can stretch. Now the hole is the size of a fist [A]. Not only is the hole the size of a fist, but also it is a sort of vacuum. It is sucking in dark air; gulping at the atmosphere. As the fist-sized hole gulps, it grows. Now it is the size of a basketball [B]. My chest is barely the size of a basketball, but there it is: a gaping, basketball sized, vacuum-sucking hole right in the middle of my little human chest.

The hole is incredibly painful. I bring my knees up to my chin to meet it, as though maybe, if I could bend at just the right angle, I might cram my knees into the ever-widening cavern. The space wants to get filled up. So I move my knees as close to my chest as I can, but they do not fit. The hole gets bigger. Now it is sandwiching into the warm hinges of my armpits. This is incredibly painful, I think. It seems to last forever — because time stretches out when you are suffering — but in truth, it must go on for an hour or longer. Emotionally, this is days.

I try to imagine the hole that is still growing in the center of my chest like a thumbprint.

The hole now has its own agenda, and I try to move so that it might be satisfied. Nothing is working. To distract myself, I think about the Great Blue Hole in Belize. I’ve never seen it, but I read a children’s nonfiction book about it once when I was stuck at a library in a rainstorm. It is 984 feet across, and 410 feet deep. I can’t imagine how big that actually is—those are numbers that are only numbers to me; not distances I can truly understand. The pictures are all taken from the sky, and they make the massive, impossible hole look like a thumbprint. I try to imagine the hole that is still growing in the center of my chest like a thumbprint.

The Great Blue Hole in Belize contains spectacular, scary species of fish which all love the dark. There are Midnight Parrotfish and Caribbean reef sharks and bull sharks and hammerheads. It is not a place for the thin-skinned or the weak-stomached. SCUBA divers die all the time while doing what they love the most.

My own sinkhole is now so big that I no longer contain it; rather, it has swallowed me up [C].

I want to say I remember the first time this happened, but I don’t. When you’re very young, it’s difficult to know when something qualifies as disorder. Trevor Handley (not his real name) rejected me over the phone when I was fourteen, and I remember thinking that I was sure that I had never been that sad before. I took my clothes off and lay on the navy blue sofa in my dad’s study and watched a commercial for diamond rings. I thought, “No one will ever buy me a diamond. I’ll never be in love.” I cried for hours, actually hours, not what seemed like hours, but real hours, curled up on my dad’s sofa like a shrimp.

I fell asleep with the TV on at four in the morning, and had a dream that I was being “castigated.” That was the word in my dream. “Castigated,” in the dream, meant that you were placed in a jar full of clear liquid and drowned. Then people walked by and looked at your corpse in the jar and said things like, “Oh, what a shame.”

I wrote down the dream on a napkin and placed it in a box to remember my sadness. It seems strange to me now that the sadness was something I wanted to preserve. But I think I saw something beautiful in it. I felt like my suffering had matured, and now I experienced it as an adult, whose pain left scars. I listened to Alanis Morrisette with dawning understanding.

That was not a panic attack. The attack part was missing. This was wandering into the cave of a bear and harassing it, which all of us inevitably do when we fall in love.

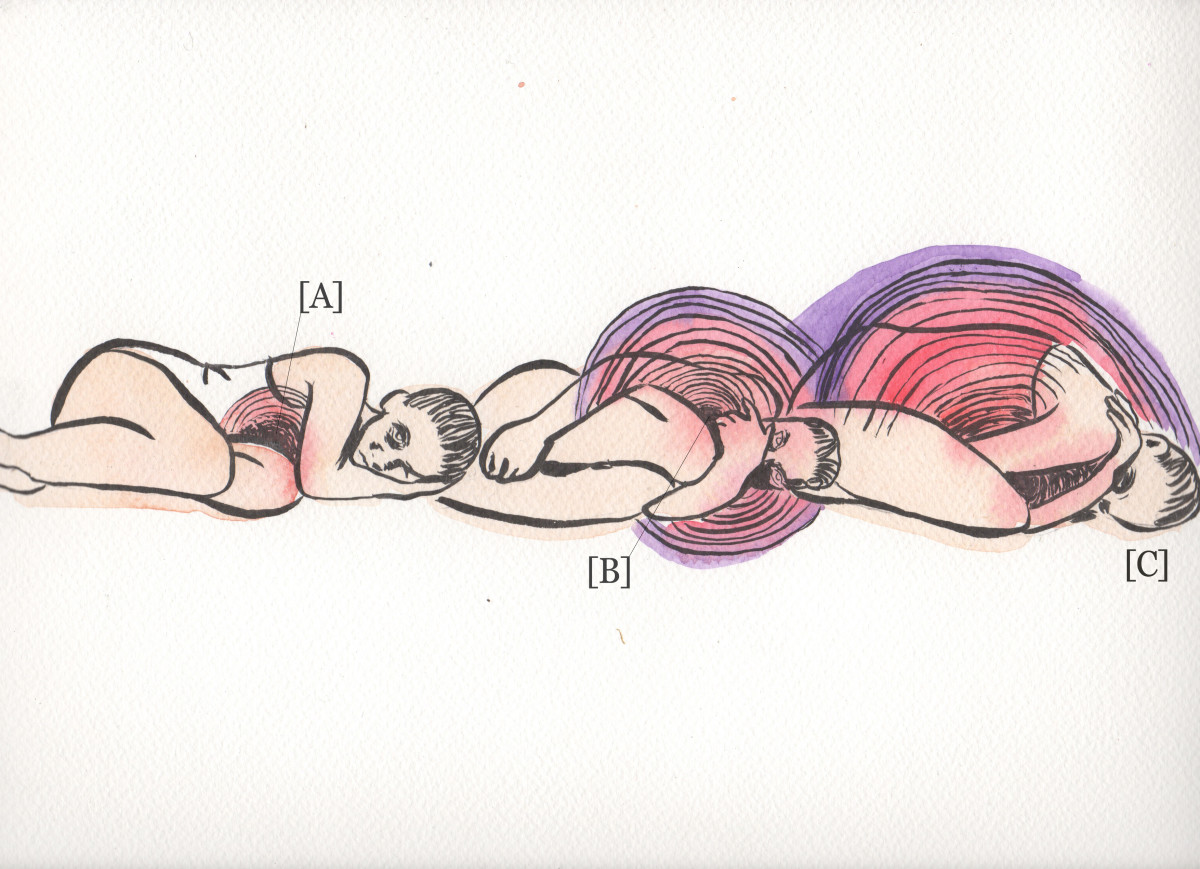

Fig. 3

I am smaller than normal [A]. In real life, I am what a lot of men have called “a solid woman”: I am tall and when I sit down my stomach doubles over on itself so you can’t see my belly button. But now, I am smaller than that; the aggressive beat of a bird’s wings too nearby could topple me; and so I try to get down on the ground, because that is what you are supposed to do during an earthquake. (An earthquake renders us all tiny; a tangle of seeds in the sweaty hair of a lion.)

As I cower on the ground, a larger version of myself appears [B]. She is angry with me. I have really fucked up her life. She stands over me—nothing could knock her over—and she bellows, with the great swollen pipes of a church organ in the middle of rural America. She stands over me and enumerates the ways in which I have failed her. There are plenty. She reaches back in time and recalls things I thought I’d permanently buried.

And then another larger version of myself comes to join her. Suddenly, there is a chorus of them [C]. Or, a pack [D]. Most carnivorous animals hunt alone, but there are exceptions. Wolves are most famous for it. Like storm clouds quietly swallowing the sky, wolves surround their prey, leaving no hope for escape. In Norse mythology, there is a wolf named Fenrir who is strong enough to break bonds placed on him by the otherwise-impenetrable gods; his offspring are fated to eat the sun and the moon.

The word “melancholy” comes from the Greek melas (dark, black) and khole (bile). Ancient Greek and Roman physicians believed that any physical ailment or mental deficiency came from a surplus or paucity of one of four humors, the bodily liquids blood, phlegm, yellow bile, and black bile; every individual was thought to have a unique humorous makeup, and diet and lifestyle could affect its balance.

Black bile was associated with our modern understanding of depression or mental illness. A surplus of this humor made one melancholic, which was considered a mental and physical disease. Hippocrates assigned all “fears and despondencies, if they lasted a long time” as symptoms of melancholy in his Aphorisms. If someone could not be cured of her melancholy, she was thought to be possessed by a demon. Of course, this is all wrong. It is almost silly.

We have more words for all of it, but people, it might be argued, are the same as they ever were.

In the nineteenth century, what had been known as “melancholia” was renamed “major depression.” Now there are lots of little branches of this “major depression,” which qualify as minor depressions, or as major subsets affecting minor populations who suffer from major depression.

We have more words for all of it, but people, it might be argued, are the same as they ever were.

In 2013, Dr. Christine Montross, a psychiatrist, published a book called “Falling Into the Fire: A Psychiatrist’s Encounters with the Mind in Crisis.” The book is mostly a personal record of her early years of practice, full of detailed stories and lingering questions. The main takeaway from this book, which spends most of its time in hypnotizing anecdote, is that diagnosing mental illness is unbelievably difficult, and always controversial. “It’s difficult to separate illness from context,”

The New York Times recently ran an editorial by philosophy professor Simon Critchley on his late teacher and mentor Frank Cioffi, who held a particular dislike for Freud and his effect on the popular culture of the twentieth Century. Critchley

Cioffi’s problem with Freud—and with many scientific obsessions, it would seem—is that science can only do so much for man. People want to believe that everything can be explained by logic and experimentation, but it can’t. “There is no theory of everything, nor should there be. There is a gap between nature and society. The mistake […] is the belief that this gap can or should be filled,” Critchley writes.

Maybe I experience panic attacks. Maybe I do not. I can’t find the box for my particular disorder to fit inside. The above, therefore, is ultimately no more than an act of translation. On the other hand, it is no less.