I.

My father is profoundly deaf. He has been so since birth, like his brother and father, like many others on his side of the family. He does not read lips, he communicates in American Sign Language and written English. Never in his entire life has he heard any sound whatsoever, nor does he particularly want to—his sensory experience of the world is the same as it has always been, he points out, and he has no desire to attempt to change that, through cochlear implants or magic wands or otherwise.

Among the things that have transformed his experience of the world, however, is the invention of closed captioning, the arrival of which in our household was as momentous for him as, say, the dawn of MTV was for my sister and me. His TV tastes run to sports, the news, a lot of action movies, a lot of comedy, especially physical, slapstick stuff, dramatically expressive stuff that you can get the general drift of without sound. For a while our family had two televisions, side by side, one muted and captioned, the other with the volume up (my mother, my sister, and I are all hearing) and a wordless screen; and our split focus shifted back and forth between two channels, two modes. Captioning explained things my dad had previously guessed at—here, now, revealed, were whole passages of dialogue surrounding a gag in a rerun of I Love Lucy he remembered from childhood; here, spilling across the screen in black-barred type, was some typist’s interpretation of a sitcom sound effect—ZRRBRRTTT, the caption would bleat—or what might have otherwise been alluded to—[KISSING SOUNDS]. Subtle moments missed in other films were suddenly illuminated and made comprehensible; plots were clarified; gaps were filled; mysteries were solved; the visual world was explained. Was it made larger, I have later wondered, or smaller? Was the reveal so drastic and great each telling now existed as two separate stories, with two separate meanings?

II.

There are multiple ways to approach Alec Soth’s Songbook, just out from MACK, which sits in your hands like a slightly oversized hymnal or collection of sheet music, its dimensions ostensibly deliberately askew from either of those things. The pea-green cloth binding, the practically floral typeface of title and photographer’s name, the bit of notation and lyrics printed on the back, from Howard Dietz and Arthur Schwartz’s “Dancing in the Dark” (“We’re waltzing in the wonder of why we’re here / Time hurries by / We’re here”) with the direction slowly and with much expression—all point at, of course, the Great American Songbook, the canon of twentieth-century pop standards, by turns hopeful or morose, swooning, hokey, expansive. “Georgia on My Mind.” “Moon River.” “All of Me.” “Santa Claus Is Coming to Town.” The kinds of songs that, at least once upon a time, everyone knew by heart.

His photographs may not exactly be the songs sung by lovesick girls waiting on porch swings for their soldier beaux, but they are of that world.

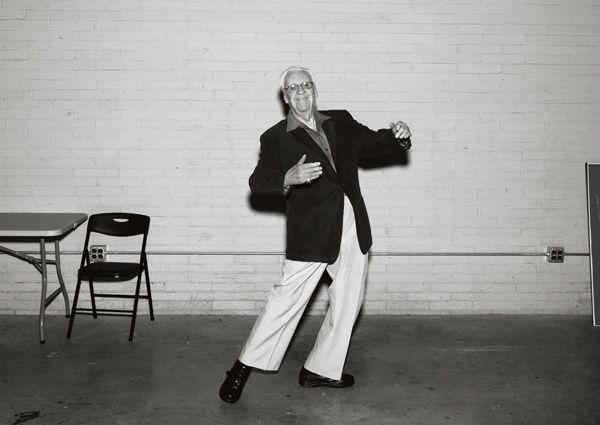

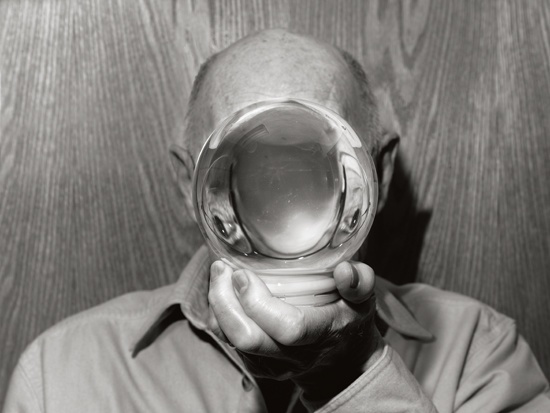

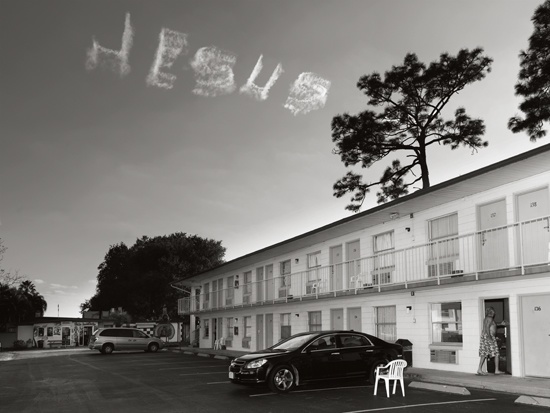

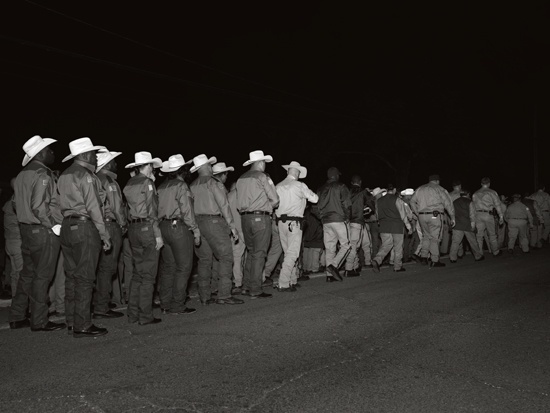

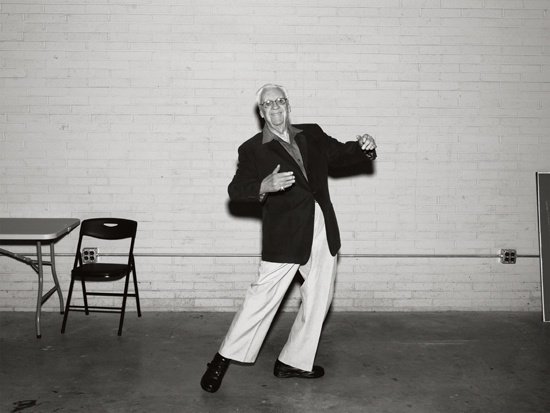

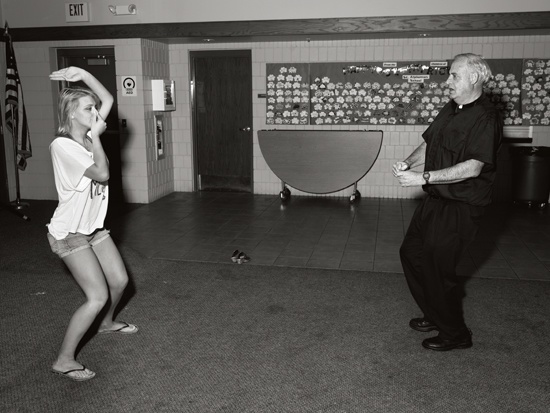

Swollen, marshmallow-white clouds puff out over the rooftop of an abandoned motel as if on the verge of engulfing it, and if that sounds a little pearly-gates heavenly, a few plates later, another motel: the word JESUS has been skywritten overhead, perhaps just escaping the attention of a patron clad only in a pair of long printed shorts, flip-flopping back into his room maybe to fetch a beverage to enjoy in the standard-issue white plastic chair he’s dragged out into a parking space. (Will JESUS still be legible when he returns? Will it have partially evaporated, vanished, simply, to US?) There are recurrent flip-flops, recurrent motels, recurrent churches. In what appears to be a church basement, in a strange yet chaste scene, a teenage girl dressed in denim cutoffs and flip-flops boogies some several feet away from a priest wearing shirtsleeves and a backwards collar. In another photograph, in some other room somewhere, a smiling man dances all alone. There are funny moments, moving ones. There are recurrent, somber processions: a family in orthodox dress walking along a roadside at night. Texas rangers filing in line for an execution. There are recurrent lonesome rooms so lonesome that no one is in them; there are recurrent lonesome structures looking very much in danger of being swallowed up by the natural world: swarms of kudzu preying on a farmhouse. That cloud-surrounded motel. Verse, chorus, verse. There are recurrent lonesome figures inhabiting vast-seeming scenes, fields and woods and bedrooms. The fields become larger, the figures smaller. Slowly, and with much expression.

Those very familiar with Soth’s work will no doubt recognize many of these from another, particular project, but more on that in a minute; for now, consider Songbook as songbook, photobook as songbook: Soth placing himself in the role of yesteryear composer. His photographs may not exactly be the songs sung by lovesick girls waiting on porch swings for their soldier beaux, or by improbably tap-dancing fellows making their way down rainy streets, but they are of that world, and certainly they are of those who exist just on its borders. There’s a musicality not just in the subject matter but in the visible yearning for connection and communion that is palpable in the most solitary of these photographs, even if it’s simply a hand tossing an object to another hand or that kudzu, creeping ever closer to the front porch.

They are of the world of Soth’s previous photographs and books, like Sleeping by the Mississippi, Niagara, Broken Manual, The Last Days of W, and of the books he publishes under his imprint Little Brown Mushroom, all of which have an abiding interest in the way words and images work together—or choose to work alone. “I’ve never necessarily loved the two together,” Soth told me recently on the phone. Songbook isn’t overly wordy, but here and there, throughout, are smatterings of verses from the Great American Songbook lyricists—Cole Porter, Johnny Mercer, Sammy Cahn—subtle, but certainly suggestive. Soth has muted the words that in another life once accompanied these photographs, replaced them with sparse, wistful, and earnest lyrics. Out of context, their meaning becomes larger and ambiguous: you can imagine any number of stories happening here.

“Well, I cheated a little,” he says. “I needed to nudge the interpretation away from the literal side of the story. Muting the words felt great in many ways. I was freed to bathe in the music of it. Like, I can just cruise on it. I can just be a photographer. It was liberating.”

III.

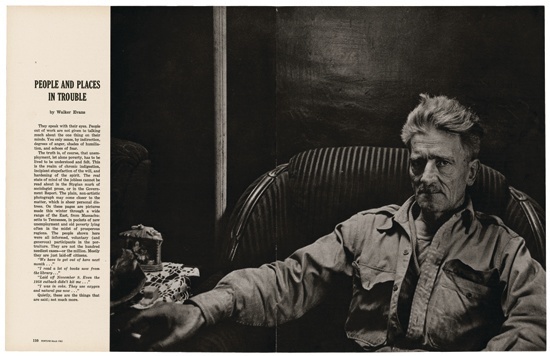

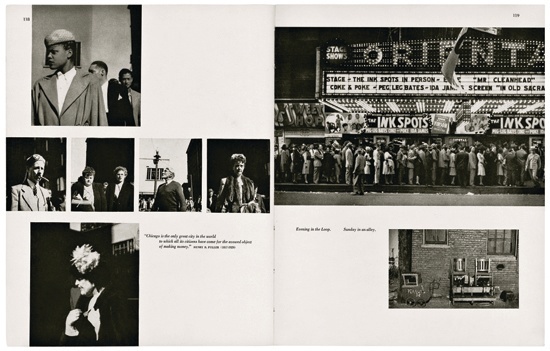

Walker Evans was one half of photography and writing’s storybook romance—if a not perfect one (and what could be?) then at least the one on which all others are based: Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, with James Agee. The book was as radical for what it did not do—it went against everything one is taught since reading “picture books” as a child, rejecting the assumption that images exist to directly represent words—as for what it did do, which was to tell a story in which images and words were equals, but did not necessarily have a literal connection. Charged with that dual responsibility, each was free to wander, while also bound to respond to the other, in order to achieve a kind of narrative balance.

And so, like a classic vaudeville duo—where Agee strayed wild and eccentric, long-winded and rhapsodic and besotted and even weirdly erotic in his portrayal of a few sharecropper families in Depression-era Alabama—Evans essentially played the straight man, making photographs in the pure, declarative mode that has become his legacy. Agee lived with the families, immersing himself in their lives to the point of fantasizing about them; Evans apparently took a room in town. His collaboration with Agee began in the model that magazine assignments generally follow today—photographer assigned to writer—but became a kind of finishing of each other’s sentences, in the way of old married couples. Set to Agee’s words, Evans’s photographs are direct and affecting; the book that came out of what was an assignment for Fortune (yet never published by the magazine) was fact and fiction, narrative and projection. Let Us Now Praise Famous Men defies convention and length and genre and tone, risking and failing and succeeding and surpassing all at once. It is the utterly weird model to which later collaborations of writers and photographers continue to answer; not just documentarians, but all kinds of storytellers.

Evans had wanted to be a writer himself; he majored in French literature; he wanted to write like Joyce or Flaubert, and eventually, he would become his own Agee or Faulkner.

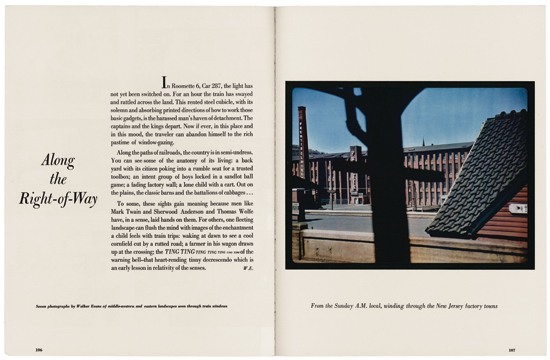

Evans’s other collaborations are part of the focus of David Campany’s recent Walker Evans: The Magazine Work (Steidl). With Agee, for instance, he clandestinely photographed their fellow passengers on a cruise to Havana for the story “Six Days at Sea,” which was published by Fortune; to accompany a story about William Faulkner running in Vogue, he was commissioned to photograph the Southern landscape of the novelist’s fictional world. In a kind of call-and-response move, Faulkner, in turn, would be motivated to write a short story based on a photograph by Evans that he had seen, of a graveyard; “Sepulture South: Gaslight” would later appear in Harper’s Bazaar.

Initially, Campany writes, Evans had wanted to be a writer himself; he majored in French literature; he wanted to write like Joyce or Flaubert, and eventually, he would become his own Agee or Faulkner, writing, in florid prose, the stories he photographed for magazines like Fortune and Time. “Photography seems to be the most literary of the graphic arts,” he once said. It was a sentiment shared by other photographers after him, like William Gedney, whose photographs of the Cornett family in rural Kentucky have much in common with Evans’s and Agee’s sharecroppers. “I am attempting a literary form in visual terms,” Gedney wrote in his notebooks.

IV.

The world of the now-defunct DoubleTake magazine, started by Dr. Robert Coles and photographer Alex Harris, was informed by the partnership of Agee and Evans, by the writers and photographers of the Works Progress Administration; these were its spirit animals. Other primary literary heroes were realists and authors of Southern fiction, Flannery O’Connor and Eudora Welty and Walker Percy and Joseph Mitchell, Studs Terkel and Raymond Carver, and William Eggleston and William Maxwell. Every issue ran the same poem by Seamus Heaney, which includes the lyric, “Call it miracle self-healing: The utter, self-revealing Double-take of feeling.” Published quarterly from 1995 to 1999 in conjunction with the Center for Documentary Studies and then less frequently for another five years afterward, it was conceived as “a home where image and word have equal weight, where photographers and writers have equal license to wander and to wonder.”

Even though it drew on a classic lineage, DoubleTake was a revelation, with its emphasis on portraying ordinary people—Gedney’s Kentucky photographs, photographs of factory workers about to be laid off, South Chicago short stories by Stuart Dybek, long-form reported articles by Susan Faludi—with its distinctive design, printed on beautiful, expensive paper, another way of giving images equal treatment and weight. It won a National Magazine Award for general excellence. You had extraordinary-ordinary-seeming people too, moments like Bruce Springsteen, a major supporter of the magazine, telling Walker Percy’s nephew Will what he thinks of Flannery O’Connor: “There was something in those stories of hers that I felt captured a certain part of the American character that I was interested in writing about…. She got to the heart of some part of meanness that she never spelled out because if she spelled it out you wouldn’t be getting it. It was always at the core of every one of her stories—the way that she’d left that hole there, that hole that’s inside of everybody.”

In its lesser moments the magazine could be overly earnest, at its best it risked that earnestness and broke through to reveal something else. Those of us who worked on it (I was a very young member of its editorial staff for a time) were aware that we were part of something special, and also something ephemeral. It’s hard today to describe the impact of the publication: as my former editor joked recently to me on the phone, “You mean a magazine with literary fiction and long-form nonfiction about regular people, and photographic essays and poems and book reviews and…?” Put that way, DoubleTake doesn’t sound terribly radical, or ground-breaking, yet no one has been able to reproduce it in scope or in feeling. Other magazines have copied elements of DoubleTake; every few years, since its demise in the early 2000s, it seems there’s yet another well-intentioned person out there attempting to grab the reins and revive the magazine, yet these have been limp resuscitations. It’s a shame that no one has quite gotten it since, even in a world that today insists on storytelling, and on reinventing narrative. The confluence of circumstances that made DoubleTake possible will not likely recur, so better then to look at its archives, a brief but compelling meditation and record of the possibilities and relationships that exist between words and pictures.

Among those, though, who credit the lingering influence of DoubleTake is Alec Soth, who not long ago Instagrammed a throwback picture of himself reading from the copy of the Bruce Springsteen issue. In that same issue, the Boss tells Will Percy how he keeps multiple copies of The Americans, that seminal book of photographs by another primary hero of DoubleTake’s, Robert Frank: “I’ve always wished I could write songs the way he takes pictures.”

V.

Soth has worked alone—this is the work he’s best known for—and in collaboration: with images solely, and with photographs and text together. For Iris Garden, published in 2013 by his imprint Little Brown Mushroom, he merged texts by John Cage with photographs from William Gedney’s archive, including some of the composer on a mushroom hunt, superimposing a weird, shifting narrative (the text was printed on inserts that can be moved throughout the book, set to different photographs). The book is striking and strange; it works on its own terms, evocative and suggestive rather than directly literal; and it suggests a less studious way for words and pictures to work together, more along the lines of W.G. Sebald’s photo-strewn ruminative novels and hybrid essays.

With the writer Brad Zellar, Soth made books like House of Coates, reprinted last year by Coffee House Press; to accompany the deadpan narrative that both artists purport is written by a vagrant named Lester, Soth made snapshots as if Lester himself were pressing the button on whatever camera he’d managed to wrangle; blurry, bleak roadside sightings.

Several years ago, Soth asked Brad Zellar to accompany him on a road trip. Both had newspaper experience lurking in their backgrounds; here, they’d be reporters, essentially, giving themselves imaginary assignments, gathering stories, working on tight deadlines, conducting interviews, making photographs of the people and places they encountered. Soth printed up business cards with the name The Winter Garden Dispatch, which would eventually become the LBM Dispatch, a broadsheet published irregularly by Little Brown Mushroom.

The first state was Minnesota, home turf for both. They went on to travel to Michigan, Colorado, Texas, Georgia, Ohio, as well as more specific yet nebulously mythic-sounding regions, Upstate (New York), and Three Valleys (Silicon, San Joaquin, and Death). Zellar wanted to eventually produce a Dispatch on all fifty states, a notion Soth put a stop to pretty much right away. “I’m the pragmatic one in the relationship,” he says dryly. “I knew that wasn’t going to happen.” Soth, who primarily works in color, shot in black and white; Zellar’s accompanying text swung between historical fact, oblique quotes from Willa Cather or William Gibson, and briefly captured stories and moments from the lives of carpet sellers, self-ordained ministers, train-hoppers, yoga instructors, the last snow-globe repairman.

“The Dispatch reported the news the way a paper would if Sherwood Anderson were the owner, Raymond Carver the copy chief and Emily Dickinson the sports editor, a vision of 21st-century life deeply strange and strangely deep,” wrote The New York Times Magazine, which published a selection of the Georgia issue.

The stories amplified the photographs and vice versa, each feeding the curiosity inspired by the other. Stories that made you want to see more, photographs that made you want to know more, mysteries and plots elucidated.

Indeed the project was after the dark heart of Winesburg, Ohio, as much as it was modeled on small-town papers, Agee and Evans, or the WPA travel guides, among the source material they consulted before visiting a new place. Going in, Soth and Zellar would have assembled an itinerary rooted in the history, literature, music, and idiosyncratic attraction native to the region, a list much like the ones Soth would tape to his steering wheel when working solo on projects like Niagara, his 2006 photo book of aspiration and drowned romance that loitered the motels and bars on either side of the Falls. He set his sights by a smattering of quotes from Lolita and, as he details in the notes at the end of Niagara, an updated catalog of what the roadside might deliver: “high-school yearbooks, Polaroids, men in pajamas.”

For the Dispatch, the list was more like extant worlds within worlds, and social networks mostly of the old order but also of the new: remote island communities, roadhouses, the Optimist Club, labor camps, the headquarters of Facebook. It was an exploration of loneliness. “There’s stuff I’m drawn to because I’m drawn to it,” Soth says to me. “With this project with Brad, I made a real effort to photograph more broadly. But my people—I can’t help it. I’d walk into a room and it might be filled with people, but I’d immediately see that one guy, and Brad would just look at me and sort of sigh and say, ‘Go ahead, do your thing.’”

Zellar, meanwhile, was doing his thing, not far removed from Soth’s; the stories amplified the photographs and vice versa, each feeding the curiosity inspired by the other. Stories that made you want to see more, photographs that made you want to know more, mysteries and plots elucidated. And yet, Soth says, “There was a frustration for me in the backstory, in feeling like I had to carry the weight of all these stories.”

In motel rooms at night they would post a roundup of the day’s findings on Tumblr; then came the broadsheet, weeks later. Over the course of things, it became clear that editions of the Dispatch would yield other forms too—both photographer and writer had more material than the Dispatch could hold—and a desire for the story to continue, and to be retold. “It was evolving and morphing, it had these other strands,” says Soth. “By the time we did Colorado, I knew we needed to have a another life for the project, and I expressed that to Brad.”

At what point does a newspaper become a novel? There are plans to create at least one other book from the note-taking of the Dispatch installments, the images made smaller, presumably treated. A reader or a travel guide, the photographer calls it, and if the Dispatch editions are any indication, it would resemble something in between a modern-day WPA travel book, a road trip story, and a Charles Portis novel. Certain of the photographs will have a gallery life too: concurrent exhibitions of the Songbook images are happening around the country, starting this week.

“I have a weird relationship where I want it both ways and I think I can have it both ways,” says Soth. “It affected the shooting; I would hold things back, the way I do when I shoot another project.” As he began to pull photographs from the various installments of the Dispatch (as well as others made around that same time) and put together the book that would become Songbook, he had a different title in mind, one he won’t reveal. “It was a working title, super personal, a way of taking back the pictures for myself and making them mine again.”

VI.

In recent years, an early manuscript of Agee’s was discovered, with the unpoetic title of Cotton Tenants; at 30,000 words, it was still well over the limit for Fortune, but certainly closer to the length of a magazine essay. Published by Melville House, along with many of Evans’s photographs, though spare and slim in comparison to Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, it is a book that defies form in it own manner, the novella to the epic novel qualities of Praise. It predates what Soth and Zellar, and Soth alone, are getting at by reinterpreting their own work, remolding what was initially a kind of artistic reportage. In that sense, they belong to a trajectory beyond the simple collaboration of photographer and writer; in that sense they are practitioners of a tenuous, evolving form that blends facts and insists on fiction. In a world that seems suddenly recharged with a desire to rework narrative, from Snow Fall to Serial, what is exciting about what Soth and Zellar are doing is how well they are succeeding at it: not just generating new forms of telling a story, but adding to and transforming this particular story, again and again.

Pictures are luckier, they are looser than words. Words have to fight harder to arrange themselves, to express that which in a photograph might be the mingling of order and accident.

Before Niagara went to press, Soth included handwritten captions and addenda, which appear in the index of images at the end of the book. “I couldn’t help myself,” he says; the stories are there in the photographs, of pawn shops and love letters and cheap honeymoon motels, but these were anecdotes too good to simply let go. Like liner notes for a record album, they opened up the larger story of the book’s making, and they stood, also, as stories on their own.

Toward the end of Songbook, he does essentially the same thing. In the acknowledgments, thanking the writer of all the words he’s just deleted: “While Brad’s words aren’t in this book, his spirit is everywhere.” Pictures are luckier, they are looser than words. Words have to fight harder to arrange themselves, to express that which in a photograph might be the mingling of order and accident, that strange convergence otherwise known as grace.

Songbook is complete when you arrive at its final image, an outline of a tiny, barely perceptible human figure alone in the midst of what appears to be a tundra, but turns out to be Death Valley. On its facing page is printed the only non-musical text of the book, by that playwright of solitude and the absurd Eugene Ionesco. I won’t tell you in this essay what Ionesco says. It’s really all in the photographs.

Rebecca Bengal is completing a collection of short stories and a novel. A former editor at DoubleTake magazine, her writing about photography has appeared in the New York Times, The Paris Review Daily, New York, Vogue.com, The Washington Post Magazine, and elsewhere.

Songbook by Alec Soth has just been published by MACK. His photographs will be on view at Sean Kelly Gallery, New York, from January 30 through March 14; Fraenkel Gallery, San Francisco, from February 5 through April 4; and Weinstein Gallery, Minneapolis, from February 20 through April 4. Issues of the LBM Dispatch are available at littlebrownmushroom.com.

To contact Guernica or Rebecca Bengal, please write here.