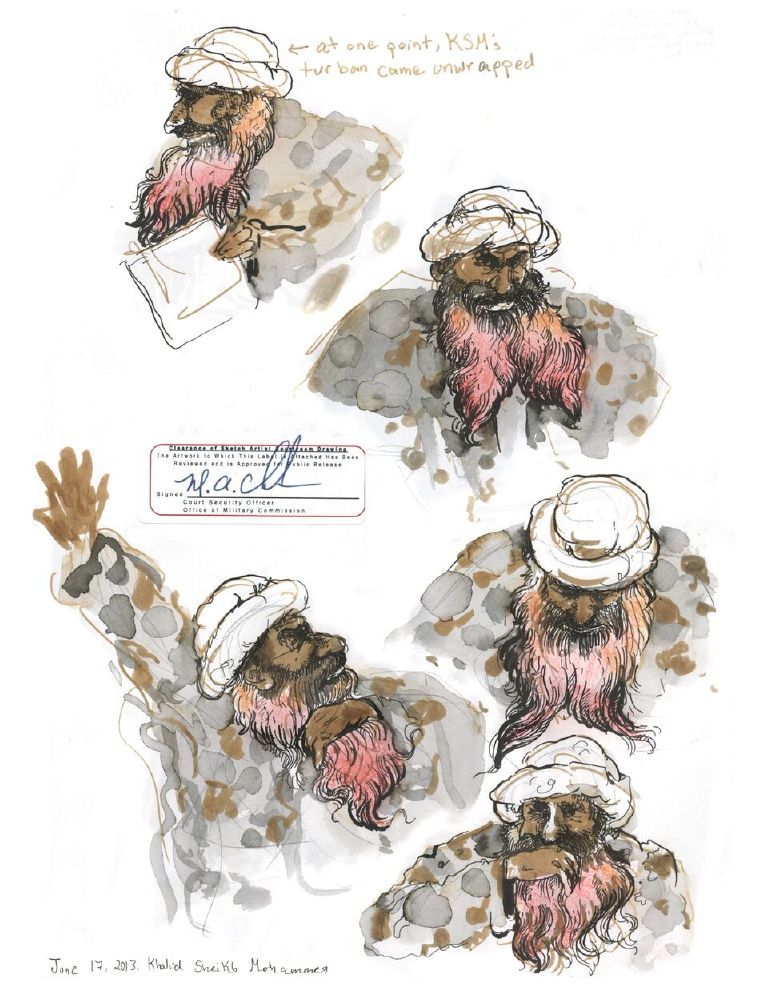

Walking the delicate line between fact and fiction, Lav Diaz’s films paint a bleak picture of his homeland, the Philippines. His movies are infamous for their lengthy run times, sometimes up to twelve hours, a device Diaz employs in order to depict conflicts in real time. He presents unflinching narratives of colonial oppression, including scenes of extrajudicial killings, abduction, and torture, both decades ago under martial law and in present-day Filipino society. Often, Diaz filters these themes through the lens of personal crises: Florentina Hubaldo, CTE (2012), for example, depicts the repeated rape of a young woman as a metaphor for four centuries of colonial oppression in the Philippines.

Diaz’s work has been shown at major film festivals, including Rotterdam, Venice, Locarno, and Cannes. Last year, the director won the Locarno International Film Festival’s chief prize, the Pardo d’Oro, for From What Is Before (2014), which explores the state of life in a small barrio before the declaration of martial law.

His 2013 Cannes entry, Norte, The End of History (2013), a Dostoevskian tale that takes place during President Ferdinand Marcos’s dictatorship in the 1970s and 1980s, is one of his only films released in the Philippines. Several of Diaz’s works were banned in his native country, including Melancholia (2008) and Death in the Land of Encantos (2007), despite gaining significant recognition at international film festivals. The director’s fan base continues to expand around the world, yet only a fraction of his own people have seen his work.

Diaz was born in 1958 on the Philippine island of Mindanao. He attributes his interest in film to two important figures: his father, who exposed him to international cinema at an early age; and Lino Brocka, the prolific Filipino filmmaker, whose movie Manila in the Claws of Light (1975) showed Diaz the possibilities of film as a political tool uniquely positioned to probe national traumas and social maladies.

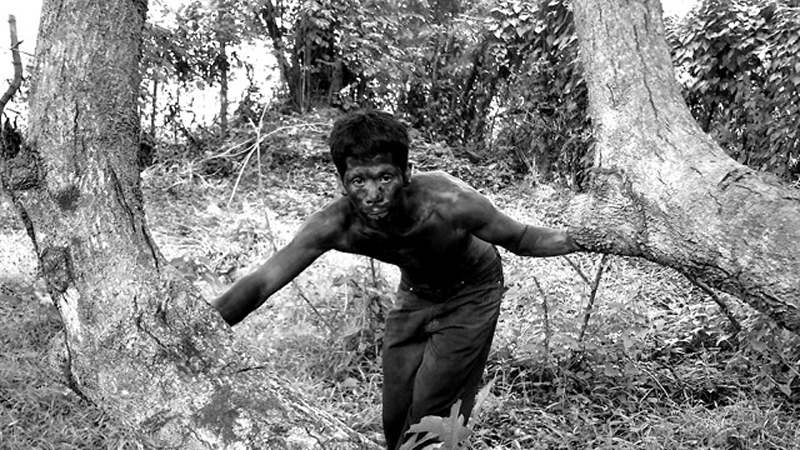

Among Philippine cinema auteurs, Diaz remains the only director whose persistent focus on traumatic national history is combined with an aesthetic informed by the country’s pre-Hispanic, Malay past. His characters almost exclusively inhabit the natural environment, often in underdeveloped but wondrous areas of the country that remain untouched by modernity.

I met with Diaz in Paris last month on the occasion of the two largest retrospectives of his work ever held in Europe, at the Jeu de Paume in Paris and the Cinémathèque Royale de Belgique in Brussels. We spoke about his upbringing, his singular approach to filmmaking, and how political events in the Philippines have shaped his vision as a director.

–Nadin Mai for Guernica

Guernica: Can you tell me about your parents, and where you grew up?

Lav Diaz: My mother is from the middle part of the [Philippines], from the Visayas. My father is from the north, the main island of the country, Luzon. He is Illocano, and my mother is Visayan. When they graduated from college, in the early ’50s, it coincided with the government’s program to open up this [region in Mindanao]. They called it “the pioneering days.” So when my parents graduated, they were invited to go there, and they went—they volunteered. There were no roads, nothing. They went to the villages and started building schools with the help of the government. There were many young volunteers, teachers especially. They started a school system.

We lived in Datu Paglas in the middle of the forest. There was no electricity; there was nothing. It was a very hard life. But looking back, it was good. I feel very grateful for what my parents did. I saw these issues—struggle, sacrifice, poverty. I understand my culture more because of that, and I’m very grateful to my parents for doing that to us.

Guernica: You dedicated your Pardo d’Oro award at last year’s Locarno Film Festival to your father. What role did he play in your becoming a filmmaker?

Lav Diaz: My father was a cinema addict. He would bring us every Saturday morning to a town called Tacurong. They showed double features. We were watching eight movies every week. We would go home Sunday night and have eight movies in our heads. Kung fu, spaghetti Western, Filipino melodrama, Japanese Westerns, everything. It was my film school.

Guernica: Your mother wasn’t into cinema at all?

Lav Diaz: Well, every time we went to the movies on Saturday morning, she would give us a lot of food so that we wouldn’t starve. When we came back to the house, we were covered in mosquito bites. The theaters were full of mosquitoes. She went crazy and got really angry with my father: “Look at the skin of our kids!” My father would just laugh it off: “They enjoyed the movies, so don’t worry about it.”

Guernica: What was the social and political situation in the Philippines at that time?

Lav Diaz: There is an extension to what happened during the war, when the Japanese rampaged us for four years. The Filipino guerrillas became the core movement: [during WWII] they were called Hukbalahap, the Philippine Army against the Japanese. The communist movement in the country started with the Hukbalahap right after the war. They were called Huks. Then we were under the American system. They gave us this so-called independence in 1946, but we were still part of the Commonwealth of America then. We were part of their imperialist movement.

Guernica: Did you witness any of those communist fights?

Lav Diaz: Not in our [region]. My father was a socialist, but he didn’t join the armed struggle. He was more into the cultural part—education, he focused on that. He didn’t want any violence, so he volunteered there to educate the indigenous people. It was actually very blissful in that area until the fight between Muslims, Christians, and the military in the late 1960s. Although there was this stark poverty and struggle, it was idyllic before then. Education was the center of everything. People were trying to help each other. Roads were being built in the area.

I was growing up in this barrio when martial law was declared.

Guernica: Mindanao has appeared in your films—for instance in From What Is Before. Do you have any specific memories of your life there?

Lav Diaz: Everything that you see there is from Mindanao. From What Is Before—you know, the shoot was hard. But the writing, the creation of the characters, the situations—it’s all from memory. It’s a composition of so many characters, from my parents, from my youth. I just put them together and created a narrative around them. It’s easy to create a narrative for me, because I really know the characters, the locale.

Guernica: You focus on the history of your country in your films, on the trauma of history: colonialism, oppression, dictatorship. I know that you also had your own traumatic experiences under martial law during the presidency of Ferdinand Marcos. In a way, martial law defined your teenage years.

Lav Diaz: Yes, I was one of the martial law babies; that’s what my generation is called. The martial law babies were divided into those who became loyal to Marcos, and the others, like me, who were trying to confront this very dark force in our history.

Everything [I experienced] is pretty much in From What Is Before. I was growing up in this barrio when martial law was declared. I was in my second year of high school. The Muslim-Christian war had already exploded, so we had to evacuate. My father brought us to a town near Manila to stay with some relatives as we couldn’t stay in Mindanao anymore. They burned our place. We were held hostage for a week, and they released us when the military negotiated with the Muslim rebels. We went to Manila and we stayed there.

Guernica: Did you go back to Mindanao at some point?

Lav Diaz: Yeah, we went back to Mindanao. We stayed in Manila for a year and then went back. My father bought a small piece of land, and we started over. My parents started teaching again.

Guernica: Were there any retaliations against your family members under martial law?

Lav Diaz: No, but relatives died, relatives went missing. My first cousin died. He joined the military and was shot by the communists. And one of my uncles, he mysteriously died. We think that he was killed by the military during the hamletting period. You were not allowed to go to your farm and check on it. He was so stubborn that he went to his farm anyway and was shot and killed.

Guernica: Because he was a communist?

Lav Diaz: Not even because you’re a communist. You were in a hamlet. If you got out, [soldiers] would shoot you, and they would declare you a communist. They would tell you, “If you leave this school, you know what’s going to happen.” Sometimes they would tell you, “Don’t leave your houses.” If they saw you in the fields, or in the mountains looking for food, they would kill you. There was a lot of that during the period, because of the Red Scare. They really feared the communists would take over Southeast Asia. It coincided with the mass killings in Indonesia also. While Suharto was doing this in Indonesia, Marcos was doing it in the Philippines, and Pinochet was doing it in Chile.

Guernica: It was all happening at the same time, in the ’60s and ’70s.

Lav Diaz: There were mad dictators. Their patron was the CIA. Marcos was being fed by the CIA, and by Nixon and Reagan. Filipinos were already going to the palace when an American helicopter rescued the Marcos family. If the Americans had not come, Marcos would have been killed there at the palace.

Guernica: You once mentioned that you had lost friends who were activists or who were opposed to the political situation in the Philippines.

I joined the movement in college, but then I went into music instead of joining them in the mountains. While they were dying, I was playing rock ’n’ roll and smoking marijuana.

Lav Diaz: Yeah, I lost a lot of friends. They joined the communist party, and they were killed. Especially in Mindanao.

Guernica: Have these losses influenced your films?

Lav Diaz: Yes, of course. It made me more committed to filmmaking, because I felt guilty that I wasn’t part of [their struggle]. I took a different path. I joined the movement in college, but then I went into music instead of joining them in the mountains. While they were dying, I was playing rock ’n’ roll and smoking marijuana. They died for a greater cause.

Guernica: Why did you choose to pursue music instead of joining your friends?

Lav Diaz: Well, I believed that I could be part of the cultural movement, because I wrote songs. I was trying to improve my music then. I think it’s part of my struggle as a cultural worker. I’m like my father—I’m not into the armed thing. I cannot be violent. My father was a hardcore socialist, but he couldn’t kill people. He didn’t join the Huk movement. Instead, he went into education to help the people.

For me, I’m interested in the cultural thing—music, then eventually cinema. It lessens my guilt.

Guernica: Do you ever feel that drawing from your personal trauma in your films is akin to a repetition of that trauma?

Lav Diaz: Well, my films are dialectical, so I kind of reenact the traumas to confront the past, to examine it. The narratives revolve around those things—the trauma of my people, the struggle of my people. You cannot escape it. These were big epochs in our history. You dig into the past. You examine the past. You create fictional characters, but at the same time, the narrative is affected by these historical things. It’s memory. It’s culture. It’s history.

Guernica: Is the endless repetition of the rape of Florentina in Florentina Hubaldo, CTE emblematic for your whole oeuvre, then?

Lav Diaz: Yeah, of course. The trauma, the torment—it’s a chronic thing. The constant torture—it’s about colonialism, imperialism, rape by the Japanese, and then eventually the Marcos period. This is CTE [chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a progressive degenerative brain disease]. It’s constant beatings from the 16th century down to the 21st century. It’s a chronic malady that keeps coming back. We need to confront it. The particular character I created is struggling to remember, and the constant beating is erasing all these things. These things want to defeat you, and Florentina Hubaldo is struggling to remember it.

Guernica: Do you think that you will ever be able to escape this loop in your filmmaking?

Lav Diaz: I don’t know [laughs]. Until I see that everything is okay, then I will not stop. It’s part of our responsibility as cultural workers in our lands. It’s easy to turn our backs and do other things—so-called avant-garde [films] or maybe pornography [laughs]. Even if I made pornography, the trauma would show, though. It will always be there because it’s my verité. It’s my kind of narrative, it’s my kind of storytelling. It’s not style; it’s just there. It’s my culture. I have to talk about it. I cannot escape it. It’s in the nature of my cinema.

I have faith in cinema. It’s my fucking church.

Guernica: You’re doing memory work for your country, and yet your films are hardly ever seen in the Philippines. What do you think a western audience can gain from your films?

Lav Diaz: They are aware now that there is a country called “the Philippines” [laughs]. They realize there is a struggle there. Latin America was struggling, the Philippines are struggling. We were rampaged by the Japanese and by Spain before that for almost 400 years. I’m not really disappointed that only Western audiences watch my films. That awareness creates a dynamic. You know, the films will come to our shores. It’s part of the struggle. I make films, and festivals, museums, and academia are embracing the work. It will be heard. It’s bound to happen because cinema is universal. You create it, some people will notice it, some people will watch it.

Guernica: Do you think you will see that day?

Lav Diaz: I’m not hoping to see that day but I know that my cinema will reach [Filipinos]. I know that they will embrace it one day. It will happen. I’m very sure of that. I still have faith in cinema. I still believe it can affect change. I have faith in cinema. It’s my fucking church. [laughs]

Guernica: Considering the subjects you tackle—extrajudicial killings, torture, abduction—does filmmaking represent a risk for you?

Lav Diaz: Yes, definitely. It’s always there, especially in places like the Philippines. It’s very dangerous.

Guernica: And you’re willing to take this risk?

Lav Diaz: Yes, of course. It’s a responsibility. Shooting these films, for example, is very treacherous. I fell into a ravine during the shoot of the latest film [working title Hele sa Hiwagang Hapis]. I’m still having this [pain] now. It has been four months, and I cannot sleep. You have to take the struggle of what’s going to happen during the [filmmaking] process as well as the consequences of it. It’s a commitment.

Guernica: But is your filmmaking also politically dangerous?

Lav Diaz: Yes, of course. With Norte, the End of History, the governor called me a persona non grata in Ilocos Norte.

Guernica: Thai filmmaker Apichatpong Weerasethakul said recently that he would leave Thailand for similar reasons.

Lav Diaz: Yes, it’s dangerous now in Thailand because of the military government. There is martial law there now.

Guernica: Exactly, and he no longer wants to make feature films in Thailand. He’s going to South America. Would you consider the same thing?

Lav Diaz: Well, in [your own] country, you can take care of yourself. At the same time, it’s open season. They can hit you at any time. I have friends who have been murdered, who have been shot mysteriously, who have been abducted. But I still feel safe, so I’m staying.

Guernica: Why do you still feel safe?

Lav Diaz: I’m very Malay. I’m very fatalistic about life. Whatever happens, happens. The imperative for me is that I do my contribution for my people, for my culture. I still want to make films for them. I still want to make films that confront our struggles.

My praxis is about being Malay—the struggle of the Malays before we became Filipinos.

My kids are [in America]. I can easily go there, or I can easily escape to some places in Europe with friends. But the place for me is the Philippines. The struggle is there. I cannot turn my back on it. It’s a responsibility.

Guernica: In Locarno last year, you said you were a Malay filmmaker rather than a Filipino filmmaker. What is the difference?

Lav Diaz: Maybe I’m just rhetorical about it [laughs]. “Filipino” is the Spanish side of our history. The islands were named after King Felipe, so we became known as Filipinos. It’s a brand, it’s a name. But we’re Malays. Before colonizers came to our shores, we were Malays. My praxis is about being Malay—the struggle of the Malays before we became Filipinos.

Guernica: If you’re a Malay filmmaker, can you be part of Philippine cinema?

Lav Diaz: Yes, yes, yes. There is a national cinema. At the same time, cinema is very universal. I don’t want to create borders as if Philippine cinema is so different from other cinemas. It’s just cinema for me. But you can call me a Malay filmmaker, or a Filipino filmmaker, depending on how you see those things—or maybe just a bum. [laughs]

Guernica: Your films are also very much inspired by Russian literature.

Lav Diaz: Yes, there are influences that come to the fore when you make these things. You cannot escape them. The novelistic attribute of my work is very much [like] the Russian way of creating novels. Tolstoy, Dostoyevsky—their work has so many gaps, so many spaces that if you were a so-called postmodern editor, you could cut War and Peace in half. But for the reader, you cannot erase those gaps because they are important. They contextualize the whole struggle. My cinema is like that. There are so many spaces, but you cannot cut them.

When I was trying to find my voice, when I was trying to create this so-called Lav Diaz verité, it just happened. At some point, I became very comfortable with the one frame, with the single take. It just happened. I didn’t plan it. I was looking for my own aesthetic, my own perspective, my own voice, and it happened.

I can see the influences of the Nouvelle Vague, the French New Wave. I can see the influence of Rossellini somewhere there. I can see the influence of Brocka. I can see everything now, looking back. I was trying to find my voice. I thought it was very original, but it’s not.

Cinema is the greatest mirror of humanity’s struggle. You see this alternative world, but…this is our world.

Guernica: I want to return to this idea of universal storytelling. Where does the universal begin? Is there a border in your films?

Lav Diaz: No, no. There is no border. I’m branding it as Malay cinema, but it’s just about cinema. Everything that I make is about humanity’s struggle, so there is no border, really. If you watch it, you see the Filipino landscape. That’s why you say it’s Philippine cinema—it’s made by a Filipino bum—but it’s really part of your own struggle, as a German, as a Brit, as a Latino, as a guy from the mountains in Canada, or as the aborigines of Papua New Guinea. There is no border. You can see yourself in these stories. This is the greatest thing about the power of cinema. It’s very present. It’s all there. You can’t escape it.

Cinema is the greatest mirror of humanity’s struggle. You see this alternative world, but you’re part of it. Everybody is part of it. This is our world.