Some years ago, the writer Siri Hustvedt interviewed Karl Ove Knausgaard, author of the autobiographical series My Struggle, before an audience. During the talk, she asked him why, in a book that referenced hundreds of writers, only one woman was mentioned. “No competition,” he replied. “His answer played in my head like a recurring melody,” Hustvedt writes. Despite the fact that Knausgaard’s book is emotional, vulnerable, and about the domestic realm—“feminine,” even—“competition, literary or otherwise, means pitting himself against other men. Women, however brilliant, simply don’t count.”

This is one of numerous illustrative, electrifying, and maddening stories told in Siri Hustvedt’s new collection of essays, A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women. In this packed volume, Hustvedt scrutinizes a delightful range of dilemmas—gender bias, perception, mental illness, memory, cognition—through an interdisciplinary lens. In one essay, she considers how gender inflects the experience of perceiving artworks. In another, she ruminates on the psychological, sexual, and social role of hair. Another, about her experience teaching writing to psychiatric inpatients, features moving close readings of her students’ poems and argues compellingly for “embodied psychiatry.” The central essay of the book, “The Delusions of Certainty,” is a sprawling two-hundred-page history of the mind-body problem and the myriad ways philosophers and scientists have sought to understand—and remain mystified by—the brain, consciousness, and the self.

What binds the essays in this collection together is an inclination to probe the boundaries between science and art—what the English physicist and novelist C.P. Snow called the “gulf of mutual incomprehension.” Hustvedt, while best known for her fiction, has a rigorous interest in the sciences and makes “regular excursions” to that side of the chasm, publishing papers in scientific journals, speaking before psychoanalysts and suicidologists, and lecturing in psychiatry at Cornell’s Weill Medical School. This book, she explains, is an “attempt to make some sense of those plural perspectives.”

Several of the shorter essays were published previously, and many are adaptations of lectures given to a range of audiences, from literature scholars to medical professionals. As a result, they’re designed for different levels of expertise. Some, particularly toward the end of the book, assume specialized knowledge the reader may not have, though patience yields vital insights. Because the essays were written discreetly, there’s a fair amount of repetition throughout the collection, but the accretion allows the reader to grow proficient with complex ideas. Philosophers—notably the seventeeth-century feminist Margaret Cavendish and French phenomenologist Maurice Merleau-Ponty—recur like old friends.

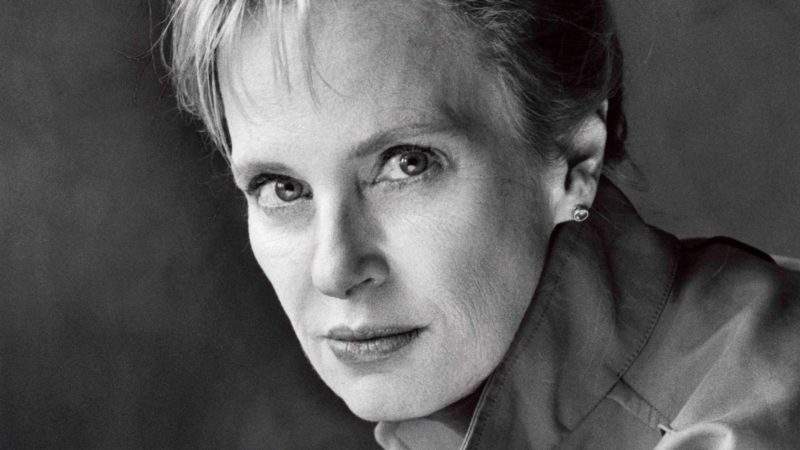

For admirers of Hustvedt’s novels (The Blazing World, about a brilliant female artist enraged by lack of recognition; What I Loved, a psychological thriller about art and identity; The Summer Without Men, a dark comedy about marriage; among several others), A Woman Looking at Men Looking at Women reveals the intellectual milieu from which her storylines and characters emerge; I repeatedly had the sensation that I was walking around in the library of her mind. On a recent rainy afternoon at her home in Park Slope, Brooklyn, we spoke about the value of learning new disciplines, the relationship between neurology and fiction, and the “liberating quality” of rage.

—Meara Sharma for Guernica

Guernica: Let’s talk about the gulf this new book confronts between literature and art and science. Why are you interested in traversing this gulf? What do these worlds have to learn from each other?

Siri Hustvedt: This is personal. I got really interested in science as a grown-up, though I have to say, when I was writing my dissertation at Columbia on Charles Dickens, that was when I became deeply interested in aphasia [loss of the ability to speak and understand language]. I was writing about how Dickens uses pronouns as keys to identity, and I found out an interesting fact about certain aphasia patients, which is that pronouns go fast. Also, personal pronouns are the last things that kids learn. A kid will call himself Fred. Fred wants a cookie. Because it’s much easier than understanding that an “I” moves from person to person.

I later realized, just thinking about what human beings are, that I was not very sophisticated about biology. And it corresponded with the explosion of work in neurobiology and neuroscience. So then I just threw myself into it and it was a big adventure, because first of all, you have to understand that there are different epistemologies. Like, how do I know what I know? It’s different, writing a novel and doing neuroscience. But after all these years of having immersed myself in science, I do think that if you master several different ways of thinking, it makes your own thought processes more agile.

I just did neurology rounds at Harvard and at Mass General Hospital. I visited a research group doing work on Alzheimer’s and dementia. There was a young woman there who did brain autopsy research on dementia patients after they’re dead. She explained, you know, slicing little pieces of the brain.

At the end, I said to them, “The reason I think that it’s important for people like you to read philosophy and literature is not because I think everyone should be a well-rounded human being, but because it will help you think better about what you are doing.” I feel that in the other direction as well, that having knowledge of the sciences if you’re a literature or art person, understanding what models are, how do you tinker with them to make them better, is something that is important to think about because in some sense that’s what we’re doing all the time.

In various disciplines people spend a lot of time digging tunnels that go straight ahead without looking side to side. And if they had looked side to side they would have seen an obvious error.

Guernica: Right. For example, in the central essay of the book, “The Delusions of Certainty,” you discuss how a dominant model for understanding how the brain works, Computational Theory of Mind—the brain as computer, separate from the body and the environment—can seem kind of absurd to someone who’s not a neuroscientist.

Siri Hustvedt: Actually treating the mind as if it were this problem-solving computational device—this seems so weird, right? It seems weird to the ordinary person, but it still continues to haunt neuroscience very deeply.

But what happens is, once you put yourself into the tunnel and you move step by step, then what is on one level preposterous ceases to be preposterous. Anyone who had access to introspection at all would say, “I have all these feelings, and feelings aren’t thoughts.” Trying to turn emotions into “cognitive acts” is like making a model, discovering a problem, and trying to squish that into your model.

Guernica: In that essay, you ask several people the same question: What is the mind? I wanted to know how you would answer that question.

Siri Hustvedt: I think that internal experience is brain generated. But you cannot isolate it to the brain. Our brain and our whole nervous system and our whole body are only created in relation to other people and to the environment. So what we have here is an enormously complex notion of both consciousness and unconsciousness. That’s why these models get very difficult, because you can’t reduce our subjective and intersubjective experience to neural reductions.

Look at language. It affects perception. In one essay, I talk about the spatial agency bias [the idea that our behavior and self-conception favor a certain spatial orientation—for example, in Western cultures, time is thought to unfold from left to right. Human interactions tend to be imagined in such a way that the agent of change appears on the left side, and the recipient appears on the right]. It’s so obviously related to our writing habits, because illiterate children and Arabic speakers, for example, have the reverse bias. So of course literacy affects our perception of the world.

I remember I did an interview in Paris with a wonderful young woman who was born in Vietnam but lives in France and is bilingual. And she said that in French, she’s liberated from familial hierarchies that exist in the Vietnamese language itself. When you’re talking to an older sister or your parents or younger sister the hierarchies are actually inside the pronouns. The relation that she has with those same people is in some way different in Vietnamese and in French.

So the idea that you can study a brain apart from others, as a static brain, is absurd. fMRI studies, as wonderful as the technology can be, are static images of a dynamic organ. They collapse time. You have no idea what was happening five minutes before, and there’s no developmental trajectory. Often these problems are ignored in the scientific literature.

Guernica: You’ve published papers in scientific journals. How have members of the scientific community received you, primarily a novelist, in their realm?

Siri Hustvedt: It could be that the scientists I know and scientists who invite me places to talk are people who are open to what I have to say. There could be innumerable others out there who have absolutely no interest or maybe even tolerance for my kinds of questions. But I have found that once I’m somewhere, say at a science conference, and I get into conversation with someone and they understand how much I know about what they know, people have been extremely open and interested in having conversations and even wanting to do that very science thing which is publishing a paper together.

This is funny but I’ve often found scientists more open than some people in literature. More generous in a way, more accepting. But I also think part of it is because, and I say this in the essay “No Competition,” it is true that you cannot define the worth of a novel. Novels become famous and last because a consensus grows around them that this is a valuable piece of work. And as we know there are also great things that are thrown away and may be revived later.

In science there are bodies of knowledge. You’re sharing that body of knowledge, yakking away about it, and trying to ask interesting questions. But there is something that can be mastered. There’s more of a there there, as Gertrude Stein said. Reviewing a work of art, though, you hardly know what it means. There’s no final standard.

Guernica: There are a couple of scientists and philosophers working on the mind-body problem who were disregarded, as you note, because their thinking got too close to God. And yet so many of the elusive and mysterious qualities of the mind—what is perception? consciousness? how does a thought form?—feel quite spiritual to me. I’m curious about your own relationship to the spiritual.

Siri Hustvedt: You know, this is a really fascinating question for me. There was a moment when I was writing “The Delusions of Certainty,” and I looked at the various thinkers I’m drawn to. William James. Michael Polyani, who writes about “tacit knowledge.” Alfred North Whitehead. Suzanne Langer. Simone Weil.

A lot of these thinkers, it turns out—with the possible exception of Langer—were mystics. They had a spiritual or religious dimension to their thinking. I do think that there is a transcendent aspect of human experience. I suspect that transcendent quality may be linked to a kind of intersubjective or collective human reality. I mean, that there is something more than this, the autonomous enlightenment subject.

Also I think it’s important to admit how much we don’t know. There’s a scientist at Columbia, Stuart Firestein, who wrote a book about the value of ignorance. And then in the New York Times I saw that someone is doing “ignorance studies.” That’s very interesting, because even being able to outline what is unknown is a helpful thing. There’s a lot we don’t know.

But I remember reading this long narrative account about a man who tried to do research on the feeling that you have when you know someone’s looking at you and you turn around. Most people have had this experience. But this researcher was essentially drummed out of science because it sounded too voodoo-like. To me it seems a perfectly legitimate thing to study. But no, this would not hold.

There are many things that are so weird that nobody studies them. Nobody wants to go there. In fact, hysteria—conversion disorder—was abandoned for a long time because nobody knew what it was. It was too weird. There are thousands and thousands and thousands of conversion patients. I mean, they can overwhelm neurologists’ offices. So they never went away, those patients. It was only with brain scans [that] you could see that a person with conversion disorder’s fMRI is different from someone who’s faking it. Like, you tell someone, “Pretend you can’t move your arm,” and then you have a conversion patient who has a paralyzed arm. The two scans are not the same. This began to dignify hysteria in the minds of scientists so they could suddenly work on it again.

Guernica: You write about how your ideas for characters and stories emerge from this unconscious realm that has been nurtured and fueled by everything you read, everything you experience. For example, in an essay about Louise Bourgeois, you talk about “ingesting” her, and then coming up with the character of Harriet Burden, the protagonist of The Blazing World, an artist who spends her whole life less recognized than she should be.

Siri Hustvedt: I knew I wanted Louise Bourgeois to be mentioned in The Blazing World, that she was someone important to Harriet Burden. But I didn’t understand how my immersion in Louise Bourgeois had probably been very important to developing the character of Harry. It was unconscious.

In an essay called “Three Emotional Stories,” I talk about the fact that I think at a kind of ur-level in the mind-brain, doing physics, doing philosophy, writing a novel—they are all the same. It’s all about this very rhythmic, muscular experience. I love this quote from Einstein. Jacques Hadamard, the mathematician, asked Einstein how he worked, and Einstein said, “None of my work has anything to do with science, either mathematical or linguistic.” He essentially said, “My work is visual, muscular, and emotional.”

When I read this I was so blown away because he was able to get hold of what most artists—and people working in many different fields—don’t really get hold of. You know, the question of, “How does it appear?” In my book The Shaking Woman or a History of My Nerves [a memoir about my neurological ailments] I talked about a friend of mine working in neuroscience. He was laboring over a formula with X and Y. I do not understand exactly what he was working on, but he was having terrible trouble with it for weeks. He went to sleep one night and had a dream about two brothers, X and Y, in combat. They were fighting each other. And the next morning he woke up and he had it.

There are many stories like this. There’s that mysterious aspect of our creativity, which I think goes across disciplines. It’s not limited to the arts but it certainly happens in the arts a lot.

Guernica: In the early stages of a creative project, how do you know what to capture from this unconscious space, what to bring down and turn into something? How do you choose?

Siri Hustvedt: It chooses you. You don’t choose it. That’s the strange thing about unconscious generation.

People work in different ways. I’ve heard about writers who make these huge maps, they have everything all worked out. And it seems as if they are just looking at it all from afar and all the choices are highly conscious. But the way I work, and I know the way many other writers work, is that the work kind of chooses you. And then when it’s going well, it… writes itself. And the very strange thing about the unconscious at work is that it knows more than you do. The book is actually in some funny way smarter than you are. The book is taking you into unknown places and you do not have the experience of choosing those places.

Guernica: Is there a point at which you have to switch? From it choosing you to you more consciously taking the reins?

Siri Hustvedt: Yes, I think when you’re editing sentences, for example. That is really often a work of aesthetics. Or shaping the plot. For example, many times when I’m working on a book I’ll go back to the beginning and read, because I want to feel the rhythm of the book—if it’s propulsive in the way that I want it to be propulsive, or if it takes a rest and then quickens again. No one wants to read a book that’s just a nursery rhyme for three hundred pages. You’ll die. So you have to have these different movements. So I’ll do a lot of that. And that’s quite conscious, but you’re also feeling it on some kind of gut level.

Guernica: I know you’ve been frustrated by having the autobiography label applied to your novels. How would you make a distinction between autobiography and drawing from this well of the unconscious?

Siri Hustvedt: Everything is autobiography and nothing is. When you write a book, what you’re looking for is emotional truth. And it has to be yours—because you look at a sentence or a story and it has to resonate as something true. But of course it’s not literally true.

My first book, The Blindfold, I would say is definitely autobiographical in the sense that I’m playing with my own autobiography. Iris [the main character] is my name backwards. She’s a graduate student at Columbia, like I have been, but nothing that happens in the book happened to me except that I too was in the hospital with migraine. Otherwise, I just invented everybody, but it feels very deeply true to me. It’s emotionally a very truthful book. The same with all my other books. Because I’m the writer of the book, I’m obviously mining my own emotional, psychic, and historical terrain. But there’s very little that’s taken directly from my life.

A writer I like very much, Colm Toibin, has been very clear about the fact that some of his works are out of his own life. But this is only celebrated. Why? Is it because I’m a woman that somehow autobiography is a criticism? Why is it that men who do much more of that are never criticized? In fact, it’s celebrated as sensitive and wonderful. I find that rather curious.

I think it’s a problem that is mostly unconscious, that women really are not supposed to be imaginative. That creativity of this kind is supposed to belong to men. You know, because women make babies. I find the double standards shocking.

Guernica: You write about the great gender disparity between male and female writers, but you also point out that literature, as with art, is often seen as feminine: “soft, emotional, unreal, frivolous.” If literature has all these feminine qualities, then why aren’t women just dominating the field of literature?

Siri Hustvedt: Well, because the masculine is always better. So a male writer dignifies the iffy femininity of art itself. That’s why I think in some ways, a woman working in science—and, believe me, women can have problems in the sciences, I’m not saying that it is all wonderful—is masculinized by her work and that lifts you a little up the hierarchy.

And a man in literature masculinizes writing. He gets that masculine enhancement effect.

Guernica: When did you awaken to a sense of what it means to be a woman in the world, in a political and social way?

Siri Hustvedt: I became a feminist at fourteen. That was really when the women’s liberation movement was in full swing. We’re talking about ’69, ’70. I had this copy of Sisterhood Is Powerful, a collection of essays from the women’s movement. And that thing, I read it within an inch of its life.

I also at that time read Simone de Beauvoir’s The Second Sex. I read The Female Eunuch. These were all kinds of classic texts from that moment. This is always my response to something. I read [laughs]. So I was no different at fourteen from the way I am now.

I remained a feminist but I think in my later years this has become more and more important to me. And it may be that as a younger woman, when I was the object of sexism, I wasn’t always sure and I would often blame myself: “Oh, I didn’t handle that correctly.” “There’s something wrong with me,” or, “I’m not good enough.” And as I got older, I began to realize, oh, this has absolutely nothing to do with me. I am utterly blameless here, and I’m being seen through this perceptual lens of either sexism or misogyny. You get older, you get more experienced, and you become more confident in yourself and you can make distinctions that were more difficult to make earlier.

Guernica: You cite this David Mamet quote that I found just searing: “Women have in men’s minds such a low place on the social ladder of this country that it’s useless to define yourself in terms of a woman.”

Siri Hustvedt: It’s a very raw statement, isn’t it? I think that it’s true, or mostly true. The operations of the culture industry, if you will, are exactly that. Why is it that so many men do not read novels by women? It’s because they’re tainted. It’s because you’re emasculating yourself by putting your self in the hands of this feminine consciousness. What gives you value is the way other men look at you. And women are just out of that. And not only that but you want to avoid being tainted by the feminine—the feminine is some kind of yucky thing that might, you know, pollute you. It’s more damning than making a hierarchy in which women are at the bottom. You’re not even in the hierarchy. You’re not even there.

If you’re a woman with, say, a doctorate, people often won’t use the title. But for all men they will. I’ve noticed this in Germany a lot. Same degrees, same education. And I remember when I was first doing research on Emily Dickinson in graduate school, almost all of the scholars addressed her as Emily. This is what John Richardson does throughout a three-volume Picasso biography. All the women are by their first names and the men are by their last names. It’s shocking.

Powerful women are terrifying. They terrify both men and women. I think because mothers usually are the people who take care of us when we’re little, and when we’re little those mothers are omnipotent, perhaps men even more than women don’t like to think about that dependency. That dependency is horror. Just thinking about you nursing at the breast of your mother is awful. And it’s worse for Republicans because they turned it into a creed. “The Nanny State.” What does this mean? Ben Carson said a couple of times that what he’s against is dependency. You don’t want to help these people out with their housing because it is going to make them dependent. The demonization of dependency is the demonization of the mother. It’s the same thing.

Guernica: Having been a feminist since you were young, are you angry about where we are now?

Siri Hustvedt: I take the long view. The long view is that in the United States and in many countries in the world, women have not had the vote for one hundred years. That’s one long lifetime. So that there should be ongoing prejudice and denigration of women is not surprising.

At the same time, I don’t really believe that progress is inevitable. Look what just happened in our country. This is definitely going backward. But I think taking a long view is good for one’s sanity.

And anger can be good. One of the wonderful happy parts of writing as the character Harriet Burden in The Blazing World was that she was so angry. It was so invigorating, I could just let loose with this character because that’s who she is. She’s just in rage. And it’s a kind of rage that has no depression in it. It’s just very focused. I thought of her anger as a kind of blade. I enjoyed it enormously.

Sometimes rage is a liberating quality. Rage is connected to the hope that things will be different. I think depression is really the opposite, depression is when you think there’s nothing to be done. Fortunately I always think there’s something to be done.

Guernica: Do you think that your desire to become an expert in science had anything to do with wanting to conquer a stereotypically male realm?

Siri Hustvedt: This brings up a subject that I am fascinated by, which is the idea of mastery. In The Shaking Woman, I say explicitly that having these unexplained seizures or shaking fits put me into this mode of thinking: Well, if you can’t cure yourself, you can know a lot about what there is to know about this thing. Writing the book was a way of mastering what was unmastered, in terms of my symptoms. But I think this applies more generally.

Demonstration of mastery gives a feeling of power and that feeling of power is a good feeling. It is a kind of pursuit of power. I mean I am deeply curious. I don’t think that my energy would be as high if I wasn’t so damned curious. But no there’s no question that I have a will to master material.

I remember some years ago I was having a very lively talk with a scientist, a woman, and we were talking about neuroscience and then I said, “You know, I just don’t know if I could ever really do molecular biology. It seems really hard.” She goes, “Oh, no, Siri, of course you can. Of course you can.” After that I thought, well, I’ll look a little more closely at these papers. You start out and you go, “What the hell is going on here?” But then you back up, you get some much more introductory text, and then you keep moving forward. And then after a while what was completely opaque became clear. Every human being who’s literate and curious and willing to do the work can do this.

Guernica: How much do you think your particular neurological disposition has to do with you becoming a writer?

Siri Hustvedt: I do think that because of my slightly pathological nervous system, I did feel like an outsider. This is something that many writers have. There are lots of writers who had a period of sickness. They usually did a lot of reading [laughs]. Feeling outside, feeling that my responses were not really like the other childrens’, that sense of an alien relation to other kids. I think that does prompt writing.

Guernica: I was intrigued by your explanation of your own mirror touch synesthesia, in which simply viewing others experiencing a sensation—whether pleasurable or painful—can produce that feeling in you. If in real life you experience intense identification with the feelings of others, how does that inform how you relate to your fictional characters?

Siri Hustvedt: I think there are two sides to that. On the one hand, the act of writing does take you out of that kind of stimulation because while writing, you are retreating from the world. So that’s a kind of nice safe place, your study.

But also I do think that it may have enhanced my sense of being the other, a kind of heightening of sensation, looking and then feeling. It has a binding quality.

I do also make the point about multiple personality disorder. What is it that prevents writers from real disintegration? When one is living with a character for a long time, someone who is different from you, are there physiological changes that go along with that? I think that would be very interesting to find out. The question has probably never been asked. It’s too crazy for the sciences. But I do think that’s an interesting question and I have a feeling that the answer might be yes.