History moves at a great speed. So great, that Nigerians might seem amnesiac. But images are less forgetful. A dictator is photographed a few decades before he becomes a democrat, a transition presented in a new, current portrait. The physical change in President-elect Muhammadu Buhari—between the 1980s and now—is evident. But we cannot know, simply by looking, if any true shift in mindset has occurred. These two photographs superficially hint at Nigeria’s history.

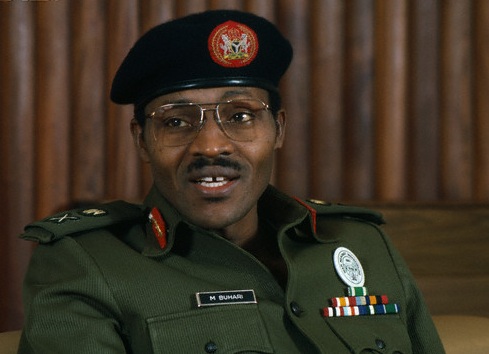

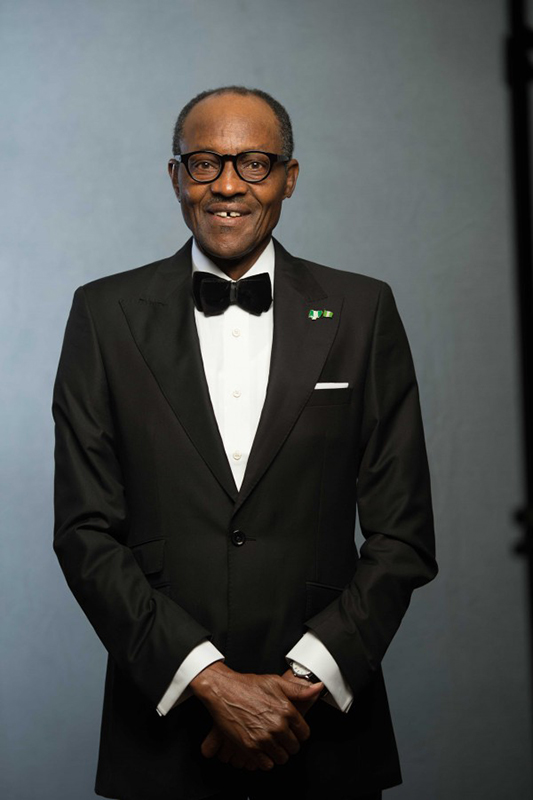

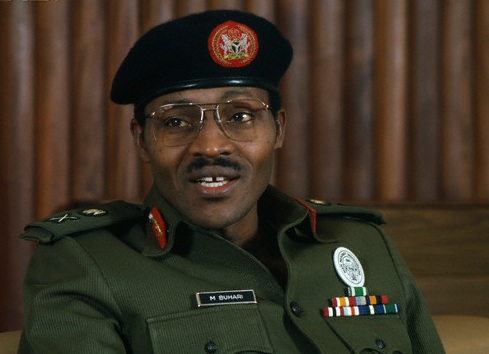

In the older photograph, possibly taken in mid-sentence by a member of the press, sometime between January 1984 and August 1985, Buhari is wearing a military uniform. His mouth is open, and even though wide-rimmed glasses cover his averted eyes, you can estimate the nature of his glance: unflinching and deterministic. In a more recent, official portrait, taken in 2014 by Kelechi Amadi-Obi, he is smiling, wearing a suit, a bow tie, with his fingers firmly interlocked. The rims of his glasses have sharper edges. His eyes are less energetic, worn with age. There are certain similarities between both images: he is sitting; his cheeks are raised in the same manner. In the older photograph, a name tag is pinned to his right chest, and in the recent one, a simple brooch in the form of Nigeria’s map, colored like its flag.

When the first was taken, Buhari was military head of state. He had come to power by ousting a civilian government. He kept a stern pose during that period. His expression in military-era photographs is direct and authoritative. By the time the second picture was taken, he was a presidential aspirant in a fledgling democracy. He was, in one way, looking at an electorate that on three earlier occasions had found him unfit for civil rule. In 2003, 2007, and 2011 he ran for office and lost. He now smiles, looking directly at the camera, seeking mass appeal. This change, in one sense, is related to rhetoric. “Change” was the slogan of Buhari’s All Progressives Congress (APC). The reelection bid of the outgoing president was tagged “transformation” by the People’s Democratic Party (PDP). Both words, like duplicates, refer back to each other. It becomes clear what sort of division exists between the PDP and the APC: one without any specific ideology. This is merely a power scramble, camouflaged.

The choice of photographer for the more recent photo is instructive. Kelechi Amadi-Obi might have been chosen for his prominence and clientele, which includes public figures and multinationals. A video interview, uploaded to Jimi Agbaje’s official YouTube Channel, however, suggests another reason: the photographer’s mastery in creating public photographs, his ability to orchestrate public personas. During the campaign photo shoot for Agbaje—PDP’s gubernatorial candidate for Lagos State—Amadi-Obi said: “Today we’re going to do PR photos…. It’s to tell the story of confidence…somebody that is a visionary. How do you extract personality? That is the assignment here.” In accepting to work with opposing political parties, is a photographer necessarily unaffiliated and unbiased? Perhaps this was the case, generally, for Amadi-Obi. But in Agbaje and Buhari’s shoot, the photographs he took weren’t politically neutral. Photographs are hardly ever impartial.

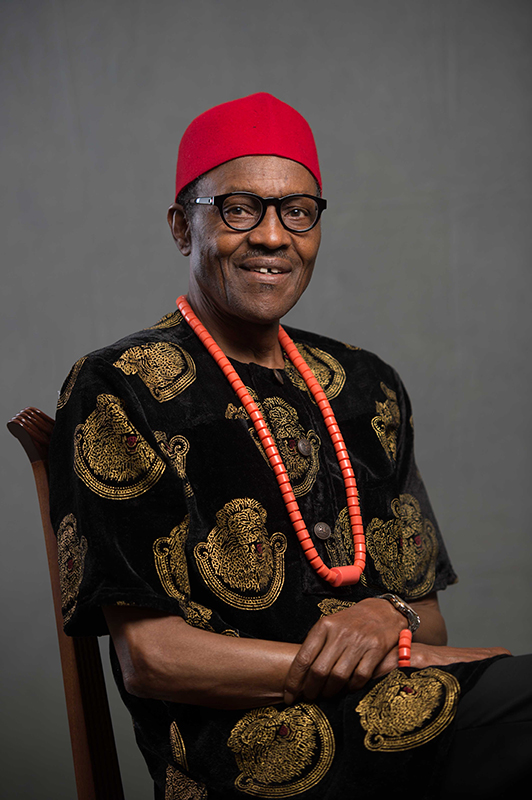

In both instances, three decades apart, Buhari’s photographs were intended for the public gaze. Because of its repeated use and circulation, it is hard to tell in what circumstances the first was released. The second, however, was released at the outset of Buhari’s presidential campaign, in the weeks leading to the party primaries. (The APC campaign was briefly advised by President Obama’s former campaign manager David Axelrod’s consulting firm.) A series of portraits was made public at that time in which the future president looks directly toward the camera at potential voters; he is dressed alternately, in the various choice attires of major Nigerian ethnic groups. A number of popular Nigerian fashion and lifestyle websites published the portraits as newsworthy posts. Some commenters were apathetic. “This man’s open teeth can neva deceive us he is just a walkover, he wont win…all this money he’s wasting he should use it and help the charities”; “If you like wear dansiki or suit or dress like angel mike it cannot hide the evil in your heart.”

Others commented favorably: “His credibility even speaks in pictures, he’s so cute in these variety of clothings, so why won’t I want to flaunt him as my President.” Someone else wrote: “Can anyone, even those who despise him deeply, deny that Buhari looks Presidential in the picture below?” Did his supporters, some adopting the new set of images as their avatars, recall the existence of the other photograph? Did they see any connection? More importantly: Did they accept Buhari’s validity as a civilian president by the fact that he wore civilian clothes? Pairing the photographs arguably heightens skepticism about Buhari’s intention, or potential. Does the second photograph rationally illustrate change? In a recent interview with Bloomberg TV Africa, Nigeria’s Nobel Laureate playwright and poet Wole Soyinka said, “Against my rational instincts, I believe that we have here a genuine case of a born-again democrat.” But earlier, in 2007, he had written: “The grounds on which General Buhari is being promoted as the alternative choice are not only shaky, but pitifully naïve. History matters. Records are not kept simply to assist the weakness of memory, but to operate as guides to the future. Of course, we know that human beings change. What the claims of personality change or transformation impose on us is a rigorous inspection of the evidence, not wishful speculation or behind-the-scenes assurances…. In Buhari, we have been offered no evidence of the sheerest prospect of change.”

Soyinka’s colleague, the late novelist Chinua Achebe, was steadfast in his rational invectives against the Nigerian political class. A fine example is his 1983 book, The Trouble with Nigeria, published a few months before Buhari led a coup against Shehu Shagari, then the civilian president. The core of Achebe’s argument was summarized at the outset, in the first sentence: “The trouble with Nigeria is simply and squarely a failure of leadership.” Achebe dedicated his book to his children and their contemporaries throughout Nigeria. However, thirty years later, it is the generation of Achebe’s grandchildren that constituted a large percentage of 2015’s voters. Their relationship with the book, and with the past in general, is mediated by decades of short-lived transformations and failed palliatives. Can the photographs prompt a similar sentiment? What do the photographs mediate?

The lapse of time between the two photographs is a kind of interregnum. Given his sins during the first go-around, it is difficult to estimate how a new Buhari will convince Nigerians, even the world, that he is a born-again democrat. But perhaps the interval allowed a resolute Buhari to morph into a man of the people. The second photograph emerged at a moment when the definition of political leadership in Nigeria was being questioned. The elections were pivotal. Young Nigerians, especially those buoyed by a non-hierarchical social media, made a case for an Office of the Citizen, the idea of which gained popularity due to the efforts of Enough is Enough Nigeria (EiE), a coalition of individuals and organizations committed to good governance and public accountability. Six weeks before the elections, Chude Jideonwo, a founding member of the coalition, wrote in New African Magazine: “You can ask a lot of young people why the historic momentum around the 4th-time-around candidacy of General Buhari has improved and many will tell you: ‘We are not voting for Buhari as much as we are voting out Jonathan. We do not know if Buhari will do better, but we know we cannot reward the last four years of Jonathan.’”

Up close, whether onscreen, in newspapers, or in campaign posters, portraits generally accommodate our impassioned scrutiny. If the portrait is of a prominent politician, displayed publicly, we can hold the politician accountable by being aware of his own orchestrated depictions—with the knowledge that photographs, at best, do not depict an entire truth. As a civilian considering Buhari, accountability takes the form of retroactive engagement with Nigeria’s democracy. And such accountability is a trans-historical, never-ending task.

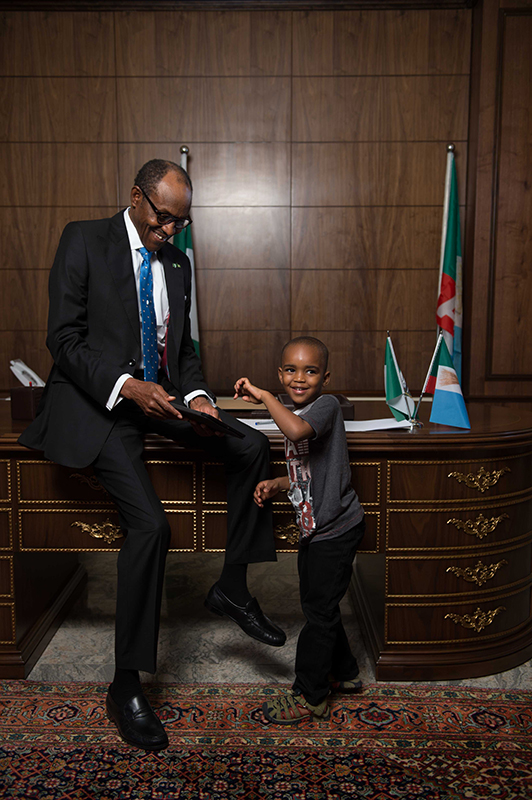

More images from Muhammadu Buhari's 2014 presidential campaign.

Emmanuel Iduma is the author of the novel Farad (Parresia Books), and co-editor of Gambit: Newer African Writing (The Mantle). He works as director of Saraba Magazine and director of publications for Invisible Borders Trans-African Organization.