The Negro was unsexed and made to eat a portion of his anatomy which had been cut away. Another portion was sent by parcel post to Governor Dorsey, whom the people of this section hate bitterly.

–lynching of “Negro” Williams, Moultrie, Ga., Washington Eagle, July 16, 1921

Four young women from the crowd pushed their way through the outer rim of the circle and emptied rifles into the negro. They stood by while other men cut off fingers, toes and other parts of the body and passed them around as souvenirs.

–lynching of Philip Gathers, Bulloch Gounty, Ga., Atlanta Journal, June 21, 1920

A crowd of twenty men battered the door of Cooper’s home and pounced upon him with knives and axes. He was killed as his wife looked on. The body was tied to a buggy and dragged to the church. Torches were applied to the house of worship, and when the flames were licking high into the air, Cooper’s nude form was thrown into the blaze.

–lynching of Eli Cooper, Eastman, Ga., Chicago Defender, Sept. 6, 1919

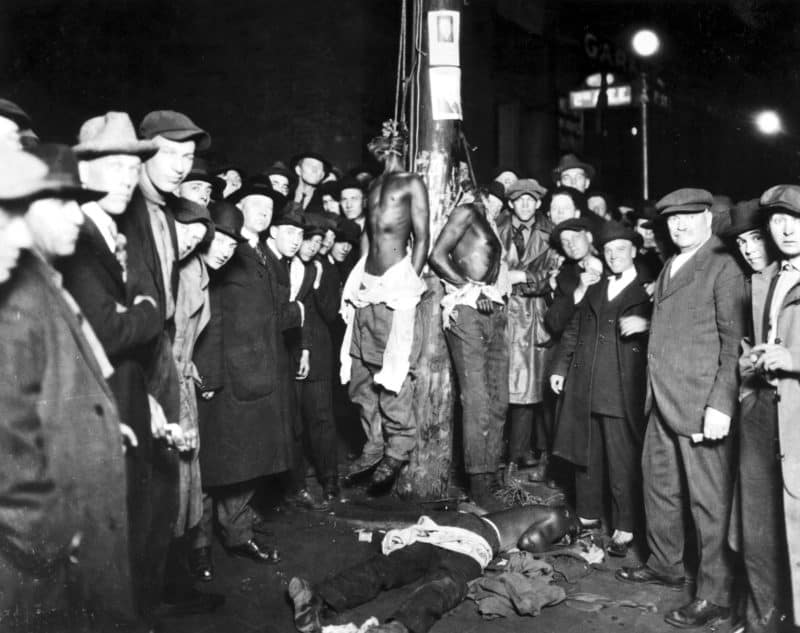

These shocking and gruesome accounts of lynching in 100 Years of Lynchings are just three of the more than 500 recorded lynchings in Georgia from the 1880s until the mid-20th century. Less than a half century after the last recorded lynching in the state, Clarence Thomas, a son of the Peach State, claimed on national television to be the victim of what he called a “high-tech lynching” after credible allegations emerged that he had engaged in sexual harassment of a female employee while he was head of the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission. Thomas, then a sitting federal appellate court judge, was in line to serve on the highest court in the most powerful country in the world.

With his white wife seated behind him, Thomas described his Supreme Court confirmation hearing as “a high-tech lynching for uppity blacks who in any way deign to think for themselves.” The words and imagery were shocking and powerful, and reset the course of his confirmation hearings.

Now the “high-tech lynching” claim has been invoked in a campaign ad on behalf of another son of Georgia, presidential candidate Herman Cain, in an attempt to fend off negative fallout from the revelation that Cain was accused of sexual harassment by several women in the 1990s during his time as president of the National Restaurant Association.

There is no record of a black man ever facing lynching for engaging in sexually inappropriate conduct with a black woman. As a Southerner, [Clarence] Thomas no doubt knew this.

Whatever one thinks of either Thomas or Cain, neither is the victim of a lynching, and their deliberate invocation of the most hideous and grotesque of racial crimes to shield their own conduct from scrutiny profoundly misrepresents the significance of lynching in the racial history of this country. In fact, it is an insult to the nearly 5,000 African-American men who were lynched (and a few dozen African-American women as well) from the 1880s until the 1960s to continue trotting out this imagery as a convenient way of cowing critics—white and black—into ignoring claims of sexual harassment.

The men who were lynched in nearly every state in this country suffered unimaginable terror and pain, and they suffered it alone. They were not millionaires, or former chairmen of Federal Reserve boards, like Cain. They had no public relations firms representing them, or well-funded political groups organized to plead their cases. Not even their families could help them. In fact, in the aftermath of a lynching, the families of victims were often so frightened they did not claim the remains of their loved ones, fearing that bloodthirsty lynch mob members would exact violence against the families as well.

Thomas should have known better than to invoke lynching imagery to describe the Senate Judiciary Committee’s decision to examine the claim that he had harassed Anita Hill. There is no record of a black man ever facing lynching for engaging in sexually inappropriate conduct with a black woman. As a Southerner, Thomas no doubt knew this.

In fact, even the old saw that lynching was primarily utilized to punish black men for raping white women was debunked in the early 20th century in a study carefully prepared by anti-lynching activist and newspaper publisher Ida B. Wells-Barnett. Her study showed that lynchings were most often exacted in response to allegations that a black man had assaulted or killed a white man. Later records bore that out.

The victims of lynching were not just the thousands of men who were tortured and stripped of their humanity, often before cheering crowds of housewives and children. Lynching was a community crime, designed to frighten entire black communities into submission. And it did.

When civil rights workers tried to register voters in Sunflower County, Mississippi, in the 1950s, they found black sharecroppers still telling the story of one of the most grotesque lynchings ever recorded. Luther Holbert and his wife had chunks of their flesh taken from their bodies with screws, and their fingers and toes cut off before they were finally burned to death. Although this lynching had happened decades earlier, in the 1950s it still held the small black sharecropping community in Sunflower County in the grip of paralyzing fear.

What does this history of lynching have to do with the fact that the National Restaurant Association decided to pay tens of thousands of dollars to women who accused Cain of sexual harassment in the 1990s, or that Thomas was alleged to have persistently made unwanted sexual remarks to a female subordinate while he headed up the federal government’s employment discrimination agency? In a word, nothing.

What Cain hopes to gain from describing himself as a lynching victim is precisely what Thomas received: the shame and fear of white liberals, who, in Thomas’ case, failed to adequately investigate and expose the credible testimony of witnesses who by all accounts would have corroborated Hill’s claims. Many have persuasively argued that had then-Senate Judiciary Committee Chairman Joe Biden (D-Del.) called other witnesses who were prepared to attest to Thomas’s misconduct, the result of the 1991 hearings and the confirmation vote would likely have been quite different.

Lynching victims were not metaphors. They were real people who suffered unimaginably.

And this is why it’s important that we talk about what lynching is and isn’t. The history of lynching in this country continues to hold enormous power in our imagination. Being accused of participating in a lynch mob is among the most incendiary charges one can make in this country.

What W.E.B. Du Bois called “America’s national crime” has been the subject of movies, songs, poems and plays. The very word invokes terror, shame and fear and is enough to make the media, Republican and Democratic opponents and perhaps even the alleged victims of Cain’s misconduct just want it all to go away. Using the term “high-tech” to modify the charge does little to alleviate the power of the accusation or to lessen its ability to silence critics.

The mere fact that you are a black man accused of sexual misconduct does not make you a lynching victim. Nor are you a lynching victim just because members of your own party think you are a poor choice to fill the newly empty U.S. Senate seat of the just-elected first black president, as Roland Burris was when State Sen. Bobby Rush (D-Ill.) begged the skeptical press not to “lynch” Burris in December 2008.

If you are a black millionaire, running to hold the most powerful office in the world, or a black federal judge seeking a seat on the highest court in the country, and you are questioned about sexually inappropriate conduct toward women in your employ, you are not a lynching victim. You are the privileged descendant of a generation of blacks who endured the terror of lynching—of hanging and burning and dismemberment—and who lived lives of fear and discouragement that are unimaginable to us.

Once and for all, besieged black Republicans—indeed, any public figure subjected to media scrutiny based on allegations of wrongdoing—should drop the manipulative and deeply insulting invocation of lynching, high-tech or otherwise, to try and disarm their detractors. Lynching victims were not metaphors. They were real people who suffered unimaginably. Using lynching as an expedient way to derail accusations of sexual harassment makes a mockery of those who died and the communities that lived in the grip of lynching’s terror.

This post originally appeared at BeaconBroadside.com.