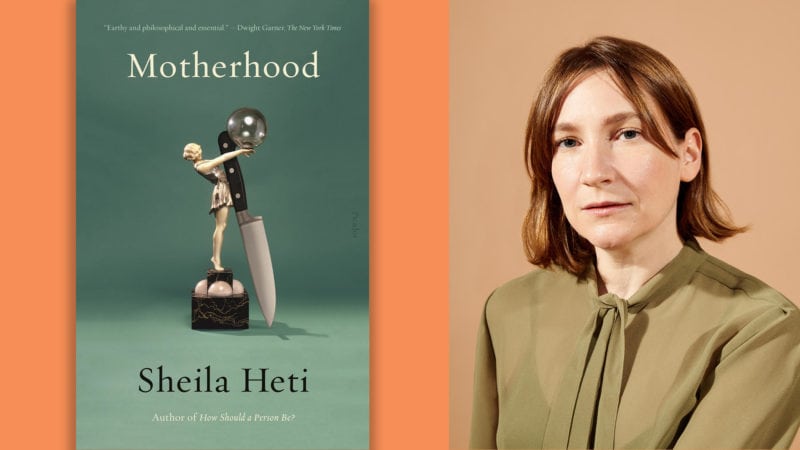

In Motherhood, Sheila Heti’s third novel, the unnamed narrator wrestles with the question of whether or not to have a child. She consults her friends, her partner, her dreams, tarot cards, a psychic, and the I Ching. Frustrated that the years of thinking and writing about this question haven’t produced a definitive answer, she instructs herself to “imagine the questions of someone else, someone with a broader mind—then try to be that broader mind.”

For many readers, Heti already is that broader mind. Her second novel, the acclaimed How Should a Person Be? took as its title a question that Heti tries to answer in much of her work, whether the overt subject matter is female friendship, art-making, motherhood, or clothes.

Because the material she uses to answer that question often comes from her life and the lives of those around her, she has been discussed alongside writers like Rachel Cusk and Karl Ove Knausgaard as exemplars of “autofiction” (a category Heti has said she finds superficial), and her concern with female friendship and how women relate to one other has drawn comparisons with Elena Ferrante’s Neapolitan quartet.

But I had not heard Heti speak much about her relationship to Judaism, biblical stories, or visual art, though all feel important to her work. Over email, we discussed these and more.

— Kelley Deane McKinney for Guernica

Guernica: Many of your books are organized around explicitly asking a central question, and you seem to try and answer these questions, to some extent, by talking to the people in your life.

I recently reread many of the interviews you conducted for The Believer and noticed that, as early as 2009, you were asking the women you interviewed about motherhood. Is there a question that you’re currently asking the people in your life?

Sheila Heti: No, I don’t think I am asking questions of anyone these days. There was a part of me that was very active for a number of years, which believed other people had answers I did not, or that if I heard other people’s answers, I would be able to find my way to my own. I put everyone above me. Everyone was an oracle, an authority. Something happened to me since then, to cause that conviction to disappear. I used to take a lot of pleasure in going out with someone and talking to them for hours, and the things they would say would remain with me for a long time, like reading a great book. But now when I talk to someone for hours, I go away and pretty soon I am back to having nothing. I miss feeling that same connection, but I also feel more free.

Guernica: Did something specific happen to cause that conviction to disappear?

Heti: I grew up. I’m talking about a change that happened gradually over more than ten years.

Guernica: There’s a moment in The Chairs Are Where the People Go, when Misha Glouberman tells you, “There’s an inclination to think that with enough research and thinking and conversation and information, it’s possible to determine what the correct decision is; to think that decision-making is an intellectual puzzle. But generally, it’s not. You make decisions.”

Your books often focus on people trying to make a decision in the present about their futures. In your writing, people don’t seem to suffer many regrets or do a lot of reflecting on past decisions. Why not?

Heti: I suppose because I don’t feel much regret, so it doesn’t occur to me to write about it. I don’t reflect a lot on past decisions, so I don’t write about people doing that. I have a very bad memory: I’m not sitting around thinking about ten years ago. I’m wondering about how to make something: my life, a book. How to make a friendship better. I’m wondering what the present is asking of me. I’m wondering if there is something the future needs that I must put into place in the present. I’m worrying about whether there is something I’m supposed to be doing, for the sake of the future, that I’m not. I worry that I’m not looking in the right places, or that I’m paying attention to the wrong things. All that is more real to me than regret.

Guernica: One book I love, and that reminds me of your work, is Nell Dunn’s Talking to Women. In 1964, she conducted a series of interviews with her female friends, where she asks them questions about their work as writers and artists, their children, their men, and whether or not they feel free.

One of the questions she asks reminded me of the tone of your writing. But then I realized I also just hoped you would answer it: “How can one achieve a balance between being so emotionally sensitive and in constant danger of nervous breakdown and alternatively being so tough life becomes meaningless?”

Heti: I wish I knew the answer. Maybe it’s too much of a commonplace of our time to think that “balance” is the answer to every question. Maybe the point is to be very emotionally sensitive, rather than to balance sensitivity with toughness. Maybe you should find the right thing to do with your sensitivity. Maybe that means making art in a moment of sensitivity, instead of yelling at your boyfriend. Or maybe it means crying or reading or being alone or helping someone. Maybe it’s not about balancing sensitivity with toughness, but about putting your sensitivity into a tube where it can come out a little more beautiful and interesting, rather than putting it into a tube which amplifies the pain, and hurts others and harms your life.

Also, I don’t think toughness equates with meaninglessness. Sometimes an overwhelming sensitivity can also tip into feelings of meaninglessness. Also, I don’t think meaninglessness is necessarily a bad thing or the wrong thing to feel about life.

Guernica: Your work isn’t often discussed as part of a Jewish literary tradition, but Judaism appears quite a bit in Motherhood and How Should a Person Be? In what sense do you think of yourself and your writing as Jewish?

Heti: Well, I am Jewish, and I grew up with Jewish stories. I lived the stories of Judaism through enacting the rituals of the religion with my family. The stories weren’t abstract. They were lived with my parents and my brother and my uncle and my grandmother. I loved the holidays, and how the food we ate, and the way we sat around the table, and lit the candles, was all connected to a religious story, and every gesture had meaning.

This merging of the symbolic with storytelling, in a lived life, is how I want to write my novels: I want the gestures I choose (or happen) to make in my actual life to be symbolically meaningful in relation to a story (a story I write), and I want my writing to act as a guide to future behavior. I consider my recent books both records of what I have wrestled with, and instructions for me on how to wrestle in the future, and (during the years of writing them) they were instructions about how I should be living in order to write the books. All this seems not so different from setting out certain symbolic foods every year at Passover, and eating them with others. To meld the deep human inclination to tell stories with the desire to live a decent life, ruled by a book—I think this is maybe how I understand myself to be a Jewish writer.

Also, there is the humor, and there is a neurotic quality to my books, which is typical of North American Jewish writing and comedy. The circling, the self-doubt, the self as a clown of failed intentions, the recognition of the failure of the intellect to solve anything… all that is also there.

Guernica: In Motherhood, you write: “I knew that God was not true,” but in both Motherhood and How Should a Person Be?, you use God to work through questions you are trying to answer. What makes the idea of God useful to your writing?

Heti: I think God, for me, represents the hope of some kind of order. When you’re writing a book, you are also hoping that there is some kind of fundamental order that you can find through writing it: as if every book is born with its own order in its cells, and it’s your work to find it and bring it out. I hope this of life, as well: that there really is some kind of order. I suppose one could leave out the word God and just say nature or science, if one is talking strictly about an order. But while nature and science mean order, they don’t also mean hope. God somehow represents both order and hope—I suppose the hope that the order has meaning; it’s not just a structure, but a structure for a reason, which, even if it’s withheld from us, still exists.

Writing a book is a sort of leap of faith: that you will eventually create an order that has meaning. To think about God is maybe to prime in oneself the feeling that what you are writing will have order and meaning, the way life perhaps does—and hopefully this inner feeling will lead to it being true in your work. Maybe God is even helping the book come into being, as a best case scenario.

Guernica: The stories of Jacob wrestling with the angel and Moses leading the Israelites out of Egypt appear in both of your recent novels. Do you feel close to biblical writing in general or are those two stories an exception? Do you get something out of biblical prose that you don’t get elsewhere?

Heti: Those stories came into my books quite naturally. I realized as I was writing these books that the stories had, in ways, been written before, in the Bible, so I folded those stories in to see how they might expand or change or shed light on what I was telling. I don’t think it has to do with the prose, I think it has to do with what is being told. But the simplicity of the prose, and their psychological depth, makes biblical stories very open to being used in other stories. Those stories are so deeply woven into Western culture, it really makes more sense to say that my books emanate from the Bible, than that biblical stories appear in my books.

Guernica: I was surprised to hear you say that you don’t get much from biblical prose, which you also describe as simplistic. To me, biblical prose is dense and compressed, at times layered with symbolism and at others factual and direct. This reminds me of your writing, which often feels like it would not be out of place in the Old Testament:

“I had always thought my friends and I were moving into the same land together, a childless land.”

“I felt an intelligence up close to me saying: I have made this person for you. Why are you rejecting him?”

“The one [life] you are given is the one to put a fence around. Life is not a harvest. Just because you have an apple doesn’t mean you have an orchard. You have an apple. Put a fence around it.”

Part of my confusion is that you say what matters is the stories that are told, but in some ways biblical stories seem impossible to separate from the language that tells them. The prose mirrors the stories that are being told: of dire consequences, the fate of the earth, the effort of living a decent life. If your books emanate from the Bible, is it possible that some of your prose emanates from there as well?

Heti: I didn’t say the prose was simplistic. I said it was simple. Maybe I should have said “clear”? I don’t know where my prose style comes from. Perhaps it does come from the Bible, but perhaps from my reading of myths and parables, or just literature in general. And also transcribing speech. At this point, it’s a sort of mirror of the way I think, and it’s the kind of music I like in prose. The apple bit is drawn from my reading of the Talmud; the idea of fences comes from there. I don’t know where the structure or mood of my sentences come from, besides the fact that I worked for them.

Guernica: The decision-making that you describe in your novels often has recourse to mystical or supernatural elements (tarot cards, the I Ching, palm readers). Why isn’t reason adequate to answer these questions or make certain decisions?

Heti: Maybe reason is adequate, but it’s not literary. Someone who is interested in reason writes essays or philosophy, not novels. Besides, I don’t think the questions I am asking can be answered by reason or logic (what is my relationship to time? how should I live?) but only through the annoying, circular thinking that happens alongside living; thinking that is more emotional and symbolic than rational. I’m interested in chance, fate, doom, luck, history, fear, desire, self-delusion, blind enthusiasm, episodes of futility and exhaustion—I think these are the things that decide who we love, what our values are; these are some of the inner forces that make our most intimate decisions—not logic or reason.

I want to say that I don’t think my characters actually make decisions based on what they get from mystical or supernatural sources; looking in that direction indicates a kind of desperation for meaning, but the final answers never come from those places.

Guernica: How Should a Person Be? opens and closes with an ugly painting competition, and Motherhood contains actual reproductions of paintings and photographs. You’ve said that writing about “the history of art” is very challenging for you, but it’s something you want to do. What kinds of space does thinking about visual art open up for you that literature doesn’t?

Heti: Thinking about visual art allows me to think about writing (and how I might write) by way of analogy. If I see what another writer is doing, that doesn’t spark anything in me in terms of how I might write differently. But for instance, if I think about a Richard Serra sculpture as something that a person walks through, then I can think, What would be a book that a person could ‘walk through’?

So for instance, when I was writing How Should a Person Be? I was very interested and did a lot of research into Serra’s piece, Tilted Arc (among other artworks by other artists.) To make Tilted Arc, Serra studied how people walked between two buildings in lower Manhattan, and he traced a sort of arc in the ground which represented the path that most people used to cross the square. Then he put up a huge steel sculpture right along that path, forcing people to walk to either side of it. People hated this sculpture! It was immediately defaced in all sorts of ways. So it’s interesting to think about that hostile interruption of a path that people took intuitively for convenience and think, What might a book be that does that same thing? What would be the path you’d want to interrupt, which people take easily and unthinkingly, and what would you lay down to interrupt that path? This kind of thinking, by way of analogy with art, allows me to think of new ways to write. But if I read a great book, I just think, That was a great book, and that’s all there is to it. I don’t try to use it. The book is a perfect realization of itself. It doesn’t need its techniques to be adapted to another book—a book I might write. That book has already been written in all its perfection. But no one has written Tilted Arc.

Guernica: I recently reread your contributions to Miranda July’s online project “We Think Alone,” but much of your work is about thinking with others. Are there some kinds of thinking that better lend themselves to collaboration and others to solitude? What are they?

Heti: I think political thinking, or any kind of thinking that is about the fate of the many and the conditions of the many, better lend themselves to collaborative thinking. Collaborative thinking allows for different points of views and experiences to conflict and merge. A person will do a much better job of thinking about society and how to make it more equitable, for example, if they are thinking alongside people who have experienced different conditions from their own.

Thinking alone is more a way of creating a personal language out of symbols that are intimate to you, searching for meanings that are personally significant, and putting them together in ways that have the greatest charge or valence for you. One hopes that others will feel the same charge, but that hope doesn’t lead your decisions, primarily.

But I don’t really think of writing as thinking so much as making or playing—sometimes a person wants to play with others; sometimes a person wants to make things alone, and it doesn’t have as much to do with what is the end product you are aiming for, as how you want to be spending your time. Do you want to be quiet? Do you want to learn from others? I am usually involved in several projects at once, some of which involve other people, and some of which don’t, and I move back and forth between them. Sometimes I can’t stand hearing another person’s opinions; there can be too much of the outside world. At those times, I want to work and think alone. What is the place on the other side of solitude, neither with other people, nor alone? Whose place is it, and what might be said from there? I feel more interested in that, these days.

Guernica: If you don’t primarily consider writing as thinking, then where or in what form do you do your thinking?

Heti: I mean, thinking is involved in making and playing, I don’t want to deny that. But that’s thinking about the form of the work, the form of the world and how it should all fit together, more than any other kind of thinking. You’re thinking about what you’re doing, and how to do it. I’m not sure where or how I do my thinking. In conversation with friends? I find it hard to just sit and think something through to the end. My mind goes off in random directions. I guess I don’t know what you mean by thinking. I think all of living is thinking.

Guernica: We read quite a bit about the dreams of Sheila in How Should a Person Be? and of the narrator of Motherhood. How do you understand your own dreams? As prophecy, commentary, criticism?

Heti: I think of dreams as a reality we inhabit, the same way we inhabit a waking reality. We live in both these worlds, and both are so real, but with different rules and atmospheres. I prefer the atmosphere of dream-life, and I feel frustrated by how quickly dreams disappear once I wake up. I don’t interpret my dreams, just as I don’t interpret my waking life. I simply exist in both of these realms, and they pass things back and forth; I don’t know what they give each other, or how. Life often feels to me like a dream; unreal, like anything might happen, and like I don’t understand what’s going on, exactly. I don’t think about my dreams in any way except for trying to remember them, and trying to hold them close to me during the day.