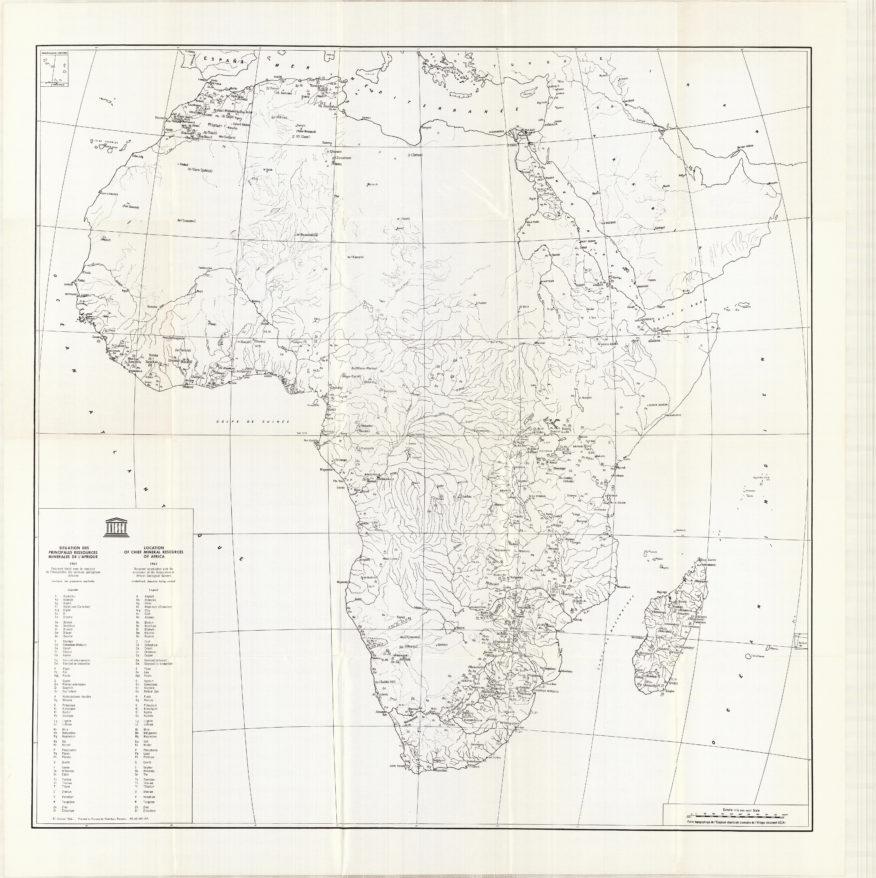

Like most journeys, Shayna Rosendorff’s work started with a map — in her case, a large-format map at the back of a dusty 1963 UNESCO book. Its yellowing page showed natural deposits of mineable minerals in Africa, such as nickel, manganese, copper, gold, platinum, and diamonds. Accompanying the map is this caption: “In view of the greatly increasing demand for minerals owing to the rising world population, higher standards of living, and the working out of many deposits, it is highly important that detailed surveys to determine mineral potential of new areas should be completed well before known resources elsewhere become seriously depleted.”

The caption tells an obvious story about blatant extractivism: Africa’s natural wealth will meet the world’s resource demand. Perhaps less obvious is the story that is told in the visual language of the map itself: besides the veins of rivers and the markings of minerals, the map looks perversely empty — a vast expanse of boundless abundance, readily available for the taking.

Maps often project objectivity, but they are not neutral. Rosendorff wondered how she might manipulate the visual language of maps. What is an image without a certain color? What is the landscape without its minerals?

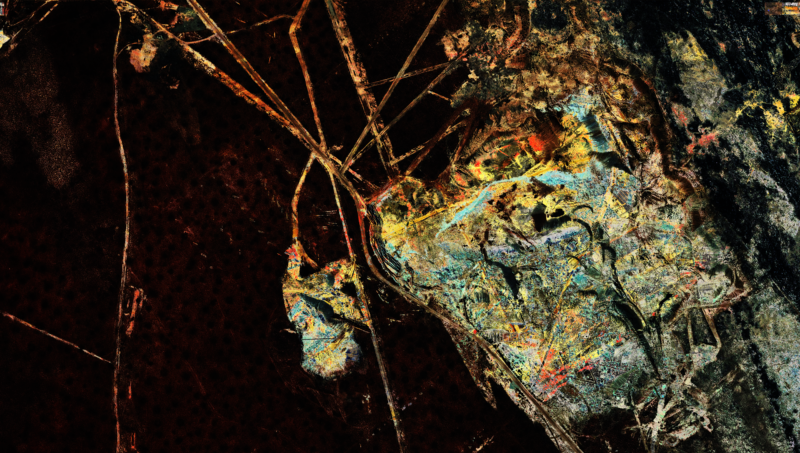

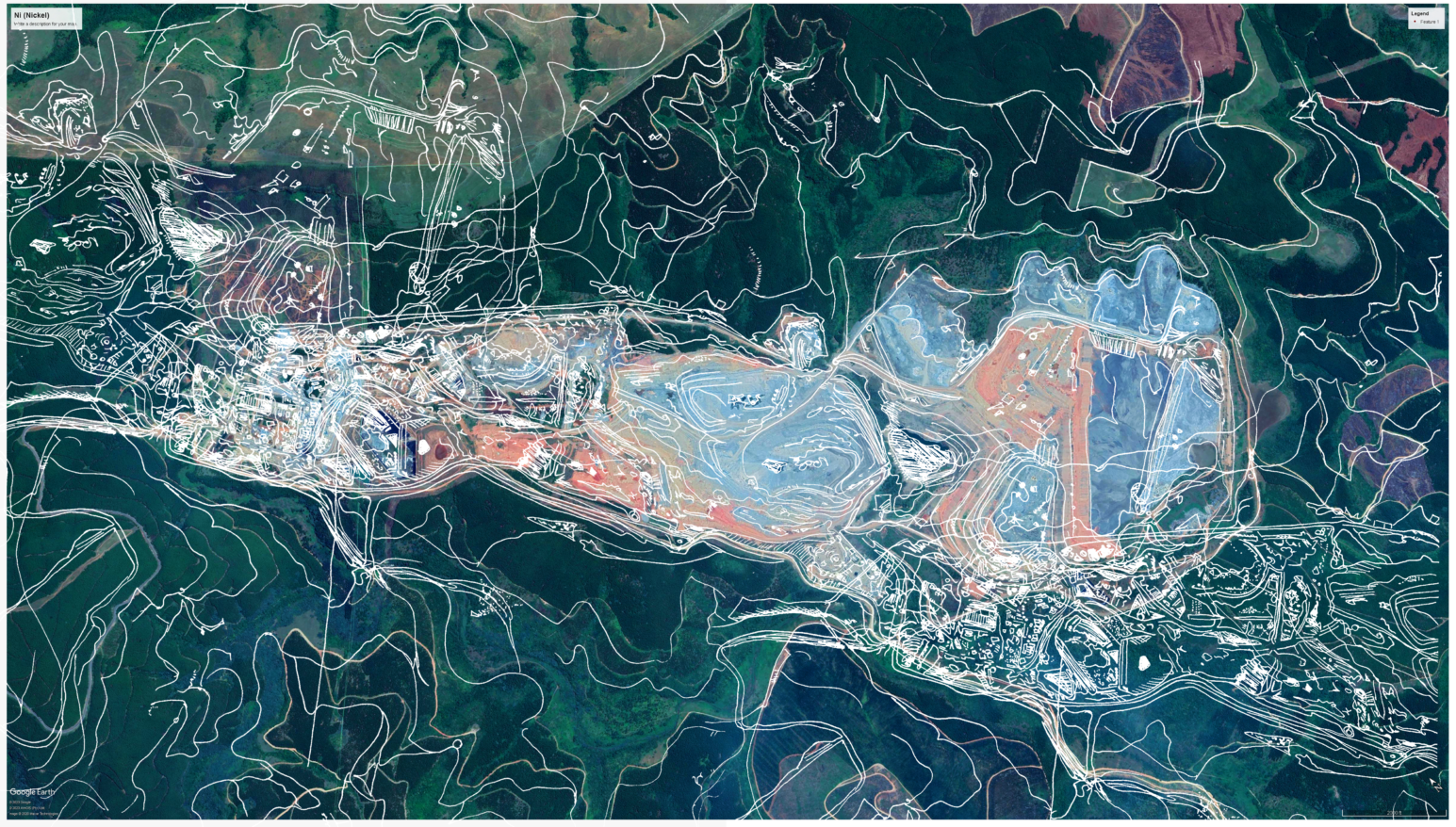

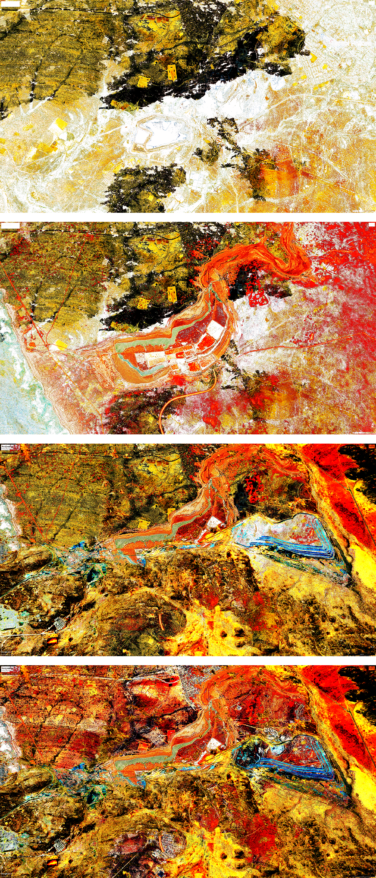

Rosendorff checked the UNESCO book out from the library, set the large map on her desk, and opened up Google Earth on her computer. Using remote sensing data, she mined satellite images for sights and vistas, extracted tones and patterns, and smelted them into new amalgamations. By consciously reproducing the colonial practices that led to mangled minescapes scattered throughout the continent in the first place, she exposes violent resource exploitation in Africa.

The 1963 map was designed to locate places of wealth, but instead it marked places of future devastation. The mines, especially when viewed from above through satellite images, show no sign of any life, yet they feed on it. The ruined lands — scarred hills, poisoned rivers, and open-wounded pit mines — are more than just a metaphor for ruined lives and ecosystems; they are the reason for it. South Africa’s history, in particular, is driven by a ravaging hunger for minerals that has torn apart bodies, families, and ecotopes alike. First diamonds, and then gold and other minerals, drove and defined South Africa’s industrialization. They also guaranteed the stability of the apartheid system, which arguably lasts beyond its official abolishment. As we speak, mining wreaks havoc on human and ecological health.

Walter Benjamin wrote about the Angelus Novus, a painting by Paul Klee: “Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe, which keeps piling wreckage upon wreckage.” This is a story that’s retold across the continent — scars that are left everywhere, visibly on the landscape, and less visibly in social relations and bodies.

Rosendorff charts South Africa’s history of wreckage by layering images of remote-sensing data to represent this one single catastrophe. I spoke with her about her artistic process, ruined landscapes, the power and violence of maps, and how her work creates heterotopic imaginaries that challenge colonial cartographies.

—Vasna Ramasar for Guernica

Guernica: I have a background in geology, environmental science, and human geography, and so when I read the text about your work, I thought, “She’s a geographer!” Tell me, how did your art get into this focus on space and place?

Rosendorff: For the last three years, I’ve been focusing on the politics of land and landscape in various ways. In a previous body of work titled Constructing Space — part of a collaborative project between Wits University and BMW Group — I made miniature sculptures that resembled landscapes and then photographed them to make them look like real, large spaces. I used copper as a medium to create “mountains” and began thinking about what is natural, especially how something that appears natural can actually be man-made. Then I thought about what it would mean to take something that was underground, lift it up, and make it a mountain. I thought, I need to know more about copper and where it came from!

I’m someone who spends a huge amount of time in the library and in bookshops, so when I was looking for more information on copper mines, I went into the Cullen Library at Wits, which is my favorite place. I found the book that became the focal point of this research: A Review of the Natural Resources of the African Continent, published by UNESCO in 1963. I was the first person to have ever taken it out of the library. And then because of the lockdown, I couldn’t take it back because we couldn’t go back to university. So I had this book for an entire year! I spent every day just reading through it and staring at it.

At the back of this book is a huge map of Africa and all of its minerals. I spent time working out what those deposits are and what they looked like, starting in South Africa and working my way north. Then I took this map — that didn’t have any borders, just these lines that show rivers and the resources — and I imposed borders, which felt like quite a violent thing to do, but I needed it for my research.

Guernica: Well, someone did that at the Berlin Conference in 1884, which established the modern boundaries of nation-states in Africa in the so-called Scramble for Africa. So you’re not doing any violence that hasn’t been done already.

Rosendorff: Yeah, I guess so. But it was still nice to see it without its borders. I put all these lines in there and I compared it to Google Earth to match them. Then, I found that quote, about exploiting resources before anyone knew they were there, in the preface. So, though in 1963 South Africa was an independent Republic, it and its neighboring countries were still being framed as countries to be exploited. Although not all of them were independent yet, this book points to the fact that Africa was (and still is) viewed as a resource that is owned by the West to be used when needed. In my mind, it also demonstrates the fact that substantial independence movements throughout Africa in the ’50s and ’60s were not taken seriously.

There’s something really important in the way that old books tell a history better than a history book does, because I’m reading the thoughts and the sentiments of those people in their time.

Guernica: Unfortunately, you’re still likely to see that kind of colonial language now — that Africa is rich in resources, and we need to extract them. But now the language has changed slightly: it’s for the good of African people that we’re going to get them out of poverty through extracting these resources. But just because the language changed doesn’t mean the attitude behind it did. This leads me to wonder, what did you learn when you shifted this story into a visual language — from maps to Google Earth to the landscape pieces you created? What did it reveal to you about what is and isn’t trustworthy?

Rosendorff: I found that the colors of the landscape can’t really be trusted on Google Earth. But after some time, I could tell which was coal, which was diamonds. My original thought was to mine the mines: to cut out the satellite images of those mines, take them out of the landscape to extract them myself and uncover what once was. That got me thinking about the mine as a commodity.

But after going through countless images of these mines that are different and unique, I noticed so many similarities that they just became the same thing. They became a sort of collage, a pattern. These mines keep repeating throughout the continent, and what emerges from this pattern is just how many they are, how similar they are, how similar their stories are.

Guernica: To me, it felt like the big point of what you were making is: it’s not one mine, it’s a story that’s retold across the continent. These are scars that are left on the landscape everywhere.

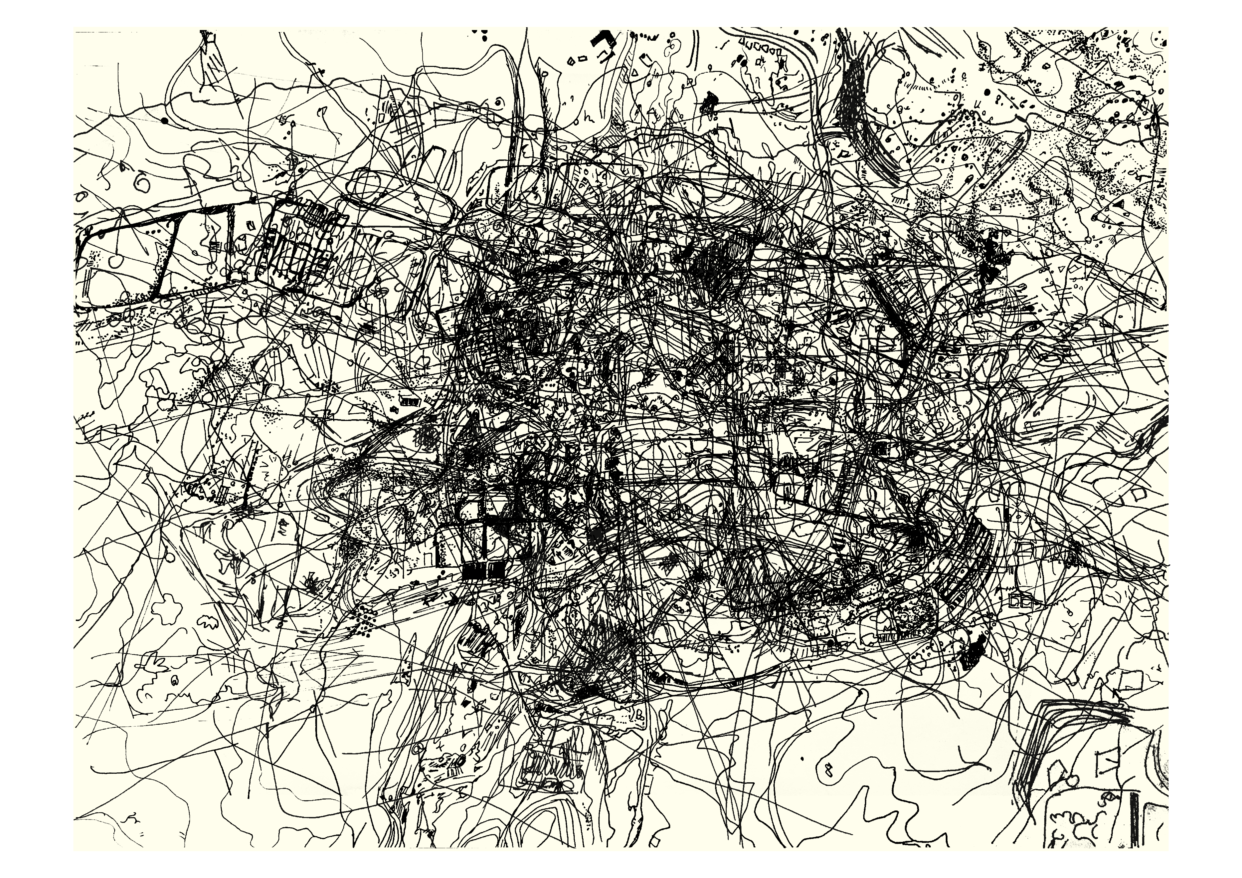

Rosendorff: Yeah, exactly. It’s the collage and the subsequent layering that says so much about the meaning of the work. The process of layering surprised me; it gave me the power of representation, in choosing what was seen and what was not. The more layers you place on top of each other, the less likely you are to see or even remember what was once there in the first place. This is the precise story of the mine — the more layers, the less you see. A map acts as a record that both reveals and conceals history. The presence of these mines shows us the history but also conceals what might have been if the mining had never taken place.

In 2020 we saw a major shift to the digital space — these maps exist in that space, and never outside of it — but, although they only act as digital representations of the space, they take on a level of truth because as humans, there is a trust that we place in the representations of things we are unable to see. This act of repetitive mapping ends up erasing itself. I digitally laid all of my drawings on top of each other, to the point where I could not make out what they were. It became quite a dark image, and you couldn’t see it anymore. And that was the whole point! It takes its power away.

Guernica: I like that idea that mapping erases itself, and it takes the power away. But there’s also a darker way to view it as well, as the ecological impacts of these mines also layer on top of each other. And then they don’t erase each other, but they become part of the landscape. I grew up in KwaZulu-Natal, and I remember, as a kid, driving with my family from Durban to Johannesburg, passing through the East Rand of Johannesburg, and you see all these mines. I have such a vivid recollection of being awestruck: whoa, that’s just massive and so alien! And now, as an adult, when I go back to Johannesburg, I drive through that landscape all the time, and it doesn’t evoke the same reaction, because it has become so normalized.

Rosendorff: Yeah, exactly. At the end of my degree last year, I wrote my research paper on the trees of Johannesburg and how they act as visual representations of how the mining industry created class divisions of the city that still exist today. They represent the politics of space and privilege. That’s also something that you just drive past and shrug, but they are actually embedded with so many complicated histories.

There was a particular nickel mine — I think I drew it like 50 times. I just was so taken by its appearance. It was just so beautiful. I was so confused why I thought it was beautiful, because it’s so messed up. If I were to see it in person, it would be really ugly. But, from where I was viewing it, it was also strangely magnificent.

Guernica: In political ecology, we need to embrace the ugliness and ruination as part of our history. That’s how we take back these landscapes.

Rosendorff: Yeah, it’s hard to appreciate something that has ugly parts of it.

Guernica: Last year was awful by most standards, yet you clearly found a way to express your creativity and make art in unusual circumstances. What did you learn from doing research this way and doing it in a pandemic?

Rosendorff: My understanding of my own access and mobility grew when I sat at home and had to think about how else I could access a place. Before, I could just go there. At the same time — I mean, who has access to Google Earth? It’s not like everyone can do that either. But it’s just about adapting ways of thinking.

Guernica: I think that is, for me, one of the most important things of the human spirit: how truly resilient we are. We try to find ways to get by, but also to flourish — not just to survive.

Rosendorff: It’s also about the experience of a piece of artwork. Most of my peers made something physically and then photographed it so it could be seen on a computer screen. My work was made completely on a computer screen and never really existed in the real world until the end, when I drew them.

Guernica: Tell me more about the political conversations you want to open up with this work.

Rosendorff: There was something I once read about landscape art — I think it was a European idea — that said that when landscape paintings would be put up in houses, it meant that they owned the place in the painting. Landscape originally was meant to be a representation of what you owned.

When I was making my small miniature landscapes for the BMW Group and Wits collaboration, those landscapes were completely mine, without any contestation. But working with mines is different. These mines are in fact very contested. Land ownership and historical dispossession of land in South Africa has still not been sufficiently reformed. I’d say they are even more contested than other spaces because of the mineral value that they have.

When you walk into art school and say: “I want to make a landscape,” people roll their eyes and say, “A landscape is the most basic form of art.” But it’s actually the most political — and especially where we are, in South Africa. You can’t get something more contested and more political than land.

Guernica: This touches on some pretty bleak discussions in South Africa’s history about the migratory labor history of the country, the division of families, but also the ecological devastation that so many families and communities who live around mines have to deal with. Those political questions are really important. If I may play devil’s advocate, but also maybe just a little bit stereotyping, since we’re both South African — as a young white, Jewish woman in Sandton, what compelled you to touch on this?

Rosendorff: The one thing that I am constantly aware of in my work is my white hand. There is this visual, both artistically and metaphorically, of the white hand that comes and saves, and the white hand that comes and takes.

When I was filming the making of the miniature landscapes, it captured my hands as they were making the sculptures. Regardless of who I was, my history, and what I was trying to say, that white hand represented much more. You can’t make artwork without political connotations. So I educated myself as much as I could on what these things meant and how they impacted people. I’ve faced criticism constantly for being who I am and speaking about what I had, but land is a South African issue that everyone needs to talk about. And if I can be one extra person bringing attention to the fact that the land and the land distribution in this country is still so unjust — that’s a good thing, because it impacts all of us in completely different ways.

Guernica: For me, what you’ve done is compressed the space of the continent and brought it down to one node. However, the mines themselves also compress time; they are not only the “present,” but extend into the past and the future. They contain the history of mineral exploitation — you are working from a 1963 UNESCO report — but they are still present today, and those mines are still going to be in the landscape for quite a while into the future. Your images also seem to contain this continuity between past, present, and future — and also open up conversations about agency, about resistance.

Rosendorff: I once talked to an architect who described how territory is length, breadth, and height. Representing things from above produces completely flat images. As you say, they’ve been compressed, creating new realities and obscuring others — because they cover up what this space once was, who lived there, who traveled through there, and what events took place there. That 1963 map only represents one dimension: exploitation. My work then abstracts that even further.

Someone said to me once that viewing my aerial images desensitizes them from the atrocities that happen in the mines, which was interesting, because in a way, I am. I am aestheticizing something violent. You can’t see the violence looking at it from above — it’s just a couple of lines and a couple of circles. It becomes a bit of a voyeuristic experience, traveling above Africa and staring at things that I couldn’t have had access to before. In a way, I am also desensitizing the viewer to the violence that took place on the ground — something that all maps do.

As I mentioned earlier, context, bias, and personal history play a huge part in one’s understanding of and interaction with the world around us. For me, resistance comes from challenging our taught understanding of the world around us. In Johannesburg, a tree is not a just a tree; it is a representation of a classist mining town. In the same way, a map is not a just a map; it is a representation of years of structural oppression and violence that reshaped the landscape until it became completely altered.

Guernica: Yeah, there are many theories about power, and how power works. Something is most powerful when it’s invisible — when people don’t even know that it’s operating so we automatically assume we have to behave a certain way. If we are to challenge and subvert the system, we have to reveal what is made invisible, and open up the conversations to redress past and present damage and shape the future differently.

Rosendorff: Absolutely. For me, the purpose of this project was twofold. The first was to gain a deeper understanding of the impact that humans have had historically, and still have, in shaping and redefining nature. The second was to instill a sense of criticality into the minds of my viewers — to not take anything at face value, because the way the world is structured has a meaning deeper than its aesthetic quality. And that meaning often has violent roots that we cannot see, but we still can try to understand.