On Shawn Walker’s thirteenth birthday in 1954, a neighbor in Harlem gave him a Brownie Hawkeye. It was his very first camera. He carried it everywhere, shooting family dinner parties, kids hanging out on 125th Street, and church ladies parading in their Sunday best, their hats reflecting the sunlight. So began an over five-decades-long career as a photographer and photographic educator—or, as Walker describes it, his life as a “cultural anthropologist.”

The camera saved him, he later reflected, from the pull of the streets. His parents were middle class, but father died when he was a teenager, and Harlem was in the grip of a heroin epidemic. “I needed to get my act together,” he said. When a friend told him about a photo group—guys who were a bit older, had been in the service, worked in labs—Walker joined. Within a year he was working as a photographer for two newspapers in Harlem. It was the time of the Black Arts Movement, the era of Amiri Baraka (then known as LeRoi Jones) and the Black Panthers. “I was the guy with the camera,” he said. “They let me in because they knew me, and they trusted me.”

In 1963, two Harlem-based photographic groups merged, and Walker, then 23, became a founding member of Kamoinge Workshop, now the oldest black photographers’ collective. Kamoinge met every Sunday in members’ houses for hours of constructive critiques, followed by more hours of food. “You had to show up with work in hand,” he said.

Walker describes Kamoinge as “his Sorbonne,” although he admits, with a smile, that the relationships forged there were so intense they broke up marriages and partnerships. Through Roy DeCarava, its president, the group soon produced two portfolios of work that were acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in the 1960s. In 1973, Beuford Smith, a Kamoinge member, launched the Black Photographer’s Annual; Walker served as one of its Picture Editors from 1973 until 1980.

Walker is now 77. Dressed in a black Thelonious Monk t-shirt, he showed me through his rambling ground-floor apartment in Harlem—part home and part studio, plus a library crammed full of books. Although he went back to school to receive a BFA degree from Empire State College in 1987, he is largely self-educated: Life, Time, and Look Magazines, and books about French and European painting and African art. He cites as major influences the work of Charles White, Romare Bearden, Jacob Lawrence, and Henri Cartier-Bresson.

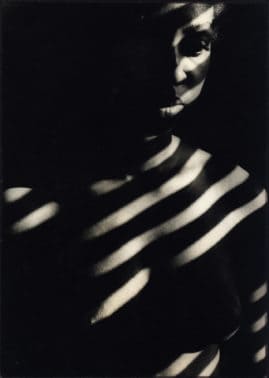

He doesn’t attribute his style to any particular photographer or movement. “My race,” he said, “gives me my artistic point of view.” It is an aesthetic that goes beyond the vision and images of a traditional photo-documentarian, and makes extensive use of shadows, light, and Walker’s own talent for finding the unusual in everyday life. “When I came out of my mother’s womb, I was black. Blacks are so damaged in the United States,” he said, but “we should not be afraid to be black.”

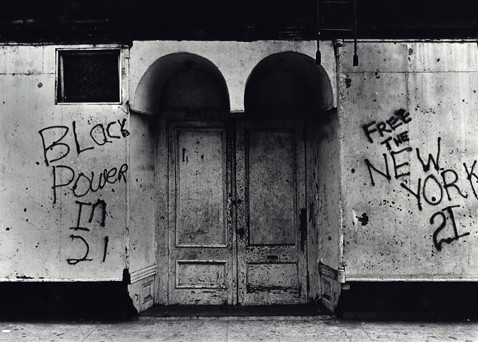

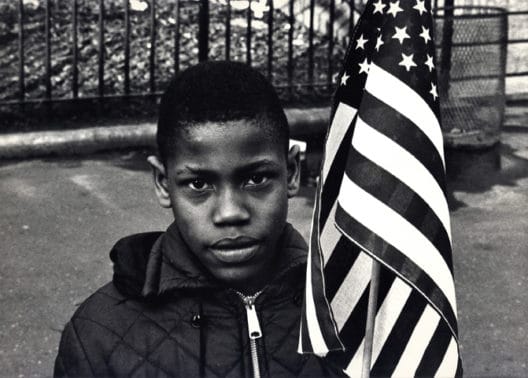

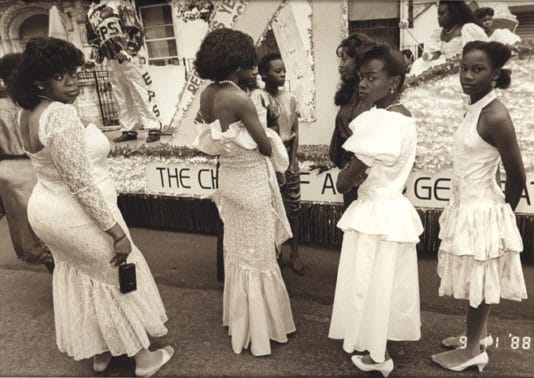

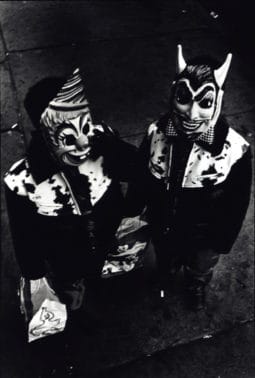

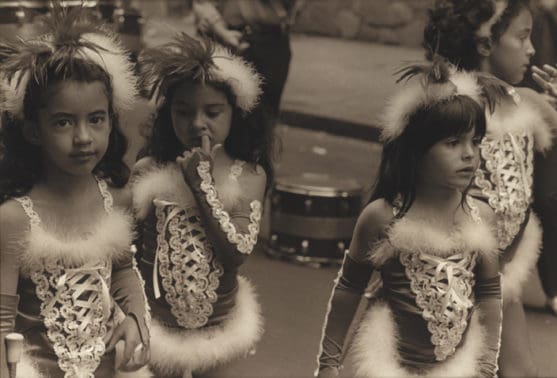

The first solo retrospective of Walker’s work from the 1960s through the 1990s, which is currently on view at the Steven Kasher Gallery, sheds new light on the powerful trajectory of his career. There are black-and-white vintage Harlem photos that he shot, developed, and printed in the 1960s and 1970s: a black boy, his eyes fixed on the camera, the light reflecting off of the silver zipper on his winter jacket, holding an American flag; a Harlem doorway on 116th Street, framed on either side by the words “Black Power In 21” and “Free The New York 21”; three young women outside a church, dressed for their communion, each holding a floral nosegay with dangling white satin ribbons; two devils from a Harlem Halloween parade; four young girls in a Puerto Rican Day Parade, one biting her nail; and four women dressed in white in a Afro-American Day Parade on 112th Street, three of them eyeing the camera, clearly caught unaware. “I’m not a photographer who engages people,” Walker said. “I don’t want people to see me.”

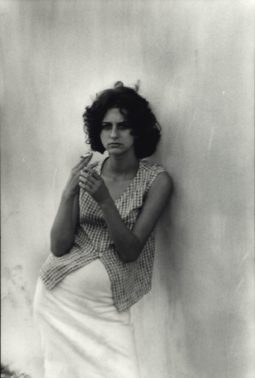

Another reluctant subject, from his 1968 Cuban series, stares at us: a woman caught by the camera, leaning on a wall, smoking a cigarette. Walker went to Cuba to do a film for the Third World Newsreel. When he returned to the States, he said, he was blacklisted, and subsequently had to travel to Guyana in 1969 and 1970 to find work.

Walker does not shoot single images of things, but rather follows topics for years. He has been obsessed with ethnic parades for decades (recently shooting them in color), and with baptisms, jazz, and city walls, where flyers peel off over the years to create ad hoc historical montages. He is in love with found images, seeing a face in a plywood knothole and an abstract design in a manhole cover. He likes strong colors and heightens them in his work, but otherwise does not manipulate the images.

While Walker knew and admired James Van der Zee, the renowned Harlem portrait photographer, Walker himself does not like taking portraits. “I want people to look like themselves,” he said. His art is an effort to capture the essence of his subjects through subtle lighting and through his remarkable attention to detail.

He is increasingly attracted to abstraction, finding faces in found objects on walls, sidewalks. Recently, he has been shooting video: concerts, political events, and interviews. “I am trying to preserve the culture that I am exposed to,” he said.

Walker sees himself as an activist of a sort. He once participated in a march in Cicero, Illinois, a suburb of Chicago rife with racist sentiment, where he realized that the picket line was not for him. He wasn’t willing to lose his life that way, he said. “You need to figure out how to be an activist. Some people are on the front line. Some people make signs. You need to figure out how you can best move forward.”

Evidently, Walker did just that.