I grew up on a farm. The stone wall snaked the boundaries of my family’s fields and the neighbor’s tree line. I remember monkeying my way to the highest limb in the crabapple tree by the small pond just down the hill from our farmhouse. The wind would brush my hair back and bring about an elevated sense of being and connection. Youth sheltered me from the complexities of farm life and filtered the reality of an outside world growing different from the rural existence my extended family was living.

Taxes on land were high and locals were driving in droves to the supermarket for food wrapped neatly in anonymous, sterile plastic-covered packages. Before we knew it, we were losing our foothold in the idealistic endeavor of self-reliance on a family farm. Farms require land and hands. We had both, but times were changing and we weren’t.

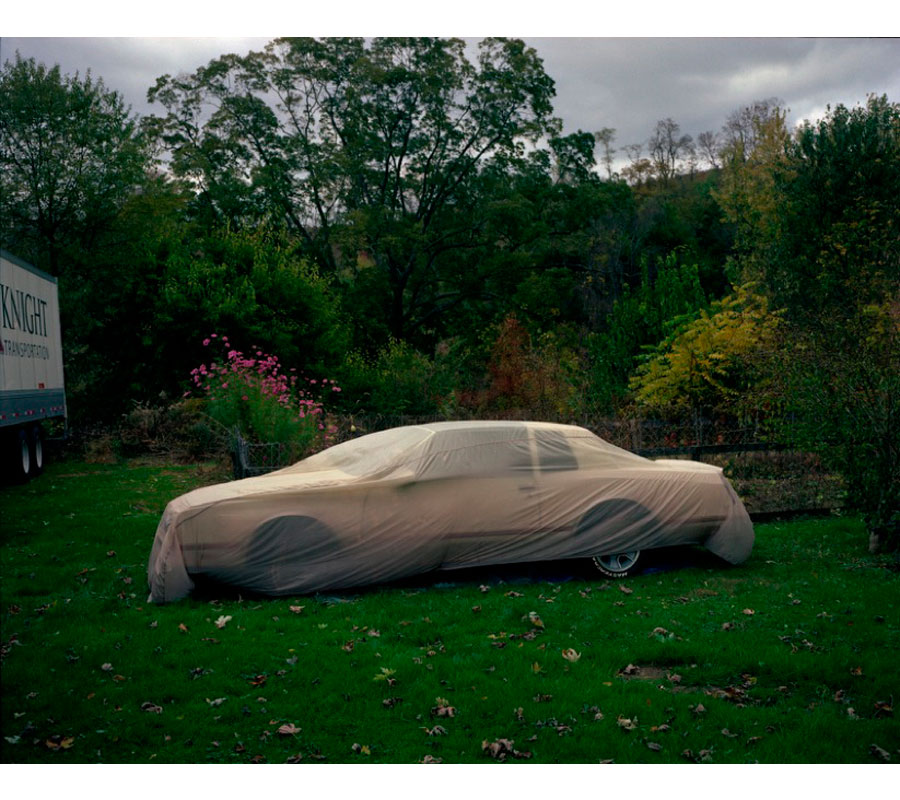

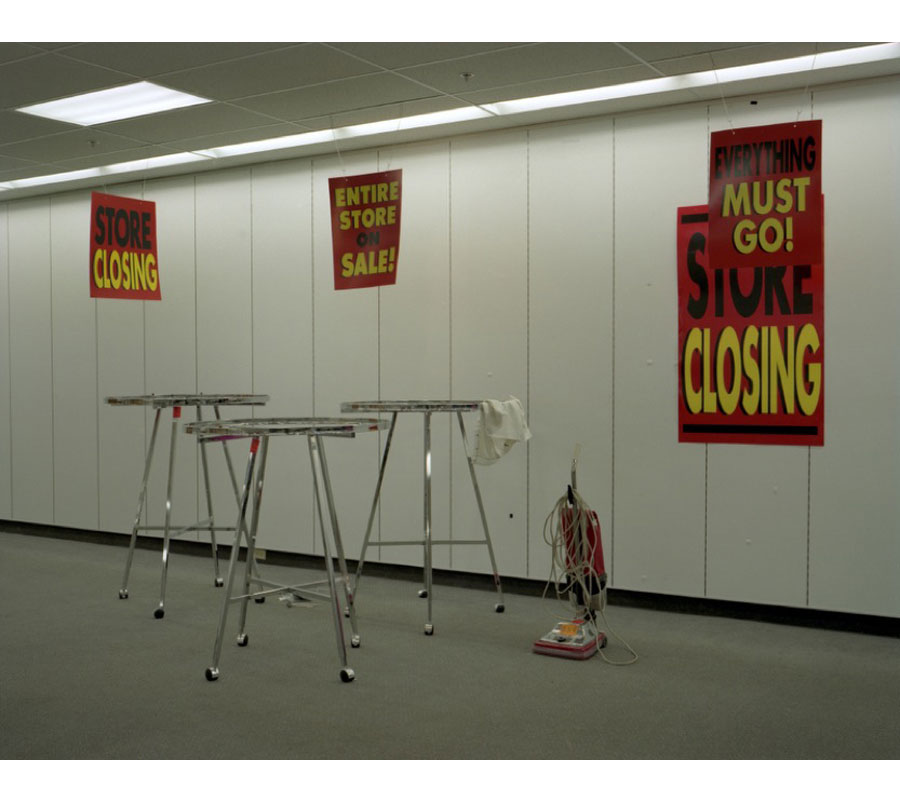

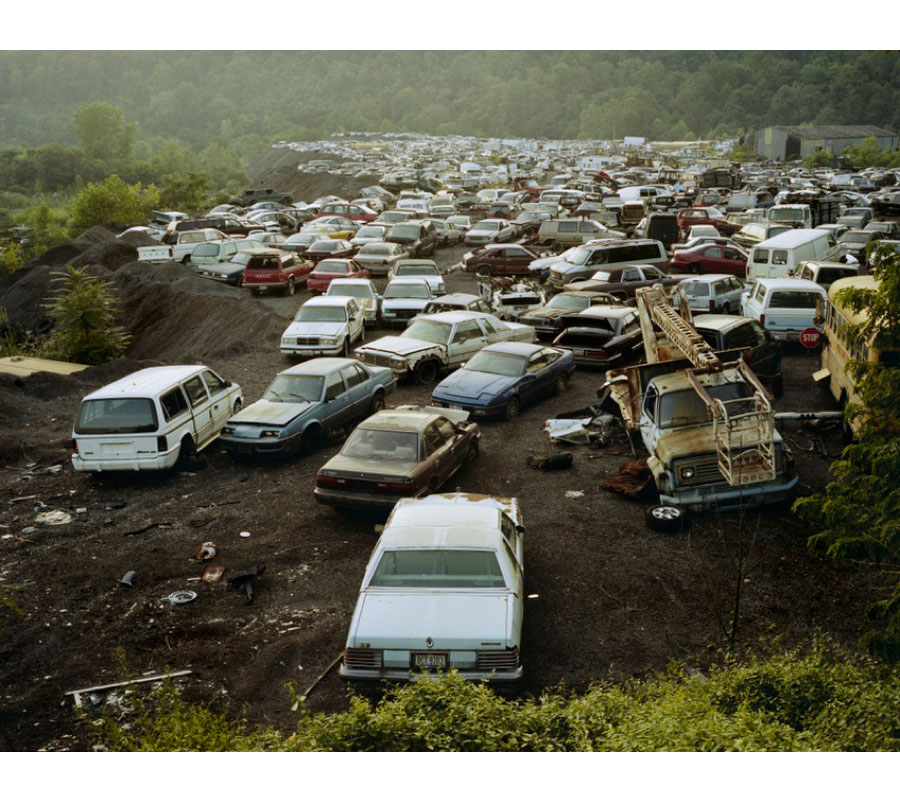

After the loss of the farm to the bank, our family separated. We went in the direction the economy and our faculties would allow. Separated by distance, we soon became distant. Our immediate problems became our problems alone. Our desires became our desires alone. An extended family tree, once connected to its trunk, slowly had its limbs torn off by an unexpected storm. We were all dissolving into the great American experiment in capitalism, a mixture of failed aspirations and dream chasing.

After college a friend gifted me a copy of Wendell Berry’s The Unsettling of America, and from this I began to understand the connection between my family’s loss and our country’s failures.

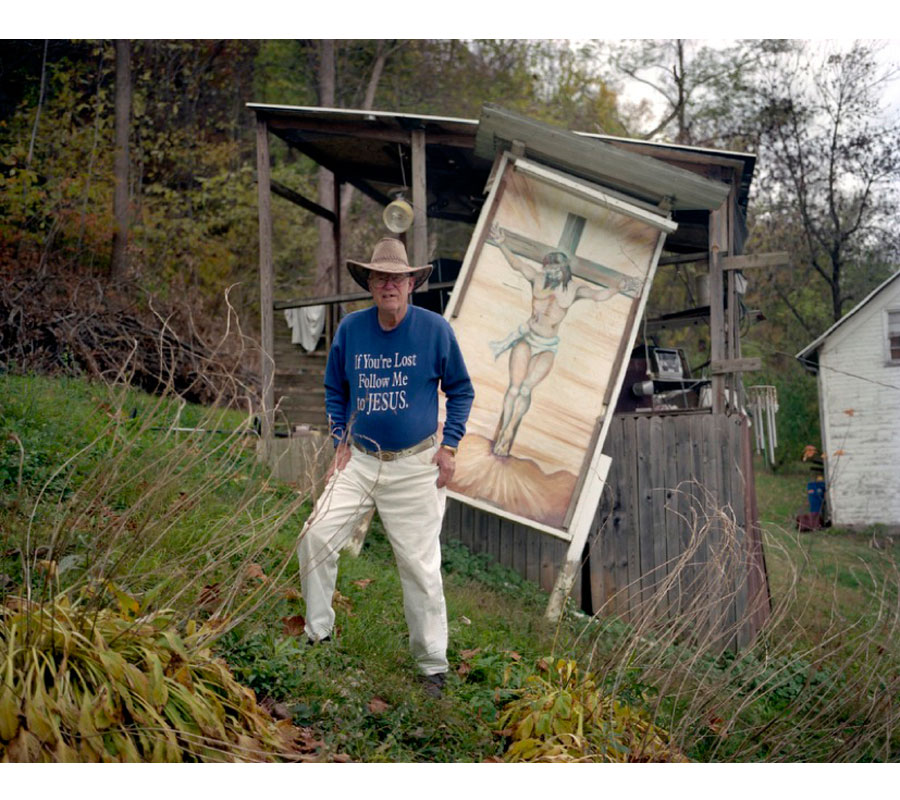

So I found myself traveling through the towns along the Ohio River, from Pittsburgh to Louisville, on a journey in search of a cause. I was looking for a reason why things had gone awry, not only in those river towns but also in my own history. I consumed Berry’s words over and over again, allowing them to pass through me and process my observations and recognitions of humanity.

As with all human endeavors, this project has uncovered a society fraught with contradictions.

It was as if the river itself had dried up.

I was in search of what had settled.