Theory heads and lit lovers, have you ever wanted to get into the Da Vinci Code only to be deterred by the bad writing, shoddy research, and the possibility that someone might see you reading it? Have you noticed that Dan Brown’s protagonist is a “professor of symbology,” then complained to your friends, when they asked if you’d like to join them for a screening of Inferno, that there is no such field? Have you pulled your hair out wondering why Dan Brown seems never to have heard of semiotics?

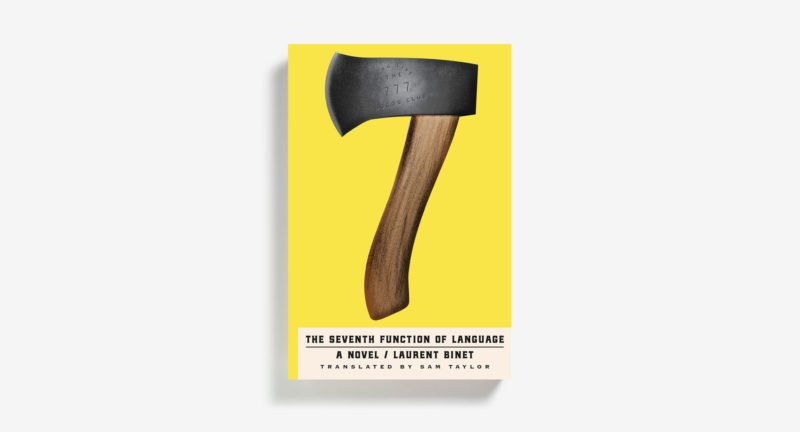

Have you dreamed of a better world, where such a globe-trotting conspiracy novel might feature your favorite continental theorists front and center? Have you wondered what would happen if Noam Chomsky and Camille Paglia got high and made out at a Cornell frat party? If you’ve answered yes to any or all of these questions, then The Seventh Function of Language is the book for you. Not since Jeffery Eugenides’s The Marriage Plot has a book of commercial literary fiction been so prone to dog-earing at the hands of a first-year comparative literature major. And even if you fit none of the categories above, know nothing about continental philosophy or semiotics, and can’t tell Saussure from a cup and saucer, you still have a pretty high chance of enjoying Laurent Binet’s new novel.

On March 26, 1980, French philosophy and literature suffered a great loss: Roland Barthes, professor and author of such critical texts as Mythologies (1957 in French, 1972 in English) and Camera Lucida (1980 in French, 1981 in English), died, a month after being struck by a laundry truck. For Laurent Binet, it became the perfect jumping-off point for a novel. What if it wasn’t an accident? What if Roland Barthes was murdered? But then, why would someone murder a literary critic, a philosopher, a semiotician? Answering such a question is where Binet’s flair for imaginative fiction lies.

The Seventh Function of Language begins with Barthes’s accident, and since he had been lunching with presidential candidate Françios Mitterrand just moments before, a cop, Superintendent Jacques Bayard, is called in to investigate any possibility of foul play. Bayard, a no-nonsense, conservative civil servant who has seen some dark events while serving in Algeria, tries to question Barthes’s friend, the philosopher Michel Foucault, after one of his classes at the Collège de France. It doesn’t go so well, but it’s delightful to read Bayard observing Foucault’s lecture, during which he wonders whether “this guy get[s] paid more than he does.” Bayard tries to read some books by and about Barthes, but, angered by the jargon and obtuseness of the texts, he heads off to another university, Vincennes, to find a lecturer on semiotics to assist him. This is where we meet Simon Herzog, mid-lecture on the semiotic signs comprising the world of James Bond. Bayard is a little more amused than he was by Foucault. As a test of the practical applications of semiotics, Herzog performs an accurate Sherlock Holmes-type cold reading of Bayard based on his appearance, and a partnership is formed. Herzog is conscripted, at the insistence of President Giscard, to aid in the investigation and question all the intellectuals of Barthes’s social and professional circles. From here the narrative takes off, from the parlors and cafés of Paris to the tense, politically charge climate of Bologna, with casual violence from the left and the right, and even further, to the exotic quaintness of Ithaca, New York, before moving to Venice during Carnival, with macabre twists and turns straight out of Nicolas Roeg’s 1973 film.

Herzog ultimately becomes our hero (and a mouthpiece for Binet), but he and Bayard play out the buddy-cop dynamic quite well. It’s one of many cultural tropes the book embraces along the way, at some turns James Bond and others James Bond parody. One might call some of these tropes mythologies of petit bourgeois culture, or semiotic signs, but you would have to already have geeked out on Barthes’s work to do so. But, regardless, Herzog has, and Binet has, and Binet is going to toy with the reader all the way to the end, refining the exposition about semiotics with which the book begins down to the experience of semiotic signs where the book ultimately arrives.

Binet performs the wonderful magic, akin to an ideal professor, of making these big ideas clear, interesting, and fun. The average reader might not get every inside joke, or be as amused by the shenanigans of France’s intellectual elites as Binet is to write them (or I am to read them, but I’ve got a doctorate in comparative literature and the student loans to prove it), but by the end of the book, they will have a solid understanding of the fundamentals of semiotics.

Laurent Binet is only forty-five years old and his second novel in English confirms not only his formidable deftness as a novelist, but also his surfeit of knowledge on a wide array of subjects. His first novel, HHhH (FSG, 2012), which was also translated by Sam Taylor, took us into meta-fictional territory of Milan Kundera, Italo Calvino, and other European postmodernists to tell the tale of Operation Anthropoid, the 1942 assassination, in Prague, of Nazi officer and Holocaust architect Reinhard Heydrich by two Czech resistance fighters. Of course, in line with the other writers and the gist of meta-fiction, Binet also told us the tale of trying to tell us the tale of Operation Anthropoid.

In The Seventh Function of Language, the authorial voice is far less present than in HHhH, and once the book starts moving into thriller territory it backs away even more. Binet plays a masterful game of form and function with this technique of meta-fiction. Barthes was a disciple of Ferdinand de Saussure’s brand of semiotics, but also followed the work of Russian linguist Roman Jakobson, who wrote about six functions of language. In Binet’s novel, Herzog and Bayard stumble upon a possible secret seventh function that Barthes has gleaned from Jakobson’s work, and it appears to be worth killing over. This function would be performative, and might give the speaker power over his audience similar to the God of the Bible’s “Let there be light.” With less of the authorial voice—inserted occasionally to provide doubt and remind the reader that this is very much a constructed novel—and an acceleration of a thriller-type plot, Herzog can’t help but follow his semiotic training, and begins to experience the anxiety of wondering if he is actually in a novel. He looks out from the text, an interpreter, while we experience him within the text. He, in turn, suspects that we are watching him, fomenting more anxiety.

When it was released in French in 2015, L’Express called the book “the most insolent novel of the year,” and while I don’t know all the books that came out in France that year and can’t confirm the superlative, “insolent” is a wonderfully accurate word. Binet is having a lot of fun with history and these hallowed historic personages. Most every scene with Foucault involves sexual favors from a North African gigolo, and of course there’s the time we see him freaking out on LSD at a BDSM club in Ithaca, New York. Jean-Paul Sartre, Julia Kristeva, her novelist husband Philippe Sollers, Louis Althusser, Jacques Derrida, Gilles Deleuze, Felix Guattari, Paul de Man, Gayatri Spivak, Umberto Eco, Franco “Bifo” Berardi; they’re all here, and it’s not just the continental philosophers. In the book’s third section, the narrative takes us to Cornell University and the continentals get to square off against some American (and American-based) analytic philosophers like John Searle, Noam Chomsky, Camille Paglia, and Morris Zapp. Even Judith Butler, at the time just a grad student, makes an appearance. Not to give too much away, but one of the most laugh-out-loud sections of the book for the philosophically well-read is a Deleuzian sex scene on the dissecting table of a seventeenth-century amphitheater where Herzog and his paramour refer to each other as machines, and their copulation as an “assemblage.”

To begin this review I mentioned Dan Brown’s bestselling series but the more fitting comparison is the work of Umberto Eco, who, not coincidentally, finds his way into The Seventh Function of Language. Eco was the king of learned thrillers, the highbrow yarn, and produced several to great success while also writing brilliant academic studies of language and literature. Binet knows his Eco and knows he couldn’t possibly have written this book without him, as a character or as an inspiring literary trailblazer. While Herzog and Bayard question Eco in pursuit of Roland Barthes’s killers, Eco is struck with a vision that the savvy reader knows will lead him to write his first bestseller, The Name of the Rose. Is this the insolence L’Express is referring to? No matter how crazy the situation we find these historic characters in, it’s hard not to see a great deal of reverence behind Binet’s erudition.

The Seventh Function of Language is a great big joke of a novel, with enough physical comedy, action, adventure, linguistic tricks, puns, meta-jabs, asides, and winks to constantly keep the reader interested and rolling along, all while some of the greatest minds of the last half-century are punished, pilloried, and parodied. After all of that fun, we can pretend we are a little smarter during cocktail-party conversation name-checking and jargon-dropping. But be careful, as Binet is as tricky with his reader as he is with his characters; all his historical facts should be checked before they’re publically defended. There is always Herzog’s advice when he comes to terms with his fictional anxiety:

He must deal with this hypothetical novelist the way he deals with God: always act as if God did not exist because if God does exist, he is at best a bad novelist who merits neither respect nor obedience.

Lucky for Herzog, and for us, Binet is very good.