A striking show of sculpture from 14th century Europe to the present, Like Life: Sculpture, Color, and the Body, currently on view at the Met Breuer, is full of surprises. How, the show asks repeatedly, did artists over the centuries depict the human body? Works of art that we expect to find in art museums are juxtaposed with much more jarring examples—in many cases, objects not traditionally seen as art at all. There are casts taken from real bodies; paint applied to works of art to imitate flesh tones. There are works with human blood, hair, teeth, and bones.

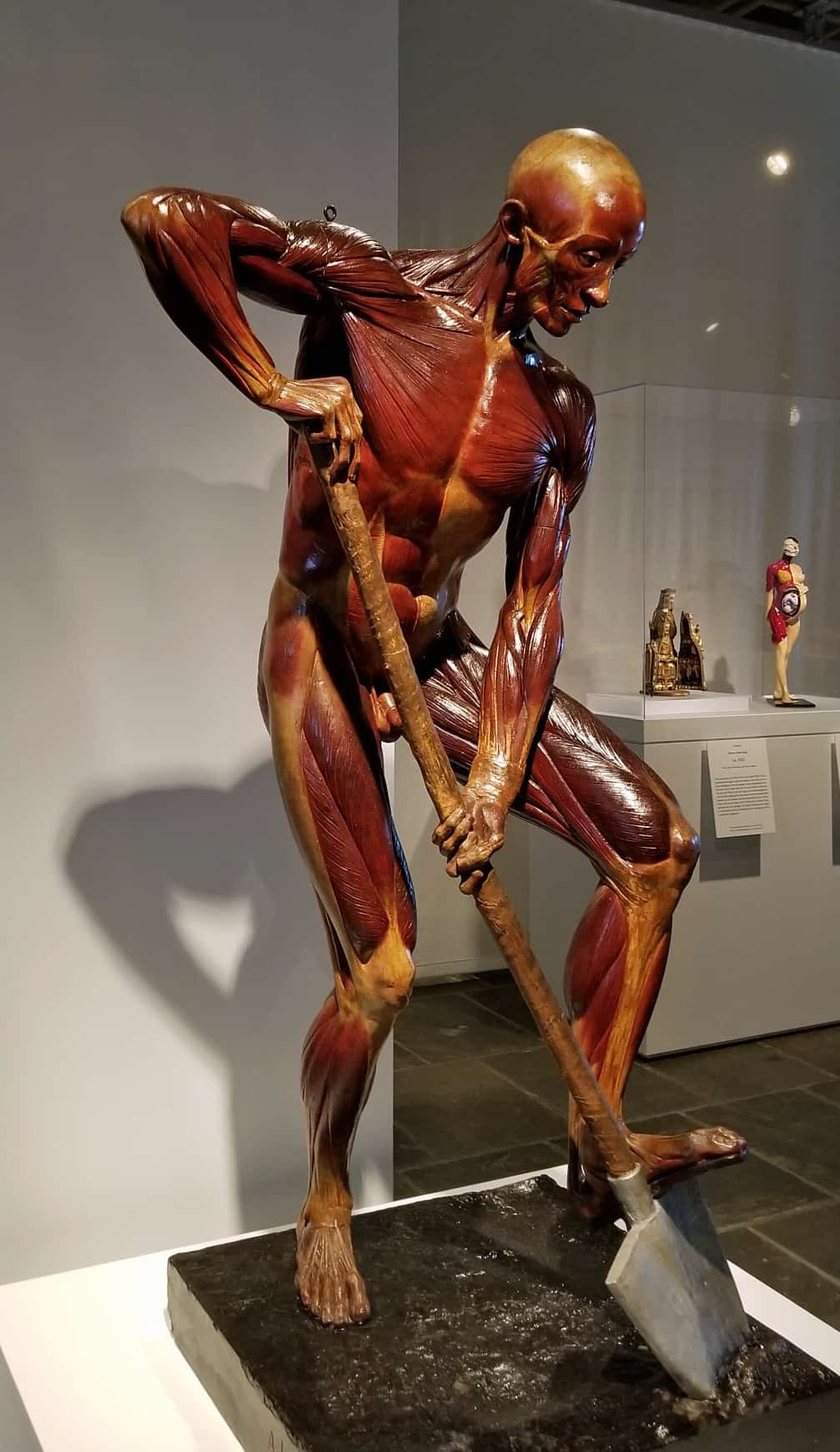

One of the most shocking is The Digger (1857-1858) by Alphonse Lami, where the flayed figure’s (écorché) life-size body is so realistic that we see all the details of his musculature. He is leaning on his shovel but he hardly seems to be working. His body is painted red, with a sheen that radiates from what seem to be medically delineated tendons. The Met Breuer’s website reminds us that although most écorchés were created as anatomical teaching models for students of painting and sculpture, Lami “conceived of this figure as a genuine work of art, exhibiting it at the Parisian Salon of 1857 and signing its bronze base before it was subsequently displayed at the Académie des Sciences.”

The timing of my visit to Like Life was fortuitous. I was on my way to Italy with friends, one of them Professor Bert Hansen, a historian of medicine, whose research trip involved visits to anatomical theaters, medical museums, and archives, which housed collections that journalists rarely saw.

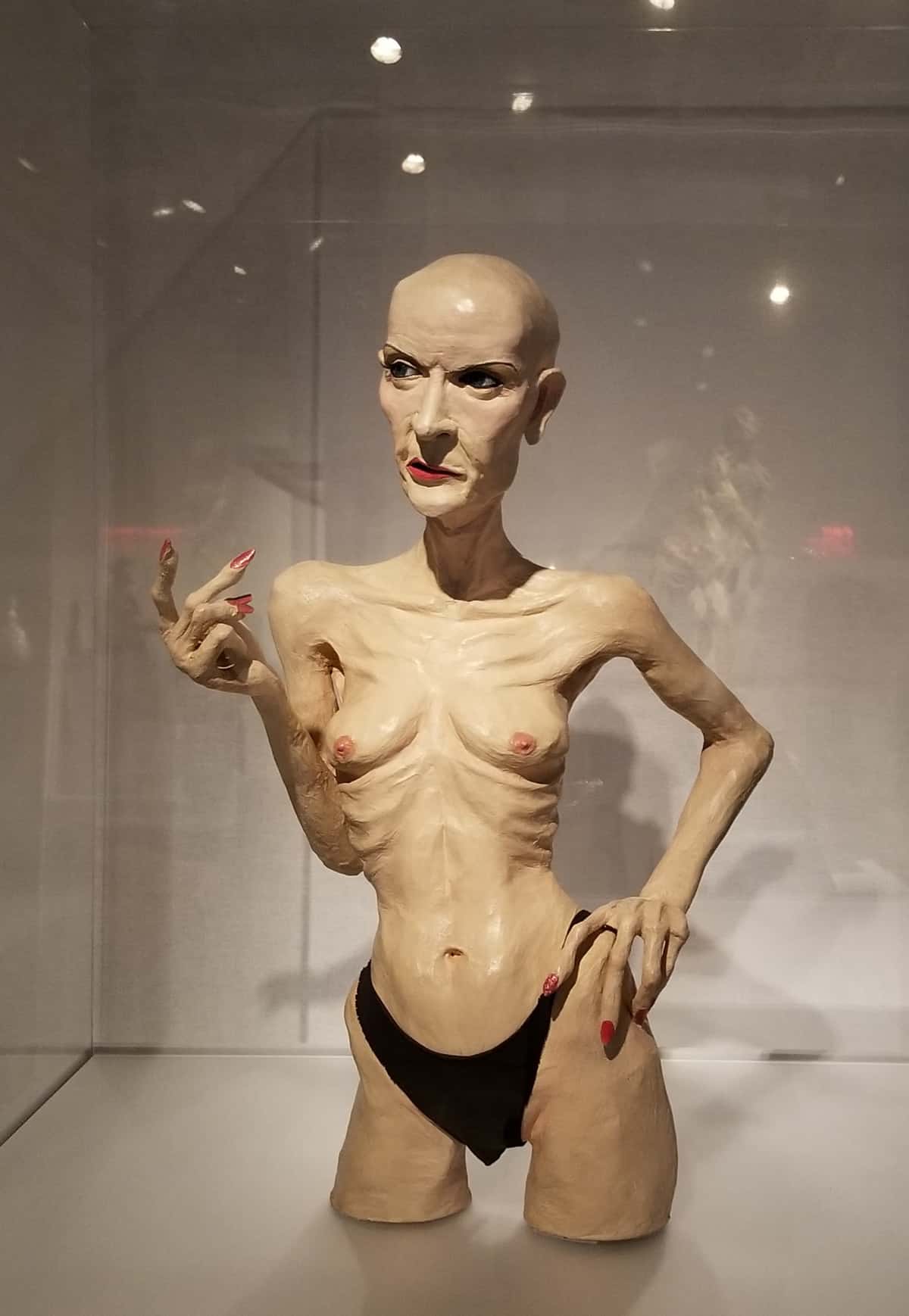

Before Italy, though, I made a short stop in Pittsburgh and saw It’s all about ME, Not You, the Greer Lankton installation at The Mattress Factory on the city’s North Side. The bald-headed doll-mannequin on the posters for the Like Life show in New York was actually a Lankton work: a papier-mâché doll of the performance artist Rachel Rosenthal, which was once hung, fully clothed, in a store window in the East Village. Hairless, her rib bones protruding from her emaciated chest and harshly made up with red lipstick, arched eyebrows, and long red nails, the androgynous figure stares off into the distance with a stern, sad look. Here is another exhibit that focuses on the human body, in this case on Lankton’s, and on her life as a transgender woman.

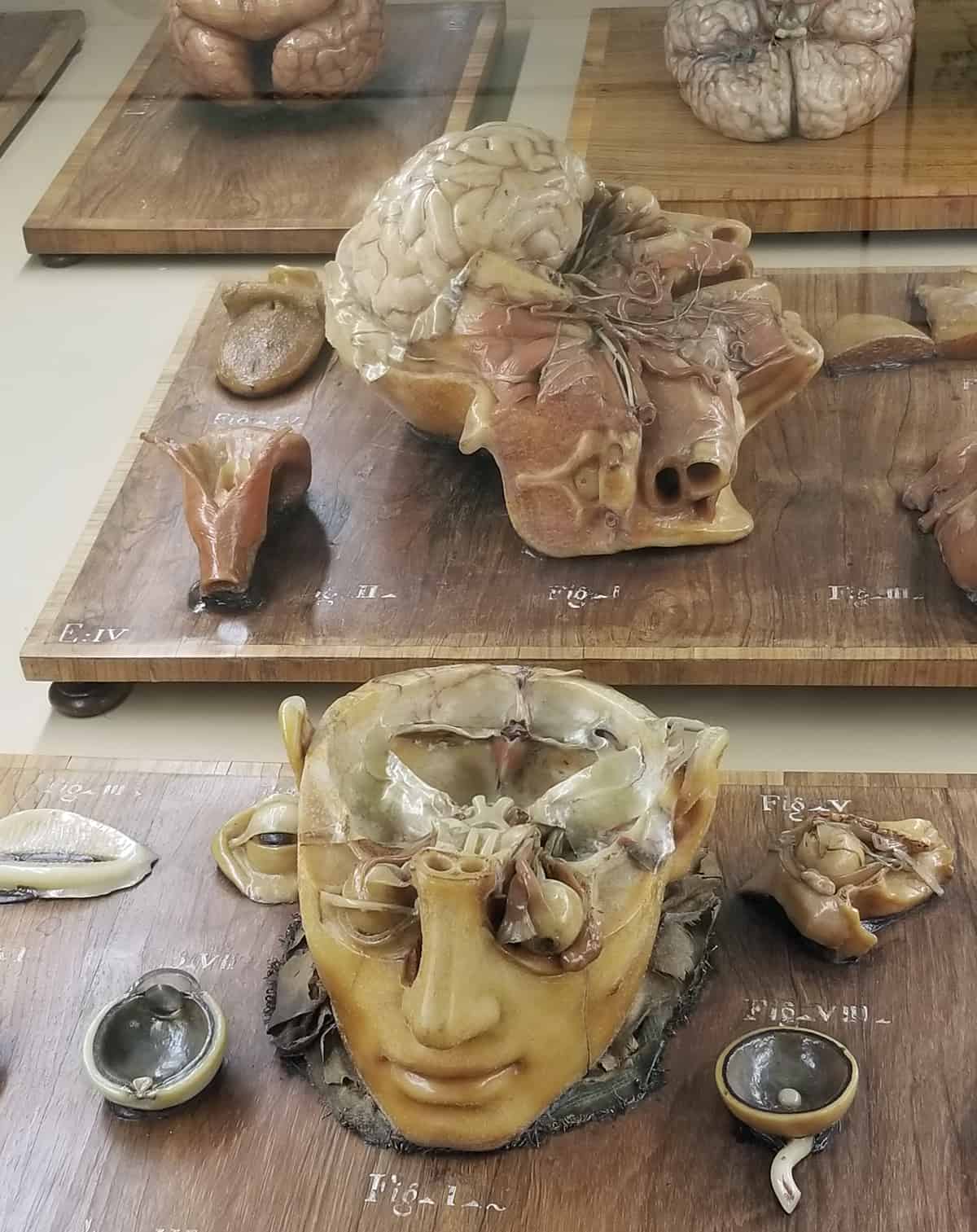

After the Lankton installation, the glass and wood display cabinets in the University Museo di Palazzo Poggi in Bologna, Italy, seemed at first glance tame and traditional. Before long, however, it was apparent that they were just as jarring. Since 2002, in addition to their 18th-century Normal Human Anatomy collection, the museum has on display a remarkable 19th-century collection of Normal and Pathological Human Anatomy—wax models, bones, and mummified and formalin-preserved specimens that look like objects from a horror movie. Determined to show the human body and human pathology in a realistic manner, many 18th and 19th-century scientists relied on artists to make three-dimensional models and paintings. It was art in the service of science, with a decidedly pragmatic purpose.

Despite the museum’s scientific purpose, and the unfamiliarity and complexity of its technical wall labels, the wax works on view are clearly art: finely crafted sculptural pieces, much like those which are currently being rediscovered and integrated into art museum exhibits such as Like Life.

Made by the Bolognese artist Ercole Lelli (1702-1776), who founded the Bologna wax anatomy school in 1742, the works are distinguished by the subtle coloring of their skin, the naturalness of their three-dimensionality, and by their extraordinarily realistic size and scale. No contemporary plastic surgeon could have done better. Lelli, who was often assisted by the sculptor Domenico Pio, inspired two disciples, Giovanni Manzolini and his wife Anna Morandi, the first Italian female anatomist and ceroplastic artist. All three were gifted artists whose wax models replicated human anatomy, detailing ears, noses, tongues, hearts, lungs, female genitals, and fetuses, as well as revealing the complexities of the nervous system and muscles. Their wax works are full-flesh pieces, pierced by nerves, bones, and tendons. Masterfully colored, they are compelling works of art.

Another renowned wax artist, Clemente Susini, who worked in Florence, produced some 2000 anatomical works. The most famous of them, La Venerina (1780-1782), renders a young woman’s body with removable organs. The original model is at the Palazzo Poggi; the thorax and abdomen can be opened, allowing the body to be disassembled for an anatomic dissection. Layers can be removed to reveal the veins, the arteries, and the internal organs. La Venerina carries a fetus in her womb, although there is no other physical sign of pregnancy. A version of the work, An Anatomical Venus (1780-1785), from the same workshop, can also be found in the Like Life exhibit. The anatomical models were vital to medical education in their time, adding a visual component to the theoretical lectures. The modelers, of course, benefited as well. “For these artists,” Prof. Hansen said, “making wax models was one way to earn a living, much like portrait painting was to painters.

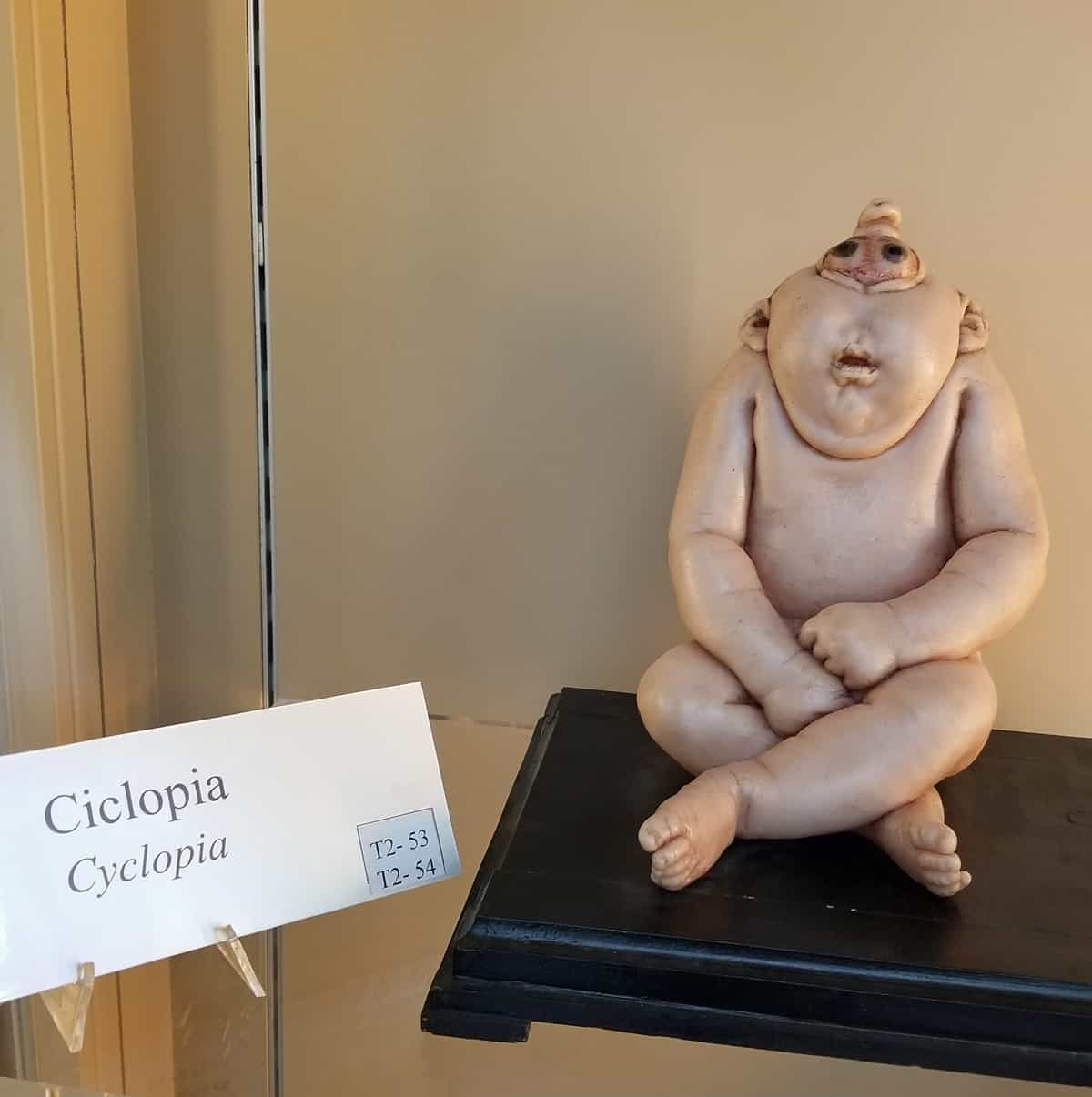

A short walk away is the Collezione Delle Cere Anatomiche “Luigi Cattaneo,” where fifth-year University of Bologna medical student Hussein Othman pauses before a case to answer my question. “No,” he admitted candidly, his professors never brought him to the museum to study the models. “We have other methods now; books and online models which resemble the collections in the museum.” Still, archeology major Martina Orsoni, who accompanied him on the tour, stressed that the wax models remain important. “Nowadays, it is difficult to find this pathology,” she said, pointing to a wax and gypsum (plaster) model of cyclopia (or cyclocephaly), a birth defect where the head has only one cavity for both eyes. “These models are very particular. They are more than wax. They have a great impact. They are scary but very interesting.”

There’s a wax model of conjoined twins who share their genitalia and legs, their life-size wax heads containing graphically detailed brains and eyeballs. There’s a woman whose face and neck are totally covered with pus-filled blisters identified as “Human smallpox.” Nearby, there is a ghost-like head of a man with almost no pigment in his eyes, labeled “Albinism,” and another head with thickened and dark blotchy skin marked as “Pellagra.” Following in the tradition begun by Ercole Lelli, Giuseppe Astorri worked as the official modeler at the University of Bologna, collaborating with three Professors of Anatomy. Astorri molded the wax directly onto real bone, according to the wall text, making models that were “notable for their precision of detail and uncontested artistic value.” Later, he shifted to the technique of the Florentine school, using an imitation marble or stone mold of plaster with glue and dyes, taken directly from a corpse. With the help of Professor Luigi Calori, Astorri produced “realistic and elegant models of congenital malformations and skin pathologies.”

Pursuing the braided history of medicina and arte in Italy inevitably involves a visit to two of the country’s historic anatomical theaters. At the University of Bologna, the Anatomical Theatre of the Archiginnasio is a rectangular room carved from spruce, following the design of the architect Antonio Paolucci, also known as Levanti. It dates to 1636-1638, although the whole building was not completed until 1737. A white marble table in the center of the theatre, on which assistants dissected human and animal bodies, draws the eye. Two groups of statues decorate the room: at the base, twelve celebrated doctors, including Hippocrates and Galen, and, above, 20 of the most famous anatomists of the Studio Bolognese. Towering above the dissecting table is the teacher’s chair, with two spellati—anatomical models with their muscles exposed, much like Lami’s The Digger, made over a century later. Sculpted in 1734 and based on a drawing by Ercole Lelli, the spellati hold up a canopy upon which is a female figure representing anatomy. Two angels can be seen handing the woman a gift of a thighbone. “The anatomical theatre was built as a part of a higher education institute by the Pope,” Prof. Hansen explained.

Definitely more dramatic in design is the conical Anatomical Theatre at the University of Padua, located in the Palazzo del Bo. Conceived by Girolamo Fabrici d’Acquapendente, the theatre was completed in 1595 and remained in use until 1870. Created to teach anatomy through the dissection of corpses, it is the first example in the world of a permanent anatomical theatre. Concentric oval balconies of increasing size rise from the level of the operating table to allow two hundred and fifty students to see the dissection from their perches. This architectural gem was clearly conceived as a working classroom. The Latin inscription above the entrance to the theatre reads: “Hic est locus ubi mors gaudet succurrere vitam”—This is the place where death rejoices in succoring life.

Arte and medicina truly share the spotlight at the Ospedale Maggiore in Milan, a Renaissance building, now an archive and a museum, housed within a modern hospital complex that was founded in the 15th century as a service for the poor. “It was totally free for patients. If you knocked on the door, you were accepted,” said Dr. Paolo Galimberti, Director of Cultural Heritage at the Maggiore and a paleographer, an expert on ancient and historical handwriting.

With a slender staff of two, augmented by student volunteers, Dr. Galimberti oversees an impressive collection that includes more than 900 portraits of important donors to the Ospedale. Spanning from 1584 to the present (today, a donation of 250,000 Euros covers the inclusion of a small painting; a gift of over 1 million Euros a big portrait), the collection is remarkable not only as a record of donors’ generosity but also “as an artistic archive that reveals much about the history of society and the history of fashion over the centuries,” Galimberti said. At times, the hospital acted as a curator by selecting the artist who would paint a donor’s portrait; at other times, donors already had suitable portraits in their libraries at home which they donated.

Two paintings hang side-by-side in the entrance hall, one of Arrigo Recordati (2004), an important donor, by Alessandro Papetti, and the other of Giuseppe de Palo (1985), a man who sold lemons on the streets of the city, by Francesco Tabusso. “De Palo represents all of the normal people,” Galimberti said, “who also contribute to the hospital.” Across from the paintings is a marble bust of Dr. Giambattista Monteggia by Camillo Pacetti (c. 1815). “Typically, doctors are represented in Italy by busts rather than painted portraits as was common in Northern Europe,” explained Prof. Hansen.

In the basement, the collection of portrait paintings hangs on sliding racks. There’s Felice Cameroni, a journalist and a donor, too, by Luigi Rossi. There’s donor Savina Alfieri Nasoni, by Emilio Longoni, and Giuseppe Scotti, a donor and a doctor, too, by Sala Eliseo. There’s a fascinating portrait of Maria Valcarzel y Cordova del Sesto (1708) signing her last will, which includes a donation to the hospital. “We like to use photos of this painting,” Galimberti quipped. Two of the earliest paintings depict influential archbishops; the first is of San Carlo Borromeo (1584) by Ottavio Bizzozzero. “Art historians often come here to study these paintings,” Galimberti said.

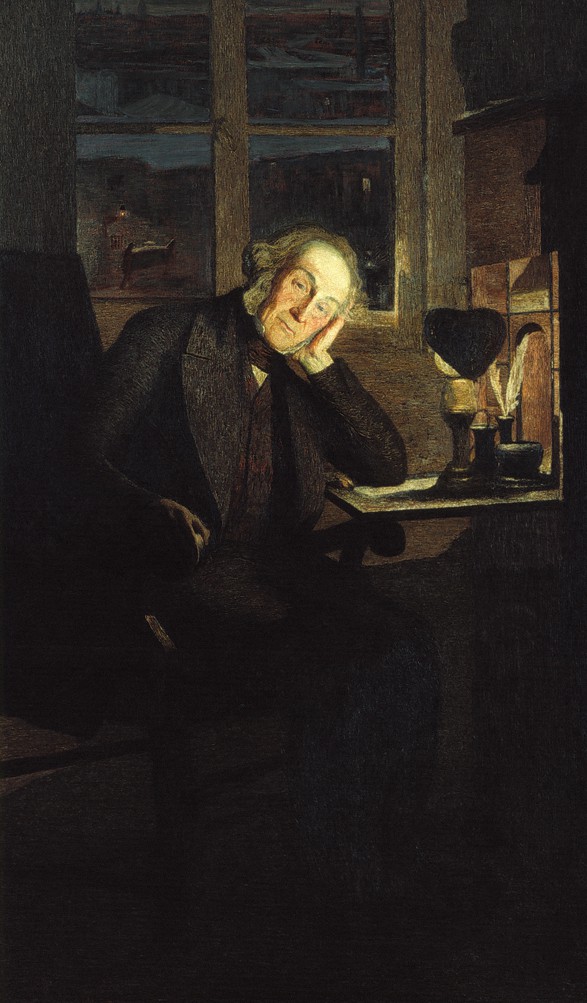

There is a 1917 portrait of Dr. Giovanni Balleriro by artist Carlo Carra. In the portrait, Dr. Balleriro sits at his desk, his pose serious, light from a small lamp illuminating his face. Also in the collection is a portrait of Carlo Rotta (1855) by Giovanni Segantini that was included in a 2005 show at the Guggenheim in New York. “He is the father of the donor and it is our only portrait by Segantini,” Palimberti said.

Currently, Dr. Galimberti has no funding to add to the collection, but he is busy writing grant proposals. If he had 12 million Euros, he would restore the entire building and install a permanent exhibit illuminating the interwoven history of medicine and art.

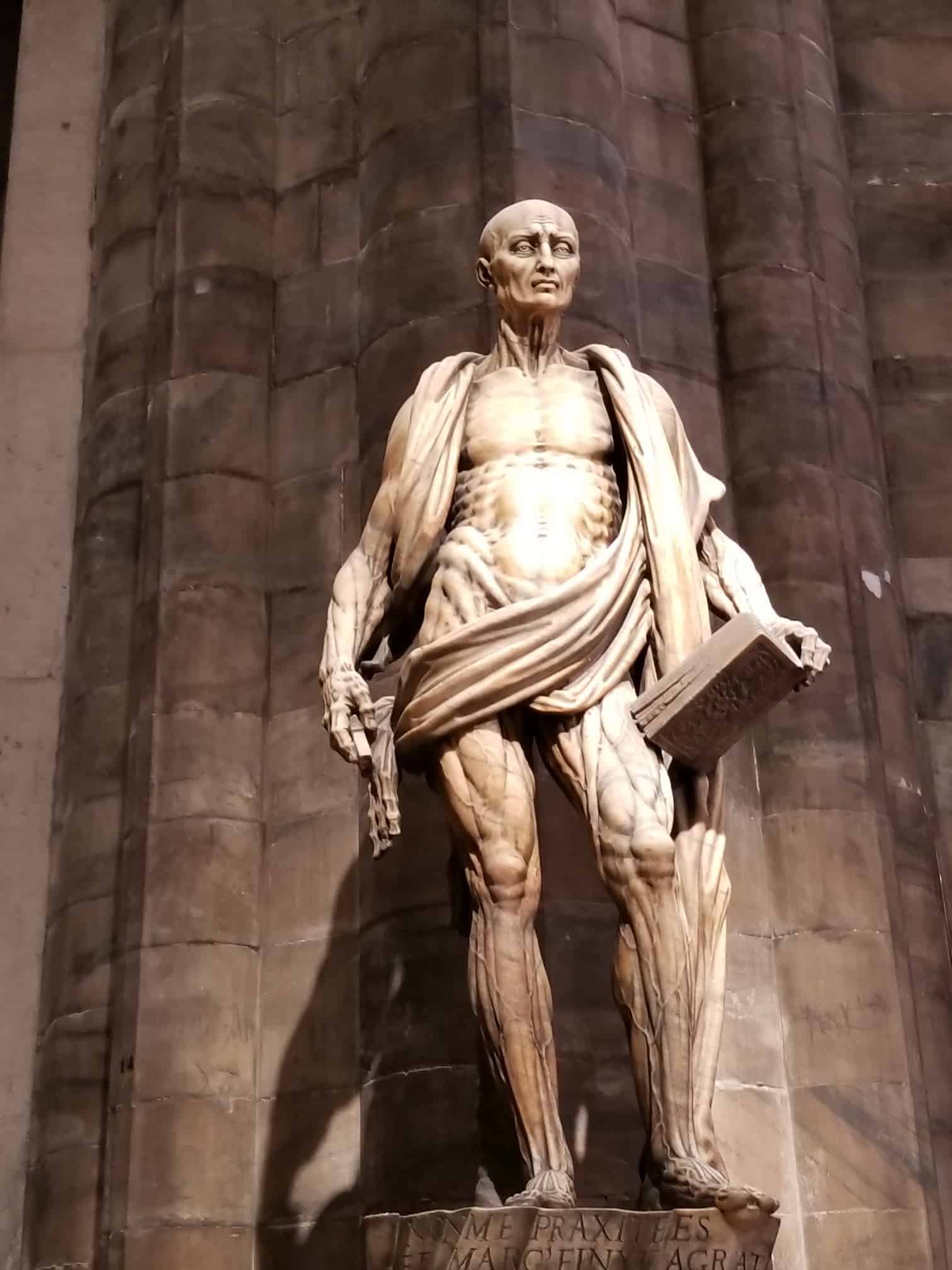

On a tour of the Duomo in Milan, the guide directs the group to his favorite sculpture, the figure of St. Bartholomew Flayed (1562), the best known work of Marco d’Agrate (1504-c.1574). Most of the tourists assembled in the church know the apostle’s story, how Saint Bartholomew was skinned and, in some versions, decapitated. How artists throughout the centuries in painting and sculpture have tried to capture his essence and his sacrifice.

The statue is bold, even disturbing, revealing its veins, arteries, and tendons. The saint’s skin drapes around his body like a loose garment. Below the work, there is a carved inscription by the artist claiming full recognition for his morbid creation: “I was not made by Praxiteles [the renowned Attic sculptor who was the first to sculpt the nude female figure in a life-size statue] but by Marco d’Agrate.”

The work is remarkable for the intense realism of its muscles and sinews. It is a work of art presented to worshippers in a cathedral. But, if the statue had not been too big to move, it would have fit perfectly into the Like Life show at the Met Breuer.