By Scott Korb

What follows is the slightly edited text of the author’s commencement remarks at the Pacific University MFA in Writing Program on June 27, 2015.

Let me begin by offering my thanks and congratulations to all the graduates today. I hope to do your accomplishment justice with a few words about the writing life.

I also think I’d be remiss in not acknowledging that while we’ve all been together on campus these past few days, working hard, heads down, the world out there’s been changed by tragedy, on the one hand, and justice, again, finally, on the other. I, for one, look forward to entering back into this changed world—bringing with me what I’ve learned this week from all of you—better equipped to reckon with what we’ll find. More tragedy. And more justice. Again and again.

I am, as many of you know, a personal essay writer and kind-of-journalist who often dips into memoir, so I hope you’ll indulge me a bit.

In 1998, when I moved from Madison, Wisconsin, to New York City, where I began a Master’s Degree in theology, I arrived with a BA in Literature and what they called at the University of Wisconsin a “certificate” in creative writing. I turned twenty-two my first week in the city. Most of my colleagues at Union Seminary were of a generation above my own—second-career ministers-in-training, one former Wall Street guy with alopecia getting a degree in Christian ethics, a number of men and women pursuing advanced degrees after raising kids (kids who were then my age)—and, feeling unclose to them, on the weekends I got into the habit of taking the train downtown to rock shows at clubs that no longer exist. I would go by myself. I maintained a long-distance romance over that semester, and during the week, with the time I had after completing my schoolwork, I impressed myself with letters I wrote to my girlfriend, who was studying abroad in Chile. When I visited her at Thanksgiving, I noticed she’d gotten close to a Santiagan she was studying with, and a few months later, after winter break, I returned to New York a single man.

As an older person now—with at least some experience in this writing life—I’m often asked a question that I’ve decided to try to answer today. The most obvious thing to note about this question is that it’s one we all could be asked and all have an equally authoritative answer to. We can think of it as the question of the memoir. It takes various forms: How did you get where you are? How have you done what you’ve done? For most of us here, the operative question probably goes something like this: How did you become a writer? The answer to that begins, for me, in that post-New Year’s moment, 1999.

Looking back, it began not with any “certificate,” but rather the sense I had at 22—then an aspiring writer, imagining a novel that I would write but never publish—that graduate school can, but should not be, a lonely place.

Feeling pretty alone in the world when I returned to the city that winter—and probably also a little heartbroken—I knew I needed friends. I’d done some acting in high school, and when I saw a flyer advertising auditions for a Shakespeare production at Columbia University, I tried out and was given a part. A little tipsy one night at a party following a performance, I flirted with a woman by telling her I was starring in Hamlet, playing Horatio.

We went out and read together, listened to each other read and act and otherwise perform. This is how I became a writer. By deciding not to be alone.

At first suspicious of each other, Laertes and I quickly became good friends. After the play concluded its run, we soon began writing together—long, elaborate letters that played for laughs a rivalry we’d invented for the purpose of getting letters published on McSweeney’s Internet Tendency, a website that’s still going—a website that you can write for—and which was then the place where we cut our teeth. A great big bunch of us did.

Inspired by this community of writers, Laertes and I decided to make a magazine together—we called it The American Journal of Print—modeled, perhaps embarrassingly so, on McSweeney’s, and we raised money to print our journals with our own versions of benefit galas, with readings and live music. This was fun.

For the magazine, Laertes and I solicited essays and articles—and both responded to similar solicitations from others—by the whole big bunch of us all trying trying trying (as McSweeney’s was then fond of saying) to become writers. We edited each other, wrote for each other; we published each other and ourselves. Mainly we went out and read together, listened to each other read and act and otherwise perform. This is how I became a writer. By deciding not to be alone.

The American Journal of Print published in our first issue part of the novel I was writing. We published in our second issue a reflection by Laertes about deciding to go to the office the morning of 9/11: “Catch the eye of one coworker with whom you are friends,” he wrote. “This coworker’s face will start to shine with tears. This coworker will be in need of comfort. This coworker will be in need of you.” Laertes is now at Cosmo, still making a magazine. Who else would we publish? They’d become editors—at Slate and Vice and McSweeney’s, the University of Chicago and DC Comics; a staff writer for Entertainment Weekly; novelists and storywriters and poets of all kinds, with book after book after book; contributors to countless magazines and newspapers, including Harper’s, The Paris Review, BOMB, Bookforum, Wired, the Wall Street Journal, the New York Times, NYLON; a regular on This American Life who would write the magazine story behind the Academy Award-winning ARGO. I’m not saying we launched a lot of careers with our little magazine. But we were there in the early days of a lot of careers. We made a lot of friends.

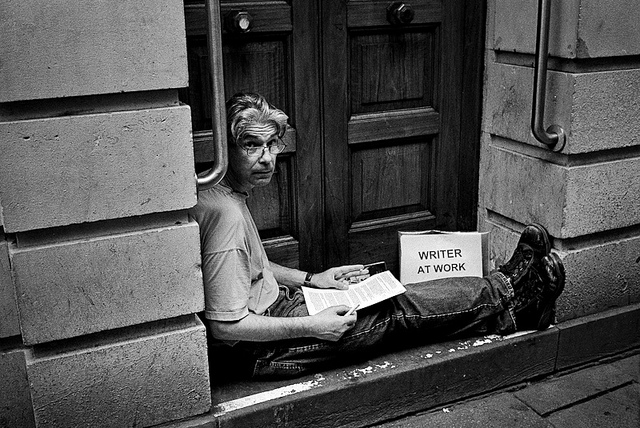

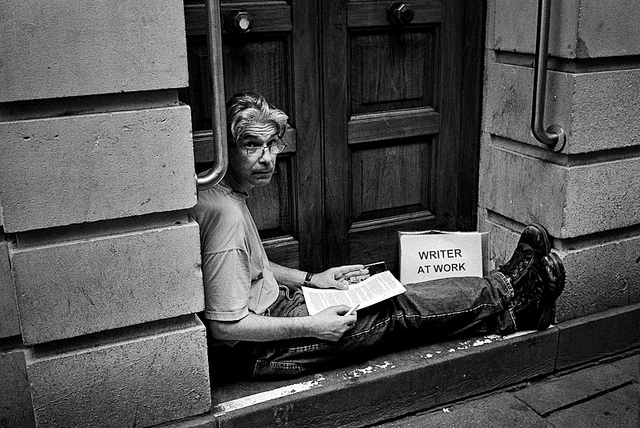

Writing is work. It takes practice. And that practice is typically solitary.

And we published another collaborator of mine—two nonfiction pieces he wrote about birds and clocks. With him I’d write my first book. He’s gone on to do a few more.

It was at our book-release party, in November 2007, hosted by another friend with books in the works at a now-defunct bar with a spectacular reading series, that I met my wife. That relationship is one Laertes, my kid’s godfather, often takes credit for—which, looking back, is not unreasonable. We came up together, I like to say; we all did. Without him—without all of them—it’s hard to see how I’m here teaching, or here talking with you today, congratulating you for your hard work, for all the support you’re giving one another.

Okay—some caveats to all this. The first should be obvious. The backbone of the writer’s life is the writing itself. And all of the people I’m talking about, all the people I’ve come up with—which now, in a way, includes all of you—have committed themselves to the truism that writing is the work of putting down one word after another. And starting from there—either through practice or study, and often both—we’ve all likewise given ourselves over to developing our craft: taking lessons about being more productive, about making the most of an object or gesture and finding inspiration in genres we don’t call our own, about signaling authority and gaining and maintaining a reader’s trust, about making meaning of bodies in motion, about revising, about voice and imitation, about music.

Writing is work. It takes practice. And that practice is typically solitary.

Caveat number two has to do with the times and places I normally tell the story I’ve so far told. For instance, I’ve never said any of this from a stage. Never in front of a university president or a dean. Never wearing a tie, much less a gown. I’ve never followed a bagpipe.

In finding I wasn’t alone—in what I hoped to do; in acknowledging whom I hoped to reach—writing itself became possible.

More often than not, the story comes after I’ve responded to an email from a student who’s taken a writing workshop with me—she wants to be a writer, but is such a life possible?—and we’ve been sitting across a small table in a crowded coffee shop for half an hour—I don’t have an office—and I’ve talked about being in my twenties, going to readings, finding—making—a community. Throwing parties. My first book, a novel, gets me an agent but doesn’t ever come out. No, I say, it never will; we all have the book in a drawer. Write for websites, I say. Sometimes for free. Read, I say. Lots. Write about what you’re reading. We both sip from our coffees. And I often end my rambling with: “Is this what you wanted to hear? Is this at all helpful?”

Spelled out—caveat number two: Writing is work. Writing, like most work, is mostly unglamorous. Book parties are fun, and they are special moments (even when they don’t lead to romance, a kid, eventually a marriage); don’t get me wrong. Getting opportunities to speak publically—on radio, on TV, on the internet or in a magazine—about a piece of work months or years in the making can be thrilling; and it’s part of this work I enjoy. When it comes for you, you may not enjoy it at all.

Getting other public attention—reviews, say—is always going to be a mixed bag, both good and bad for the ego, sure; but at its best, criticism represents a deepening of the ideas present in a work of art, and for those of us who’ve made it, a measure of what we’ve been able to accomplish in writing and an expression of someone else’s thought that may itself be a revelation.

All that said, I think that for most of us with the vanity it takes to put our words down, one after another, for others to read, the humbling quality of the writer’s life—its basic and typical anti-glamor—provides the proper check on the ego necessary to write anything of value at all. I said before that I became a writer by deciding not to be alone. It’s probably more true to say that in finding I wasn’t alone—in what I hoped to do; in acknowledging whom I hoped to reach—writing itself became possible.

Is such a life possible? Yes, of course. Look around. It’s possible. But not by yourself. You can’t do it alone.

And when I sit at cafes with one writer at a time—often surrounded by the plugged-in, headphoned writers of our day—offering this answer sometimes feels a little unfair. She’s not sure this is what she wanted to hear. She’s not sure if it’s at all helpful. Shouldn’t it be enough that she can put one word in front of another in a way that makes sense? That’s beautiful? Shouldn’t a pen and paper, a computer and printer—some headphones to block out the world—be enough to make the writer? Why does she need anything, or anyone, else? Making friends, trusting people, is hard.

And yet, what I’ve seen in my two years here is a readiness—an enthusiasm—for doing the hard thing. Yes, the hard thing of writing, editing, revising; yes, the hard thing of letting go, of publishing.

Yet—more impressive still, I think, for the long run, has been what I’ve seen of trust—in friendship, in collaboration. In a poem inspired by or dedicated to someone you’ve met here. From workshops to the reading series, notes passed and shared during craft talks—lunch conversations, hallway conversations, party conversations that pick up where a classroom conversation left off. And onward into our semesters apart, when it’s even harder to be in touch. You do the hard thing. You do the beautiful thing.

And so—this setting is perhaps the better one, the fairer one, to deliver the news that you’ll need each other. Look around. Of course it’s possible. Remember that. Just stay close.