By Roz Bernstein

A few weeks ago, I saw a screening of Tom Hayes’s Smiling Through the Apocalypse, his documentary about his father Harold Hayes, the legendary editor of Esquire Magazine who died in 1989. The screening was held in the Center for Communication auditorium where some one hundred and fifty of the guests were current and former Esquire employees and friends invited by Tom Hayes. I scanned the audience looking for familiar faces—folks I had known during those crazy years, 1964–1967 when I worked for Byron Dobell, then Esquire’s managing editor in the magazine’s offices on Madison Avenue. The first few rows had reserved signs on the seats but I only recognized a few of the honorees: Gay Talese, Tom Wolfe and his wife, Sheila Berger Wolfe, Byron Dobell, and George Lois, who as I recall was paid $500 for each cover design that he did for the magazine.

Those days, the NYC subways were filled with speedwriting ads that read, “If u cn rd ths mg, u cn bcm a sec & gt a gd job w hi pa.”

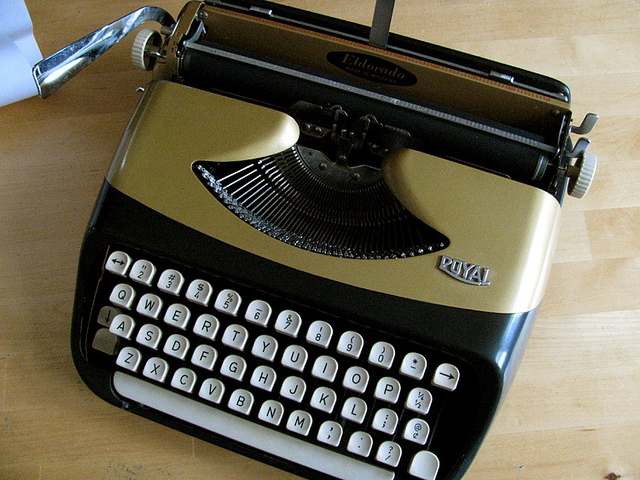

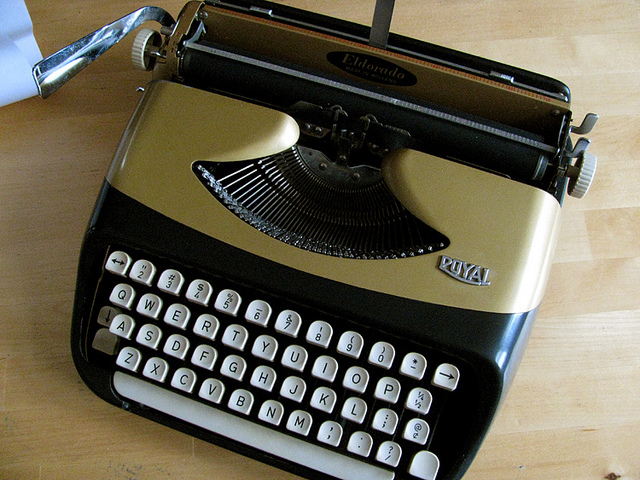

I was in between careers then, having decided not to go on to medical school but not yet having decided to begin pursuing my Ph.D. in English. One day, scanning the help wanted ads in the New York Times, I found a listing for a secretary at Esquire: “Good command of English and knowledge of shorthand a must.” Written English was no problem. But, like most liberal arts students then and now, I didn’t know any shorthand.

Those days, the NYC subways were filled with speedwriting ads that read, “If u cn rd ths mg, u cn bcm a sec & gt a gd job w hi pa.” Although I didn’t exactly want to become a secretary—I had majored in Political Science at Brandeis, studied with some of the great European intellectuals like Herbert Marcuse and Abraham Maslow, had graduated magna cum laude—I coveted a job at Esquire. I knew that it was the magazine that published Ernest Hemingway and F. Scott Fitzgerald. I knew that it was the “hot” spot in magazine publishing with publisher Arnold Gingrich anointing Harold Hayes as Editor-in-Chief just one year earlier. I made my way to the Strand and found myself a used copy of the speedwriting book.

For the next two days, I memorized it. It was definitely easier than organic chemistry. After a short interview with Byron Dobell, who asked me repeatedly why I wanted to be a secretary, he dictated a letter. I took down his words in speedwriting. When I went to type up my scrawl, I found that I could not make out several entries and I improvised, rewriting the letter. I remember fondly Byron laughing when he said: “Those weren’t exactly my words but you’re a good writer and you’re hired.”

Had we gone too far? Of course! Could we go just a bit further?

So began my adventure at Esquire, where life and art often clashed, where politics and personality prevailed, and where genius was much too close to madness. The suite of offices was physically small with Harold’s corner office, the innermost sanctum, protected by the desk of his secretary, Connie Wood. Next door was Byron’s windowless office, with my desk outside—placed perfectly to greet almost everyone who was sent inside by the receptionist at the elevators. Over the years, Diane Arbus often stood before me in her safari jacket, her heavy cameras slung over her neck. I never remember her smiling. There was Tom Wolfe, dashing in his white suit, and Norman Mailer, stopping by my desk on his way in to see Harold. I remember once having to deliver a note to Norman and Harold when they were having lunch in the Oak Room of the Plaza. The waiters hassled me because women were not allowed inside. They would be happy to deliver the note, they said. But I persevered, ultimately handing the note to Harold as Norman nodded approvingly. “I’ll take a swing at them,” Norman said, although for once he didn’t.

The editors and junior editors, the editorial assistants, even the secretaries, we all lived in awe and fear of Harold Hayes. I arrived there already married, having wed Elliott Bernstein, a Business Week editor, in June 1964. That status placed me somewhat off the grid. The singles hung out, dated, drank, and sometimes shared beds.

Harold loomed over us all, the great father we had to please, the Southern gentleman who only superficially seemed like a good ole boy. For days before the Friday editorial meetings in his office, editors would scramble, often secretively, to come up with new ideas. The pressure was enormous. Assistant Editor Alice Glaser once told me that she dreaded the sessions and that she could not sleep the night before. She feared that her ideas might just not be sharp enough to impress Harold.

We drank at the bar around the corner where the bartender made sure that the drinks were always doubles.

We were filled with the angst of the 1960s—civil rights, the Vietnam War, the beginning of the women’s movement. On the walls of the art department were the thumbnail layouts of the next few issues. In charge was Sam Antupit, a man who, like Harold, wanted—needed—to break the rules. A few offices down, there was Cathy McBride, Esquire’s copy editor. Nothing, nothing passed her by. There was Fritz Bamberger, our legal counsel, who was always being sent something or other to rule on. Had we gone too far? Of course! Could we go just a bit further?

We drank at the bar around the corner where the bartender made sure that the drinks were always doubles. The first time I showed up, at Connie Wood’s invitation, I drank two martinis, not realizing that they were actually four. Afterwards, I stood on Park Avenue for nearly fifteen minutes trying to figure out which way was downtown.

Downtown was where I lived but uptown was where I worked and played and created. At that marvelous magazine, the one that ran a cover of John F. Kennedy, a hand wiping tears from his eye, to illustrate Tom Wicker’s moving profile, “Kennedy Without Tears.” It appeared in the June 1964 issue, only seven months after the assassination. I was there the day that the magazine arrived and we all cried.

Memory is a funny thing. Sometimes, sharp edges are worn dull; sometimes, small moments take on enormous significance. I watched Hayes’s documentary, a son’s tribute to his father—inclusive, comprehensive, and reverential—cover after cover flitting by, but, somehow, I missed in the film the passion that I remembered. The fierce frenzy of my Esquire years. The crazy creativity. The not knowing what was coming next.

“Smiling Through the Apocalypse” is currently being screened at festivals—Tom Hayes is looking for “someone to take the film to a few major cities theatrically, perhaps art houses,” or to release on cable or DVD.

Roslyn Bernstein reports on arts and culture for such online publications as Buzzine, Huffington Post, and Guernica. Bernstein is a professor of journalism at Baruch College, CUNY and the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism. She is the author of Boardwalk Stories and the co-author of Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo.