"Bob Donlon (Rob Donnelly, Kerouac's Desolation Angels), Neal Cassady...." / Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Gift of Gary S. Davis

By Roslyn Bernstein

In the summer of 1964, while enrolled in pre-med courses at New York University, I moved into my new digs, a square room under the bell tower in Judson Memorial Church. It had windows that looked north and south, and I willingly climbed the flights of stairs to my Greenwich Village perch.

That summer, from above, I watched the revelry in Washington Square Park, and from below, I listened to the poets, stoned and sober, chant in the nearby coffee shops on MacDougal and Bleecker Streets. Some time in July, I heard Allen Ginsberg read for the first time, in a smoke-filled room packed with worshippers.

It was a voice and a vision that I would never forget, the howl of a poet who “saw the best minds of [his] generation destroyed by madness, starving hysterical naked,” the rant of a man who spoke of “angelheaded hipsters burning for the ancient heavenly connection to the starry dynamo in the machinery of night.”

So it was with considerable nostalgia that I went recently to see Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg, an exhibit from the National Gallery of Art (2010) that has just opened at Grey Art Gallery, New York University—with additional images, supplemented by original manuscripts, typewritten poems, correspondence, drawings, and sketches drawn from Beat materials at NYU’s Fales Library.

Many of the snapshots in the exhibit come from the collection of Gary S. Davis, who became interested in Ginsberg’s photos in 2000 and built his collection at the Howard Greenberg Gallery, which represents the Ginsberg estate. As of December 2012, Davis has given 198 Ginsberg prints to the National Gallery.

These are not just captions, identifying the people in the photograph from left to right but rather poignant, passionate, and irreverent observations, some written thirty years after the original photos were taken.

Organized by the National Gallery of Art in Washington and curated by senior curator of photographs Sarah Greenough, the Grey exhibit features ninety-four black-and-white works, from two distinct periods when Ginsberg was engaged with photography, the 1950s and 1960s and the 1980s and 1990s. The photographs, Greenough said, “form a vivid, and compelling portrait of a generation of American poets, writers, artists, musicians, and counterculture activists, providing us with intimate, occasionally amusing insights into their lives and activities…. Just like his poetry, they are the result of his intense observation of the world, his deep appreciation of the beauty of the vernacular, his desire to celebrate the sacredness of the present, and his faith in intuitive expression.”

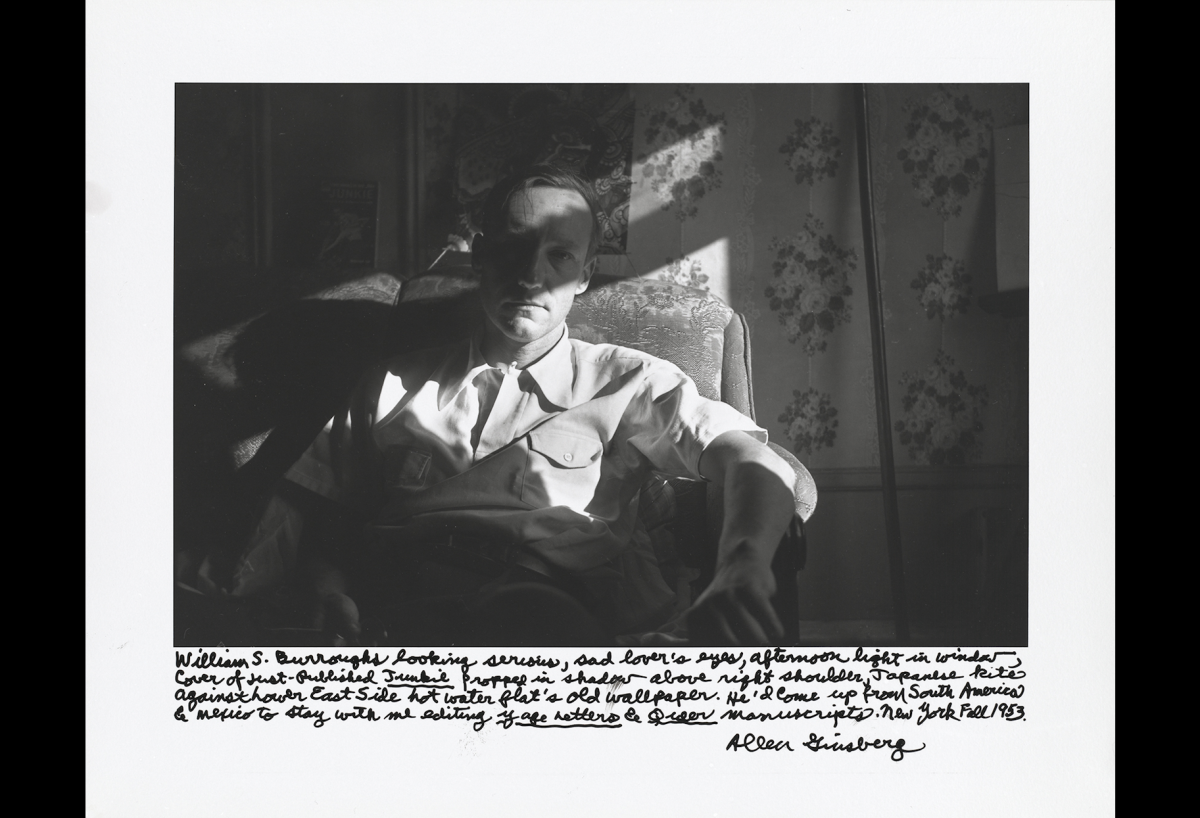

Many of the earlier images were reprinted in larger format from the 1980s onward to accommodate adding handwritten inscriptions. These are not just captions, identifying the people in the photograph from left to right but rather poignant, passionate, and irreverent observations, some written thirty years after the original photos were taken.

Ginsberg’s words on Bill Burroughs in back bedroom waiting for company…, a larger format print (1984-1997) of a 1953 silver gelatin photo of William Burroughs lying in bed in his underwear, provide the back-story for the original image, piercing that moment in time when Ginsberg and Burroughs were lovers:

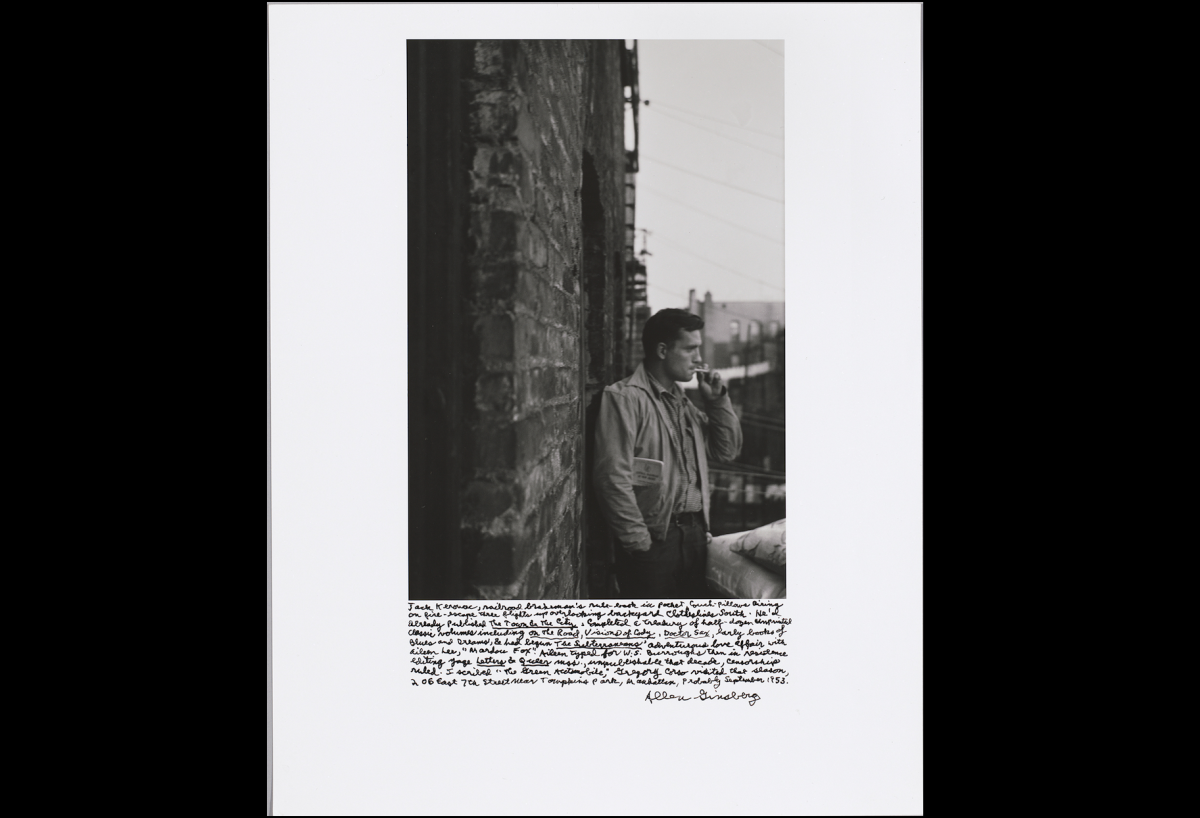

From 1953 to 1963 Ginsberg, armed with a small, secondhand Kodak Retina camera that he bought for thirteen dollars and often tucked into his jacket pocket, shot snapshots that captured, as Sarah Greenough writes, “the playful quality of his close-knit group of friends.” We see Kerouac beneath the Brooklyn Bridge singing blues and chanting the words of Edgar Allen Poe and Hart Crane and making a “Dostoyevsky mad-face” near Tompkins Square Park.

The photographs (and negatives) from the 1950s remained unpublished for thirty years. They were, Ginsberg wrote, “meant more for a public in heaven than one here on earth—and that’s why they’re charming.” After Ginsberg’s papers were given to Columbia University, an archivist there discovered the photos and negatives and contacted Ginsberg. The idea was for Ginsberg to identify the people in the photos, nothing more. But with encouragement from the photographers Robert Frank and Berenice Abbott, Ginsberg, the innovator, the visionary, did more. He had many of his earlier photographs reprinted, adding extensive inscriptions, carefully punctuated and full of parenthetical details.

After a lapse of twenty years, Ginsberg took up photography again in the 1980s, using the same service as Frank to make prints. He took Frank’s advice on cropping photos, on including hands in his portraits, and on coming closer to his subjects. Frank also suggested that Ginsberg buy a Leica camera which he did, using it to shoot some of his later photographs. Abbott advised him: “Don’t be a shutterbug, young man.” She wanted him to slow down and use a large-format camera for panoramic views. But most important of all, Abbott’s extensive writing about her own photographs—describing how and why she shot specific images—inspired Ginsberg.

Robert Frank had begun writing on his photographs in the 1970s and Frank suggested that Ginsberg look at the work of other innovative photographers who were experimenting with the mingling of words and images: Duane Michals, Jim Goldberg (Rich and Poor), and Elsa Dorfman (Elsa’s Housebook: A Woman’s Photojournal).

The inexpensive little camera caught them celebrating life together—not at the big historic moments like the first reading of Howl but rather casual moments when they were eating, sleeping, traveling, and just plain hanging out.

Their experiments appealed to Ginsberg who began adding extensive, handwritten captions to his prints, creating his own version of a “bookmovie,” described by his friend Jack Kerouac in his “Belief & Technique for Modern Prose” as “the visual American form.” Kerouac advised writers: “Don’t think of words when you stop but to see picture better” and “Write for the world to read and see yr exact pictures of it.” Perfect advice for Ginsberg, the poet and Ginsberg, the photographer.

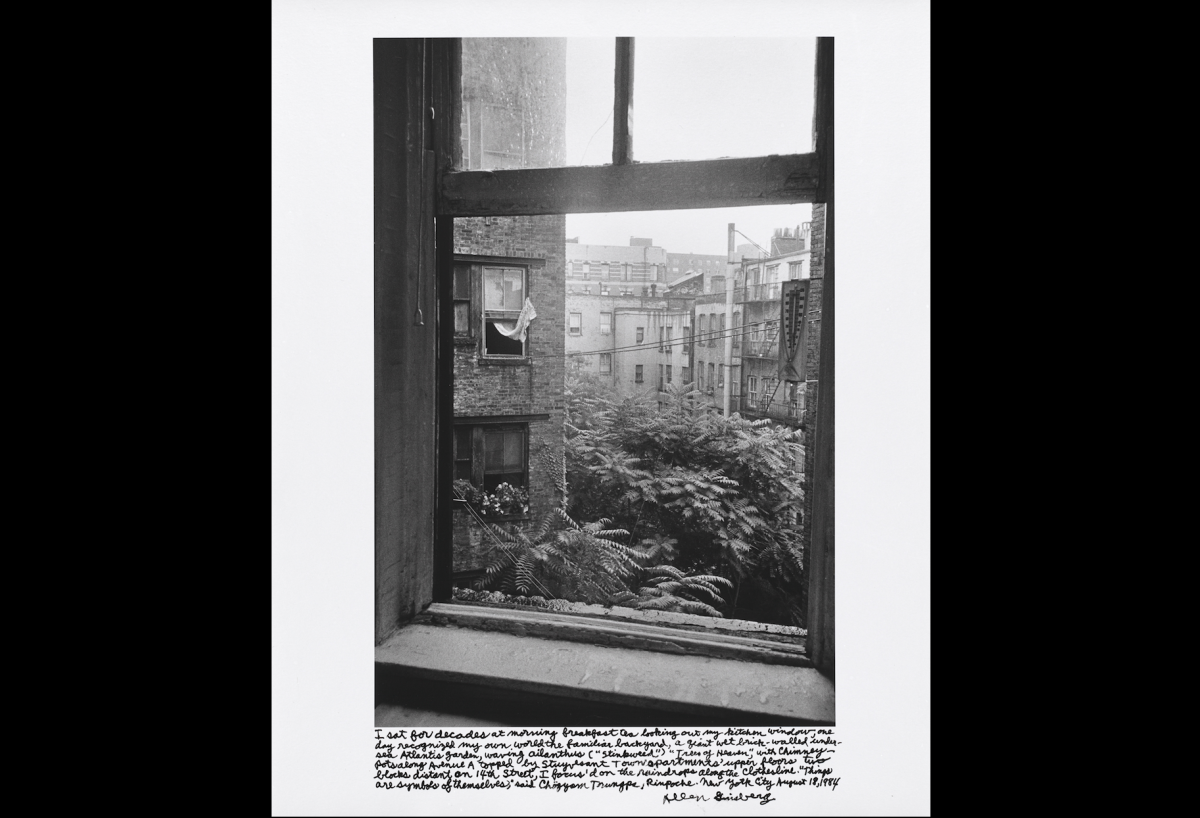

Ginsberg wrote that “the poignancy of a photograph comes from looking back to a fleeting moment in a floating world.” These words are especially true of the snapshots and drugstore prints in the exhibit: small images, many three by four inches, most without captions. These photos are not carefully composed, and they are definitely not in sharp focus. They do not illuminate historic moments in Beat history. Rather, they are more like the intimate snapshots in a family album, warm, fuzzy, funny, sad, and sometimes puzzling. All that they are missing, to recreate the vintage moment are the black photo corners which were so popular in the albums of the 1950s.

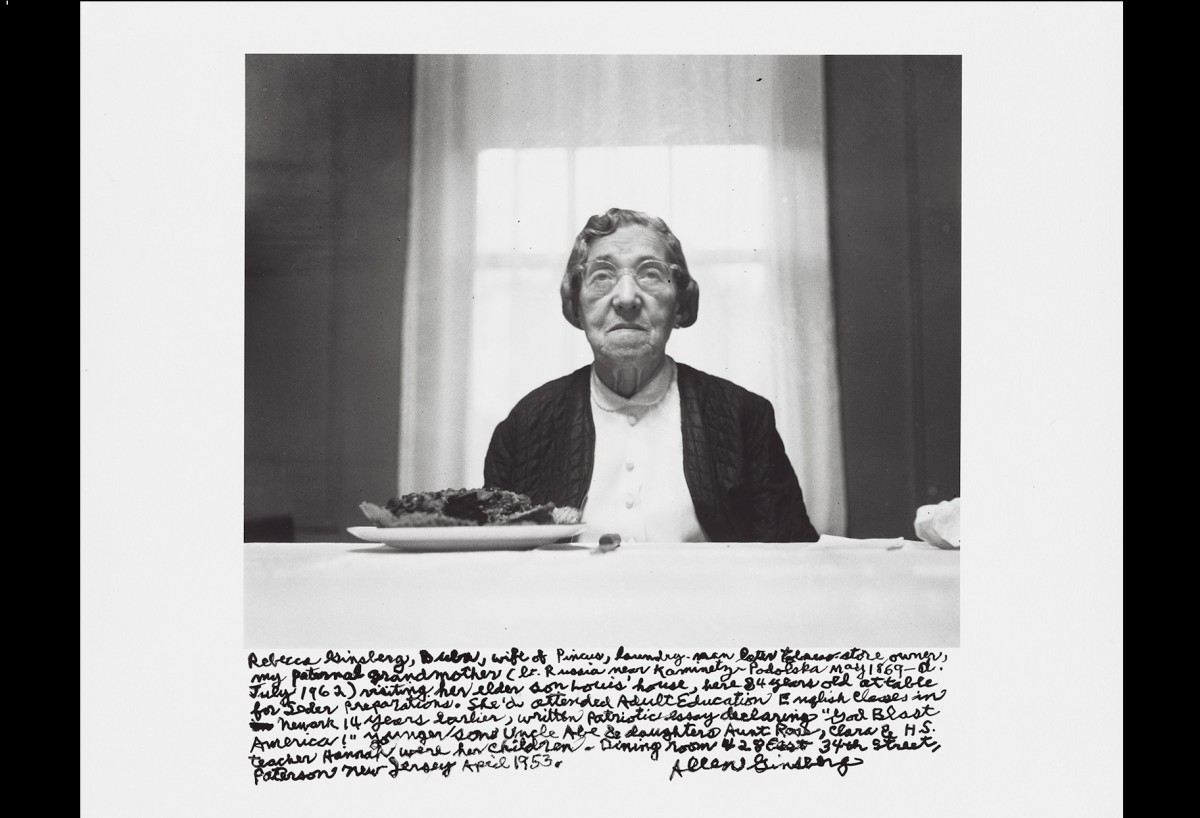

One of the few family photos is that of Allen’s paternal grandmother, Rebecca Ginsberg, wife of Pincus, who sits unsmiling at the family Seder table in her Paterson, New Jersey dining room. In the caption, we learn that “She’d attended Adult Education English classes in Newark 14 years earlier,” where she wrote a patriotic essay declaring: “God Blast America!”

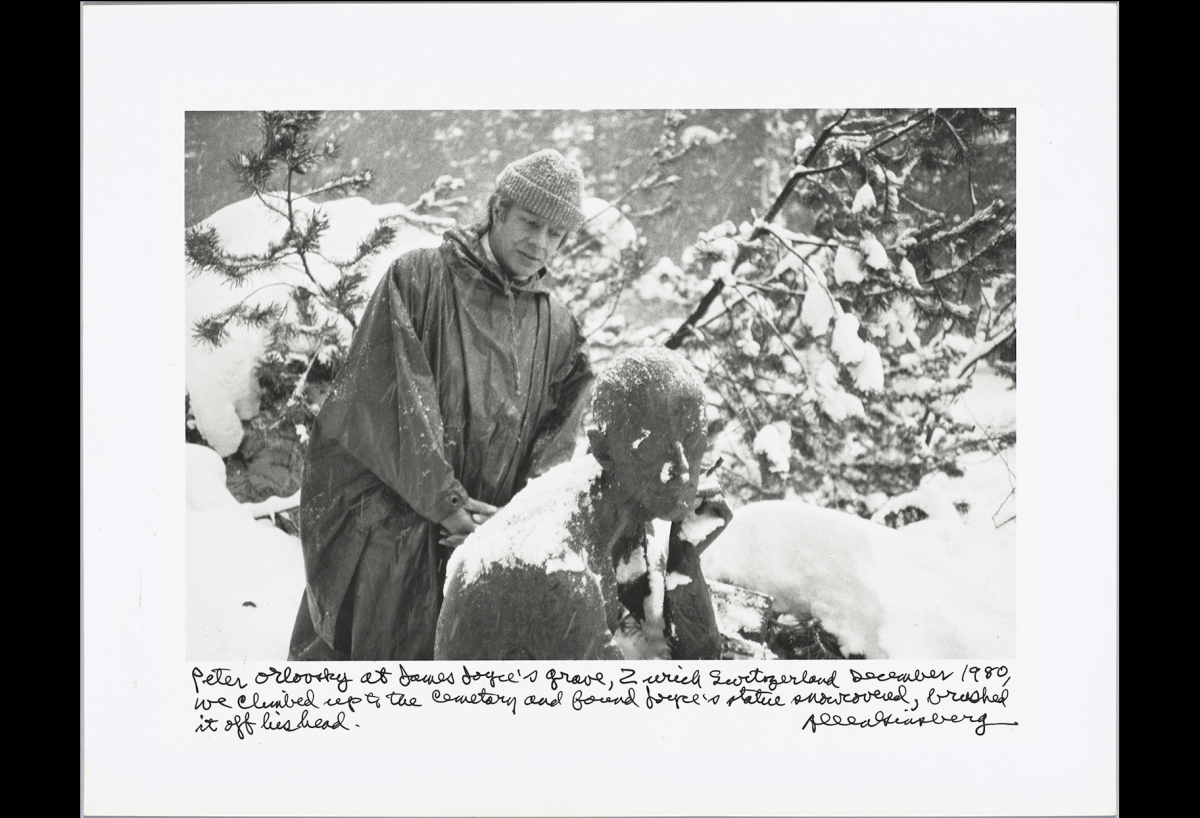

There is a snapshot of Peter Orlovsky, dressed in a dark jacket, walking on a beach, and one, shot by Orlovsky, of Ginsberg, Al Sublette and Henry Schlactner sharing a meal at Foster’s Cafeteria, included as both a snapshot (1955) and a larger format image (printed 1984-1997). The adjacent shiny table top takes up the bottom half of the photo, and we lose the top of Ginsberg’s head. All three, seem to be interrupting their coffee and conversation, turning for just a moment to face the camera.

We see Ginsberg’s apartment at 1010 Montgomery Street in San Francisco, on one wall a poster for the Mass in B Minor. The room is dark and fairly orderly, with a metal pencil sharpener resting upon a pile of books. There is a photo of Neal Cassady (smoking a cigarette) with a car salesman, standing in front of a Packard with an airplane hood ornament, included in the exhibit as a snapshot from 1955 and as a larger format print (1984-1997) to accommodate the caption. The setting is a North Beach used car lot and Cassady, Ginsberg writes, “needed new wheels.” Cassady is twenty-nine years old and a “Bay Area Johnny Appleseed of pot,” a man who:

The words illuminate Cassady. They spill forth, cascading in phrases, in a literary style we recognize as quintessential Ginsberg.

“I am sorry you have read Howl. I am sorry it was published, and I don’t feel I am friends with Allen either.”

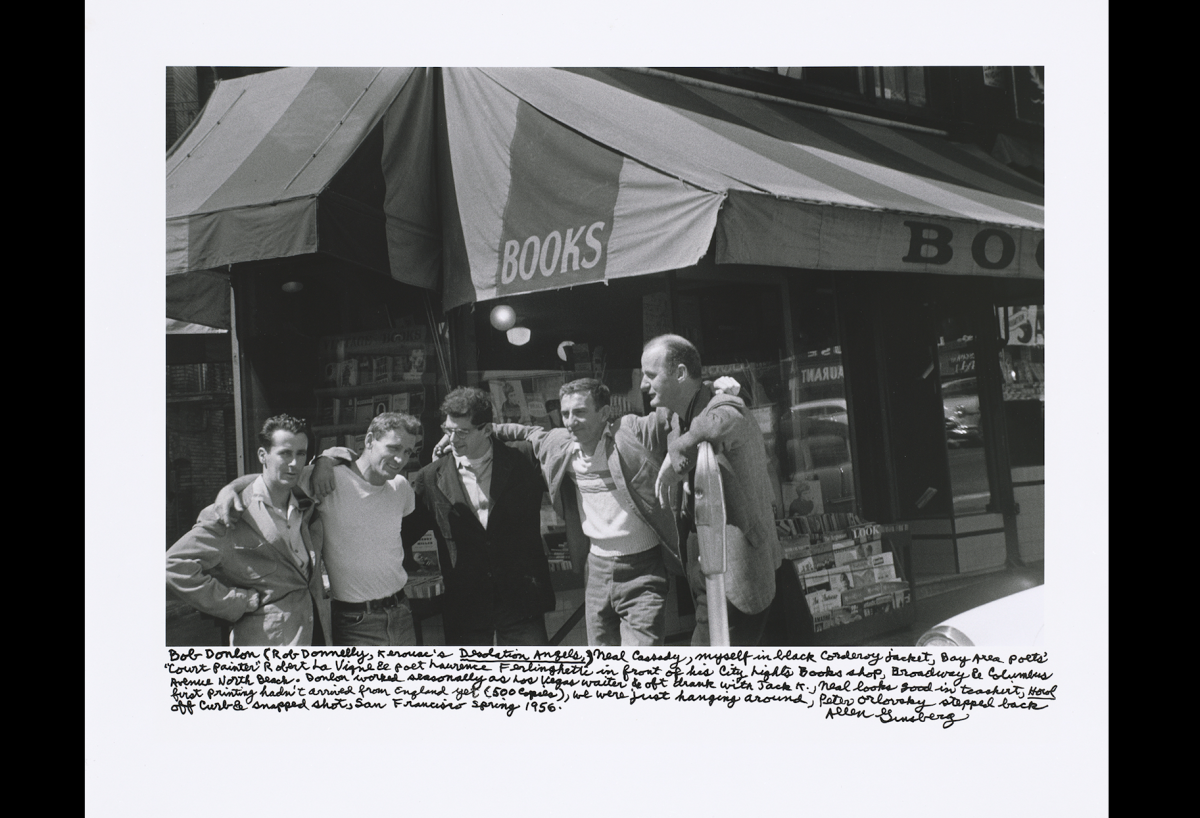

In another group photo, Cassady, Bob Donlon (Rob Donnelly), Kerouac, Ginsberg, Robert La Vigne, and Lawrence Ferlinghetti stand in front of his City Lights Books shop. Ginsberg’s words fix the moment:

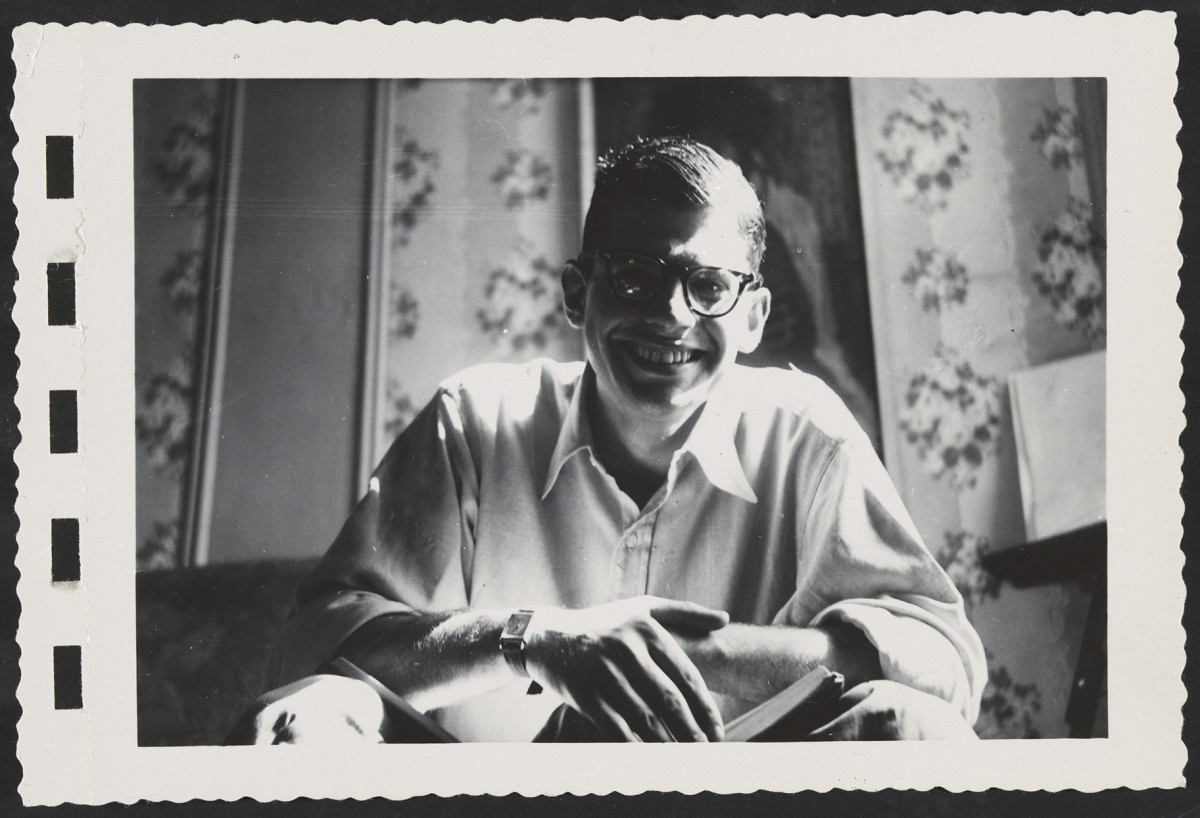

Passed back and forth among friends and even handed over to a few outsiders, the inexpensive little camera caught them celebrating life together—not at the big historic moments like the first reading of Howl but rather casual moments when they were eating, sleeping, traveling, and just plain hanging out. There are compelling images of Ginsberg shot by William Burroughs, Ginsberg on the roof of his Lower East Side apartment, between Avenues B & C, and Ginsberg smiling broadly (Bill must’ve said something….). In the full caption to the latter, Ginsberg adds a detail that gives the image special meaning: they were taking snapshots of each other on the same couch.

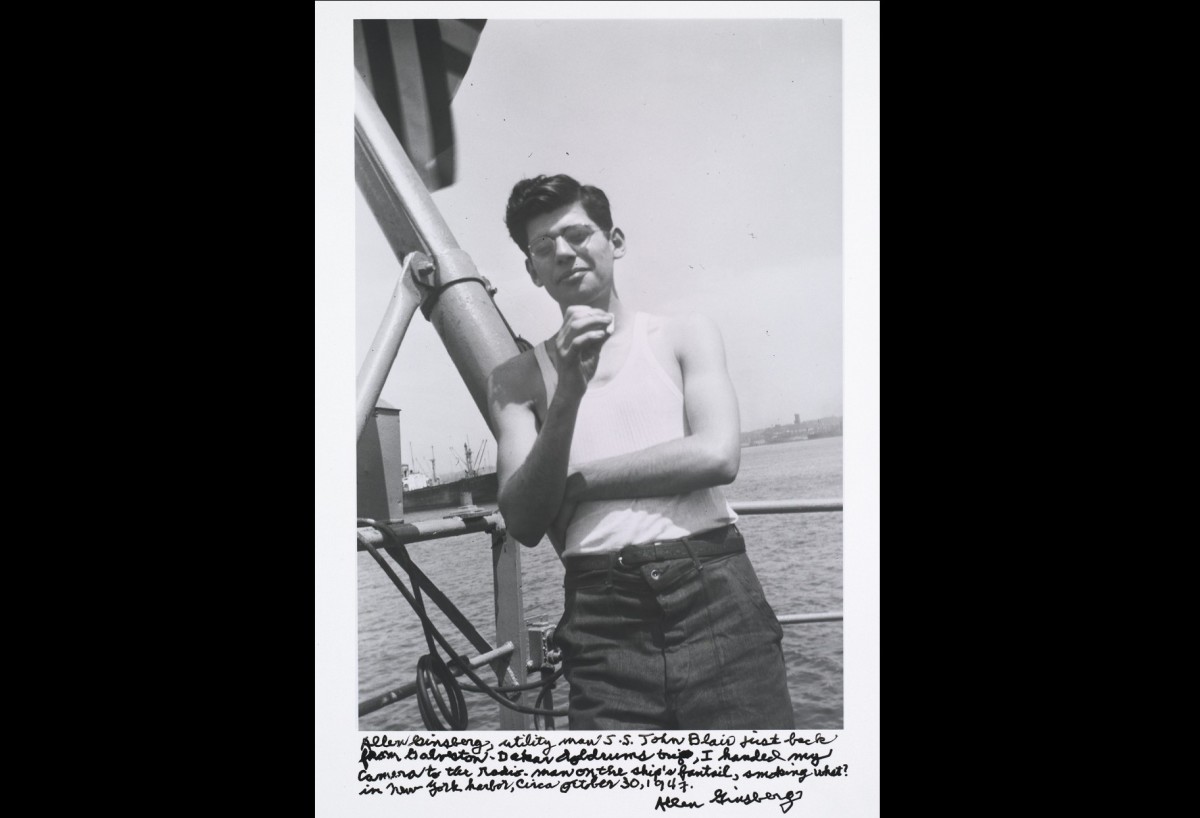

There is a striking photo from 1947 of a very young Ginsberg, Allen Ginsberg, utility man just back from Galveston… in his undershirt aboard the S.S. John Blair. The caption explains: “I handed my camera to the radio-man on the ship’s fantail, smoking what? In New York harbor, circa October 30, 1947.” A descriptive caption, transformed by the words, “smoking what?”

To the original Beat Memories show from the National Gallery, the Grey added fourteen photographs and all of the materials in the vitrines. “The National Gallery show was a bit small for our space,” explained Lynn Gumpert, Grey’s director who selected new images from the Howard Greenberg Gallery, twelve without text and two with captions. The additional works were hung in the show, often to create pairings or groupings. A powerful print of Allen Ginsberg & Gregory Corso, modest & immodest self-portraits, Tangier (1961) showing the two of them hiding and not hiding their penises, is placed near two phone booth photos of Ginsberg and Corso and a closeup of Gregory Corso and myself double-portrait Siamese poetry twins (1961). Three self-portraits from the 1990s, Ginsberg in Vilnius (1985), in Prague (1993), and Ginsberg at the optometrist in New York City (1994) give us a sense of a more mature Ginsberg in his 60s and 70s.

Interns from the Grey Gallery were sent to the Fales Library with a list of every photograph in the expanded show and they were directed to see what they could find. “We thought that we would fill two or three vitrines but we came up with four dynamite vitrines,” said Gumpert, including one with the first handwritten manuscript for Ginsberg’s Kaddish (1961), his remarkable tribute to his mother, Naomi.

It is not a howl. It is not a rant. Rather, it is a long exhale, a deep sigh.

The archival materials add much to the original show. Like the captions, they provide the viewer with context and history—some adding clarity, others mystery. A 1962 note to Cordula von Koschembahr, Ginsberg’s wealthy friend, from Carl Solomon (to whom Howl was dedicated) says, “I feel that our relationship is at an end. I am sorry you have read Howl. I am sorry it was published and I don’t feel I am friends with Allen either.” Why this was the case remains unclear.

There is a first edition of Howl and Other Poems (1956), published by City Lights Books and one of Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), published by Viking Press. There is a mass-market paperback edition of On the Road from 1958, on its cover a young man in a striped tee shirt, a bandana round his neck.

The collaboration with Fales, with its special Avant Garde and Downtown collections, is a powerful one for Grey which has strength in The New York School. They have successfully joined forces on three previous shows, Downtown, Downtown Picks, and Toxic Beauty: The Art of Frank Moore and will next be collaborating on Creating Downtown—a show about the 1950s and 1960s, stopping around 1974. “The art world seems to have discovered archives about ten years ago,” said Marvin Taylor, Director of the Fales Library, who began their Downtown collection in 1993, following in the footsteps of Mel Edelstein and Ted Grieder.

“We have things that were thought of as archival and are now thought of as art—a lot of things in that grey area between finished work and drafts,” Taylor said. “The Beat Memories exhibit shows the coterie of people Allen Ginsberg knew but we see the coterie in a different way in the archival material,” Taylor added. “We have both sides of correspondence, for instance, and collections constantly complement each other and alter each other’s meaning.”

After closing on April 6th, the part of the exhibit from The National Gallery will travel to the Contemporary Jewish Museum in San Francisco, where it will run from May 23rd to September 8th. Only New Yorkers, however, will be able to see the rich archival material drawn from the Fales Library. Published as a companion to the show, though, is a fine catalogue with a superb essay by Sarah Greenough and a reprint of Thomas Gladysz’s 1991 interview with Ginsberg for Photo Metro, which followed the exhibition of Ginsberg’s photographs at the Robert Koch Gallery in San Francisco.

In the end the Grey exhibit: Beat Memories: The Photographs of Allen Ginsberg is a quiet and compelling show—private and personal. It is not a howl. It is not a rant. Rather, it is a long exhale, a deep sigh.

For information on programs related to Beat Memories, see Grey Art Gallery website:

Beat Memories Programs.

In addition to Guernica, Roslyn Bernstein reports on arts and culture for such online publications as Buzzine and Huffington Post. Bernstein is a professor of journalism at Baruch College, CUNY and the CUNY Graduate School of Journalism. She is the author of Boardwalk Stories and the co-author of Illegal Living: 80 Wooster Street and the Evolution of SoHo.