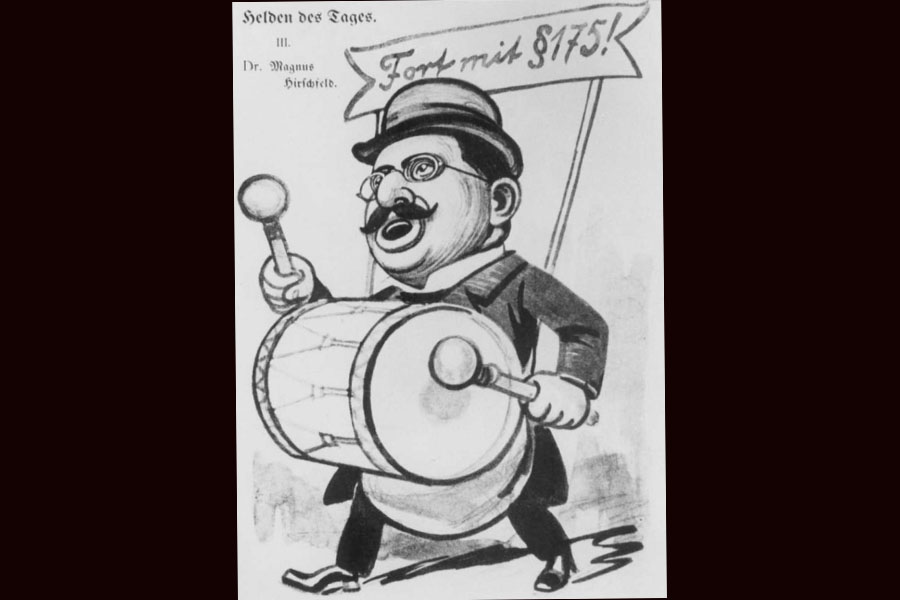

A 1907 political cartoon depicting sex-researcher Magnus Hirschfeld drumming up support for the abolition of Paragraph 175 of the German penal code that criminalized homosexuality. US Holocaust Memorial Museum Photo Archives

By Roslyn Bernstein

Curator Ted Phillips, Director of Exhibitions at the William Levine Family Institute for Holocaust Education at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, DC, was in town recently to open the Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals 1933-1945 exhibit at the Museum of Jewish Heritage. It’s an exhibit that has been traveling since the fall of 2002—this is a show that has been on the road for more than a dozen years. The Museum of Jewish Heritage is its fifty-second US venue but, remarkably, the first time that the show has been seen in New York City.

How is this possible?

Originally, the exhibit was planned as part of the Holocaust Memorial Museum’s effort to show that Nazi ideology “targeted a range of victims,” says David Marwell, the director of the Museum of Jewish Heritage, who in 2000 was an Associate Director at the Holocaust Museum. “The whole idea behind the show was to deepen people’s knowledge about the Holocaust.” The Museum conceived of an educational series on the non-Jewish victims of the Holocaust, including the disabled, Roma, Jehovah’s Witnesses, non-Jewish Poles, Soviet POWs, and homosexuals. During the early 2000s, though, the Museum changed its focus, and only the exhibit on homosexuals was completed.

Curator Ted Phillips began working on the exhibit in 2000. Phillips, a historian with a PhD in Russian and early modernist history, who had taught Russian history at various colleges, asked himself, “Where do I begin?” He had no idea how to write an exhibition.

So, like many a trained historian and talented fiction writer, he devised the idea of developing a narrative and then finding objects to illustrate it. He was influenced by Heinz Heger’s (Josef Kohout’s pen name) book

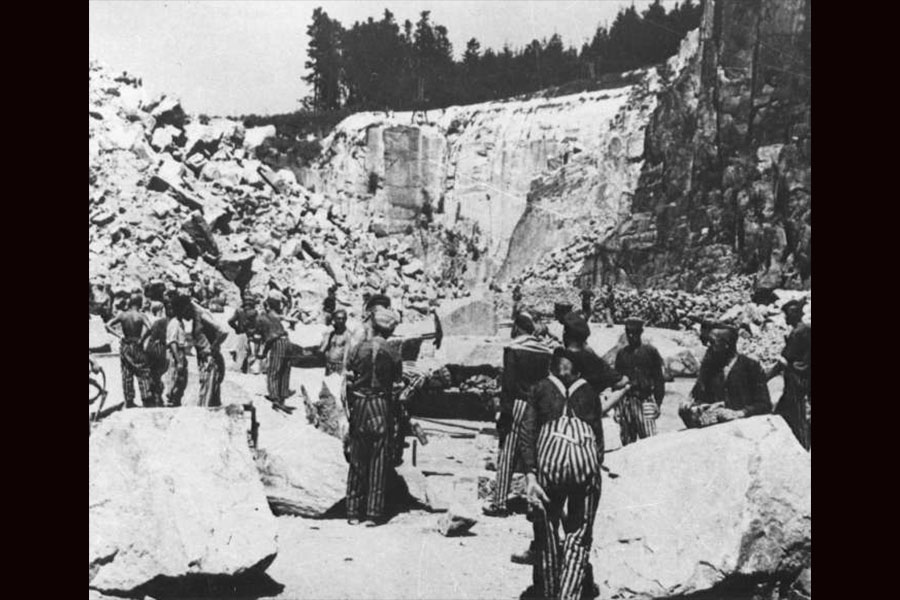

The Men with the Pink Triangle is a first-person account of his arrest and imprisonment for being a “degenerate.” A Viennese university student, in 1939 Heger was arrested and transported to Sachsenhausen, a concentration camp north of Berlin. He was ultimately reunited with his family after the Americans liberated the camp in 1945. The book documents not only the suffering he experienced at the camp but the poor treatment that he received after liberation from the West German government. After he died in 1994, his companion donated fragments of his diary, a number of letters, and a cloth strip with the red triangle and his prisoner number to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.

While the narrative Phillips was constructing got longer and more nuanced, increasingly he faced a challenge. An exhibit must show things, but there was virtually nothing in the museum’s collection, with the exception of a few pink triangles that were not connected to anyone, that he could use. Another constraint was that the exhibit had to be a panel show of less than 100 linear feet.

Beyond words, what was Phillips to show? There were iconic Holocaust objects: the rail car used to transport Jews that museum-goers walked through, the star with the word “Jude” written on it, and, of course, the shoes—each individual shoe representing a victim. These objects, however, weren’t things he could use for his exhibit.

Artifacts were hard to find, Phillips says. Laws against homosexuals did not come off the books in Germany until 1969.

But where does one start in the modern age? Phillips’ answer was direct: “You start on Google.” Within seconds, Phillips found another exhibit: Verfolgung homosexueller Manner in Berlin 1933-1945, put on by the Schwules Museum (Gay Museum) in Berlin. One part of the exhibit was held in East Berlin, and one part was in a memorial hall at Sachsenhausen. Phillips spent a week in Berlin in 2000 exploring their collection, which became the primary source for the images of documents and some of the photographs in his exhibit. Artifacts were hard to find, Phillips says. Laws against homosexuals did not come off the books in Germany until 1969, “so gays there hid stuff after the war.” Simply put, they were afraid of further punishment.

The Nazis did not, Phillips says, look at gay men as amoral. Rather, they saw homosexuality as a weakness, a disease.

In his research, Phillips came across a December 17, 1935 news story in The New York World Telegram, not the paper of record, with the headline, “Hitler Jails 500 in Morals Drive.” The piece focused on Hitler’s quest to purge the Reich of sexual abnormality.

The Nazis did not, Phillips says, look at gay men as amoral. Rather, they saw homosexuality as a weakness, a disease. They estimated that there were two million gay men, a number that affected population policy. Lesbians were not officially persecuted although Nazi ideology saw women as wives and mothers. The main idea was that if there were no gay men, lesbianism would disappear and the population would increase.

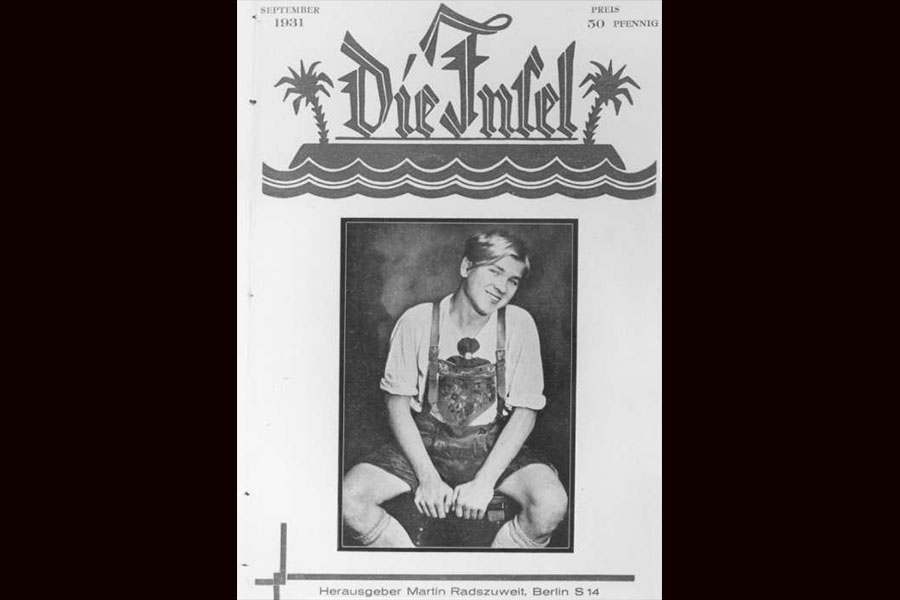

Only when Hitler came to power in 1933 did the Germans begin to enforce Paragraph 175 of the criminal law code, which banned homosexual activity, described as an “unnatural indecency between men.” While the law had been on the books since 1871, little had been done to punish homosexuals. By the early 1930s, however, it was estimated that there were 350,000 homosexual men and women residing among the four million inhabitants of Berlin, a number that alarmed Hitler. In early May of 1933, the Nazis attacked Magnus Hirshfeld’s Institut fur Sexualwissenschaft (Institute for Sexual Research) in Berlin, burning many of its books and archives.

Research into Gestapo records reveals that Gestapo officers were merely “desk jockeys,” Phillips says. People went to them to denounce men who were gay. One man was denounced by his sister. Another man by the mother of a partner. “One did not know who one’s friends were.” Included in the exhibit is a file photo from 1938 of an alleged gay bar. “Clearly,” Phillips says, “some surveillance was going on.”

Another photo reproduction illuminates the fact that gays often got involved in protective marriages to avoid persecution. The photo is particularly powerful, since the two men, the real couple, are seen in sharp focus while the “wife” of one of them, standing behind him, is a blurred figure.

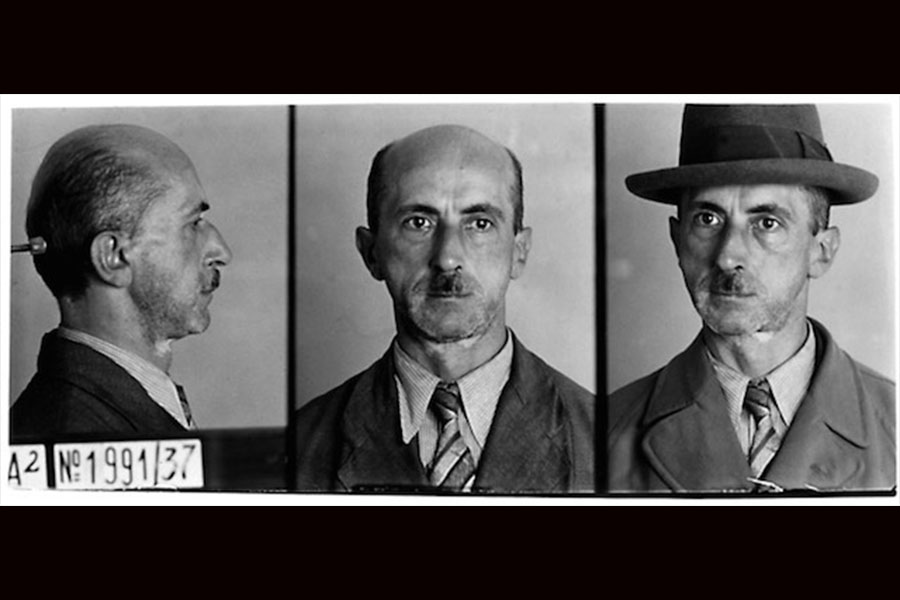

There are police photos from 1933-1945 of some of the 100,000 German men, mostly Aryans, who were arrested.

As the head of the SS, Henrich Himmler, according to Phillips, was the real bad guy. He pursued the enforcement of the criminal law codes. A document from 1936 deals with the creation of a secret office to combat homosexuals and abortion: both threats to the population growth that the Nazis advocated. There are police photos from 1933-1945 of some of the 100,000 German men, mostly Aryans, who were arrested for violating Paragraph 175. Early on, punishment was less stringent, but after 1935 more than half of those arrested were convicted. A chart for June, 1937 lists 281 German men in twenty-four cities arrested for homosexual crimes; 112 of them were from Berlin. Julius Enoch was arrested for violating Paragraph 175 in July, 1938. Had it been a few months later, he would have been arrested because he was Jewish. Enoch died in Sachsenhausen in 1942.

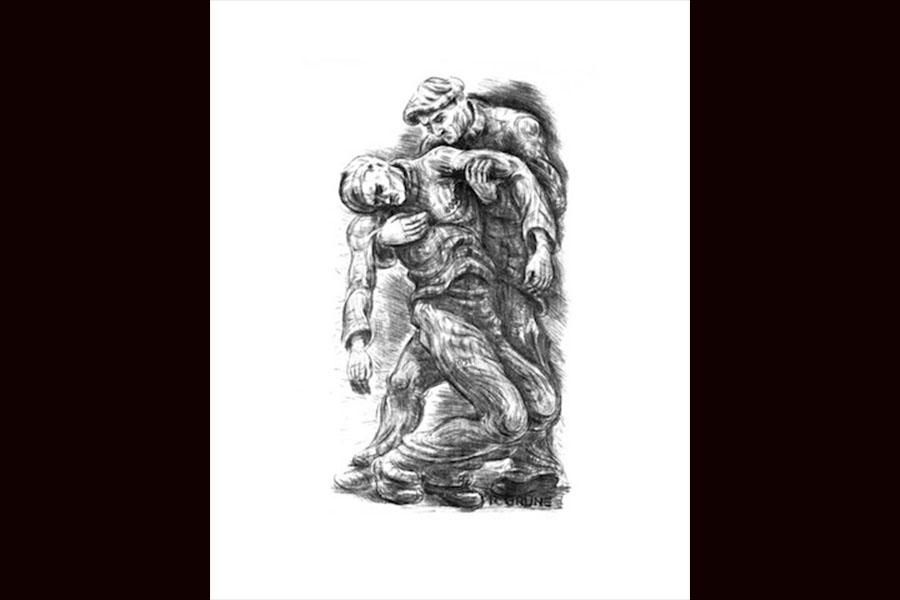

Although Phillips identified charts and documents, which could be reproduced, photographs were harder to find. Included in the show are reproductions of lithographs by Richard Grune, a Bauhaus-trained artist, who was arrested, sent to prison, and then to the camps. Grune survived and was liberated at the end of the war.

The exhibition has traveled virtually unchanged since it was first shown in the fall of 2002. Although Phillips altered one panel to reduce the number of document images in order to enlarge the remainder for better legibility, the others are the same—despite more than a decade of new research. “While there has been continuing scholarship in the history,” Phillips says, “most of it addresses local-level implementation/persecution that has not fundamentally affected the overall storyline presented in the exhibition.”

To date, the exhibit has appeared in twenty-seven states and thirty-nine cities. Interestingly, few of the venues have been museums, possibly because it is a panel show, heavy on text. Far more common venues have been public and university libraries, several Jewish or LGBT community centers, and a couple of small art galleries. In collaboration with Gay Zagreb, an arts and culture organization in Croatia, the exhibition text and imagery (though not the panels themselves) appeared in translation in several East European countries.

Although the United States Holocaust Museum has had a traveling exhibitions program in place since the early 1990s, “we’ve found it very difficult,” Phillips says, “to find New York City venues for any of our exhibitions.” The Museum of Jewish Heritage has hosted three previous exhibitions, in 2006, 2011, and 2015. This exhibit, however, is the first time that the museum has taken a panel show that did not contain artifacts. There have also been three others traveling shows in New York: to the Museum of the City of New York (1991), the Jewish Museum (1997), and the United Nations headquarters (2009).

Winding up his presentation on “Curating Invisible History,” Phillips told the audience at The Museum of Jewish Heritage that, although he has worked on over forty five exhibitions since joining the US Holocaust Museum, Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals is the one that is most important to him. In an emotional finale, he cited three reasons: “It is closest to my heart as an historian; it is closest to my heart as a museum professional; and it is closest to my own life as a gay man.”

Then, turning slightly away from the mic, he chokes up, adding: “This could have been me.”

Nazi Persecution of Homosexuals 1933-1945 runs from May 29 to October 2, 2015 at the Museum of Jewish Heritage in New York City.