Ariamna Contino and Alex Hernandez Duenas, Militancia estetica at 331 Studio. Photograph courtesy Shael Shapiro.

Four years ago, in November 2011, I joined a group from the Corcoran Gallery in Washington DC on an art tour of Cuba. I was a reluctant groupie, lured by the promise of an easy visa and prearranged art contacts. I signed on to the adventure, a week-long trip to Havana, Trinidad, and Cienfuegos, knowing full well that I would have little or no Internet when I was there and that I would have to follow, for the most part, the group itinerary.

We stayed at the Parque Central Hotel in Havana, walking distance from the old town, one of several tour groups that marched through the lobby: Europeans, Canadians, and a few Americans. Among them, a group of baseball players in their 60s, in town for a game against Cuban seniors. One evening, nursing a mojito in the lobby, I spied several of them heading out on the town with four dazzling local prostitutes. One of them waved to the concierge as he left. The doorman held the door open, his hand extended for his tip, as they exited.

We toured the Museum of Fine Arts and visited several home studios where artists were selling their work directly to the art-loving, art-touring public. When I returned, I published a piece on the journey in Art Critical with the headline: “Report from Havana: Where Artists Are Richer than Doctors.”

January, 2016, one month after President Obama announced the restoration of relations between the United States and Cuba, I arrived in Havana for a second visit, a week-long group tour with The Nation, once more based at the Parque Central, and a second week, on my own, in Casa Colonial Cary y Nilo in Central Havana, a ten-minute walk from the hotel. I had done my best to set up interviews with artists, gallery directors, and arts professionals in advance through email, but despite some success I quickly realized that most of the work still had to be done when I hit the ground.

Much had transpired in four years. American tourists were flooding the city; several experts reported that authorized US visits to Cuba rose 50 percent in 2015. Overall, more than 3.5 million tourists visited the country last year. Signs for private apartments or casa particulars were everywhere, on freshly painted buildings in the historic district and on dilapidated buildings, their concrete terraces braced with wood to prevent them from collapsing, in south and central Havana.

La Guarida, the private restaurant that I remembered from 2011, perched seventy steps up in an unrestored building where men played dominos on the street level and then number two on Trip Advisor, was now listed as number sixteen (although I still found the food exceptional and rank it at the top of my list). The building was undergoing a complete renovation, a romantic rooftop bar already open. The political billboards that lined the highways outside of the city were almost all gone, a change that reflected orders from higher up. Young people clustered everywhere, kids with scratch cards, trying to get connected at Wi-Fi hotspots.

While the average Cuban’s monthly wages in 2014 was still only $25, the shift to the private sector was already significant. More than 40 percent of the labor force now holds non-state jobs.

While the American embargo was still very much in place, Raul’s 2011 guidelines on economic and social policy, permitting the sale of homes and cars, increased remittances from family abroad, easier travel, and shifting employment substantially from the state to the non-state economy, clearly had taken effect. A sign of the changing mindset, letters of complaint from ordinary Cubans now appeared in the Friday edition of the Communist party paper, Granma.

While the average Cuban’s monthly wages in 2014 was still only $25, the shift to the private sector was already significant. More than 40 percent of the labor force now holds non-state jobs—waiters, tour guides, bartenders, hair dressers, restauranteurs, and taxi drivers. The resulting dynamic was a challenge to traditional Cuban socialism, in which the accumulation of capital was illegal. Income inequality was growing and there was a new push from the government to subsidize poor Cubans (not all Cubans, as was done in the past with ration cards). The idea was being advanced to develop some sort of welfare system, a subsidy targeting the poor.

Meanwhile, according to Marc Frank, an American journalist for Reuters based in Havana and the author of Cuban Revelations, “Artists and intellectuals continued their leadership role in the vanguard of the grey zone”—that area of uncertainty or indeterminacy which was being dramatically defined and redefined daily.

An artistic grey zone exists where the landscape is littered with older templates and newer configurations, where progress means halting steps backwards, forwards, and sideways, circumventing rules and regulations in a country filled with talented, trained artists, on an island where the Socialist government historically looked the other way about things artistic but where there is still no real art market, few supplies for artists, and a limited number of official state galleries.

Unofficially, art, both professional and amateur, can be found all over Havana these days: decorating the walls of upscale paladar restaurants, the slick business cards of the artist stacked nearby, and hanging in the lobbies and mezzanines of hotels like the Habana Libre, the former Havana Hilton, where paintings and drawings crammed side by side vie for tourist’s attention, each priced in US dollars and where sculptor Juan de la Tejera Chillon sits in the lobby with his carved mahogany pieces, an eager salesman, ready to make his pitch to passersby.

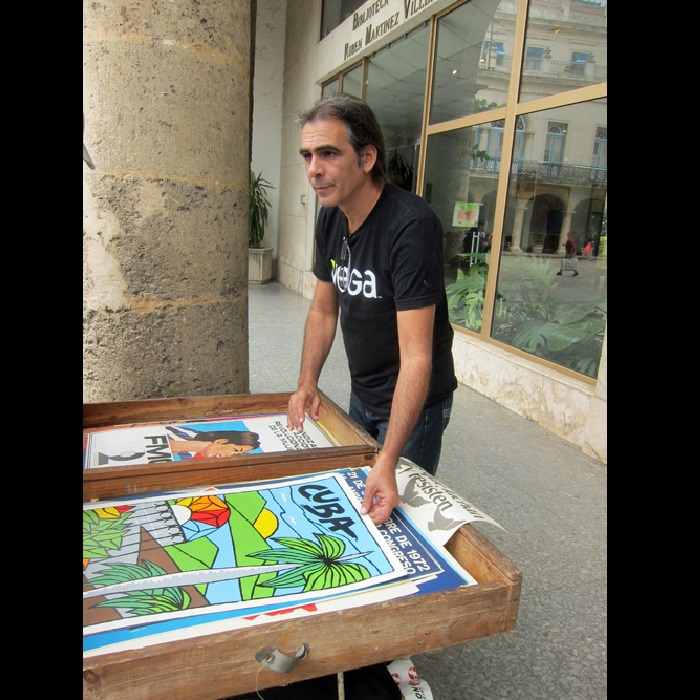

Art is threaded throughout the city, inside gift shops along Obispo Street and in stores off the Plazas des Armas, where small paintings of vintage cars, portraits of Che, seascapes of the Malecon wall, waves crashing over the barricade, and political posters sell for between $30 and $100. Or, on a grander scale in Feria Artesanal Nave San Jose, the huge warehouse down by the harbor, where, adjacent to hundreds of booths staffed by aggressive souvenir vendors selling hand crocheted tops, Tee shirts, and beaded bracelets, artists, or their friends and relatives, sell their work directly to the public: modest watercolors by Asmany Gonzalez Cabrer’s ten-year-old son Pablo priced at $8 to $10 are arrayed alongside Cabrer’s own graphic works, priced at $50 to $75. Original oil paintings and engravings sell for as little as $40 to collectors who purchase tubes for another $3 and carry them back home in their backpacks.

Beyond the art scene pitched to tourists, however, is the official grey zone, where state-owned and -run galleries like Galeria Habana, one of only four or five in Havana and the oldest one in the city, struggle to replicate the model of the modern international gallery in an environment of limited connectivity and restricted budget. Up in January was an exhibit by Ivan Capote, a gallery artist trained at the premier art school in Cuba, Institutio Superior de las Artes (ISA), whose work plays on the meaning of words in Spanish and English. Four of five pieces in the edition of “The Western Mantra,” a sculpture with the upper case letters OWN supported by incense sticks, a play on the sound of the mantra OM, had already sold at $5,000 each, and the last piece, destined for the Armory Show in New York City, is now priced at $6,000. Another work, “Chain Link Fence,” which sold internationally, is priced at $25,000.

Galeria Habana takes a commission of 40 percent and payment for pieces from Americans must be wired to Canada. They are a public company and pay taxes to the Ministry of Fine Arts. Despite government support, running the gallery is not easy. Director Luis Miret Perez pointed to space where a missing piece was supposed to be, a clock, explaining that in Cuba art works were often not fabricated on time for exhibits and, even though it was just one week before the show’s closing, he was still awaiting the arrival of the exhibition catalog, as well as the clock.

Galeria Habana was accepted to this year’s Armory Show on Pier 94. It was a very specific application, Miret explained. “We had to describe in detail which works would be in the booth for the first day.” Prominent among the pieces is Adriamna Contino’s cut-paper portrait of Obama, from her series “Apnea,” which included portraits of political heads of state from Germany, Russia, China, and Qatar. The Obama piece, priced at $20,000, took three months to complete.

For Miret, it is a major breakthrough. Having previously done four or five fairs every year, he would be happy to concentrate on two big ones, the Armory Show and Art Basel in Miami. “I hate the fairs,” he said. ”Art loses in the fairs. In Art Brussels, in the main pavilion, there was a really big gallery, surrounded by sharks. We were the little “glue fish”—el pez pega,” he said. “I suppose that this will be true in the Armory, too.”

“It’s kind of a jungle where everybody does what they want to do.”

Nelson Herrera Ysla, an art critic and curator at the state-run Centro de Arte Contemporaneo Wilfredo Lam who regularly conducts tours of the collection at The Museum of Fine Arts to supplement his income, includes Galeria Habana on his short list of artistic venues worth visiting in Havana. Herrera holds strong views on the future of Cuban art spaces, public galleries (only state-owned spaces can use the title “gallery”), and private studios, often home-based. “Cuba is a poor country,” Herrera said, “and there are still no big galleries like Barbara Gladstone in New York City. Everything is difficult here, including how to ship art. In Havana, you can still roll the canvas, put it under your arm, and carry it away,” Herrera explained, adding that Cuban artists are not used to respect. “It’s kind of a jungle where everybody does what they want to do.”

Opened in 1984, the Wilfredo Lam Center, named for Cuba’s most prominent artist, had as its main goal to create and run the Havana Biennial. They succeeded. The Biennial is now a major art world event, with planning for the thirteenth Biennial, to be held in 2018, already underway. “Planning the Biennial really happens by magic,” Herrera explained. In the old days, he called Cuban artists via embassies, and sent telegrams and teletype, often imploring recipients to: “Please give this message to the artist.” Nowadays he sends email, although he feels handicapped because he has to use an old version of Outlook Express. “We sometimes get information in the morning but have to wait until midnight to answer,” he said. Herrera also revealed that his office has yet to acquire a printer.

As a cultural institution related to international contemporary art from Latin America and the Caribbean, Centro Wilfredo Lam receives government support from the Ministry of Culture, although funding over the past fifteen years has decreased.

At one time, the Center had a travel budget of $20,000 or $25,000 from the Ministry of Culture, but this disappeared fifteen years ago. Herrera encourages friends and fellow curators around the world to invite him to their exhibits since there is no money for travel and research in the extremely modest Center budget. (The Center has had a budget of between $100,000 and $150,000 over the last five or six years to support their staff of 50.) So Herrera is off to Colombia in May where he is planning a Cuban art exhibition and staying on to research Colombian Art. He hopes to be in New York City this fall, touching base with artists and gallery curators and scouting for talent, especially among younger artists. While the older generation of Cuban artists, for the most part, did not paint the Revolution, the younger generation, Herrera explained, is making “political art in a new way. They hide their politics and they use a kind of metaphor for the ruins of Havana.”

Young Cuban artists have a friend in the Ludwig Foundation of Cuba (LFC), where Executive Director Wilfredo Benitez Munoz describes the major role the Ludwig plays in supporting artists after their graduation from art school. A public, but not state-owned, venue, the Ludwig Foundation was established by a deft sleight of hand, using antique civic code from Spain that recognized the existence of foundations and associations.

Founders Peter and Irene Ludwig were art collectors and art historians from Aachen, Germany who collected important twentieth century art: American Pop art in the early 1960s, Picasso and Soviet art in the 1980s. In 1990, after seeing a Cuban show where the art was not for sale, the Ludwigs, who had established Ludwig Museums in Aachen, Cologne, and Vienna, became interested in Cuban art. They wanted to create a museum in Havana, endowed by the Cuban government.

Collecting Cuban art was a good platform, Benitez said, a way for them to expand their collection to the third world. As it turned out, the timing was bad. The Soviet Union had collapsed and Cuba was mired in the dire economics of the Special Period. “But, with the invaluable assistance of Armando Heart, one of the Ministers of Culture who saw a need to create a civil society, the Ludwig Foundation in Cuba was founded. “The idea was visionary,” said Benitez, “to create a foundation to support emerging Cuban artists who the state could not support.”

Since its inception, the LFC has found a smart and unique way to provide assistance, not by selling art or by functioning as a museum with rotating exhibits but by creating an entirely new model. Young artists, straight out of art school, are invited to display work for one day. “We do not focus on finished pieces of art but rather on the process,” Benitez explained. “Then, there is a lively debate between the artist and the audience.” Ludwig has used the same model with filmmakers and has begun expanding the program to include young architects, who are now serving the newly emerging entrepreneurial sector. Architects are considered engineers and they do not have the freedom of artists. Still, Ludwig is inviting them in to show projects and discuss their relationships with their clients. “Their situation is new,” Benitez said, “and we need to provide them with a platform.”

Currently, the Ludwig is not only working with young artists but studying the way creativity develops in Cuba by looking at the weekly El Paquete, a terabyte of content that somebody downloads free from the web and distributes cheaply all along the island. Initially, the pirated package included films, TV series, games, music, and software that the majority of Cubans consume, but Ludwig has been studying the contents as culture. “We have discovered that Cuban content is being included more now, video clips of bands, design magazines conceived for the package, and commercials and ads. The private sector is emerging in Cuba and this is a way to advertise their ventures. It’s all sort of tolerated,” he said.

Beyond working with artists, the LFC also designs cultural programs for visiting international students, many from the United States, with a regular contingent coming from New York University. It’s a heavy schedule, and one that Benitez predicted will only grow heavier when the embargo ends. “Our scale is limited,” Benitez said. “You come here by appointment only. It’s not consumption for everybody.”

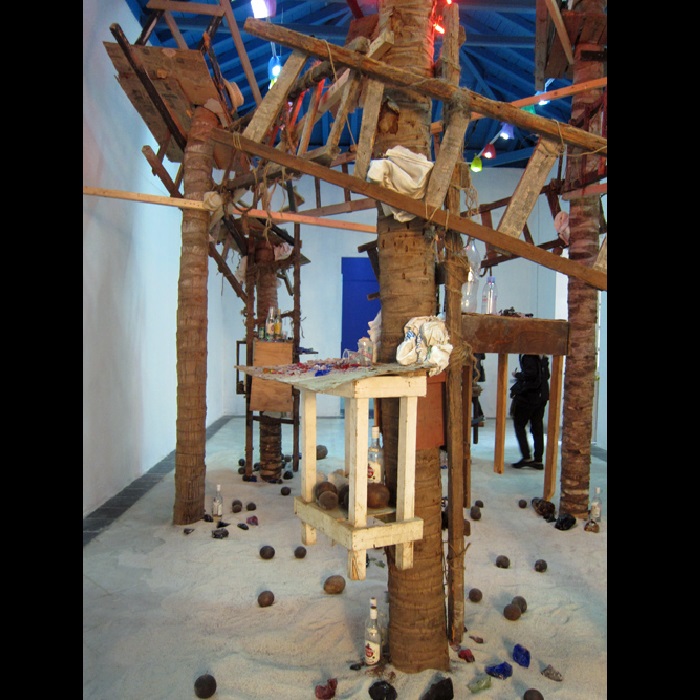

Ludwig’s model has most certainly advanced the careers of Alex Hernandez Duenas, Adrian Fernandez, and Frank Mujica, three 2010 graduates of ISA who have known each other for years. Within the past month, the gallery they co-founded, 331 Art Space, has received major media attention in the New York Times “36 Hours in Havana” and in the Wall Street Journalstory on “The American Invasion of Cuba.”

When the threesome came out of the academy, there was no institution to go to for funds, grants, or scholarships. Ludwig filled in the gap. “We were showing at Ludwig in early 2006 and before, and also helping them with shows.” As a result, they started exhibiting much sooner than most artists in Cuba and, through the discussion session, they were able to gauge how people reacted to their work. “The LFC gave us a more mature conception of the arts than the university,” said Fernandez, whom the group dubs their public relations spokesperson.

The real change came in 2001, when companies with itineraries related to art began visiting studios. “We were inserted into that dynamic,” Fernandez said. After three years in a small apartment in Miramar where they could only show visitors their works in portfolios, the scale of their work had grown and they pooled their money to buy and renovate their building, a 1941 house that had been partitioned into lots of rooms. The new studio, which opened in 2014, is providing them with a human link, a platform to connect to other galleries who might represent them—in South America, in Houston, in New Orleans, and in Europe.

Their work is bold and global. On the walls in January were several artistic collaborations between long-time couple Alex Hernandez and Ariamna Contino, who shows her work at Galeria Habana. The work, combining Contino’s hand-cut papers and Hernandez’s graphics, focuses on violence and narco states in Colombia, with black circles identifying marijuana farms and shading indicating their proximity to places of guerrilla activity. Last May, the work on drugs was included in the twelfth Havana Biennial. Nearby, a solo piece by Hernandez brilliantly juxtaposes the same prototype for two houses, one in a suburb of Havana and the other in a suburb of Miami. Hernandez, whose parents live in Havana but whose brother lives in Miami, explained: “People who live in Miami and Havana have lots of similarities. It’s the same people with the same expectations.”

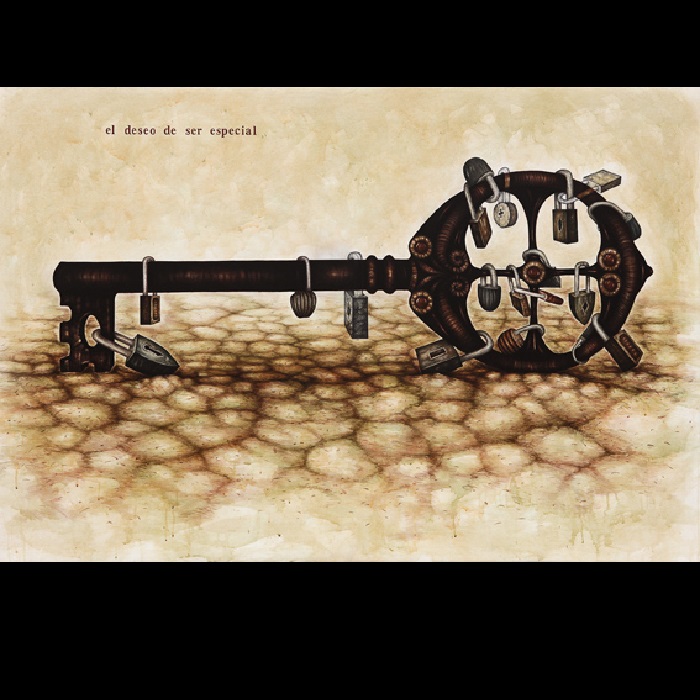

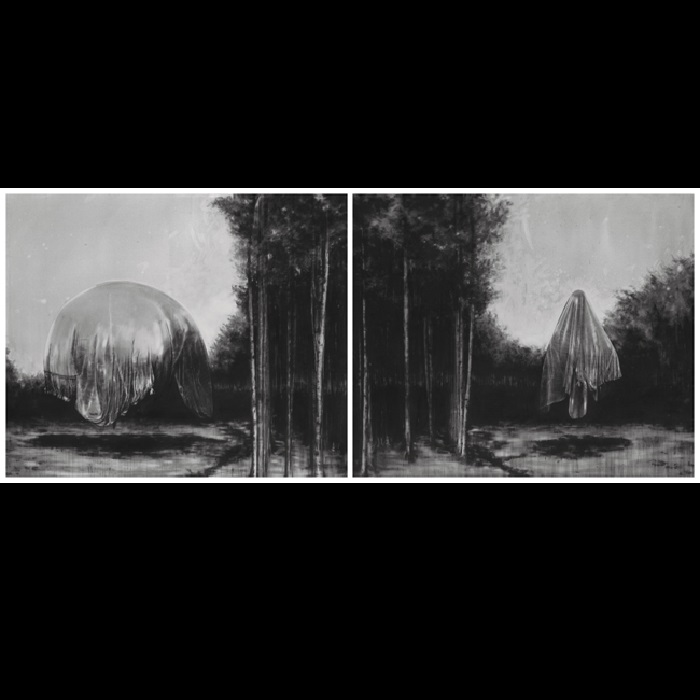

The third of the partners, Frank Mujica, is a painter whose most recent focus is pencil drawings, which he describes as “a very sincere, expressionist media.” In 2011, he began making small drawings as a kind of diary, as many as five a week. They were intimate works, each stamped with a date. But Mujica is also concerned with large works, imagined landscapes in which he uses smashed graphite and water, applying the liquid graphite to the canvas when drawing, using pencil for lines, and an eraser, or a drill with a larger eraser at the end, to alter the image. In “Ghost” we see fabric floating and, maybe, a balloon. Shown in the Havana Biennial, the work will be exhibited in April in the Ludwig Museum in Koblenz.

Photographer Adrian Fernandez works hard at creating the story behind the story. Up on display were images based on twentieth-century Cuban postage stamps from the time of the Republic. Fernandez did extensive research for this work but he does not want it to be understood as a longing for the past. “It’s not a longing for the forties or the fifties,” he said. “That would be a sad image. The reality is more complex.” After taking many photos with large format cameras, Fernandez digitized them and spent hours at a computer removing many details. Many images are off-center and the viewer experiences their texture, too. Fernandez, who teaches photography at New York University every fall semester, a job that he got after teaching photography classes at the Ludwig, brings materials from New York—paper, ink, and laminator. “I pay somebody to bring those pound rolls to Cuba,” he said.

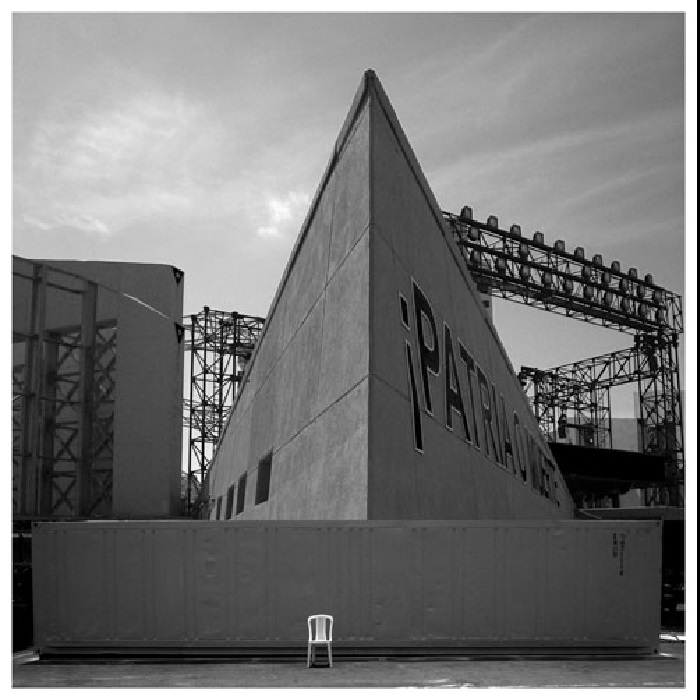

Just two blocks away on Avenida 31 is The-Merger, three artists who first showed together in the 2009 Havana Biennial. Unlike at 331 Studio, Alain Pino, Niels Moleiro, and Mayito all work together on the same piece, developing ideas in painting first and then transforming the painting into a work of sculpture. In 2011, they purchased Lavanderia, an old laundry building, which they transformed with funds from the sales of their work into a studio, and they have fixed up the Avenida 31 building as a showroom.

According to their spokesman, Sandra Borges, 95 percent of the collectors who come there are Americans, many of whom arrive in cultural groups or on organized art tours. Payments are made through offshore accounts. Sales of their work in auctions at Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Phillips over the past few years have pushed up the estimates for their work. An earlier work, a sculpture in the form of a Swiss Army knife with Cuban implements substituted for the traditional tools, has tripled in value. “Jaws of Life,” a large pair of medical clamping scissors with the outline of a shark as each of the two blades, which originally sold for $20,000, was resold for $68,750 recently at Sotheby’s.

The relationship between the United States and Cuba is like looking at your children: “You see them every day but you don’t see them grow.”

New work by The-Merger relates to historic memory, and specifically to enslaved Africans, taken from their homeland, who brought their culture with them and subsequently rebuilt it in Cuba. A painting and a polychrome red sculpture, “Remember,” both show an African head, the hair made up of flash drives. An adjacent painting shows a head with cutting pliers sticking into it, giving the appearance of an Afro. Ultimately, The-Merger will transform this image into a piece of sculpture.

Mayito, who describes himself as the “metal technical partner,” says that the relationship between the United States and Cuba is like looking at your children: “You see them every day but you don’t see them grow.” He is optimistic about President Barack Obama’s March visit and believes that the end of the embargo will resolve economic relations with the US. “Everything will be much cheaper if it comes from 90 miles away,” he said. Pointing to a two-handled saw with Statue of Liberty teeth, Mayito added: “There are two sides here, left and right. We need more than one party in Cuba. Having more than one point of view assures making the best decision. But,” he laughed, “If you get a third party in the States, we will have to remake the saw.”

While 331 Art Space and The-Merger have renovated studio buildings and broken into the sophisticated global art market, most Cuban artists continue to sell their work from modest home studios, bolstered by visits from tour groups. Edel Bordon, his wife Yamile Pardo Menen, and their son Pablo Bordon Pardo all sell their work from their studio, which has a view of the sea and is conveniently located just blocks from the Hotel Nacional and the Malecon. Bordon’s 13-year-old daughter serves as his translator, telling the crowd that her father is a Professor of Art at the prestigious Havana University. Bordon moves about the space rapidly, eagerly showing paintings to prospective buyers, then poses happily with a couple who have just decided to buy a large painting for their Chicago home.

In the States, Bordon works with Galeria Cubana in Boston, where prices for his work are double. To bring his art to Boston, though, Bordon must get special permission from the US State Department. At the end of each year, Bordon, like other artists in Cuba, is on the honor system: he makes a declaration of the personal income that he has earned and he pays taxes, deducting all travel and costs.

The Bordons, too, complain about the scarcity of art supplies. On a coffee table, Yamile Pardo Menen has spread out her latest work, paintings done on fabric swatches, a resourceful use of a recycled material. Their son Pablo, twenty-three, a photographer now in his first year at ISA, would love to travel to the States. His black and white photographs, priced between $600 and $700, hang in a small back room. “A lot of Cuban artists leave Cuba and build a name outside and then come back,” he said. “How do they do it? Who knows? Perhaps they work in Starbucks!”

All day long, tourists stream into Taller Experimental de Grafica, a state-supported institution off Cathedral Square that was founded in the middle of the Missile Crisis in 1962. Since its founding, the workshop has been under the direction of the Provincial Ministry of Culture, but director Octavio Irving Hernandez says that they are about to “move to a new model.” Historically, the state spent a great deal on the workshop: they owned the building and paid the water and power bills, and the staff’s salaries. But there was never enough money for materials.

“When we needed materials, we would give the state (the Cuban Cultural Goods Fund) the artists’ work as an exchange. They would sell the prints in state galleries and in fairs outside in Cuba and the money that we earned (we had no bank account) would be used to buy materials.”

The new model calls for changing the status of the institution by leaving the Provincial Ministry and moving to the National Council of Visual Art, where Irving will soon be the Advisor/President. Such a change means that Taller Grafica will receive four times the amount from the state and, most importantly, will have its own sub-account in the bank.

Presently, Taller Grafica provides services to artists free. Some bring their own materials, and come for the help provided by a printmaker. When they produce an edition of thirteen, ten copies go to the artist to sell and three to the workshop. Other artists are invited to work at the space and materials are provided. In these cases, half of the sales from the edition go to the artist and half to the workshop. In addition to selling pieces belonging to members and artists who print there, Taller also sells the work of other artists.

This is in marked contrast to the high-end art market, where all of the sales are to non-Cubans.

In January, Dania Fleites’ “Isla” (Island), a hand with different fingers, was hanging in Taller’s front gallery. Fleite’s spoke of the meaning behind her hand-colored etching. She chose the title because the condition of every Cuban is marked by this peculiarity, and because every man and woman is an island, an individual life that intertwines. In the print, Fleites has drawn over the etching with spider webs referring to the suspended and repressed relationship between Cuba and the United States. Nearby hangs “In the Backyard of Sharks,” an etching by Alejandro R. Sainz Alfonso, who has been a Taller member for twenty years. It shows a man in a diving suit, mowing grass, with a sea of sharks nearby. A one-man show by Sainz is scheduled for later this year.

Behind the gallery, in the workshop, artists were at work carving woodcuts for a Pinocchio exhibit. Each artist has been assigned to illustrate one chapter. The plan is to publish a children’s book, if they can find a publishing house for it.

Works sell at a wide price range—from a mere 20 CUCS for a small print to 5,000 CUCS for work by the renowned graphic artist Julio Cesar Pena. Irving is encouraged by a shift, however modest, in his art buyers. “Years ago,” he said, “we were only dependent on foreigners. What’s new now is that there are many more foreigners, but also a national group of collectors, a middle class that is growing in the country. People who are self-employed and who are supporting Cuban art.” This is in marked contrast to the high-end art market, where all of the sales are to non-Cubans.

Then, to emphasize his point, Irving added: “It’s not only my opinion. Everywhere, the middle class is investing in art in Cuba.”