Like many of the artifacts of its age, the 1923 silent film Souls for Sale tells two stories. The first is somewhat ordinary, a preacher’s daughter leaving behind a seemingly picturesque small-town romance to set out for a life on her own. (And because this was old Hollywood, that escape involves jealousy, uncovered secrets, and murder.) The second, which likely provided a stronger pull than the love story, is of the thrill of cinema itself. The heroine, played by Eleanor Boardman, steps off a westbound train onto a location shoot in the California desert and spends the rest of the film climbing the ropes of the movie industry. The narrative soon becomes a series of behind-the-curtain glimpses at the studios and backlots of films in production at the time; there are cameos by Charlie Chaplin and King Vidor, a well-known director who would become Boardman’s real-life husband. The appeal of the movie was the appeal of Hollywood and, perhaps more than anything else, a celebration of the idea that the movie business was open to regular folks from small-town America if they had enough ambition and grit, and just a little bit of luck.

All known prints were thought to have been lost or destroyed, but the film was rediscovered in 2006. A Wikipedia page sprouted up, first as a stub—a kind of pre-article—created by a teenage hobbyist writing under the pseudonym “Volatile,” who described his affection for Wikipedia as a tool for procrastination. The stub was expanded by a Russian-Canadian composer whose interests, according to the trail he left across the site’s pages, also included cold weather, Isaac Asimov, and the history of Soviet and Russian animation. Another user emerged briefly from a deep involvement in baseball history to correct the title of a film referenced in the movie.

With the DVD release of Souls for Sale, in 2009, reviews by credentialed writers began to appear. The Wikipedia entry expanded. One user visited the page after writing a series of entertaining entries elsewhere on Wikipedia—about Gotham City and Charles Bukowski, for example. He—or she, as the visitor left no identifying remarks—added an entry for “turtle” on the Wikipedia page for “Inherently Funny Word.” There was a lengthy and thoughtful addition on the early career of folk-musician John Prine. This user uploaded a comprehensive list of shooting locations for the Batman films, with the conclusion, quickly redacted by other editors, that “based on the films, Chicago seems to have the best claim as Gotham City.” On the Souls for Sale page, this user added a link to a review of the film by Roger Ebert.

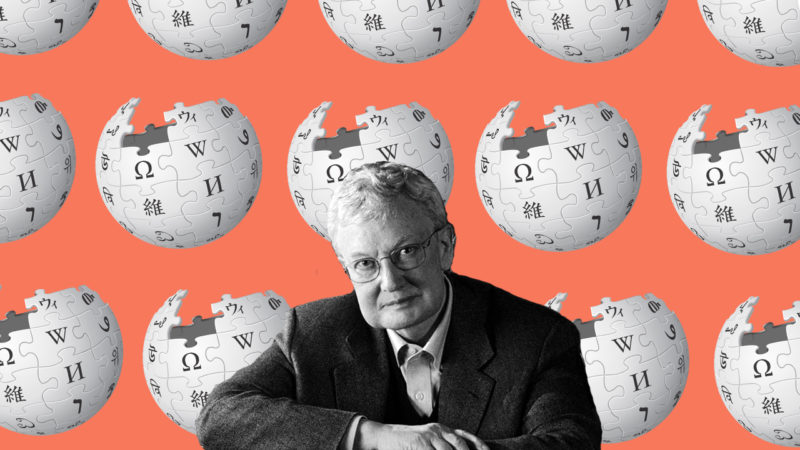

It’s often assumed that Wikipedia’s strength comes not just from its ambition, but from its openness—those anonymous fingers on keyboards could belong to anyone. But it’s an openness with limits. By 2009, articles on English-language Wikipedia alone underwent more than five million changes per month, and an institutional bureaucracy began to fall into place to keep it from sprawling into the disorganization of other online message boards. A growing number of bots—simple algorithms targeting specific violations—stopped suspicious edits before they went live or tagged them for further review. Neutrality, one of the encyclopedia’s founding principles, was a constant bugbear; one of the site’s pillars states that “editors’ personal experiences, interpretations, or opinions do not belong,” and at least one bot targeted users who added links to non-Wikipedia pages that nonetheless contained their Wikipedia username, marking these edits as a “possible conflict of interest.” This is precisely what happened to the link, on the Souls for Sale page, to the Roger Ebert review. A Wikipedia bot marked the edit, suggesting that its author was the very same Roger Ebert who had reviewed the film, and so many others, for the Chicago Sun-Times. The bot detected a thinly veiled act of promotion on the part of this user, whose Wikipedia handle was Rebert.

The bot’s accusation, of course, couldn’t be proven; Twitter and Facebook have strings of fake Roger Ebert profiles. The bot tagged the page for review by the administrators who comb through the encyclopedia’s change logs to question revisions that do not meet Wikipedia standards, sometimes undoing edits and often blocking or banning repeat offenders. The edit ended up staying, but so did the accusation. Rebert has not made any contributions to Wikipedia since.

Roger Ebert is the only critic with a star on the Hollywood Walk of Fame. By the early 2000s, he had been reviewing films for more than thirty years, and his reviews were syndicated to two hundred newspapers worldwide. He was the first film critic to win the Pulitzer Prize. With Gene Siskel, he helped bring film reviewing to television and shaped not only the next generation of critics, but also the popular idea of what a film critic could be. When he died, in 2013, he was eulogized by President Obama—very likely the first comment by a sitting president memorializing a film critic. There’s a convincing argument that the way Roger Ebert thought about movies has touched everyone who expresses their opinion of a screening with the direction of their thumb.

When Ebert wanted to broadcast his thoughts about a movie, or start a conversation about the merits of his hometown, he had as large a forum as any critic, or even any filmmaker, of his generation. Did he also spend his spare time fiddling away in the shadows, making corrections and adding trivial details on some of the least-trafficked pages of this distant corner of the Internet?

When Roger Ebert was asked on his blog—where he was famously responsive—which actor he would like to play him in a film that had been swinging in and out of preproduction, he suggested Philip Seymour Hoffman or Jack Black, either of whom could easily be imagined stepping through the door of a buzzy sixties Chicago newsroom. Ebert began reviewing films for the Chicago Sun-Times in 1967, before he was even twenty-five years old, and with barely any experience as a film critic. Yet he brought to the job the supreme self-confidence he’d developed by working in journalism since he was fifteen, when he got an offer to cover sports for his hometown newspaper, the Urbana News-Gazette. In his autobiography, Life Itself, Ebert describes himself at the time as “tactless, egotistical, merciless, and a showboat,” a blue-collar writer loyal to romantic and macho ideas of newspaper lore. The reviewing job was a step away from his ambition to become a political columnist and, eventually, “a great and respected novelist.” But Ebert fell deep into film. By the middle of his career, he said, he watched five hundred movies a year, reviewing half of them.

Reminiscing in interviews, very aware of his own myth, Ebert would point out how, at the time he started writing reviews, they were typically banged out under shared pseudonyms like “Mae Tinee”—even major newspapers didn’t think movies were important enough to have a full-time reviewer on staff. Still, Ebert got to work, writing in the first person from the start, applying his personality to Pauline Kael-inspired pieces—chatty, felt impressions from the cinema that could easily freewheel into theory or history without dropping his straight-speaking prose style. In his autobiography, he recalls Kael telling him her technique: “I go into the movie. I watch it. I ask what happened to me.” It could equally have been Ebert’s.

I first heard a rumor that Roger Ebert had edited Wikipedia entries in 2014, during a conference in London. I had begun a series of interviews with Wikipedians and hoped to find well-known writers who also made Wikipedia edits. There were many, I was told, but there was a catch: other than the novelist Nicholson Baker, who chronicled a brief mania for bolstering minor Wikipedia entries for The New York Review of Books in 2008, they edited only their own pages. Scholars and experts who were little known outside their fields, I’d come across many of those—but no one knew of a famous writer with a Wikipedia habit aimed at adding to general knowledge.

The possible exception, a video producer at the Wikimedia Foundation had heard, was Roger Ebert. I knew Ebert as an often-quoted film critic, but not as a pop phenomenon. In Australia, where I’d grown up, we had our own syndicated version of At the Movies, which replaced Ebert and Gene Siskel with two mild-mannered Australian hosts who were also known simply by their first names, Margaret and David. I began to dig into Ebert’s history as a writer and a possible Wikipedian.

Behind each Wikipedia entry is an annotated public log of the changes to its history, available to anyone who wants to look. Rebert had left a diverse record of contributions, gravitating around film and Chicagoland trivia. They were the sorts of edits the real Roger Ebert might make. Rebert’s addition, for example, to the page on musician John Prine: “In the late 1960s, whilst Prine was still delivering mail in Maywood, Illinois, he began to sing on open mike evenings.” It’s written in a style that seems a closer fit with Ebert’s straight-talking reviewer voice than the typical dry encyclopedia entry. And, further down the page: “Chicago Sun-Times movie critic Roger Ebert heard him there and wrote the first review Prine ever received, calling him a great songwriter.”

Wikipedia is not exactly a public habit, but Ebert was a public critic, and surely one of the many people who conversed with him must have gotten onto the topic. I began to make a list of people who might speak to me about working with Roger Ebert, especially those who had collaborated with him on any sort of digital project. If they could confirm that Rebert was Ebert, they might be able to explain why Ebert would choose to add to a Web page open to anyone, after he had passed through so many doors open to hardly anyone else, and what he might have foreseen about the mixed terrain that critics navigate today, so long after reviews first moved from printed page to tube to digital screen.

By the time Rebert was editing entries on Wikipedia, Ebert already had a long history of digital experimentation. When he traveled to the Cannes Film Festival in 1989, he brought a fifteen-pound portable computer called the TeleRam Portabubble. The suitcase-sized machine gave him the ability to publish with speed during the festival—not standard at the time—and made a spectacle for other journalists who would come into Ebert’s hotel room and gawk. Ebert had been a member of CompuServe since 1983 —“when it had fewer numbers than I currently have on Twitter,” he wrote, looking back, three decades later—and began syndicating his reviews there in 1990, requesting that they also create a forum for him to be able to respond to his readers. By 1994, he was in CD-ROM format with Microsoft’s Cinemania, and by 1998 he began migrating his corpus of writings to a website he had created, rogerebert.com. It wasn’t until four years later that the site finally launched, underwritten by Ebert’s publisher, the Chicago Sun-Times, which was wary of losing Ebert’s considerable Web traffic. He never guarded his email address at rogerebert.com, which was the same handle as the mysterious Wikipedia editor: Rebert.

“I’m not at all surprised,” A.O. Scott, co-chief film critic at the New York Times, told me when I shared my suspicion that Ebert might have edited Wikipedia. Ebert “was, first of all, a prolific, you might say compulsive writer, famous for the speed with which he could turn out copy, almost at the rate of speech. A clean six-hundred-word review in thirty minutes, sometimes at the rate of five or six a day. I’ve known a few other people like this, and sometimes wished I was one, but what was unusual about Roger was that, unlike many graphomaniacs who write to relieve themselves of the noise in their heads, he wrote almost entirely as an act of communication.”

Writing for a local paper, and then squabbling with his readers on the street, offered Ebert one kind of intimacy; television offered another. “It brings you into people’s living rooms, even into their bedrooms,” Scott said, “and the success of his show with Gene Siskel was based partly on the appeal of hanging out with those guys.”

Dana Stevens, the movie critic at Slate, remembers being touched by the populism of Ebert’s criticism since she was a child. She wrote him a fan letter when she was “somewhere between eleven and thirteen” years old, asking how to become a film critic. And he wrote back: “go to all the good movies you can, and write-write-write for anyplace that will print your stuff.”

“It seems to me like you can draw a straight line from the daily newspaperman Ebert started out as to the TV personality and, eventually, the powerful online presence he became. All three of those modes of criticism were about connecting with the maximum number of people possible to communicate his ideas about movies and, eventually, life,” she says. Though “it does seem like a mind like Ebert’s would be a little underemployed making edits to Wikipedia.”

In 2002, following a cancer diagnosis, Ebert had the first of a series of surgeries that eventually resulted in the loss of his jaw and his ability to speak “At first, for a long time, I wrote messages in notebooks,” he would later recall. “Then I tried typing words on my laptop and using its built-in voice. This was faster, and nobody had to try to read my handwriting. I tried out various computer voices that were available online, and for several months I had a British accent,” which his wife, Chaz, affectionately called “Sir Lawrence.” “There are all sorts of HTML codes you can use to control the timing and inflection of computer voices, and I’ve experimented with them. For me, they share a fundamental problem: they’re too slow.”

Steve James, a filmmaker whose work Ebert championed, approached him about making a documentary covering this period, which would turn out to be the last few months of Ebert’s life. Following the removal of his jaw, the lower half of Ebert’s face was left structureless. One journalist described it as “hanging loosely like a drawn curtain, and behind his chin there was a hole the size of a plum.” In James’s film, Ebert sits in a chair with a Mac almost built into his lap. “When you look at his website and you look at all the comments, if you start reading down on one of the more talked-about blog entries or reviews, deep down in the comments, hundreds of comments,” James said, “you’ll see him responding to people.

“He wasn’t just a guy who wanted his opinion to be heard and that’s that. He really loved the back and forth, he loved the engagement of ideas around movies. But the Internet made possible that kind of immediate direct exchange of ideas.

“There was a time when the studios did not consider a critic who was only on the Internet, and not affiliated with a print publication, a real critic,” James told me. “They barred them from screenings.” Ebert “went to bat for them, basically saying that’s ridiculous and they need to be allowed into screenings like everyone else because this is the future of film criticism. So Roger was part of extending the reach of film criticism to a much broader audience through television, and then when he went to the Internet he did it again.”

By the time Ebert took to the Web, Wikipedia had become one of the ways of reaching that audience. “The Internet was changing how people got access to reviews,” said Jim Emerson, a critic who helped Ebert build rogerebert.com. Craig Newmark, the founder of Craigslist and a longtime Wikipedia donor, has called it a “first draft of history,” echoing what had been said for so long about the daily press. Online, Ebert found the inclusive, participatory criticism he loved, and had experienced through the paper, chatting with Sun-Times readers, but he also found that it changed how people discovered movies, and the conversations about them. “When you Google something,” Emerson said, “Wikipedia usually shows up near the top of the results. Roger, as someone who spent so much time online, was well aware of its influence.”

The Internet also gave Ebert a way to navigate the world of his illness. He didn’t begin writing a blog until after his first hospitalization. Before long, “my blog became my voice, my outlet, my ‘social media’ in a way I couldn’t have dreamed of,” he would later write. “Into it I poured my regrets, desires, and memories. Some days I became possessed.

“It is human nature to look at someone like me and assume I have lost some of my marbles. People talk loudly and slowly to me. Sometimes they assume I am deaf. There are people who don’t want to make eye contact.” He called writing on the Internet “a lifesaver.”

“Roger always was a guy who had this ability to cherish both the tradition of film and film watching,” James, the documentary filmmaker, told me. “He says in the movie that there’s nothing better than being in a big movie theater with a thousand people and a ten-story-high screen, laughing in unison. He loved that, but at the same time, one of the things that made him so interesting and distinctive is that he also understood that for the lifeblood of cinema, and the lifeblood of cinema criticism, you needed to embrace all ways in which people can come to a film.” But James couldn’t remember ever hearing Ebert speak about editing Wikipedia.

I took a closer look at Roger Ebert’s late reviews and essays, which are filled with phrases like “thanks to Wikipedia,” “Wikipedia splendidly explains,” and “my pals at Wikipedia filled in some of the blanks for me.” I reached out to Matt Zoller Seitz, a critic and the current editor in chief of rogerebert.com, which continues to publish reviews. “Finding out that Roger was quietly editing Wikipedia entries fits the mental image I have of him,” Seitz said. “Roger understood the Internet long before a lot of critics of his celebrity understood it, so it follows that he would grasp what Wikipedia was: essentially the Great Library of Alexandria, but online, and constantly changing and evolving. He wanted to be a part of that, clearly. And I am guessing he also understood that while a newspaper or magazine or personal website might not be around forever, something like Wikipedia, as a collective, might have a somewhat better shot.” Asked if he could confirm Ebert’s Wikipedia habit, though, Seitz, could only give his best guess. “At this point it’s probably too late.”

“When I’m on the forum,” Ebert said about his early days on CompuServe, to an interviewer from Wired, “I get instant chat messages that say, ‘Is this really Roger Ebert?’ If I answer ‘Yes,’ they write back, ‘No, it’s not.’ If I answer ‘No,’ they write back, ‘Yes, it is.’ If I write, ‘The answer to that question cannot logically be settled via computer,’ they write back, ‘Gee, I was just trying to be friendly.’”

Almost all of the filmmakers and critics I asked about Roger Ebert mentioned his early curiosity about technology, his openness to ways of transmitting a love of the movies. A few suggested that the anonymity Wikipedia offered may have been attractive to him later in his career. Ebert “didn’t only write to be visible and influential. He wrote because he enjoyed it and because it made him less lonely,” A.O. Scott told me. “And Wikipedia, I’m guessing, offered a chance to write about whatever he felt like. No one could say, ‘Who cares what Roger Ebert thinks about that?’”

Ebert’s colleagues shared a lot of hunches and best guesses; it would make sense that Ebert would, but no one could tell me that he did. He hadn’t spoken about it with any of them. It was starting to seem like, if Ebert edited Wikipedia, it was his private habit. But one or two, cautiously, wondered if there might be one place I hadn’t looked: Was I going to try to speak to Chaz?

Roger Ebert and Chaz Hammelsmith met in 1989 and married in 1992, when Ebert was fifty. “How can I begin to tell you about Chaz?” Ebert writes in his autobiography. “She fills my horizon, she is the great fact of my life, she saved me from the fate of living out my life alone, which is where I seemed to be heading.” Their relationship is the heart of Steve James’s film. “She didn’t seem to be a ‘date,’ but an equal,” Ebert recalled thinking of their early courtship. Of their love letters: “As a newspaperman, I observed that she never, ever, made a copy-reading error.” It was Chaz, James told me, who convinced Ebert to start tweeting. “Originally he didn’t get the whole idea of Twitter. She had to encourage him.”

Before long Ebert asked Chaz to leave her job as a civil-rights attorney and focus on their combined enterprises. “I’ve never understood business,” Ebert wrote, “and have no patience with business meetings or legal details. I had a weakness for signing things just to make them go away. She observed this, and defended me. It was a partnership.” Chaz remains in charge of a raft of projects that continue after his death; she is the publisher of rogerebert.com, which has a masthead of dozens of critics; there is the Ebertfest, Ebert fellowships and scholarships, an upcoming Ebert museum.

“If my cancer had come, and Chaz had not been there with me, I can imagine a descent into a lonely decrepitude,” Ebert wrote. “She was there every day for two years, visiting me in the hospital whether I knew it or not, becoming expert on my problems and medications, researching possibilities, asking questions, making calls, even giving little Christmas and Valentine’s Day baskets to my nurses, who she knew by name.”

Steve James had become close with Chaz while making Life Itself, and offered to put me in touch. Chaz was in Los Angeles, preparing for the Oscars, but she found some time. I reached her by Skype and told her what I had found: Ebert referencing his Wikipedia use in reviews, Rebert arguing that Chicago has the strongest claim as a real-life Gotham City, based on filming locations of the “Batman” movies. Rebert noting that a particular review of a film on intelligent design, one of Ebert’s many obsessions, drew more than a thousand comments online.

“Well, he would say sometimes that ‘Oh I see something that needs to be changed’ or ‘I see something that needs to be added,’” Chaz told me. “He would say things like that to me.”

But couldn’t he have said that, and never made any changes?

“He wouldn’t just say, ‘I’m going to edit that on Wikipedia,’” she said. “But there are things that I’ve read there that I know are things that he wrote. R. Ebert—Rebert, was my husband.”

Did other famous writers edit Wikipedia? If so, they would remain secret to me, as would their motivations—whether they were contributing to the world’s general knowledge or search-engine-optimizing themselves into history. From the initial tip, I half-expected to come across a cabal of them, driven to the site by a culture industry blurring the line between promotion and critique. Wesley Morris, a critic at the New York Times, spoke of the Internet as a “convergence of users and so-called experts, democratizing in the sense that it’s provided access to people who haven’t had a voice,” but at the expense of traditional ideas of expertise and authority. A.O. Scott saw criticism online flourishing as an activity, but not as a paying job—more criticism, fewer critics.

What I found, when I began to ask why someone so famous might be editing Wikipedia, was a portrait of one person at a particular moment in life. For Ebert, Wikipedia was a laboratory for the back-and-forth criticism, and the sense of human connection, that he searched for across formats, in and out of movie theaters; the site was a refuge that offered what had drawn him to criticism in the first place. It made sense that Rebert’s edits synched up, chronologically, with Ebert’s hospital days.

“I really think my husband is a meme,” Chaz told me. “That’s the way I think of him. Usually you think a meme as one kind of idea or movement that takes hold—it can be in different parts of the country or different parts of the world, sometimes seemingly in isolation and without collaboration. But when I say Roger was a meme I mean it in a way that whoever is looking at him, he’s kaleidoscopic. When you look one way, he’s this critic; when you look the other way, he’s this political animal, but he always has all of these things going on at the same time. It’s really interesting when I’m trying to read something where someone is trying to explain what Roger is to them, and they’re so, so sure that they have it all figured out, and I say that’s just a small part of it. Whatever he is means something different to different groups or at different times, and I like that, and he would have loved that. He would have loved that.”