The Arabian Nights (or the Thousand and One Nights, or the Arabian Nights Entertainments—there are so many versions) constitute, in Marina Warner’s words, “a polyvocal anthology of world myths, fables, and fairy tales.” The antecedents of these Arab-Islamic texts are Quranic, Biblical, Indian, Persian, Mesopotamian, Greek, Turkish, and Egyptian. In them, oral and written traditions, poetry and prose, demotic folk tales and courtly high culture mutate and interpenetrate. In their long lifetime the Nights have influenced, amongst many others, Flaubert, Wilde, Marquez, Mahfouz, Elias Khoury, Douglas Fairbanks, and the Ballets Russes.

The frame story, in which Shahrazad saves her life by telling King Shahryar tall tales, is only one such ransom. More than simple entertainment, then: throughout these stories within stories, and stories about stories, and stories metamorphosing like viruses, endlessly generative, narrative even claims for itself the power to defer death.

Although oral versions of the Nights had long percolated through Europe (elements turning up in Chaucer, Ariosto, Dante, Shakespeare), the tales were established in the mainstream of European popular and literary culture with Galland’s early 18th century French translation. Galland purged the eroticism and homosexuality, added tales from the dictation of a Lebanese friend, and perhaps invented the two best-known and seemingly most “Arabian” tales of all: Aladdin and the Magic Lamp and Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves.

Warner quotes Jorge Luis Borges (a guiding spirit in her book) approving the belle infidele approach to translation. “I think that the reader should enrich what he is reading. He should misunderstand the text; he should change it into something else.”

It’s this changing aspect of the Nights as a time-travelling, trans-civilisational cooperation which fascinates Warner. She sees in it “a unique key to the imaginary processes that govern the symbolism of magic, foreignness and mysterious power in modern culture.”

Stranger Magic is a post-Saidean endeavor to uncover “a neglected story of reciprocity and exchange.” One of Warner’s central intentions is to show that while Christendom and Islam were politically and religiously in a permanent state of hot or cold war, science, philosophy and art recognized no frontiers. This openness closed somewhat, however, from the Enlightenment on, when Europe sealed magic off from science, imagination from reason, and also east from west, black from white.

The Enlightenment, of course, was the point at which the Nights was translated to such rapturous European reception, and not by accident. The “home-grown practice of, and belief in, magic was set aside to be replaced by foreign magic—stranger magic, much easier to disown, or otherwise hold in intellectual or political quarantine.”

So to the orientalisms of Lane and Burton’s English translations, which not only presented the medieval fantastic as a documentary resource for understanding the ‘unchanging’ and now colonially subjected Arab culture of the 19th Century, but also projected onto the exotic foreign screen fantasies and fears which would have been taboo in a domestic context. Burton famously resexualised the Tales with his own copious notes on the east’s supposed perversions and genital enormities.

During the Enlightenment, black magic became inevitably dark skinned; necromancy (to employ two words investigated by Warner) became inseparable from nigromancy.

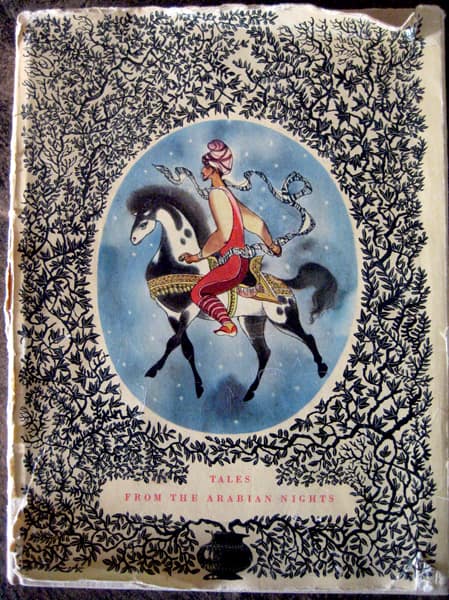

Stranger Magic is an enormous work, 436 densely erudite and eclectic pages plus almost another hundred of glossaries and notes. In its relentless connecting up of diverse stories, from the Inferno to His Dark Materials, it’s reminiscent of Christopher Booker’s brick-sized Seven Basic Plots. Warner’s chapters are allocated into five parts, are beautifully illustrated, and interspersed by fifteen Tales concisely retold.

Part one focuses on the jinn—whose special narrative benefit is that, like the Greek gods, they can behave badly, capriciously, illogically—and also on the figure of Solomon, a master of the jinn in his Islamic version, here located in the white wizard tradition somewhere between Gilgamesh, Merlin, Prospero, and Gandalf. One of the book’s many delightful discoveries enters the discussion here—a 14th Century Syrian treatise on the legal status of jinn-human marriages.

The second part attends to the Arab and European habit of attributing foreignness to evil magicians. The dark enchanters come from dark places (Africa and India) and profess dark (pre-Islamic) faiths. “The Orient in the Arabian Nights,” Warner writes, “has its own Orient.” During the Enlightenment, black magic became inevitably dark skinned; necromancy (to employ two words investigated by Warner) became inseparable from nigromancy.

Part three examines how the stories “test the border between persons and things” and how severed heads which speak, books that kill and carpets which fly link to our 21st century objects, not only cinema’s animated objects but also the prosthetic goods of everyday life, the designer labels, gadgets and vehicles by which we project and define our personalities.

In this section, Warner moves from considering the derivations and meanings of the word ‘talisman’ to reflect on her own attachment to talismans in her Catholic girlhood (her personal appearances in the book are apt, easing the academic tone) before launching into a fascinating discussion of the talismanic properties of paper money.

The fourth part reflects on writerly responses to the Nights, including Voltaire’s contes, Goethe’s East-West Divan, and (a great chapter) the neglected Gothic novelist and Islamophile William Beckford.

The fifth deals with flight, cinema, shadow play, and Freud. Warner describes the Hampstead cave of wonders which was the final consulting room, “a darkling mirror of the furnishings of his mind”, and the iconic analytical couch draped in oriental cushions and rugs. Specifically a Ghashgha’i tribal rug, which leads by glorious digression to Mohsen Makhmalbaf’s rug-themed Iranian film Gabbeh, and to a reminder that oriental rugs, the Nights and psychoanalysis are all narrative forms.

Stranger Magic is a labor of love, an academic work which often reads like a fireside conversation. It’s encyclopediac, a book to be savored in slices, yet (inevitably) it’s easy to think of further potential topics—giants, for instance, or dervishes, or magical realism from the Arabs via La Mancha to the Latin American Boom. But Warner’s conclusion reminds us of her organising principle: the uses of enchantment to open new possibilities of thought and sympathy, indeed the necessity of magic, especially in a self-consciously “rational” and secular world.

By arrangement with Qunfuz.com. Originally published in the Guardian.