By Robert Reich

By arrangement with Robert Reich

Forbes Magazine, which calls itself the “capitalist tool,” seems to have a penchant for publishing right-wing diatribes posing as serious economic analyses. The latest is by Paul Roderick Gregory, who accuses me of “false facts and false theories” in a recent piece I wrote about why high wages are good for the economy.

The answer is simple: Ours was a land of unbounded natural resources that were exploited without regard to consequences for the environment.

If I’m correct, Gregory asks, how could it possibly be that America become world’s richest and most powerful economy in late nineteenth century, when the typical worker was earning peanuts?

Gregory claims to be an economic historian but he doesn’t seem to know American history. The answer is simple: Ours was a land of unbounded natural resources that were exploited without regard to consequences for the environment. We also found it relatively easy to copy the industrial advances of England and Germany, and erected a protective tariff so that our manufacturers didn’t have to compete directly with them. A giant wave of immigrants came to our shores, willing and eager to work for very little. And our largest industries—oil, railroads, steel—were monopolies or oligopolies that generated huge profits for their owners while skewering their customers. The result of all this was fat corporate profits, some of which were reinvested. Hence, the economy grew.

When most of the gains of economic growth go to the top, the vast majority no longer has the purchasing power they need to buy what the economy is capable of producing.

That was a recipe for economic growth, but not a recipe any sane person would want repeated even if that were possible. The late nineteenth century is hardly a model for twenty-first century American capitalism. I seriously doubt Gregory wants us to go back to an era of urban squalor, robber barons, corrupt city machines, unsafe factories, and poisonous food and drugs.

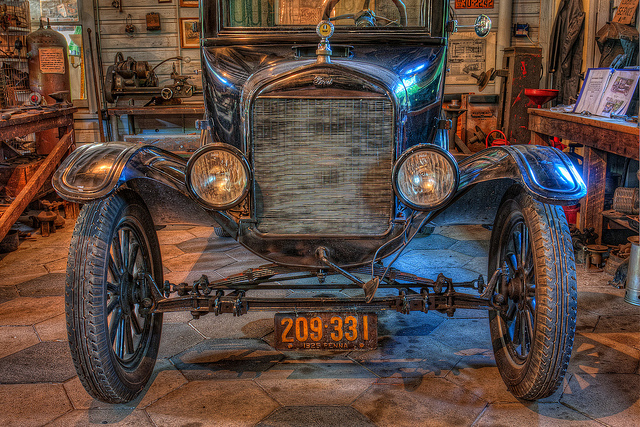

Gregory then criticizes me for suggesting that Henry Ford benefited financially by increasing the wages of his workers, who could then afford to purchase Model T’s. Gregory says Ford increased the wages of his workers because, in Gregory’s words, “Ford could afford” to pay his auto workers more, given the enormous productivity increases generated by his assembly lines.

Of course Ford could afford it; he couldn’t have done paid them more otherwise. But the fact Ford could afford to pay his workers more doesn’t explain why he chose to do so. As any self-respecting Forbes’ capitalist tool knows, just because a corporation can afford to pay its workers more, doesn’t mean it will do so. Ford paid his workers more because he found it in his economic interest to do so.

Gregory goes on to say that total wages rose sharply from 1915 to the Great Depression, but he completely misses (or ignores) my point. Income inequality widened dramatically in the 1920s. It reached a peak in 1928, when the top 1 percent took home over 23 percent of total income—just as inequality rose in the years leading up to the Great Recession, culminating in 2007, when the top 1 percent again took home over 23 percent of total income. (These data come from the pioneering work of professors Immanuel Saez and Thomas Piketty.)

When most of the economic gains go to the top, the only way the middle class can keep up is to borrow.

It is no coincidence that 1928 and 2007 marked the high-water points of income inequality, and that the bottom fell out the following years. When most of the gains of economic growth go to the top, the vast majority no longer has the purchasing power they need to buy what the economy is capable of producing.

It’s also no coincidence that household debt more than doubled in the 1920s, from 15 percent of GDP in 1920 to 32 percent of GDP in 1929—just as consumer debt mushroomed eighty year later leading up to the crash of 2008. When most of the economic gains go to the top, the only way the middle class can keep up is to borrow. But as we learned in 1929 and then again in 2008, there’s a limit to how much can be borrowed. Eventually debt balloons burst, and millions of innocent people go bust.

Gregory then looks to the present day and finds nothing at all remarkable or troublesome about corporate profits soaring while the median wage drops, adjusted for inflation. He says it happens in every upturn—corporate profits always rise before worker compensation rises.

Where has this man been living for the past several business cycles? Does he not know that the median wage has barely increased for three decades, and that it is now 5 percent lower than it was in 2000, adjusted for inflation? Does he not have access to the fact that wages are now a lower percent of the total economy and corporate profits a higher percent than at any time in the last thirty-five years?

Gregory doesn’t like the notion of “middle-out economics” and believes that the captains of industry are the real job creators. But businesses need consumers in order to prosper and grow. Consumers in the middle class and below are the real job creators. In the United States, 70 percent of economic activity is personal consumption. Unless the vast middle class, and everyone seeking to join it, have enough money in their pockets—and share sufficiently in the gains from growth—businesses cannot possibly do well.

Like most polemicists who don’t really have arguments to support their diatribes, Gregory resorts to ad hominem attack (my arguments is, he says, a “hackneyed respires of Karl Marx;” I’m not a real economist, he says, but a lawyer who “studied a smattering of economics at Oxford,” and so on). Gregory has a history of attacking others, such as Paul Krugman (who happens to have received a Nobel Prize in economics), with the same mixture of illogic, distortion, and disdain.

Why Forbes continues to publish this sort of garbage is beyond me. Perhaps Forbes feels compelled to provide a steady diet of right-wing drivel to its readers. Why someone who holds a tenured position at a university would stoop to write this garbage is also mystifying. Maybe Forbes pays its pundits well. And as every economist knows, money can elicit the most remarkable of inventions.

Robert B. Reich, Chancellor’s Professor of Public Policy at the University of California at Berkeley, was Secretary of Labor in the Clinton administration. Time Magazine named him one of the ten most effective cabinet secretaries of the twentieth century. He has written thirteen books, including the best sellers Aftershock: The Next Economy and America’s Future and The Work of Nations: Preparing Ourselves for 21st Century Capitalism. His latest, Beyond Outrage: Expanded Edition: What has gone wrong with our economy and our democracy, and how to fix it, is now out in paperback. He is also a founding editor of the American Prospect magazine and chairman of Common Cause. His new film, “Inequality for All,” will be out September 27.