In 1933, the photographer André Friedmann arrived in Paris with a camera and little else. A Jewish refugee fleeing the growing Nazi threat in Berlin, he hoped to make a living with his Leica. While shooting a model for an assignment, Friedmann found his attention settling instead on the model’s friend Gerta Pohorylle, a Jewish refugee herself who came to Paris after having been arrested by the Nazis for her involvement in antifascist activism.

Gerta recognized the young photographer’s vast potential, and the two became friends. After a summer jaunt to the south of France, they were in love. They began to collaborate: Gerta found a job at the Alliance Photo Agency and became André’s advisor, critiquing and helping him find buyers for his work, while André taught Gerta how to take photos. In 1935, hoping to make themselves more marketable (and less obviously Jewish), they changed their names to Robert Capa and Gerda Taro. As Taro, Gerta would sell the photographs of “Robert Capa,” an elusive American who only communicated via his assistant, the humble André. A year later, at the outbreak of the Spanish Civil War—the deciding factor in whether Europe would bow to the threat of fascism—the couple recognized their chance to document history and departed for the war’s front lines.

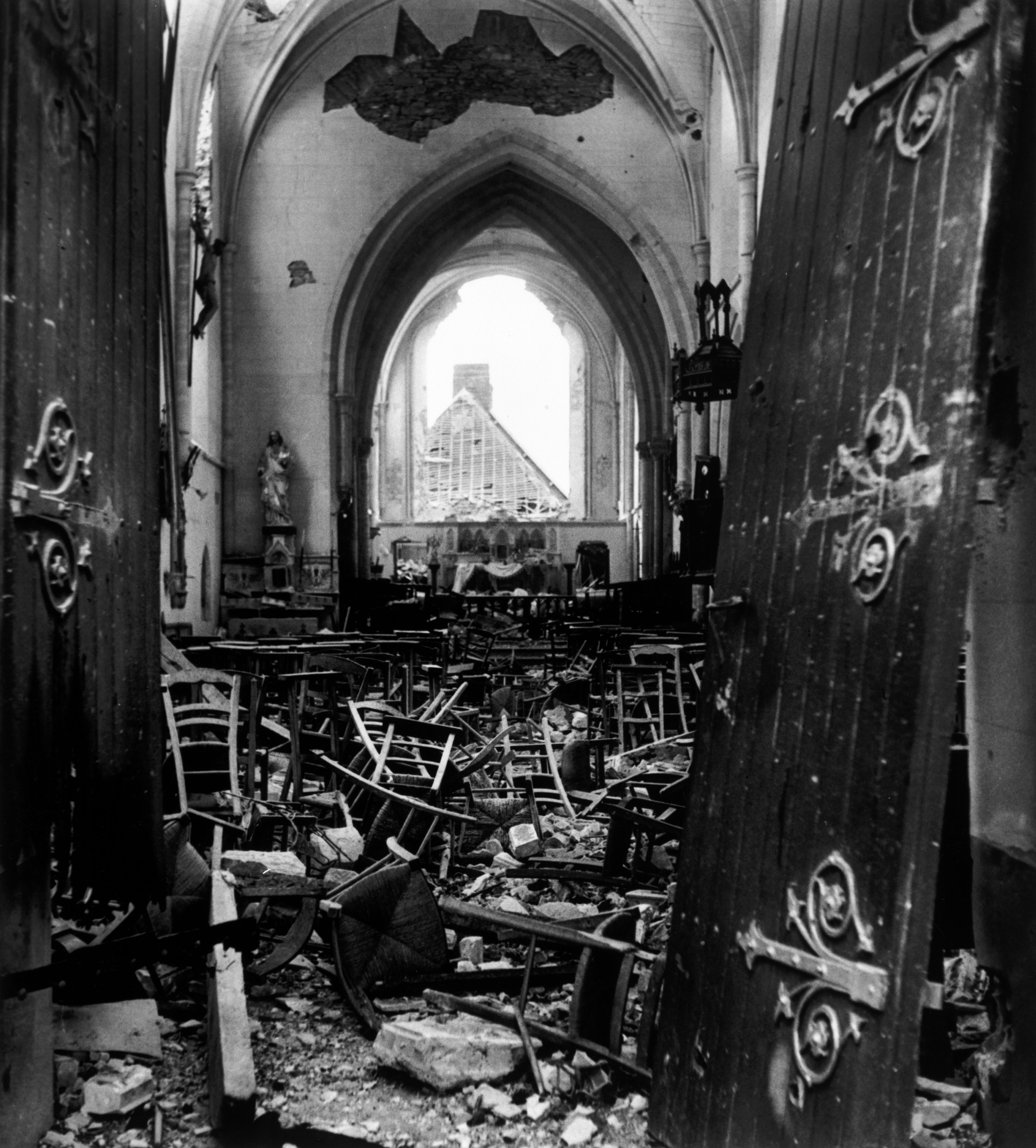

Capa and Taro’s work in Spain cemented them as war photojournalism’s reigning couple. With the development of the light, portable Leica in the 1920s and 30s, photographers could get closer to the action faster than ever before—and Capa and Taro did, taking photos of uncommon intensity and intimacy amidst rubble and noise. Their cameras were omnivorous, paying as much heed to children spooning soup as battlefield din. The couple’s good looks, charm, and ease with their subjects yielded photos unlike any ever taken in the course of war: Taro’s shot of soldiers in a rare moment of peace in a forest camp, Capa’s of a mother and child leaving their home, their lives packed into a suitcase. Their enduring work, much of which is housed in the archives of the International Center of Photography, showed war not only as it was fought, but as it was lived.

Capa and Taro traveled and worked as equals, their visions so aligned that they sometimes took the same shot. Though Taro often worked in Capa’s shadow, she cast a shadow of her own, and made a name for herself independent of her partner’s. Of the two, Capa always had the bigger name and more unmistakable eye; his maxim, “If your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough,” has guided many a photographer who followed him. For his iconic images—among them, The Fallen Soldier, picturing a soldier in the instant of death, his body accepting a bullet—the British magazine Picture Post anointed Capa “the greatest war photographer in the world” at the green age of twenty-five. But though his partnership with Taro was central to Capa’s work, she is often treated as little more than a footnote to his biography.

In Eyes of the World, just released from Henry Holt, authors Marina Budhos and Marc Aronson seek to right this imbalance. Their book traces the two photographers’ lives both as a couple and as individuals whose photos set a legendary standard for photographers of conflict. Both died as they lived, in action: Taro, who was caught in an collision while photographing the trenches at Brunete in 1937, became the first female photojournalist to lose her life on assignment; Capa, who went on to found the Magnum photo agency and photograph several more wars, died in 1954 in a landmine explosion in Vietnam. Only a few years had elapsed between their first meeting and Taro’s death. Yet in that scant time, Budhos and Aronson argue, the couple invented modern photojournalism while simultaneously inventing and encouraging each other’s approach to the craft.

Budhos and Aronson honor the couple’s vision by giving photographs as much space in the book as the text. Only by reading the textual narrative and studying the photographs alongside it can we grasp the full picture of Capa and Taro’s legacy. The photographers’ lives cannot be separated from their art, just as Capa’s story cannot be told without Taro’s.

Like Capa and Taro, Budhos and Aronson are partners in both love and work: Eyes of the World marks the second project they have completed together; the first is Sugar Changed the World, a history of the sugar trade. I met the authors in the unassuming café at the Rubin Museum of Art, where they reflected on their subjects’ intertwined lives and legacies, as well as the process of co-creation.

—Jennifer Gersten for Guernica

Guernica: You describe Robert Capa and Gerda Taro as outsiders: they were Jewish refugees who powered a freelance photography economy. How did that outsider status influence their perspective?

Marina Budhos: When they started photographing the bombardments at the beginning of the refugee crisis [in 1937], they were refugees themselves. It was so clear to me that they were inventing a language, a visual vocabulary. When Capa was photographing people who made their way up to France to be in the refugee camps, he wrote about it in the captions to his photos. His own words showed the ways he identified with these refugees. Certainly in the latter part of the war, the way Capa and Taro saw things was fused with their own identity as people who had already been uprooted and who [feared] that a larger uprooting would happen.

Marc Aronson: Jews couldn’t hold full-time jobs in Paris. Think of America now, with feelings about work being taken away by “these illegals.” It was the same feeling. But this world of freelance photography was a place where Jews could survive.

Marina Budhos: Capa and Taro were stateless, and photography is a stateless occupation. You take a photograph of a march in Paris or Toulouse, and it’s sent to an agency in Germany or England—it’s a crisscrossing. Even though there was all this anti-immigrant sentiment in France, Capa and Taro weren’t afraid to plunge into these very French situations like elections and marches. So maybe the camera became a sort of protection for them. There were Nazi sympathizers all over France at this time, and a lot of anti-Semitism. The camera allowed them to maneuver with fluidity in this society that didn’t accept them.

Guernica: How did Capa and Taro intend for their photos to be used? What sort of effect did they want their work to have?

Marina Budhos: Cynthia Young [the curator of Capa and Taro’s archive at the International Center for Photography] told us that at this time, there was one kind of technology—the bombs and fighter planes and so forth—against another: the camera. Readers in those days had never seen a war of this scale. It’s very hard to take in. By honing in on the human—what a street might look like, or what it is to have a mother and her children huddled in the subways because that’s the only safe place to be—you’re making the effects of war comprehensible. Obviously we’re experiencing this now with Syria, which is why the photo of the boy from Aleppo affects us. For most of us, it’s too hard to take in the level of bombing and destruction. The photos are what’s comprehensible.

Marc Aronson: I would change it slightly: it’s not comprehensible; it’s accessible. You may or may not be able to fully comprehend a situation, but now it’s entered your world, it’s there with you. Capa and Taro’s goal was to win hearts and minds. To convince Joe sitting at his table in St. Louis that [the war in Spain] matters to him. That was their mission.

Marina Budhos: They were very willing to let their photographs be used for propaganda purposes. They would take images of, say, Madrid being bombed, and those would be used in fundraising campaigns [by activists for war relief efforts]. At a meeting in Hollywood to raise money for the Spanish Civil War, Capa and Taro’s images were played as part of a newsreel. [The actor James] Cagney saw it, walked outside, threw up, and wrote a check that paid for an ambulance. So most certainly Capa and Taro knew their images would be used for a purpose besides the general newsmagazine.

Marc Aronson: There’s a quote often attributed to Stalin: “One death is a tragedy, a million deaths is a statistic.” I think that’s the whole point of these images.

Guernica: Was Capa, as the more famous member of the couple, dominant in their relationship? How much influence did Taro really have over his style?

Marc Aronson: We’ve thought a lot about them as a couple who collaborated as pure equals, who, in effect, created each other. Taro, probably literally, invented Robert Capa. And he taught her how to photograph without any sense of territory.

Marina Budhos: When they arrived in Barcelona, they were seeing this extraordinary equality between men and women. I think they were kind of giddy. There was so much improvisation in their lives; they were just flying by the seat of their pants. They were trying to figure out how to make a living, how to make an impact. I think that atmosphere of improvisation meant that gender roles were not particularly relevant.

Guernica: It’s notable that they never married. You speculate that maybe it’s because they thought marriage would bring the two of them down.

Marc Aronson: Taro, in the midst of war, was very flirtatious. And later in his life, Capa became the essence of a ladies’ man. Was that because he was so seared by her loss? That’s one interpretation. But maybe it’s who he would have been anyway, and she knew it.

Marina Budhos: After Taro died, there were women who wanted to marry Capa, like Ingrid Bergman. He basically said, “I’m not marriageable, given the life I lead.” That life was nomadic and unpredictable, and he could have died at any moment.

I think it’s significant that he never again chose a compadre to be on the road with. He was involved with another woman who was a photographer, but she was a fashion photographer. He had these women waiting in port, but he never again went on the road with a woman in the same way. He did hold Taro in a certain place inside of him.

Guernica: The photographer Tyler Hicks has talked about “knowing when to stop,” how a photographer needs to have an instinct about when to cease. Where were the boundaries for these photographers?

Marina Budhos:: Irme Schaber, Taro’s biographer, makes the point that [the crisis in Europe] was existential for Taro. Her own family was imperiled. And so the boundary wasn’t there; she was so fused with the cause. Today, we typically see photographers who are from one place and go photograph in an embattled situation somewhere else. But Taro is part of this fight for Europe, and perhaps it led to her lack of caution. I think there was something particular about that generation of refugees—their own history is aligned with what is convulsing in Europe. [Taro and Capa’s collaborator David Seymour, known as] Chim, lost everybody in his family. Capa actually emerged the most intact: his mother and brother were able to immigrate.

Guernica: In the book, you say that Capa and Taro were almost like children. You often refer to how young they were. In a way, they’re like ingénues: as photographers, they were never completely exposed to the dangers of war because they were never the ones aiming the pistol. How do you think that naïveté influenced their work?

Marc Aronson: It seems more adolescent to me than childlike. They had a hunger to change the world, to find an ideal and a cause—to make people care. That reminds me more of the striving adolescent who detests what’s become of the world and wants to make it right. There’s certainly some of that in the cause of Spain. One thing to remember: they had no assignment. They were just in the middle of Spain with cameras, flung into the middle of a war. They are kind of like, hey, let’s go find a battle. And there is something of that innocence in their work, although there is tremendous pain all around them.

Guernica: Capa and his compatriots created the modern magazine layout and the first professional photography agency. How do you see that influence trickling down?

Marc Aronson: Again, Cynthia Young made a great point: when Capa and Taro and Chim went around Spain, they didn’t go with the famous journalists who were there, because they didn’t want their photos to be nice documentary illustrations. They wanted to create visual narration. In our book, we wanted to retain that sense of visual narration within an unfolding textual narrative. In our view, that is something that really doesn’t exist now, that sense of visual narration flowing with text.

Marina Budhos: A lot of their spreads were not factually correct. They were playing with images for the sake of impact more than accuracy.

Marc Aronson: In a word, they weren’t “documenting.” That wasn’t their goal.

Guernica: After Taro died, did any female photographers cite her as an influence?

Marina Budhos: Taro didn’t have a very large body of work, and there really wasn’t any opportunity for her to be influential. Instead, she became more of a martyr to the cause. Her photographs haven’t really been examined until fairly recently. Some of this is because some of them weren’t identified, and we didn’t know whether they were hers or not.

Marc Aronson: I think she really got occluded. She was coerced into a communist narrative. She’s buried in Père Lachaise in Paris, with other people who are communist heroes. Taro wasn’t there to argue. She had no heirs or relatives or anything. Capa died in ’54, but he was not buried there. There was a big debate about it on the left. People were saying, “She’s been defined as this communist hero, that’s not advantageous for Capa.” And so he was buried in Westchester. As their legacies developed different narratives, the less Capa’s fame brought attention to Taro.

Guernica: It seems like Capa anticipated plenty of accusations of journalistic bias, and so he distanced himself from an affiliation that might have been controversial.

Marina Budhos: They always saw themselves as aligned with antifascism. They weren’t objective, and they knew that. But even when Capa was successful, his money situation was always a mess. So I think he wanted to be able to move freely in the world, to photograph where he wanted, wherever he needed to. For him it wasn’t ideological, as much as it was a matter of survival.

Guernica: You portray Capa and Taro’s relationship as at once romantic and professional. You also describe your marriage as having these two sides. What was your own collaboration like?

Marina Budhos: We’ve learned from writing two books that one person needs to be the driver. There’s no way I could have done this book by myself. I left certain sections for Marc to do, and together we kept discussing and amplifying and thinking through things.

Marc Aronson: I think in terms of history. For me, explanation tends to come chronologically and in terms of causes and effects and themes. Marina is a novelist and she tends to find explanation in terms of scenes, events, human dramas. It’s always a question of how to blend these approaches. When should the scenes come front and center, and the explication be added to that? And when should the thematic flow come front and center, and the human interaction or drama or scene-setting enhance that? That’s something we had to work out.

Guernica: Were you reading yourselves into the relationship you were writing about?

Marina Budhos: For sure. We would talk about it. We were having conversations about what was different about their relationship and why was it different, and what could have been going on between them.

Marc Aronson: One of the fascinating moments in the book is when Capa and Taro both took the same shot. We don’t know what they were thinking. But what we can do is invest speculatively in that moment, based on what we know about their relationship and what we know as collaborators.

Marina Budhos: There’s a lot of writing about Capa because he’s this swaggery macho guy. Taro is always treated as this sidekick. As someone who works as an equal with my husband, writing this book was a moment to offer a deeper picture of two lives. I felt like that was a way to avoid making the woman the muse in the macho guy’s story.