Cheryl Strayed and I were in a small writing-group in our twenties in Minnesota, where we were both students. Strayed was younger by five or six years, which somehow means a lot more when you are young. She was bright and beautiful. This is how I remember her. And she was already a writer, in the sense that she was sure she was never going to be anything else first.

In the early 1990s, after I had got my first teaching job and moved to Florida, I’d get an occasional postcard from Cheryl. She was a profligate writer, generous and flirtatious, offering glimpses of a life that roused my envy. There were always surprises in her letters. She had walked into a café in a strange town somewhere in Arizona, say, and standing in line was Grace Paley. If memory serves, Cheryl introduced herself and Paley bought her a slice of carrot cake. But the postcards stopped and we lost touch.

In 2004, I was in transit at Chicago’s O’Hare when I paused at the airport bookstore. There was a copy of The Best American Essays sitting on display. The first line of an essay entitled “The Love of My Life” read: “The first time I cheated on my husband, my mother had been dead for exactly one week.” This sentence sent a shiver through me. Cheryl had adopted a new last name. But there was no mistaking the voice, bold and provocative, finding on the page something like clarity, if not exactly release from pain.

The enormous success of Cheryl’s memoir, Wild, an account of her hike on the Pacific Crest Trail, has only reinforced the sense of her as a writer always going for broke to tell her stories. There seems to be a desperate urgency in the act, and, mixed with it, the unfolding of narrative magic. Wild has remained stubbornly on the New York Times bestseller list since publication over a year ago. It has been translated into thirty languages. This spectacular success has carried with it the pleasant scent of surprise that I used to associate in my youth with Cheryl’s postcards. But also present in the work now, as before, is the same hunger for experience and truth.

When Cheryl came to Vassar College to speak in front of an audience in late April, we hadn’t seen each other for more than twenty years. I wanted her to give me clues about what we were then, and what she had become now.

—Amitava Kumar for Guernica

Guernica: Wild has been celebrated for its honesty, and Tiny Beautiful Things for the beauty of its compassion. But what I also very much admire in your writing is that it works on a variety of levels. Not many writers have it; we only write for our narrow enclaves. But you talk to everybody.

Cheryl Strayed: That’s a kind thing for you to say. I didn’t grow up in an educated household and I didn’t know any writers as a kid. My brother—my dear brother, who I write about in Wild—doesn’t even have a GED. He’s a high school dropout. Pretty early on in my writing career I realized that I never want to write something that he couldn’t read, that wasn’t accessible to him. That doesn’t mean he’s not intelligent—he’s a very intelligent person—but I didn’t want to write something that you have to have an advanced degree to understand. I wanted to write intelligent stories, using intelligent language, that was accessible to the uneducated as well.

Guernica: I said to my students: I want you to take Cheryl very seriously, because when I first knew her, she was the same age as you are at the moment. She was in her early twenties.

Cheryl Strayed: I was twenty-two, a senior in college.

I was basically the same person when I began my hike as I was at the end.

Guernica: What is the difference between the person you were then and the person you are now? How has writing been a part of that change?

Cheryl Strayed: All of us, as we mature and grow up—if we’re doing life right—we evolve. One of the things in Wild—and of course Wild just tells a slice of my life, it ends a couple days before my twenty-seventhth birthday—that I really wanted to write about is how we transform ourselves, how change looks in real, actual lives. I think in some ways Wild works against the transformation narrative that we see so often—what I’m just going to go ahead and call “Hollywood”—and that is, somebody starts off, and they’re this terrible sort of Charles Manson–like person, and then they go through their journey and at the end they’re the Buddha. [laughter] I was basically the same person when I began my hike as I was at the end.

If you knew me then, as you did, Amitava, you wouldn’t say I was terribly different after the hike than I was before. The changes that this radically transformative experience brought about were discrete and subtle from the outside. But there were huge shifts on the inside. That’s how change happens. There are these really small things that occur, this series of decisions that we make and continue to make that equal big change. And so I would say, looking back at my younger self, that I’m not so different than I am now. I was always a seeker. I wanted very ambitiously to be a writer and what happened between now and then is that I continually threw myself in the way of those things that would help me become that, of doing and finding and learning from things that altered me along the way.

As “Dear Sugar,” I write a lot about the importance of learning from experience. So much of what I’ve learned, so much of what’s good in my life, was learned because something bad happened, or from making the wrong decision. Through bad decisions I learned how to find the ways to make the right ones.

What about you, how have you changed?

Guernica: I’ve grown old with great enthusiasm, you know.

Cheryl Strayed: That’s what’s so weird. It’s been twenty years since we’ve seen each other.

Guernica: The last time I saw you, you were working as a waitress in New York. I was finishing my dissertation in Minnesota and coming to deliver a paper at Columbia. So I wrote you and said I’m coming, I’ll see you. You said, if you come, I’ll give you a free meal. It was great. I ate the pasta. Greedily. Now let’s talk about you and your writing.

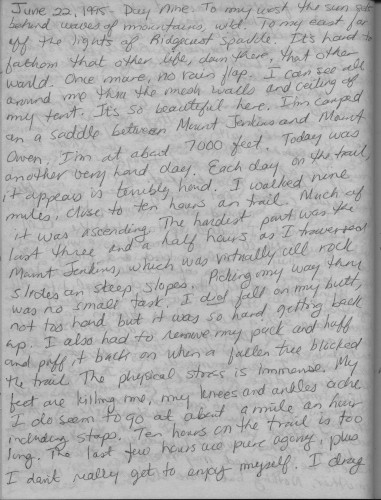

Cheryl Strayed: This is embarrassing, because when you asked for a page from my journal I honestly just opened it up and photocopied a page. I didn’t quite realize it would be here. It’s not brilliant by any stretch. It’s really just what I wrote that day. It’s very mundane and banal.

Guernica: What does it say?

Cheryl Strayed: [reading] “June 22nd. The physical stress is immense. My feet are killing me.” Which, you see, came to be a theme in Wild. “My knees and ankles ache. I do seem to go at about a mile an hour, including stops. Ten hours on the trail is too long. The last few hours are pure agony. Plus, I don’t really get to enjoy myself.” So you see those lamentations in Wild are true!

Guernica: Have you been a writer who has always kept journals?

Cheryl Strayed: I kept a journal all through my twenties and into my thirties. I essentially stopped keeping a journal the moment my son was born. Which was nine years ago today. The moment I became a mother it was no more lounging around in cafes reflecting on life. So, I always kept a journal, and this page is a fairly mundane example of it. On that page I’m essentially recording the physical reality and to some extent how I feel about it. But what I would often do in my journal without any sense that some day the story of my hike would become a book, is that I would often really write—my journal was my way to practice fiction writing.

When I met somebody on the trail, for example, and they’d walk away, I’d sit down and immediately write the scene of our meeting and I’d write it as if it were a scene. I’d put what they said in dialogue—what I remembered of what they said, and they had just said it a couple minutes before so it was pretty fresh—and I would describe them the way I would describe a character in a book. Which was great when I was writing, but Wild was by no stretch a direct translation of my journal. I didn’t turn my journal into a book, but rather my journal served as one of the sources I drew upon when I was writing the book.

Most of the conversations I wrote in the book are conversations I wrote from memory all these years later. I remembered that we talked about this, that, and the other thing, and re-conjured it in Wild. But some of the conversations were recorded in my journal. It was a great resource because I often wrote down that quirky thing that somebody said. There’s that scene where I meet the miners and they’re about to blow up that side of the mountain. The one man says something to the younger man: the younger man says he’s going to join the military, and the other man says, “And you never even said ‘Thank you’”—because he had also served. That was something I had because I’d written it in my journal. Or the hobo care package. That was also in my journal. All the contents.

Guernica: I initially knew you as a member of a small writing group. How important is it for young writers to be in supportive groups? Can you talk about your experience, and also why you chose to go to the MFA program in Syracuse?

Cheryl Strayed: I think the first thing—if you want to be a writer—the first thing you need to do is write. Which sounds like an obvious piece of advice. But so many people have this feeling they want to be a writer and they love to read but they don’t actually write very much. The main part of being a writer, though, is being profoundly alone for hours on end, uninterrupted by email or friends or children or romantic partners and really sinking into the work and writing. That’s how I write. That’s how writing gets done.

But that can be such a lonely endeavor that I do think community is also important. I have a writer’s group now in Portland, Oregon, where I live. Twenty years ago Amitava and I and this other woman named Trish would get together at cafes and exchange work and read to each other and give each other little bits of encouragement and feedback and thoughts. I think that’s an incredibly rich experience because what it does is it gives you a sense of community but also purpose. If I know I’m going to meet you in a cafe next Tuesday, I’m going to write something that I can hand to you. Discipline is such a challenge for so many writers and so I think that that’s a key benefit of being in a group.

Guernica: Happy birthday to your son Carver, by the way. He’s named after Raymond Carver, who used to teach at Syracuse, except that by the time you got there, if I remember right, he had passed.

Cheryl Strayed: I didn’t go to Syracuse because of him. But I certainly was excited he had been there. I did name my son after him, so, yes, I love Raymond Carver. What happened is that I was, all through my twenties, working as a waitress and writing, and I think that was the right thing to do. I had been in college and didn’t want to go straight from college to graduate school in writing, because I didn’t think that I was ready as a writer. I think that you should go into an MFA program when you’re solid in your identity as a writer and you’re going because you want to learn more and because you want that community of peers and mentors, not because you want to convince yourself you are a writer. So that’s when I went, when I was thirty. And I wrote my first book, which is a novel called Torch, when I was there.

Guernica: So it was a good experience for you?

Cheryl Strayed: It was a great experience. I highly recommend it, but not until a bit later. Of course some people manage to write books really young and publish really young. But for most writers, it takes several years because you have to apprentice yourself to the craft, and you also have to grow up. I think maturity is connected to one’s ability to write well.

[My mother] and I were both going through this experience together where educated people we respect are saying things like, “Oh, Michener sucks. You should be reading Moby Dick.”

Guernica: You know, we are very lucky today to have a very mixed audience. But we are going to persist just for a moment longer in talking about craft and training, so the students will benefit and then we’ll turn to more delicious things.

Cheryl Strayed: I know. I hope I’m not boring the people who are not writing. My feet are fine, that’s the main question I get from readers of Wild.

Guernica: Cheryl, there’s a paragraph on page 149. You are on the trail. Someone has given you a book. I’m about to ask you to read it.

Cheryl Strayed: [reading] “I looked at the book. It was called The Novel, which I’d never heard of or read, though James Michener had been my mother’s favorite author.

Guernica: What is this passage about, Cheryl?

Cheryl Strayed: It’s about class. At that moment where I was discussing those books in my twenties, I was beginning to understand what a culture hop I’d made growing up poor and working class and then going to college and suddenly being in this world where people were telling me essentially who I was. I didn’t know what my culture was until I went away from it and moved into another one. And one of the things that struck me most profoundly in college—and maybe some of you in this room know what I’m talking about—is that by going to college and becoming educated, I was becoming someone who was less like the community I came from and less like the family I came from.

Many of my peers, their parents were lawyers or surgeons or realtors or whatever they were, and they were on the path to becoming more like their parents, and I was on the path to becoming less like my parents. You know the funny thing is my mom was also on that path. She went to college when I did, and so she and I were both going through this experience together where we go to college and educated people who we respect are saying things to us like, “Oh, Michener sucks. You should be reading Moby Dick.”

And so there was this conundrum between high and low art, poor people and rich people, privilege and oppression, all of those things were presented to me in the form of simply what books you were allowed to read value.

Guernica: Yes.

Cheryl Strayed: It’s so complex I can’t even do it all justice right here.

Guernica: Now, for the next part of our conversation, the page will change. What the audience now sees on the screen is a manuscript page. I was interested in this because one of the things that happens is you have to edit your thoughts, and others edit you. It’s an edited life. I want to understand how one edits oneself, how one edits one’s identity, how one emerges as someone different, and also how other people do something to you and your words on the page. But before I ask you to answer all those questions, will you please read this passage from page 258?

Cheryl Strayed: In this scene, I’m with a guy named Jonathan who I’ve basically been having a little sexual adventure with for the past twenty-four hours. But meanwhile I’d recently divorced my husband—who I call Paul in Wild—and I still love him when Jonathan and I go to this beach and I realize I’d been at that same beach a year or two before with Paul.

Guernica: This idea of telling a story where you are already redeemed—it is the principle through which you have edited yourself into this person who has become such an important voice when she writes her columns. Do you see what I’m saying?

Cheryl Strayed: Yes

Guernica: Marilynne Robinson, a wonderful writer, a Pulitzer prize winner, is sometimes asked to deliver sermons at her church in Iowa. The Paris Review asked her what she does in these sermons. She says, “In my tradition, there’s a certain posture of graciousness you have to answer to no matter what the main subject matter of the sermon is.” The interviewer asks what she means. Robinson says, “The idea that you draw a line and say, The righteous people are on this side and the bad people are on the other side—this is not gracious.” This holds true in your writing, I think.

Cheryl Strayed: Thank you.

Do I think it was punishment for the book’s commercial success? Absolutely, positively: yes.

Guernica: Now, let’s talk about editing.

Cheryl Strayed: Any writer who knows what they’re doing will tell you that editing is such a huge piece of the journey. You do the writing and then in editing you have to re-enter the writing and take a bunch of stuff out and add a bunch of stuff in and make it better. That journal page that you just saw on the screen, I was writing with no consideration of you as an audience. I’m the audience in my journal. This page you see above me now is entirely this union of me writing privately while also having a strong vision of what I want you—the audience—to feel and think. And so you are constantly in my consideration in the editing process.

I think a lot of people have this idea of an editor being someone who comes in like a dictator, and says, “You can’t have that scene.” And it never is like that—or perhaps some editors are like that and they’re assholes, and they’re not good editors. A good editor actually says, “I respect you” and they understand that you have a vision and they’re actually trying to help you realize it. So, with Robin Desser, there was such a conversation, she considered every word. Sometimes we’d have these long conversations about whether this one word was the right word. Writing is such a strangely and radically private act, and yet its purpose is this great sense of connection and community. I mean, I wanted people to love the book. And the only way to get them to love it is to try to make it good for them. So of course the audience has to be considered.

My job is to simply keep doing the work. Like—well, you know—a motherfucker.

Guernica: The audience has to be considered and therefore you offer yourself as a sacrifice. I’m exaggerating. But what Steve Almond calls your “radical empathy,” in the foreword to Tiny Beautiful Things, is in a deep way your openness to share with others your failings. Here’s a note you put up on your Facebook page: “Going through a drawer I found the submissions/applications log I’ve kept off and on over the years. Just in case you think it’s all been roses I’d like to report that Yaddo rejected me (as recently as 2011). McDowell rejected me. Hedgebrook rejected me twice. The Georgia Review rejected me and Ploughshares rejected me and Tin House rejected me, as did about twenty other journals and magazines. Both the Sun and the Missouri Review rejected me before I appeared in their pages. Literary Arts declined to give me a fellowship three times before I won one. I’ve applied for an NEA [grant] five times and it’s always been a no. Harper’s Magazine never even bothered to reply. I say it all the time but I’ll say it again: keep on writing. Never give up. Rejection is part of a writer’s life. Then, now, always.”

Can you talk a bit about what you’re doing here? Do you ever doubt yourself when you offer such help?

Cheryl Strayed: What I’m doing is telling the truth and no, I don’t doubt myself when I reveal my own failures and vulnerabilities. The strangest thing to come out of Wild’s success is how often people make incorrect assumptions about me. They assume writing is easy for me and I’ll never face rejection again. But of course I will and I do. The thing I’ve learned over and over again is never, ever assume that you’re going to get something—publication, award nominations, a prize, a residency, or fellowship. And never assume you aren’t going to get it either. The writing life doesn’t move in a straight line. I’ve had successes and rejections all along the way, at every stage of my career, and I will continue to do so. Acceptances and rejections don’t define me. They’re both part of what it means to be a writer. My job is to simply keep doing the work. Like—well, you know—a motherfucker.

Guernica: Dani Shapiro called Wild “a literary and human triumph” in the New York Times Book Review. Dwight Garner, reviewing it in the same newspaper’s main pages, raved about “the writer finding her voice, and sustaining it, right in front of your eyes.” But your book wasn’t included among the ten best books of the year. Egregiously, it didn’t even feature among the hundred notable books of the year. What gives?

Cheryl Strayed: This proves my point about rejection. You really can’t focus on such things or it will kill you. I’d never presume that Wild should be on anyone’s list, but that the NYTBR left it off their hundred “notables” at the end of 2012 was rather striking. Do I think it was punishment for the book’s commercial success? Absolutely, positively: yes.

First audience member: I’m a clinical psychologist, and I was struck by you saying you’re not a therapist. I just came from a conference of psychoanalysts, and what you just read is more connected to the human condition than what happened at the conference.

Cheryl Strayed: Thank you. If things hadn’t worked out so well with Wild I was going to hang a shingle out actually. When I say I’ve never gone to therapy I don’t mean to knock it. I want to and I often tell people who write me that they should. I think therapy is useful. It’s essentially looking deeply at what it really means to be human—just like I try to do in my writing. One of the coolest things about the “Dear Sugar” experience has been that I’ve gotten so many letters from therapists who say they use the column in their practice. As Sugar, I’m able to do what therapists are often not allowed to do because you have professional restrictions—codes that are in place for good reason. But, as Sugar I can say whatever I want. I’m grateful that the column’s been used by therapists.

First audience member: In reading the book as a therapist, I was interested in your walk on the Pacific Crest Trail and how you presented it as very healing. But as I was reading, I was also struck by elements of self-destructiveness.

Cheryl Strayed: I wrote this book as the older self, the self that’s grown beyond those years that I wrote about in Wild. So I had some perspective on it. When I think about my decision to use heroin, or to be promiscuous, to do things that were self-destructive, I really think even in doing those things I was trying to heal myself. Our culture doesn’t have rites of passage traditions, and in so many ways I needed one. I was an orphan, I was in grief, I was in my twenties, trying to figure out what I’m going to do and who I am—which you have to do even when things are going great.

And so I was trying to throw myself into danger. I was always putting myself up against risk and the Pacific Crest Trail just happened to be a healthy way of doing that. All rites of passage entail an element of suffering, usually physical suffering, and I think I was enacting that on my hike with my heavy pack. I was enacting what I felt on the inside and it ended up being like a cure for me.

Second audience member: You wrote Wild long after the experience discussed in the book. What prompted you to write about this now?

Cheryl Strayed: When I was taking the hike, I wasn’t thinking I’d write a book about this experience. I didn’t take the hike to write a book about it, though I was a writer at the time. In Wild, I write about this book that I was writing in my head. That was my first book, Torch. That was the book I had burning in my bones and I had to write it. So I did that—Torch was published in 2006—and after that I started to think, what’s the next story? The way I often find what I’m going to write next is by writing. All these years, people who know me would tell me: “You have to write about your hike on the Pacific Crest Trail.” I’d say, “Until I have something to say about it, I don’t want to write about it. We’ve all had adventures, traumas, dramas, we’ve all had all kinds of experiences, and that does not necessarily make a memoir.”

The point of Wild is not, “I did something nobody’s ever done before.” A lot of people have hiked a long way, longer than me, better than me, braver than me, everything more than me. Wild does not hinge on: I did this big thing. What it does hinge on is the consciousness I brought to bear on this big thing. What do I have to say about this experience? So first of all, I needed to have some perspective. I needed the passage of years so I could understand myself in my twenties. When I was in my twenties, I was too close to the experience. As I grew up I could see what I’d passed through and how it was made manifest in my life.

After Torch came out, I thought, well, maybe I’ll write a little bit about this hike. So I started writing an essay—I thought I had about twenty or thirty pages of material that I could tell about this hike—and I started writing it and I was writing and writing and I was maybe ninety pages in, and I still hadn’t even set foot on the trail. And my writers’ group kept saying, “This is a book, this is not an essay,” and I kept saying, “Well, I’ll trim it back,” and they’d say “No, no, it’s a book.” And my husband had been telling me the same for years. So finally I realized I had a book.

Third audience member: The piece “Write Like a Motherfucker” is fantastic. I guess on the other side of that, as a professional writer, I have to meet deadlines every single day. How do you stop that and go back to the quiet place where things just kind of come? What is your advice?

Cheryl Strayed: I know, it’s maddening! It’s so hard, because you have to make a living, or most of us have to. I certainly had to, and have to still. So it’s really this balance between doing things you have to do because you need the money so you can pay the electric bill, and then doing that thing you really care about, your passion. I’ve done different things over the years.

One of the things I did is I never made excuses for myself when it came to writing. I prioritized writing time. Even if that meant taking risks financially. I’d apply for residencies—places that give you a free place to live and they feed you and sometimes also provide a stipend—and go off and write for these intensive periods of time. That’s why I was a waitress, because the job never meant anything to me, so I could quit. I’d quit my job if I got a residency or a grant and I’d go off and write.

The other thing I did more recently, once I became a mom and my kids were old enough that I could leave them for a short time, is I would just check into a hotel right near our house, you know, like, the Courtyard Marriott a half a mile from my house in Portland. I’d check in for two nights and I’d write more in those forty-eight hours than I would for weeks at home. So just finding all these different creative ways to say, this thing actually matters and we’re gonna do it, and we’re gonna do it whether we have the money or not, or we have two little kids, or whatever it is. And I know it’s hard. I mean, I truly know it’s just plain hard. But do your best. And really actually do your best. Ask yourself: What is the best I can do? And then do that.

To contact Guernica or Cheryl Strayed, please write here.