Lana Bastašić’s debut novel, Catch the Rabbit, opens with an arresting first-person voice—a narrator called Sara half addressing, half writing about her childhood friend Lejla, who phones her in Dublin from the Balkans after a twelve-year silence.

“You have someone and then you don’t. And that’s the whole story,” Sara writes of the friendship, though Lejla, she stresses, would contradict this. “She would say you can’t have a person. But she would be wrong. … Only she likes to think of herself as the general rule for the workings of the whole cosmos. And the truth is you can have someone, just not her. You can’t have Lejla.”

Having and not having someone is not the whole story between these friends. Theirs is a narrative with any number of beginnings, Sara tells us, and she opts to start with Lejla’s call. “Hello, you,” says the voice on the other end when Sara answers.

Standing in St. Stephen’s Green, Sara can only manage to say Lejla’s name, but Lejla rambles on as if they’ve never lost touch. In fact, she’s called to ask a favor — to insist on one. She wants Sara to pick her up in Bosnia and Herzegovina and drive her to Vienna. “I’m still in Mostar,” she remarks, as if Sara should know she ever moved there.

Rooted to her spot beside an oak, Sara adds up not just the years, but the seasons — forty-eight — since she last heard Lejla’s voice. She feels the world around her slow to a halt. “Lejla showed up, said cut, and everything froze,” she thinks. “Trees, trams, people. Like tired actors.” Meanwhile, Lejla presses her case: “You gotta come get me as soon as you can.”

After no word for twelve years? And now a language Sara rejected — along with her family and her country, which she left as an adult — is back in her mouth. Just uttering Lejla’s name brings her mother tongue like a system of roots up from the mud, as Sara imagines, and with it, a fraught personal and collective history. She refuses and hangs up the call.

But when Lejla phones again and utters the magic words—“Armin is in Vienna”—Sara pauses. Armin, Lejla’s brother, who disappeared in Bosnia and Herzegovina during the Yugoslav wars of the 1990s when Lejla and Sara were kids. Armin, whom Sara loved and about whom she bears a complex burden. Armin, who as a missing person seems to hold all the weight and trauma of that period. These many years later, Armin is in Vienna.

“You gotta come pick me up,” Lejla pleads. Sara buys the ticket.

Over roughly the last year, several books by authors from the former Yugoslavia have been published in English translation in the US, some grappling, directly and indirectly, with the ’90s wars, trauma, displacement, and how one lives in aftermath. As we continue navigating the pandemic — a different kind of trauma, suffered unevenly, another sort of gash across time, place, families, cultures — the wave of contemporary literature arriving in English from the Balkans seems timely and resonant, in part for the questions it raises: How do we understand a before and after? Can we knit ourselves back together? What does it mean to be whole?

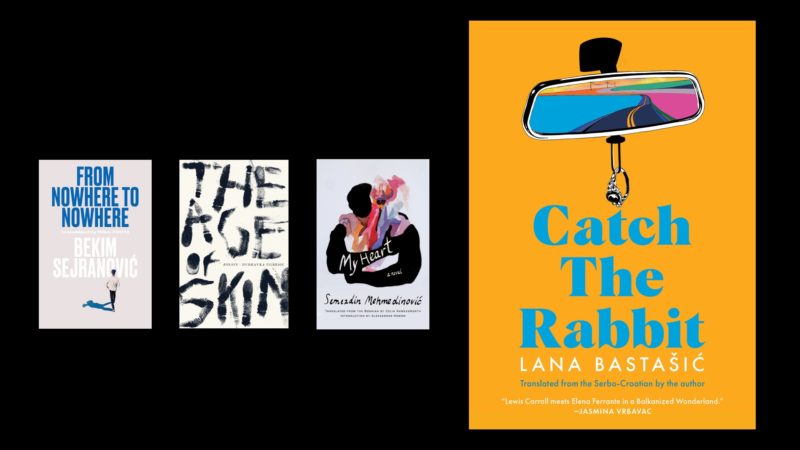

Neustadt Prize winner Dubravka Ugrešić’s essay collection The Age of Skin, translated by Ellen Elias-Bursać, considers the present-day ruins of the post-war Balkans. She describes “life mid-rubble” as a “continuing condition.” Semezdin Mehmedinović’s novel My Heart, translated by Celia Hawkesworth, takes on memory loss — the narrator’s own due to medication after a heart attack and his wife’s after a stroke. As the story plays out near Washington, D.C., and in the American West, the narrator pieces in scraps of remembered life from Bosnia and Herzegovina, turning over these fragments in an extended meditation. “There’s a year in my past I’ve never left,” he writes. “1992.” The start of the war. The narrator of Bekim Sejranović’s From Nowhere to Nowhere, translated by Will Firth and brought out by Sandorf Passage (a new US-based publisher of work from the region), travels between Norway and the Balkans, between past and present, standing over graves, grieving and remembering, in a disjointed account fractured across time. “You don’t know what causes more pain,” he reflects, “memory or the truth.”

Bastašić’s Catch the Rabbit, which won the European Union Prize for Literature and which Bastašić translated herself, likewise shuttles back and forth across time, across the chasm of the war — the “darkness” as the narrator, Sara, calls it — laboring to create a kind of linkage between one life and another, to understand the gash through a friendship, a world, as if to fit back together a self. These efforts become more pressing as Sara and Lejla make their way to Vienna.

After recounting the phone call with Lejla, Sara takes us back to the last time she saw her friend, twelve years earlier. The two women, who’ve just graduated from college, come together, here too after a break in the relationship, to bury Lejla’s pet rabbit. Sara digs the hole and, at Lejla’s urging, reluctantly gives the eulogy. “You’re the poet,” Lejla quips, which is true: Sara has already published a book.

The meeting is tense. “I can’t remember whether we returned the shovel to the neighbor, whether we said anything else or not,” Sara tells us, looking back. “I only know that later that night [Lejla’s] head was heavy on my inadequate shoulder and how I cursed both that shoulder and the brown couch cover which had hardened into asphalt between us. We were looking at her pale brother contained inside four paper edges while her mother banged on in the kitchen.”

Between that paper photograph of Armin, the dead rabbit, and other references woven into this scene, we are ushered unawares into the book’s mystery, as if handed the end of a thread that we’ll clutch through the labyrinth of the book, all the while lured by Sara’s voice. By her frustration. By the subtext. “A blonde girl in plastic slippers who could joke about the rabbit that … she used to love more than people,” Sara says of her friend, still remembering that long-ago night. “A girl … who doesn’t talk about her brother. Someone’s frail, dumb muse. I couldn’t stand her.”

When the two finally meet again, this time in Mostar, Sara finds herself overcome, not by the old admixture of anger, but by yearning. She observes Lejla outside the restaurant where she works, dressed in a kitschy Ottoman costume, smiling for tourists’ photographs, and feels thrust into the friendship’s former dynamic. “I was once again ready to be nothing,” Sara concedes, “…or at least turn into one of those cats at her clogs, just so she would talk to me, fill my ears with us, with what we had once been.” It will take the road trip for Sara to expose her vulnerability to Lejla.

We journey with them across Bosnia and Herzegovina, Lejla throwing things out the car window — her used tampon, cassette tapes—while Sara rebukes her. Lejla has bruises on her body, some like fingerprints; Sara doesn’t ask, honoring her friend’s “right to silence.” They visit the catacombs in Jajce, where Sara tells Lejla she’s had her “tubes tied.” She doesn’t want to “be continued” as a person, she explains — to us, not to Lejla. They pull into Banja Luka, their hometown, where Sara flees from her family’s house and, in a surreal moment of distress, envisions a statue come to life and hold her in his arms. Later, Lejla runs their car off the road, and the two women lose themselves in a corn field. All before they cross the border, driving on to Zagreb and then to Vienna. Notably, they don’t discuss Armin.

The road trip carries us forward, while underneath, the past smolders. Each chapter toggles between the present journey and some piece of Sara and Lejla’s history: Armin and the question of what happened to him as a teenager in wartime. Sara and Lejla’s trip to the market after prom when an earthquake strikes and Sara steals the pet rabbit for her friend. Lejla’s slapping Sara in the face when the two are in college, in effect ending their friendship over a remark about Armin.

Reading, we sew the pieces together. In the present, we watch the two friends and listen to their interaction. In the past, we often overhear as Sara addresses her narrative to Lejla: “Armin disappeared after all the dogs had died. After untying my hair. After your menstruation. He, you, and I in your backyard, next to the cherry tree, your earring in my pocket. Surrounded with grass, cigarette smoke, and my messy hair, I didn’t know I was already standing in a mutilated future memory.”

There is a third dimension in the book — a meta-narrative. Sara, we understand, is writing her account after the road trip. Both a poet and a translator, she constructs the story — of the friendship, of the two women’s lives — partly as a way to wrest meaning out of the past, to uncover a “point,” as she later considers, using Lejla’s word, which is more like an accusation. “That’s what everyone wants, right?” Sara remarks, writing to her now-absent friend. “Someone to give them a theme, a motive, a setting? The beginning and the end. A point. That’s why you hate them.”

Sara’s need to understand, to locate a shape in their history, emerges in the language — in a proliferation of metaphors and comparisons, her effort to comprehend one thing by way of another. Lejla is “queen of darkness” and sees life as a “rabid fox coming at night to steal your chickens.” On the road trip, she sleeps just as Sara remembers: “like she was dead.” Their hometown, Banja Luka, is a “cold grave in the middle of our itinerary.” Memories are “like a frozen lake”— you can reach in through a crack and “catch a detail, a recollection in the cold water.”

But how useful is recollection? What is reliable? What “fake scaffolding,” Sara wants to know, has to be created or revised? “I can barely remember a thing,” she writes as a kind of refrain. “I have to invent an olive tree and mosquitos and get all the senses working, right? … As if the story would be alive then.” The book pulses with a relentless energy, with Sara’s will to get to the bottom of something. To get to Vienna. To Armin. To the bottom of that frozen lake.

A blurb on Bastašić’s book links the novel with the work of Italian writer Elena Ferrante, whose Neapolitan quartet explores a turbulent, lifelong friendship between two women. Whether a comparison between the two writers illuminates our reading of Catch the Rabbit, something about the dynamic between Sara and Lejla — their roiling, symbiotic connection — does evoke the friendship at the center of Ferrante’s quartet. One woman, in this case Lejla, seems to live in her own skin, unselfconscious, explosive, beleaguered, original, while the other — the more polished Sara — observes, describes, projects, and longs as one would for a lover. We see the friendship blur into Sara’s desire to possess — to become — the other, a portrait that at once resembles and transcends Ferrante’s.

Sara and Lejla’s friendship is further complicated by place and time. By history. War. A difference in ethnic identity. In Banja Luka, a city that served in wartime as the hub for the Bosnian Serbs, Lejla’s family is from a Muslim background, Sara’s a Serbian one. As tensions mount, Lejla’s mother changes their surname, and Lejla becomes the Orthodox Lela. (Years later, Sara is the only one who uses Lejla’s original name.) On the other side, Sara’s father serves in the city’s power structure as the police chief. He hits Sara’s mother. He dismisses Armin’s disappearance, rebuffing Lejla’s mother when she comes to him for help. Out of his mouth proceeds a river of slurs. “Six months and you close the case,” he says perfunctorily of Armin during a meal, using a line Sara won’t forgive or forget. Still, after the war ends, she doesn’t grant Lejla’s request that she ask her father to look again into what happened. Even now Sara remains unclear about her own silence — she carries a burden of guilt about Armin — but when her father dies, she doesn’t attend his funeral.

Driving through the country with Lejla, Sara experiences an almost unnavigable darkness — once they leave Mostar, the afternoon sky is swallowed by it. When they reach their hometown, Banja Luka, the quality of the darkness changes: “There was a thickness to it which mixed with the air so that I was surrounded not by a lack of light, but with a living, tangible substance.” While Lejla visits her mother, Sara is left to feel her way through the streets in that dark, as if entering the realm of the unconscious or an underworld of the recent past. She walks by old and half-finished structures. Among shadowy figures — the elderly, moving “as if pulling beached ships behind them.” Until she finds her family’s house, “a tombstone of a home overgrown by weeds.” She hasn’t talked to her mother in years, as if to finally cut away everything connected to her past trauma and feelings of guilt. Now, hidden behind a bush, she watches as her mother eats grotesquely at a table in the yard, a scene from which Sara runs.

Back on the road, the darkness becomes “looser,” and by the time the two women cross the border into Croatia, Sara is aware of having fulfilled a mission. “Now that I had taken Lejla out of it and knew that Armin was somewhere else, Bosnia had lost its entire purpose. Like someone had taken its two batteries out.” The energy never drains out of the novel, as if Bastašić’s ambition were to set down an entire psyche. More than that—a world. She holds everything together: details, imagery, language, pieces of narrative. No thread is dropped. Lines of the story converge. When we reach the end — Vienna and the designated meeting place — we are both prepared and unprepared for it.

Leaving Sara and Lejla in Vienna, we don’t know how they will fare. Something has been understood, and we’re left to consider what understanding — at most, partial — can yield. If human beings are wired to seek or make meaning, then Lejla rejects this process. Sara, too, has doubts. “Perhaps you were right the whole time, perhaps there are no points, no hidden patterns under the surface of life,” she writes late in the story. Yet she continues to look. And even Lejla, in planning their trip — leading them to Vienna — creates an arc or pattern of her own.

While the world tries to emerge from the darkness of pandemic, we face questions about how to reassemble ourselves across the gash. How to look back, and whether we can bear it. How to make sense of the losses, the suffering, the vanished time. How to connect who we were before to who we are now. In this, Catch the Rabbit, along with other books from the Balkans coming out in English translation, offers not so much a “point” as a way, depicting the effort to recover, to drag something out of the ruins, to catch light.