I have folders of material that I didn’t use in We Take Our Cities With Us: A Memoir. At various points, I wrote about images that I’d excavated during the research into my mother’s life, a process that (I realize now) I adopted from researching my novels. These paragraphs do not appear in the book, but they helped write it anyway.

1.

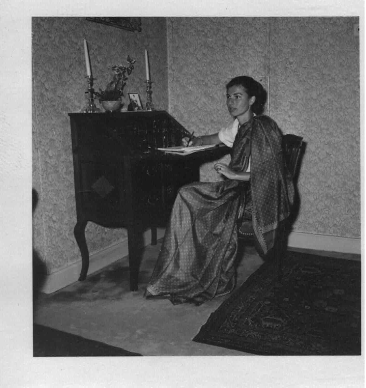

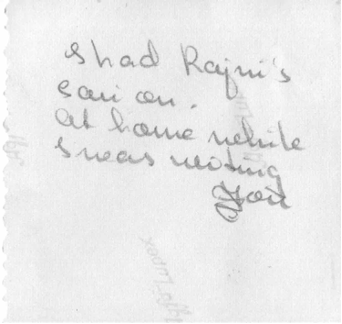

I’ve studied my mother’s photo albums for months, yet the two-inch black-and-white photograph, buried in among other matte images at the back of one album, surprises me. My mother is wearing a poorly ironed sari and is sitting at the antique desk of our childhood home. The desk’s delicate front is drawn down, and my mother leans against it and writes. She is younger in that image than my children are today, and I want to reach into the scene and support her weight. Carefully, I slip the photograph out of its yellowed corner tabs, tearing two as it comes loose. I turn it over, hoping for a date or confirmation of Minervaplein, but find neither. My mother writes, “I had Rajni’s sari on. At home while I was writing you.” The you can only be my father, and I imagine the photograph as one of several my parents exchanged in onion-skin or linen-paper letters, hopeful that images would bridge absence and distance. I shouldn’t, but before I scan the photograph and send it to my siblings, I trace my mother’s young face, radiant with concentrated love, and wonder if my father did the same and whether his fingerprints, like his life, are now forever mingled with mine.

2.

Churches hold answers, even if that’s not what my mother thought when she fled the church into the arms of my father and Islam. The Maastricht archive is in the Gothic church of a thirteenth-century Franciscan monastery; it is older than any mosque in Pakistan. The ceilings are immense like the heaven they promise; the light is sharp and less forgiving. I take my place at a table of microfilm projectors where other researchers also pursue the past. One of them will eventually send me the date and time of my great-grandmother’s funeral, along with an entry on an old train schedule, as if it were still possible to attend. I slip a film between two plates of glass and, for several minutes, all I see is illegible script. I wind my way through birth certificates, rushing across years the way we do with our lives, before I recall his birthdate, which is a Valentine’s Day, 150 years ago. I slowly reverse toward it and, there, on a dotted line, a clerk has written my great-grandfather’s full name, which only has a single syllable. I skate through time a little longer, backward and forward, backward and forward. When I finally leave the archive, I stop in the church choir room. Gravestones that were once laid like ledgers into the floor lie scrubbed and polished on beds of iron frames, as if on exhibition. I run my hand over the smooth cold stones, dipping my fingers into the crevices of worn names and the raised carvings of the dead. In the stillness, the past and present, like history, are everywhere and one.

3.

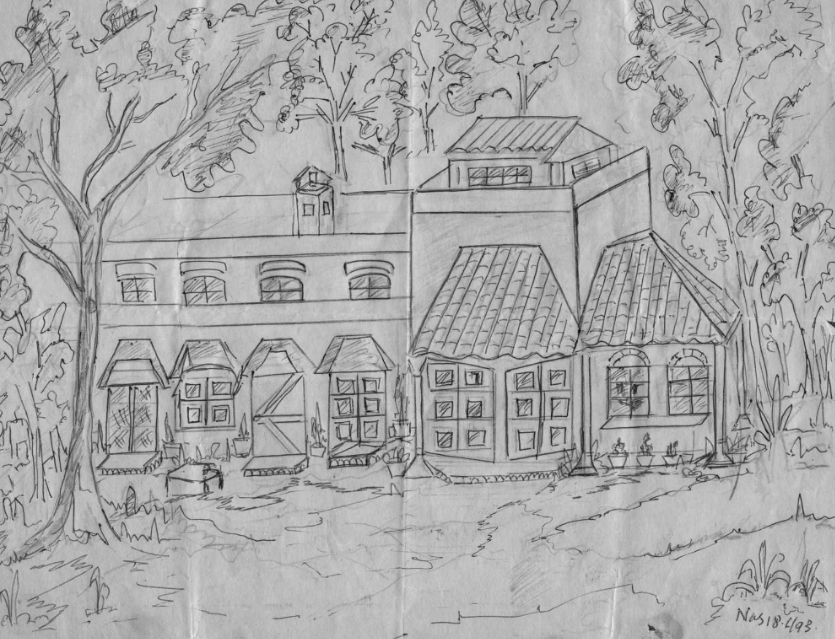

The house locates me. As a child, it located me in an extended family and in a country that wasn’t fully mine. It locates me as an adult, far away now from a place that only exists in my memory and in the memory of those who passed through it. It lives inside me as a distant place, parallel and still alive, complete with revving car engines, squealing bands of children, the stench of open sewers the width of a child’s flip-flops. It occupies me in fragments, like the past does.

I have scoured family photo albums for images of 5 Queen’s Road, Lahore, but there are none. Yet there are hundreds of photographs and slides of friends and relatives on the patio. In between the subjects, or surrounding them, are slivers of the house: verandah lattice, pock-marked wall, sagging bamboo shade. My father, who was reluctant to go anywhere without a camera around his neck, did not take a single panorama of the house.

Long ago, during a visit home to Pakistan, I asked my youngest aunt (an artist until she wasn’t) to draw 5 Queen’s Road. As her parents’ long time caregiver, she’d been a resident much longer than her siblings. Each time I saw her that summer, I reminded her, and she smiled my father’s smile and made no promises. I’d all but given up the night before my departure, when my father rushed into my bedroom and delivered her sketch.