By Rachel Riederer

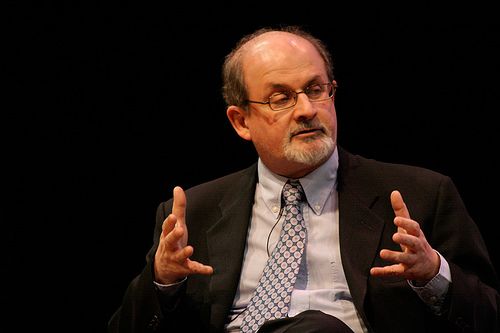

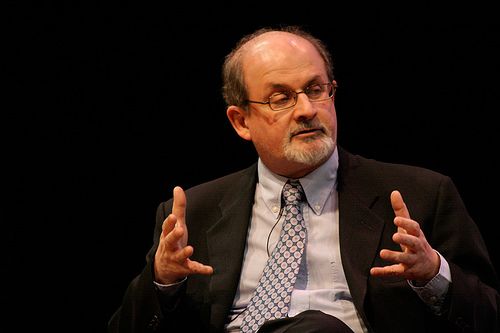

Last Monday at a little bar inside Tribeca Cinema, the Asian American Writers’ Workshop honored Salman Rushdie with a lifetime achievement award. A crowd gathered to hear readings from Rushdie’s work and listen to him answer questions about the craft of writing. The atmosphere was one of revelry—grinning fans taking cellphone photos of themselves standing next to Rushdie. In such a love-fest, it is hard to remember that this is the same author who had to cancel his appearance at the Jaipur Literary Festival last year amid rumors of an assassination plot, that when Hari Kunrzu and Amitava Kumar read some passages from The Satanic Verses to festival-goers as a show of support for Rushdie, the action caused such a stir that they had to hustle not just out of the festival, but out of India.

The evening opened with Jonathan Safran Foer and Téa Obreht reading from Rushdie’s work—Foer from The Moor’s Last Sigh and Obreht from Rushdie’s recent memoir, Joseph Anton (when police told Rushdie to invent an alias post-fatwa, he chose this combination of Joseph Conrad and Anton Chekov—it’s not a lifetime achieve award for modesty). Both writers shared strong memories of the moments they spent reading or listening to Rushdie—the kind of seared-in memories that come from reading an author whose language is so singular, so unmistakably his own. Obreht recalled Rushdie visiting Cornell while she was studying there. When a student at a panel asked Rushdie how he developed his signature “verbal gymnastics” Rushdie answered that it was simple: “I go to the verbal gym!”

Reading Forster was formative, Rushdie said, because he realized “even though I admire him, that’s exactly what I don’t want to be.”

Zadie Smith read last. Instead of reading from Midnight’s Children as she originally planned, she read—at Rushdie’s request—a passage from White Teeth that alludes to Rushdie and the protests over The Satanic Verses. A group of teenagers are riding the train to a rally, talking about the unnamed author of the offending book. One admits that he—like many real-life people who condemn Rushdie’s work—is unfamiliar with the actual text. “You don’t have to read shit,” says Millat, “to know that it’s blasphemous.”

After the readings, Rushdie sat down with Amitava Kumar to talk about life and craft. When asked about influences, Rushdie cited E.M. Forster, who had a kind of “reverse influence” on his writing. Reading Forster was formative, Rushdie said, because he realized “even though I admire him, that’s exactly what I don’t want to be.” Instead of Forster’s coolness and distance from his subject matter, Rushdie wanted to write prose that was “hot.”

Rushdie also talked about the labels that get applied to writers of color and non-Western writers. “Western writers have never doubted that their subject matter is interesting—even if it’s very local or parochial,” he said, and advised all writers to “just make the same assumption.” He also noted that Western writers have also felt free to write about any place in the world, not just where they’re from, and “nobody calls them deracinated.” He was buoyed by the fact that Indian writers are now embracing this same freedom, and writing fiction set all around the globe, refusing “to be caged by origin.” When asked if he had advice for young writers trying to escape being pigeonholed by where they’re from, Rushdie answered quickly and with a big grin: “No tropical fruit in the title… avoid that shit.”

Rachel Riederer is the editor of Guernica Daily.