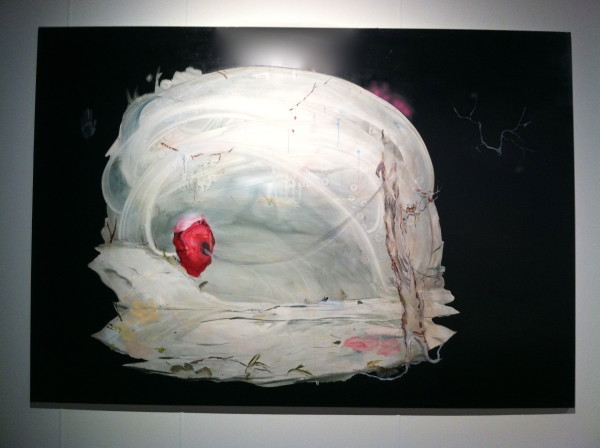

The 2014 Biennale of Sydney opened on March 21st and has run for 13 sunny weeks. Director Juliana Engberg traveled the globe to gather close to 100 participating artists from 31 countries. Her theme: You Imagine What You Desire. While some artists responded with utopias of joy and whimsy, others engendered darker worlds of pain, obsession, and loss. When I asked what tied her various chosen works together, Engberg said: “Birds are everywhere. Air and water are everywhere, so are earth and fire. Elementally, it’s kind of a set of necklace nodules strung together. And then there are the lovely light works of Nathan Coley that blink away in the night time, that remind us that we create what we will—hopefully a better society.”

The idea of a better society was well at the forefront of this year’s controversial biennale. In February news broke that the event’s main sponsor, Transfield Holdings, has a 12 percent stake in a company that operates offshore detention centers housing asylum seekers on Nauru and Manus Island. Australia’s mandatory detention policy has been a hot-button political issue since its establishment in 1992, with vocal critics citing human rights violations and the unethical profiteering off asylum seekers. In early 2014, 23-year-old Reza Berati, an Iranian, died on Manus Island, and over seventy people have required medical treatment. After creating the #19BoS Working Group, 51 participating artists signed a letter to the Board of the Biennale requesting they end their funding arrangement with Transfield. Following the Board’s response—that the sponsorship arrangement would remain in place—nine artists withdrew their work. Then another plot twist: Transfield itself withdrew sponsorship and Luca Belgiorno-Nettis, Transfield’s executive director and the biennale’s chairman, resigned from the festival. Ultimately seven of the nine artists returned to the fold.

I attended the biennale this year and closely followed the abundant local coverage of the controversy. In scores of articles, various participating artists are quoted, usually a sentence or two or three. But I wanted more. I knew from personal conversations with artists how nuanced each of their responses to the controversy were – how seriously they had considered the issues at hand and weighed them against a context which for some felt very personal and for others very far away, questions of personal responsibility, the most effective strategies of activism, and more.

And so I approached a group of participating artists with a very annoying request: I asked these people who have already discussed this sponsorship controversy ad nauseam to talk about it once more. I offered a short list of guiding questions about the controversy but asked them to respond however they saw fit. Together their comments provide a compelling portrait of the interconnections between art, ethics, politics, and nationalism. I’ll let them speak for themselves.

—Rachel Friedman for Guernica

Nathan Gray

Born in Perth, Australia

Lives and Works in Melbourne, Australia

During install of my work I was informed by a friend of mine that Transfield, the founding partner of the Biennale, was taking on the contract to provide welfare services to Manus Island detention centre. Welfare is an area in which the company has never worked before. I, like many Australians, am deeply concerned with the plight of refugees and asylum seekers.

Soon after I found out about the welfare contract, riots occurred on Manus Island and more than 60 people were beaten, one shot, one had his throat cut, one lost an eye, and Reza Berati lost his life. These events are still under investigation by the courts in Papua New Guinea.

Days later it was announced that Transfield would be taking on a much larger contract, one which would see them running both Manus and Nauru camps, a contract worth $1.2 billion.

Shortly after this, I became aware of calls to boycott the Biennale from various refugee action groups, and public meetings in both Melbourne and Sydney were called to discuss the situation.

Myself, Bianca Hester, Charlie Sofo and Gabrielle DeVietri formed the Artist’s Working Group and drafted a letter to the board after consulting with them and the curator Juliana Engberg. This letter was signed by 51 of the contributing artists. This letter was met with a response that the Biennale would stick with its sponsors.

The next stage saw Gabrielle DeVietri, Charlie Sofo, Olfur Olaffson, Libia Castro and Ahmet Oghut withdraw. Then a week later Agnieszka Polska, Nicoline Van Harskamp, Sara Van der Heide and myself withdrew.

At the end of that week the Biennale stated that it was severing all ties with Transfield and I was invited back into the Biennale. The board having acted on our concerns, I felt that I should no longer withhold my labor.

Increasingly, divestment is proving to be an effective strategy against the type of corporate excesses that government is unable or unwilling to curb. The rise of 350.org as a means of tackling climate change has seen some of Australia’s pension funds divest from fossil fuels, and already we have seen several unions requesting that their pension funds divest from mandatory detention, though with limited success so far.

The logic of corporations, whose only ethical concern is to return a profit to their shareholders, forces us to translate human ethics into profits in order for human ethics to become intelligible to the corporation. During the campaign we saw Transfield’s stock price slowly decline, despite the fact that it had just been awarded a billion-dollar contract.

The efficacy of the campaign was due to several factors. One was the timing being so close to the Manus riots and another was the consistency of message; that the Biennale should divest from Transfield. This message was applied from many directions; the artists who boycotted, those who signed the letter, other arts organizations, media, intellectuals and third-party sponsors.

Artists who boycotted and those who stayed did not allow themselves to become opposed but continued to work actively together achieving a greater total effect than a simple boycott might have.

There were also claims that all funding is tainted or that there is no “clean money,” which ignores the fact that there is “better money” and “worse money.”

The criticism generated by the political action was revealing. The artists’ call to “become aware of, and to acknowledge, responsibility for our own participation in a chain of connections that links to human suffering” was itself called irresponsible. The implication that artists should care for arts institutions and their corporate sponsors over human rights is a limited notion of responsibility rather than a wider notion of collective responsibility proposed by the artists.

Guido Belagiorno-Nettis stated in his opening speech at the Art Gallery of New South Wales that the appropriate place for artists to protest was within their work and the institution. To me this highlighted the confidence of corporate interests in their ability to co-opt institutional critique, and was an attempt to discount the contemporary artist’s role as media figure, ignoring some of the many platforms contemporary artists work across.

There were also claims that all funding is tainted or that there is no “clean money,” which ignores the fact that there is “better money” and “worse money.” Obviously a corporation involved in solar power is preferable to one involved in arms manufacture.

In my opinion the focus on ethical sponsorship for the arts diverts attention from divestment strategies that can successfully be used to change government policy and political outcomes. My question would be: why should ethical funding just be for the arts?

Lastly there has been the continued insistence that art occupies a space outside of finance. This is precisely the logic that allows corporations to gain brand value by using arts events as promotional events. The promotional value of many arts events is greatly inflated by government funding and by the systematic underpaying of its primary workers: the artists themselves.

Essentially the political action around the Biennale was one that acknowledged the financial value of the artists as primary generators of a spectacle that corporations use to increase their prestige, and by acknowledging this, the artists were able to leverage their power as a sought-after skilled freelance workforce through the threat of withdrawing their labour.

Claims that art exists in a space outside of finance are untrue. This recognition does not limit art’s ability to have roles that are more important, nuanced and imaginative than financial ones but it does empower artists to affect change through their role in arts organizations and set examples for workers in other industries to do the same.

Anna Tuori

Born in Helsinki, Finland

Lives and Works in Helsinki

The question of art, money and morality is an endless loop. What is good money? What is bad? How about government support? Many governments participate in acts that hover in the grey area of morality. And how about arts grants as a concept, a principle? Shouldn’t the money go to the starving children rather than artists who take pictures of starving children? And so on. Should we overcomplicate the questions or oversimplify them? Sometimes we artists behave like we invented this thing called morality and we seem a little too happy to toy with it and not notice that the world around us is not always so clear-cut as we hope and demand.

An older gentleman likes one of my paintings. He wants to buy it. I happily sell it to him, because I need the money, but should I first make inquiries about the gentleman and his money? Did he become wealthy destroying nature, selling arms, making leveraged buy-outs that lead to thousands of unemployed? Or should I just take the money? (And should we also include the history of art and patronage here? Goya, Shakespeare—should we dismiss them because they accepted money from kings, queens and popes, who thought that war is actually a good answer to almost anything?)

[The Biennale Boycott] was too much about art and capitalism and other worn out dichotomies.

There’s this arrogance that I’m somewhat uncomfortable with. Here am I, an artist from Finland telling the whole of Australia what are the choices they have to make so I can live with them. Maybe there’s just a tiny possibility that all kinds of conversations about morality, government policies etc. had taken place before I came to the scene shouting that I’m an artist from Finland, and because I’m an artist from Finland, you have to listen to me and take seriously my misgivings about your decisions. It implies that people in Australia didn’t know and care about the camps before me, but lucky for them I managed to open their eyes. And I really don´t mean that we all should just let things to be like they are with crimes against humanity.

Human rights are the most fundamental question and one must always be prepared to uphold them. That is the litmus test of basic humanity. One must fight human rights violations in every possible way in every country. In fighting against these crimes I am for commercial boycotts, strikes, protests and all the old and new ways that have been proved fruitful. The problem for me with the Biennale boycott was that it was maybe directed to slightly wrong targets. In rallying against Transfield’s sponsorship in Biennale, it almost forgot the inhumanities and suffering refugees. It was too much about art and capitalism and other worn out dichotomies. It was too much about symbolism, how things look, and too little about the thing that mattered: refugee camps and the people in them.

Australia has signed the UN’s Conventions and protocol relating to the status of refugees (UNHCR). Nevertheless it acts against the UNHCR. The UN should do something about Australia’s violation of the treaty it has signed. So the problem here is not solely the ever so easy target capitalism. In Transfield’s case it acts in accordance with the Australian government. The real problem lies with the Australian government and with the people who vote for them. The boycott was directed against the biennale who gets money from Transfield, who only acted the way it did because the Australian government asked it to act so as capitalism invariably does. And that led to a protest maybe a little off: against Big Bad Capital, not against governmental decisions, that authorized Transfield’s mode of business.

We as a people have a tendency to toot our own horn about our good deeds. There was something in the whole boycott that I found a little disturbing. Things are complicated, nothing is self-evident, but my ability as an artist to bring goodness and clear thinking to other people’s lives will outrun all complexities. The whole boycott thing was too close to social media hysteria—participating without information, being happy for one’s own righteousness—for me to take part in that. And maybe it’s my flaw, I don’t know.

Transfield could anonymously donate 40 million dollars to a charitable organization who takes care of starving children. Would it be good or bad? If Transfield donates 40 million dollars openly should the charitable organization not take the money? It is also hard to see why the attention is against the art exhibition. Art could be rather seen as a part of freedom of speech.

I do understand the activists who want to get attention for this important subject and use all possibilities to get media attention and that is what they should do. I still don´t like to get mails where someone tells me what I have to do and think.

I didn’t sign the petition not because I don’t advocate human rights for everyone. Of course I advocate human rights. I didn’t sign the petition because frankly it was clumsy and full of juvenile hyperboles. I used to change the system too when I was a teenager shouting that police are pigs and pulling off hood ornaments from Mercedes Benz’s. The world did change after that but I´m not sure it was because of me.

The sad thing is that the Sydney Biennale´s future is totally open because its support from the government depends on being funded by private money.

Nathan Coley

Born in Glasgow, Scotland

Lives and Works in Glasgow

I felt it was important to acknowledge the link between Transfield (the company making profit from a nasty policy of the Australian government) and the Transfield Foundation funding the Biennale. It was clear that the link was complicated and historical, but never the less it was real. I signed the letter asking the board of the Biennale to look at the connection, and for them to consider whither they felt it was an appropriate form of support.

I ask these tough questions of myself every week and find a way to deal with what the world asks of me.

I never threatened or offered to boycott the Biennale. Four main thoughts crossed my mind when dealing with the situation: Don’t censor yourself. Let your voice be heard. Take advice from people in Australia about this issue from their position, and finally trust Juliana Engberg (the artistic director of the BoS). I have a long professional relationship with her. She has been a supporter of my work for many years, and “eyes open” loyalty is important to me.

It pissed me off that a number of Sydney academics were calling for a boycott—asking the artists and the public to “withdraw” from the Biennale. These guys (and they were all guys), in their safe tenure positions, paid comfortably by the state, with their principled yet inexperienced students nodding to the debate. They are of course impotent but secure in their intellectual superiority.

Artists of course deal with the messy issues of life, politics and art all the time. Working with state institutions, being appropriated by a sense of national identity and representation, selling work to a museum of a country you care little for, travelling on airplanes too much, contradicting yourself by hiding behind the notion that “it’s what the work needs.” I don’t need anyone telling how I should act. I ask these tough questions of myself every week and find a way to deal with what the world asks of me.

I believe in public subsidy of the arts. The state should support what the market doesn’t. In any case, I’m not interested in giving the public what they want. I’m much more interested in giving them something they didn’t know they could have.

What comes out of the Sydney situation is two things. The glaring assumption from some Australian politicians that STILL think that culture = entertainment, and that the idea that art should be dealing with the issues such as asylum seekers which has fundamentally nothing to do with the participants of the biennale. Very alarming.

Secondly (and encouragingly) the level of debate amongst the artists was the most careful, dynamic, complex and articulate of all the discussions. That the voice of individuals with the most to lose, had the most gravitas, was for me fascinating and encouraging.

I think all artists should be political, but I think all dentists should be as well.

Hadley+Maxwell

Hadley Howes was born in Toronto, Canada

Maxwell Stephens was born in Montreal, Canada

Live and Work in Berlin, Germany

This letter is to the Working Group, the artist group that was writing letters to the board. We signed their first letter, happy to have such articulate personalities open up the dialogue with the board and establish a presence for artists’ concerns regarding the boycott. The letter we’re writing here is in response to a draft of a second letter (which, as far as we know, was never sent, due to Luca’s resignation). It is in this letter that we raise concerns about the everyday reality of the staff and local artists in Sydney and the effects that the boycott and conversation/action surrounding the boycott were having.

March 5, 2014

Dear Workinggroup dear all,

We would like to include our signatures on the new letter, however, we too would like to see an alteration to point 4 for reasons along the lines of what Sonia has brought up, based on our personal experience working here:

We have been in Sydney for over a month now. The atmosphere changed dramatically when the call for a boycott was sounded, as to be expected. For the biennale staff, this is a very complicated and depressing situation, many of the women working here who we have spoken with (95% of the working staff are women) have worked for more than one biennale and have returned because they see the positive aspects of the biennale and believe in what they are doing for the arts in Sydney and its role as a host to international artists and the exchange that thereby occurs. The work load for this group of already over-worked and underpaid employees has increased exponentially: we see many of them in the office 7 days a week and upwards of 12 hours a day. The mood in the office now is very somber, as further calls for boycotts, greater pressure from not so much the media as a rather reactionary tide of sentiment against the biennale rises all around them in bars, at schools in the blogosphere. This shift in the meaning of their labors is almost overnight for them, and so we can say with confidence that they are suffering very much from the situation, and we would do well to remember that these are people working here with the best intentions at heart and are very uncomfortable with being broadly characterized as having “blood on their hands.” It’s totally offensive and unnecessary in our opinion, and why shouldn’t we denounce this horrible accusation? We do not get the impression that they want to rebel and sound alarms regarding Australia’s immigration policies, though offering a place for their voices to be heard is a good idea as they have been living under the reality of these immigration policies for many years now and there has yet to be an effectively targeted protest. The boycott will not be effective if the concern over changing Australia’s immigration policies is drowned out by the cry for cleaner funding…for the moment here, we want to plead with you all to respect the psychic realities of this situation for the biennale staff.

Along with the biennale staff there are also over 300 volunteers who are coming under fire for wanting to participate in what they see as potential learning, supporting, and career opportunities. The choice to work in the arts is an ethical choice, as we all well know, and for many the rewards lie within a sense of establishing an ethics. The complexities of this particular biennale should offer a exceptionally rich opportunity to examine our ethics (we include the volunteers and everyone involved at every level in this “we”). The volunteers too are under attack from fellow students, we hear of reactionary professors telling their students to boycott without actually fulfilling their roles as educators and giving the students the critical tools and research methods to evaluate the situation for themselves. And so again, the volunteers are conflicted because they are really learning a lot and enjoying meeting the artists (we work with 6 volunteers, this is where our information comes from) and hearing about our/your/their positions on the biennale, the funding, and issues around artistic practice and its own powers of critique and transformation. Too much of the boycott rhetoric is failing to engage the volunteers’ curiosities and desires to learn and this is a great concern for us.

This implicitly extends beyond point 4 insofar as the overall tone of the letter, while it needs to be forceful, does tend to funnel the negotiations towards a boycott mentality over other forms of protest or engagement. We also have been engaged in conversations here with artists and there is considerable anxiety about feeling bullied, coerced or excluded by the call for boycott and by other artists in the process of creating this exhibition as a whole. This is inevitable, but we again would like to strongly point out that in the desire to persuade participation in the promotion of these very important and far-reaching issues that concern the support of artistic and cultural events, there are many artists that feel at odds with the force and process by which things are moving. There are as many ways to respond to this particular call as there are artists and we appreciate your attempts to maintain the possibility for this variety in the way you word the working-group letters.

We would like to sign the letter if some of the language can be altered (as indicated above), please do count us in. It is important to raise these issues, and we’re grateful to the authors for your considered and thoughtful articulations. We simple want to remind all of you that there are specific realities that are affected by generalized ideological battles.

with respect,

Hadley+Maxwell

Ane Hjort Guttu

Born in Oslo, Norway

Lives and Works in Oslo

I think what happened was important, and can become even more important as we see the results of it. It amazes me that these situations don´t occur more often, as we know that so many larger art institutions have dubious connections with various corporations. The Sydney situation actually gave me some hope, even if we don´t know what will come out of it.

I signed the joint letter to the board, which about half of the artists signed. I considered withdrawing my work. But I actually didn´t believe that any such action from the artists would be listened to, and it felt like the artists had a hard time agreeing to a common response. The decision whether one should withdraw or not was thereby left to each artist, and for me, in Norway, and with very little contact with the political situation in Australia, it was difficult to go for it. When the Danish artist Søren Thilo Funder came up with the idea of presenting a political statement in connection to his work, expressing his opposition to the Australian refugee policy and to the Transfield´s sponsorship, I decided to present a similar statement in the beginning of my films.

When Luca Belgiorno-Nettis resigned his position, I felt that the biennial board actually had responded to the artists, and done what was demanded in our letter.

It is crucial for art events like this to look into the policy of their sponsors and inform their participants. Perhaps they would have to downscale. They should look critically into any funding, also public funding of course. However, I don´t agree with the often heard conservative argument that to refuse funding from unethical corporations, should automatically imply refusing funding from a state with unethical politics. Public funding doesn´t function as commercial advertising. And: such a demand for consistence is disabling; that is; it would force us to accept almost anything or nothing. Public funding comes from the tax payers, and to me, this is easier to accept than money earned by mandatory detention camps. That said, everything depends on the context and situation: One has to consider if an art event actually makes controversial politics look acceptable, or whether an eventual action would have effect.

Søren Thilo Funder

Born in Copenhagen, Denmark

Lives and Works in Copenhagen

I was first of all very affected by the terrible reality of the individuals in the camps and horrified by the recent outbursts of violence there. I condemn the inhumanity of mandatory detention of asylum seekers in Australia, as well as anywhere else in the world, and want to express my deep concern with cultural events sponsored by companies that are knowingly suppressing basic human rights. No matter what paradoxical or incomprehensible situation I might have found myself in leading up to the biennale with this new troublesome knowledge, it was completely overshadowed by the hurt and inhumanity experienced by asylum seekers in mandatory detention. I was somewhat lifted, though, by the feeling that the concerns of local activists actually managed to create quite a spark for an extremely important debate that I am sure will not end in Sydney. I think many very wise, necessary, and honest things were expressed in the long series of correspondences between several artists that I participated in prior to the biennale. I have made it clear that I respect and support all decisions made by artists—whether that is withdrawal or participation. The fact that Luca Belgiorno-Nettis left the board did signify a change, but am reminded that the money was still in the event and even if that sponsorship ends it does not end the ill treatment of asylum seekers. Luca Belgiorno-Nettis chose to leave the Biennale, not his relation to Transfield. (I say this knowing the complex business networks that might not make such an action easy, but it still proves where the values are, I guess.)

I do want to be careful about congratulating the artists’ actions too much, be it threats of withdrawal or the promise of actions from within the show. I do hope (and believe) that it was the activists fighting for the rights of asylum seekers, as well as the recent extremely tragic events in the camps, that moved things to come to this outcome. There is still so far to go in changing policies and the reality is still so enormously tragic that I find it hard to celebrate any real victory. I hope that the changes that are coming about here will resonate into the future and into government policies on an international level and in the international art scene as well.

It is time to be on guard and protect an ethical relationship to the finances that flow through this cultural field and have a tendency to counteract the political and humanist ambitions of contemporary art.

I did not withdraw my work from the biennale. Partly because of the work I put into this and my utmost respect for the work of Juliana and the biennale staff (also in how they have handled this situation and the support they have shown towards the artists), and partly because I do believe that this situation offered a possibility to act, react, and engage with this critical matter within the space of art. I do believe in art—in some weird way—and its possibilities to engage and exist inside highly paradoxical situations. I believe in a multifaceted approach to the complexity and urgency of fighting oppression in all guises. I signed the open letter to the board. I requested a statement to be included next to my works and to begin my scheduled talk reading this statement. After the withdrawal of Luca Belgiorno-Nettis from the board, my statement seemed misplaced since it was directed at this link exactly and I chose to withdraw the specific statement. I still believe though that the critical position of ethical financing of art events is completely relevant and I hope that we will find ways to further elaborate on the situation we found ourselves in as artists very soon.

I hope that the events and debates revolving around this year’s biennale in Sydney will resonate even further and start many debates on this pressing issue. I am not against private sponsorship per se, though I do find that a complete reliance on this would be fatal for the vitality and independent character of art, but I do think it is time to be on guard and protect an ethical relationship to the finances that flow through this cultural field and have a tendency to counteract the political and humanist ambitions of contemporary art.

Meriç Algün Ringborg

Born in Istanbul, Turkey

Lives and Works in Stockholm, Sweden

I found out about Transfield’s operations and the ties to the Biennale of Sydney a month or so before the show was supposed to open. A lot of my time and energy during that month was dedicated to trying to figure out how to respond to the situation. There were extensive email conversations joining several of the participating artists but it proved very difficult to act as a group. We did write a letter, which I signed, demanding the biennale sever its ties with the sponsor, but it received a very weak response from the biennale. Looking back, I think it would have been more meaningful and powerful if we had asked the sponsor to cancel their contract with the government, rather than asking the biennial to cut its ties with the sponsor. The entire discussion could have been less about arts funding and focused more on governmental policies with regard to asylum seekers and immigrants. We could have made more of an impact that way, as people tend to have a more unified opinion regarding these matters than exhibition funding. It’s water under the bridge now.

Personally, I have never been to Australia before and unfortunately I didn’t know much about their politics. So instead of withdrawing I believed it would mean more to go there to get a better understanding of the situation and figure out what I could do there, rather than via a string of statements beforehand. At the time, I thought that as artists with creative minds and holding some sort of capacity of bending rules, we were acting too politically correct and well behaved with press releases and public announcements and I thought I could perhaps try to take another approach. I wanted to make my piece and act like everything was according to plan and then the day before the show opened take the books back to the library and leave an empty shell of an installation without informing anyone. It was what I felt I could do in terms of “withdrawal”—to not forewarn the biennale and therefore not give them time to rectify or correct my absence but instead really be a void taking up space in the show. On my layover going to Sydney, I found out that Transfield had cut ties with the Biennial (later I noted that it wasn’t the other way around). This created a kind of a breaking point in the midst of a very tense situation. Emails stopped and people relaxed, including myself; even some of the withdrawn artists returned. Now, I think this was a strategic measure by the board of the biennale to make sure the biennale would happen without disturbances, and I guess one can say they succeeded. At least, I made my piece as it was intended.

We’ve come to a point when people risk their lives to reveal secrets. The argument for which is most often ‘people’s right to know’, which both Snowden and Manning for instance cited. My partner, who is a PhD researcher at the Goldsmiths University writing his dissertation on knowing/not-knowing, secrecy and invisibility, brought this up. And it’s intriguing to think about the term right to know. Because as artists part of an exhibition, what do we have the right to know? What he has proposed runs along the lines of transparency-acts where, for instance, if an artist requests it they should be given the budget of the exhibition they are asked to participate in, and here it would be detailed where the money comes from. Because as part of their “participation,” don’t artists have a “right to know”? This may seem quite provocative to institutions and other exhibition makers of which many will probably say that it isn’t practically feasible. But I think this kind of transparency could bring these sorts of problems to an end. Moreover, speaking to other artists in the Biennale it was also obvious that some received better accommodations, better fees. It’s no news that this kind of monster art events’ funding is difficult to manage. And you have to give credit to the people who make these large art events happen. But at what cost? Wouldn’t it be better with less participating artists with more decent working conditions—for both them and the staff of the event? Perhaps you don’t really have to have six opening parties where alcohol flows like there is no tomorrow? Wouldn’t it be better to prioritize other things instead? But who am I to talk? I haven’t seen the budget.

Charlie Sofo

Born in Melbourne, Australia

Lives and Works in Melbourne, Australia

The mood and tone of the Biennale was affected by the dialogue and debate happening around and inside it. But this is what occasionally happens with art, it becomes a cypher or arena for debate. The only difference here is that the controversy wasn’t restricted to one artist or artwork but to an entire institution. Personally, I wanted to hear from the community; my peers, artists, academics and organisations like RISE and Beyond Borders. We participated in public meetings and forums, and spent inordinate amounts of our time researching the issue. While I think it was a bit difficult, it was by no means an impossible situation, we all had to make decisions based on our knowledge and understanding of the situation. Likewise, each artist had their own specific circumstances and their own specific cultural / geographical / ideological differences. The negotiation of these differences was fascinating.

A lot of my views are already in the public domain. There were many processes that led to my decision. Corporate sponsorship is about endorsements, and artists in the BoS are in the position of providing cultural capital to the Transfield brand. When debate began about Transfield’s involvement in some of Australia’s most shameful border policy, the Biennale become a test case for a divestment campaign. And so whether you believe that the connections between Transfield, the BoS and Nauru and Manus Island detention camps where legitimate or not, it was impossible to ignore the potent symbolism of the situation. Exactly how the artists and BoS board conducted themselves were important, it was an opportunity to set an example, to break the silence and make some noise about the plight of asylum seekers.

I remained out of the event because I didn’t want to bury the history of the protest. I felt that consistency and steadfastness were important. Transfield’s withdrawal seemed like a sombre victory – a pragmatic choice perhaps. I’m still processing the events and still hoping that the campaign gathers momentum.

I think we need a stronger and better funded Australia Council for the Art. The Biennale is principally funded by the Australia council, which is actually a modest amount in comparison to the 60 million dollars it returns into the local economy. Many overseas artists also bring in state arts funding from their countries of origin. The Biennale is free because it has already been paid for by everyone, and for cheap too.

I did wonder, though, how a debate in the media about Australia’s border policy turned into a conversation about arts philanthropy. Maybe this indicative of another problem? The events of this year have put a lot of things in perspective. Let’s wait and see how things develop.

Rachel Friedman is the author of The Good Girl’s Guide to Getting Lost: A Memoir of Three Continents, Two Friends, and One Unexpected Adventure. She’s written for The New York Times, BUST, Creative Nonfiction, and others. She’s a contributor to The McSweeney’s Book of Politics and Musicals and The Best Women’s Travel Writing, Volume 9. She tweets @friedman_rachel.