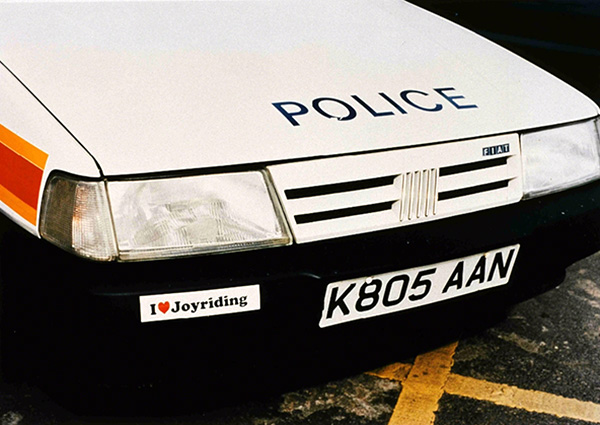

90.2 × 129.5 cm. © Jeremy Deller. Courtesy the artist and Paul Stolper Gallery.

I was in a patrol car in the rain during a siege with three violent, glowering adults—my fellow officers—in whose presence I felt almost ceaselessly unsafe, positioned outside a weatherboard house in which a distressed and armed father in his forties had fatally disciplined his child and barricaded himself inside. Gridlocked cars honked in the distance and the house cast a single long shadow across the empty trampoline and the summer brown of the unwatered lawn. In my mind, this was the day it started, though it could have been others.

Apart from the weirdly high percentage of the female population who fetishize men in uniforms, the joy of irresponsible driving, and the childlike thrill of chasing people on foot (in real life, nobody ever stops to fight mano a mano, and worst case you simply shrug and say, “He got away”), I hated the job. I hated the chilling look on children’s faces during domestic disputes; I hated the potluck of dragging a river; I hated the chore of finding bodies carbonized in clandestine meth labs; I hated Tasering and spraying and bludgeoning and cuffing and detaining and hauling and warning and fining and arresting and patrolling; I hated dying bikers who seemed mostly afraid of an effeminate death; I hated examining four-wheel drives with bits of infant skull on the tread; I hated interacting with sad people whose will to live came only from scratch-lottery tickets; I hated having a controlling interest in the short-term destinies of street prostitutes, hash dealers, and tipsy drivers; I hated serving apprehended violence orders to husbands and seeing the angry confusion of feared men who did not feel frightening; I hated how hard it was not to succumb to a bribe here, a confiscated gram of cocaine there, and the fact that despite a visibly displayed baton, canister of pepper spray, and loaded gun, I couldn’t patrol the streets without some civilian asking me directions; and I hated how at least once a month a superior officer would look me dead in the eyes and ask the same corny question. Like now, on the day of the siege. I had hoisted myself up in the seat with one eye on the jittery hand behind the curtain, when the old bearish sergeant, who always tried to create sexual tension when castigating female officers, turned to us and posed that familiar inquiry in a bladed voice: “SO FELLAS, WHY’D YOU JOIN THE FORCE?”

“My father was a cop,” said Constable Brock.

“My favorite aunt was murdered, and I vowed to dedicate my life to making sure that the scumbags of this earth get the justice they deserve,” said Constable Miller.

“What about you, Constable Wilder?”

What could I say? While most cops are in bullied-in-revenge mode, or pious bad eggs with dreams of deadly force, I’d come here by way of failure, by way of words rotting on the vine. I didn’t want these men to know we were on competing wavelengths and they had every right to mistrust me, so I drew a blank and made no response. Policemen are excellent at staring unpleasantly, it has to be said. The lengthening silence was punctuated by the fleeing footsteps of more neighbors running for cover, and a voice over the radio asking, “Is Constable Wilder riding with you?”

“Unfortunately,” the sergeant said.

“Constable, you know an Aldo Benjamin?”

I gritted my teeth. That question was usually a prelude to some onerous task I’d be called on to perform. “Old high school mate, Senior Sergeant.”

“Swing by the station after your shift.”

And I hated—I almost forgot—I hated how family and friends would inundate you with legal questions, such as my uncle Hamish, who often probed me about drug trafficking—such as whether border patrols check hair extensions—and mates who demanded favors when they got speeding and traffic infringements, or expected special treatment when breaking the law or mired in legal jams, as my old friend Aldo Benjamin was prone to do. That afternoon, driving back to the station, I thought with increasing fatigue about how every few months, pretty much since the day I’d been sworn in, Aldo found himself in a dilemma that required my assistance: bar fight; bar fight with bartender; accused by neighbor of poisoning then running over beloved terrier; purchasing a gram of cocaine thirty seconds before a police raid; being a suspicious person, and then being a suspicious person in a vehicle; opening a car door into a bicyclist’s face. Recently, he’d called early one morning to ask if I knew the age of consent. “Sixteen,” I said. “Get dressed,” Aldo said to someone else, and hung up. It’s an open secret and practically an unwritten rule that every officer, regardless of rank, is allowed to step in and ask for special consideration for one fuck-up: a father who needs around-the-clock surveillance; a cousin who requires a security detail; a wayward mate who needs backup or bailing out. It was on Aldo that I more than used up this precious token. This was not your regular sympathetic ear or shoulder to cry on, but a new definition of friendship, one that included a little hocus-pocus with paperwork or actual armed reinforcements. Now I wanted to call ahead to the station to get a hint of what was waiting for me. It could be anything from possession to reckless endangerment, a gross misunderstanding or a bad judgment call. Some people defy the limits of your imagination and you just have to accept that.

The majority of Aldo’s sad imbroglios were related to his businesses going kaput.

I turned off the freeway. The majority of Aldo’s sad imbroglios were related to his businesses going kaput. After we graduated, Aldo grew into a serial entrepreneur and small-business owner with a knack for flooding the market with products that didn’t sell, and starting ventures that actively repelled customers. For more than a decade he demonstrated a special magic for attracting investors and losing their money, and because his repeated failures failed in multifarious ways, and because he always felt tremendous optimism for a project and then incredulity when it bombed—yet somehow managed to get back on his feet just when you’d counted him out—there were incalculable numbers of unhappy small investors out to get him, any of whom could be the cause of today’s emergency.

The chaos of those fifteen-odd years since high school passed for Aldo in an entrepreneurial blur: his retrofitted 1963 Airstream trailer food truck (it crashed), his warehouse dance parties (shut down by police), his vending machines stocked with health snacks like gluten-free flaxseed bars and quinoa cakes (vandalized into disrepair), his prototype of a device that detected trace elements of peanuts in food (it simply didn’t function), his tanning salon taxi service (customers sued for melanomas and motion sickness), his I’m Not Drunk, I Have Cerebral Palsy You Ignorant Fuck T-shirts (three sales in total), his maternity clothes for goths (a demographic with an 85 percent abortion rate). Not to mention his midlife-crisis consultancy clinic, his Mexican taco stand, his foam eyewear, his recycled soap, and his doggie dental mints and paw print art. His product launches were all teachable moments: he never knew his market, he foisted poor-quality merchandise on customers he ignored. Who were his lenders? Where did he find these foolhardy creditors? His mother, Leila, was always good for start-up funds. So was his girlfriend, Stella. Uncles. Friends (myself included). State government small-business loans. Angel investors, men with crushing handshakes—overcompensation for prior accusations of limpness, Aldo assumed—who’d take new shirts out of their thick plastic envelopes and change right in front of you. I suppose in his mind failure was unimaginable, despite its persistent recurrence. Otherwise, why would he have blown his mother’s entire retirement fund, forty thousand dollars, to manufacture fashionable sandals in China? He didn’t have excuses or explanations, he had anecdotes: how he bought inventory in bulk up front; how he arrived at the factory to find they’d made the whole lot out of a synthetic flammable material that irritates human skin; how on the way to a key meeting he was stuck in a historic traffic jam that lasted from 9 a.m. until 5 p.m. the following day; his realization that the replacement supplier’s headquarters were in one of China’s cancer villages, which he couldn’t bring himself to enter. It went on like that. I remember when he came back from the debacle, he couldn’t face Leila; he called her from a pay phone in Chinatown every lunchtime for six months, pretending he was still in Shanghai. One afternoon Aldo and Stella were in the supermarket, and who does he run into in the frozen-food aisle? The look on his mother’s face was his lowest moment, he said, and he vowed, “I will never again try to make it big in this world! I will merely subsist!”

So why didn’t he listen to himself? Two reasons. First, because Aldo was a precocious sucker of the success industry. He’d always be listening to motivational talks, lining the pockets of a succession of tacky gurus, Tony Robbins types, and once, Tony Robbins himself. He read books with obnoxious titles like See You at the Top and It’s Yours—Take It, and listened to audio-biographies of successful business leaders like Zig Ziglar and Warren Buffett and J. W. Marriott, Jr. He said things with an intonation that let you know he was speaking in quotation marks. He said: “Belief creates its verification in fact.” He said: “I’m the only asset I’ll ever have.” He said: “The prepared mind takes advantage of chance.” He said: “The secret to success is hard work.” I thought: It’s not much of a formula. The opposite is also true. Some failures work like bastards.

The second reason was Stella: while he provided emotional support and material for her music, found her rare records and allowed her to use his wilder pronouncements as lyrics, she in turn gave him strength to believe in his ideas even when they weren’t worth believing in. They were a genuine team, charmed by each other’s blather; they regularly removed fear from one another’s path and never let the other feel foolish, even when his businesses crashed and fizzled or she played some pretty bad songs in some pretty public places to raucous derision. They were an all-time great couple, one that even argued respectfully, like two nations stopping warfare to let the other bury their dead. After they divorced, I suspected it was the hope he might win her back that inspired him, each time he was ruined, to get on his feet again.

How does one distinguish between hope and false hope? How do you sell a product to anticonsumerists?

I always knew my insolvent friend was about to remount the entrepreneurial horse when he started talking about untapped markets. The aging population! Women over forty struggling to conceive! Couples with mismatched libidos! Honeymooners with creeping malaise! Insomniacs with global dread! Shoppers with ecoparalysis! Corporate bandits ashamed of their bodies! Upscale couples one set of genitals away from being totally interchangeable! Under-tens with overweening narcissism! Baby boomers in terminal decline! Rich space tourists! Face-transplant recipients! Speakers of all 6,909 living languages! That was Aldo, always trying to solve a dilemma. How does one distinguish between hope and false hope? How can one tap into the nauseating pandemic of public marriage proposals? How do you sell a product to anticonsumerists? Where should one go to manufacture clothes for obese toddlers and newborns in the ninety-seventh weight percentile?

It was the answer to the last that took him to India. I drove him to the airport, and can still remember the thick veil of fear on his face as he disappeared through the departure gates. One month later he came back with a beard and mysterious scars and monkey bites and another series of rabies shots (his third!) and even further in debt, with only scraps of information about problems communicating with the tailor, about waists too high, crotches too low. I suggested he take a break. Just get a regular job like a regular person. Three months later he opened a steak restaurant on King Street called High Steaks, but Newtown, famous for its vegans, did not bite and High Steaks shut its doors. He stopped reading self-help and prosperity literature, wanting to go deeper into the psyche of his customers, and moved on to psychology texts, both popular and academic, turning to authors like Jaspers and Binswanger and Hoogendijk and Achenbach and Skinner and Piaget and Adler and Horney and Laing. Then he moved on to reference books: the APA Dictionary of Psychology; Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders; Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology; Clinician’s Guide to Neuropsychological Assessment. He said he needed a product that would appeal to people’s solipsism, their unembarrassed love of self and abiding fondness for their own point of view. He seemed desperate to make anything on an industrial scale. Yet he had substandard luck and submental ideas: for instance, transdermal chocolates, patches that transmit after-dinner mints and dark almond whirls through the skin into the bloodstream, a product line that Time Out Sydney gave a devastating (if amusing) one-line review (a confectionary Willy Wonka wouldn’t touch with an Oompa Loompa’s dick). Aldo sold off the remaining merchandise for this last idea and came out even, which, somehow, for him, was worse than complete failure.

He said: “Often the thing that drives you crazy about failure is its proximity to success.” Still, he bore his losses uncomplainingly. If only his investors would too.

As I drove along the shadowed city streets in the convulsing afternoon traffic, it occurred to me that the only person genuinely pleased with the absurd non sequitur of my becoming a police officer was Aldo, who had perhaps foreseen how frequently he would require my assistance. This was without question the most inconvenient alliance of my life, yet at the same time there was nobody else with whom I felt the most real and relaxed version of myself. To be honest, my most relaxed version grated on Tess, and I had begun to fear there was potential for divorce in my future. And Sonja, my sweet little monster: she still worshipped me as little girls do their fathers, but that would draw to an end once puberty got its messy hands on her. And though I could always make friends, I could never again make an old friend—that time had passed for me forever.

If Aldo perceived himself as a burden, or thought he had overshot the boundaries of our friendship, he had never given any indication.

And yet I didn’t flash the light or put on the siren as guys on the force all sometimes did to slip through heavy traffic, because, I realized, I was reluctant to come to my old friend’s rescue yet again, or put in a good word for him, or bail him out, or plead for special consideration. Instead of hurrying, I took alternative routes, slowed down at yellow lights, let civilians overtake, felt plain relief when a tunnel under construction forced all the cars into a single lane; and when at the lights I allowed a bare-chested methadone addict to clear my windshield with a quizzical pout, I finally understood how tired I was of being immured by a friendship that was taking such a personal and professional toll. If Aldo perceived himself as a burden, or thought he had overshot the boundaries of our friendship, he had never given any indication. In fact, he had unwavering confidence that I’d always step up for him at a moment’s notice and zero qualms about pestering me with the consequences of his unintentional yet frequent clusterfucks. Although it made me his enabler (Tess’s words) I never hesitated or refused him, but even after saving his life or extricating him from whatever jam he was in, he’d only give me the bare minimum of thanks before trotting out incongruous snark, or lighthearted ribbing. Lately his troubles had increased in frequency and seriousness; I felt apprehension at seeing his name on my caller ID, and that I was being taken for granted. The cumulative effect of these favors was to tip the balance of our friendship—as failed writer and destitute entrepreneur we were in the same boat and I could laugh at his one mishap after another, but as a policeman I seemed to serve only one purpose for him and I was beginning to resent it.

At the station, I walked past the Caution Wet Floor sign that had been there for months and into the restrained chaos of three men in wifebeaters, panting, with two sweaty constables standing over them. The men sat as if tight spaces had been drawn around them, afraid to interact. I’d clearly just missed a fight. The desk sergeant stared impassively at me.

“Your idiot mate’s in there.”

“What’s the charge?”

“Wasting police time.”

“That’s not a crime.”

“He doesn’t know that.”

He buzzed me through the side door. Aldo was standing beside the Wanted posters in the unpleasantly hot and glary sun-blasted corridor. He was wearing a bloodstained T-shirt underneath his old denim jacket, his slight frame bent into a posture of slothful defeat. He was quite a sight. Prematurely balding, prematurely graying, even though, if I remember correctly, he was excruciatingly late to puberty. What a sad and narrow prime he’d had.

“Here he is,” he said. “Why do you still look like a bus driver in that uniform?” Aldo gave me something I can only describe as a knowing wink of despair. “How’s things? How’s Sonja?”

“She’s starting to save her tantrums for the most public places with the fewest exits. Tess suspects she’s using our mortification as her secret weapon.”

Aldo laughed. “Everyone always says that until you have children you can’t ever understand what it’s like. That’s just because they have no empathy, isn’t it?”

“I suppose so,” I said, stepping back. Aldo waved his hands when he talked; he was always knocking people in the side of the head and not apologizing. His existence needed room.

“Be honest, Liam, isn’t fatherhood exactly what you thought it would be?”

“No, it’s totally different.”

“Liar!”

“Just take him home!” the sergeant barked.

The truth is, fatherhood was exactly what the culture had prepared me for: near-fatal fatigue, geysers of love, the cornered feeling that comes from being The Provider. But whenever Aldo asked about Sonja, I always detected substrates of old grief and even a smidgeon of unacknowledged jealousy that fatherhood had worked out for only one of us. I was eager to change the subject before Aldo threw some awful fact in my face. (Last time, it was the epidemic of precocious puberty in seven-year-old girls.) By the time we stepped outside into an ambush of sunlight, Aldo already had a cigarette lit and was furiously inhaling, as if non-smoking laws were an inalienable human-rights violation. We leaned against my car and Aldo promised to email me a video of a blonde who had trained her pug to breastfeed. I noted with relief that in the ten minutes we had been together he had not mentioned Stella once. That was progress. I thought, Maybe his heart is finally out of quarantine.

“So you’ll never fucking guess who’s getting remarried,” Aldo said.

“You’re kidding.” This was bad news, the worst. “To who?”

“Something called Craig, one of those sub-lawyer thingies.”

“You mean like a legal secretary?”

“A paralegal something or other, yeah, one of those law careers where you’re kitty litter for other lawyers.”

“Remarried! What’s he like?”

“I don’t know much. I only met him once. He’s lived in Italy and so went on and on about how lateness is culturally superior to being on time.”

“What a cock.”

He pinched the cigarette butt so tight it became a flat wedge he had to suck hard on to get any smoke through. The air grew heavy with the smell of impending thunderstorms and Aldo told me how, the week before, he’d followed them to Bronte, down to the beach, where he saw Craig take his shirt off to reveal swimmer’s abs lodged in a soldier’s torso, and how Aldo had stood there behind some family’s beach umbrella feeling a slow liquidation of his emotional assets. He let out a dry, glum laugh, bent down to pick up a fifty-cent coin, and winced; I could see through the open shirt that his own torso was wrapped in white gauze.

“And guess what else? She’s asked me to be part of the wedding.”

“No she didn’t.”

“She still considers me her best friend.”

“Ex-husbands aren’t best friends!”

“No shit.”

We slid into the car. Aldo shifted the side-view mirror to steer clear of his reflection. We moved off into the three-lane highway and were quickly embroiled in heavy traffic.

“Part of the wedding,” I said. “As what?”

“An usher.”

“An usher?”

“That’s how I said it. An usher? An usher? So I tear the tickets in half and with a flashlight show the patrons to their seats? Something like that, Stella said, laughing, thinking that my being lighthearted was proof of her good decision. But I begged her to reconsider. I mean, first of all, I almost choked when she told me the wedding is on a rooftop. I said, ‘It’s outside?’ Her whole life she’s dreamed of getting married the traditional way that we never did, with the dress and the cake and the whole extended family, and then she goes and organizes an outside wedding? I mean, thirty-six years in the planning and it can’t rain?”

He was breathing heavily and staring into the copper light that glinted off the skyscrapers from the setting sun.

“To be honest,” I said, just to stir the pot, “I never understood what you saw in her.”

Aldo snapped to attention. “For one, she’s naturally beautiful. I don’t know if you realize this, but the whole time we were together, she never once wore makeup.”

“That’s like describing me by saying, ‘He doesn’t wear a hat.’ So fucking what?”

“So shut up and put on the siren.”

“Grow up.”

If you wait long enough in life, your jealousies will eventually make no sense.

A long stretch of gridlocked traffic, and I had to actively resist the homicidal urge to plow through it or open the door as motorcycles weaved past. As usual, civilians who pulled up beside me looked straight ahead with fixed postures, or slouched down in order to hide their texting, or rolled up their windows gradually, or all of a sudden, to contain the smell of pot. Ten minutes later, we’d only moved two blocks. Aldo eased back into the seat and put his bare feet on the dashboard. I knocked them off.

If you wait long enough in life, your jealousies will eventually make no sense. Stella’s devotion to Aldo had always nested a special envy in my heart. She adored him, beyond all bearable limits. She wrote songs about him, for Christ’s sake, songs that she performed in front of strangers. In that era, I had a few times made the tactical error of going out as a foursome; they behaved as if their love took place at a cellular level and whatever Tess and I had going on seemed—was—paltry in comparison. And now—poof!—that love was gone.

“How’s your novel?” he asked.

“I’m taking a hiatus.”

“You shouldn’t let failure go to your head. “

“You don’t understand. When I write about a character, it’s like getting a tattoo of them on my arm, and when it doesn’t work out I carry the failure of the relationship around with me forever, like some celebrity—”

“Loser.”

“The man just arrested for wasting police time is not calling me a loser.”

“That’s not how it went down.”

“What happened?”

As we stuttered along in the peak-hour nightmare, Aldo told me the whole story.

Earlier in the day, he’d convinced Stella to return to Luna Park with him in the hope of rekindling their romance, a dud idea that misfired almost as soon as they got through the turnstiles. He blurted out the whole spiel about them giving it one more shot. “She said, ‘Face it, Aldo, the marriage was a failure.’ I said, ‘Just because the relationship didn’t end with one of us dying, doesn’t mean it was a failure. Despite being the gold standard for our whole stupid civilization, my death or your death is actually a ghoulish barometer for marital success.’ Then we talked about the state of our union in those final months. She said it was rusted and leprous. She said, ‘A love drawn taut snaps eventually.’ She said, ‘Maybe our youths ended at different times, did you ever think of that?’ I said, ‘Let’s lay all our cards on the table,’ and I proceeded to tell her that somewhere affairs were had, by me, just two minor indiscretions that any competent marriage counselor would have recommended to couples staring down a commitment that stretches interminably into the future. Get it out of your system, I imagined the marriage counselor advising.”

“The imagined marriage counselor?”

“Hey, my conscience is clean: I change it every week.”

“That doesn’t mean anything.”

Aldo laughed loudly, then bit his lip as if he’d revealed something he had set out to conceal. “Anyway, I told her how deeply and permanently and profoundly hurt I was by the way she left me.”

This I knew. One night Stella had pretended to talk in her sleep in order to confess to Aldo that she was in love with another man. “Aldo, Aldo, I’ve met someone,” she murmured. She had hoped, he supposed, that he would feel as though she had left herself ajar and he could peek in when her mind was turned. She murmured, “Slept with him.” And, “Leaving you.”

Aldo recalled his own precise features, based on photographs and countless hours staring unhappily into mirrors.

At Luna Park Aldo ceremoniously forgave her, but it was irrelevant. Stella dropped the bombshell about her upcoming nuptials to Craig. This hit him hard. They stood like two mutes; he felt like a removed tumor that was trying to graft itself back on. He yelled into her eyes and nose—fuck you, you fucking fuck—and stormed off and wound up between the pavilion wall and the back of the Rotor, a narrow corridor that smelled of popcorn and urinary-tract infections, where he stood sobbing, for just a couple of minutes, he said, when two lean, muscular teenagers, one in oversized sunglasses, or maybe safety goggles, put him in a headlock and escorted him at knifepoint to an ATM where they forced him to withdraw, in their words, “the maximum daily amount.”

I laughed at the cold precision of that term. “What then?”

Stepping up to the bank machine, Aldo whispered to himself not to forget his PIN, and promptly forgot his PIN. The teenagers’ eyelids twitched erratically and their pupils were dilated; their brownish teeth and broken skin suggested methamphetamines, Aldo noted, and they looked to be no strangers to violence, nor to fault-finding parents, low grades, truancy, nil self-esteem, and a dissociative loss of control. Aldo thought about how stabbing was extremely high on his list of fears—to be slashed, while dangerous to muscle, would be bearable; he imagined the wound would be hot and biting yet survivable—but stabbing! That conjured up fatal thrust wounds and vascular organ damage and unimaginably nightmarish punctured-lung/asphyxiation scenarios, even less pleasant than a bullet in the stomach. (“How many movie villains have told me how long it takes to die from a gut wound?” he asked me.) “Put in your fucking PIN,” the shorter teenager shouted, and in reaction to his mind’s utter blankness Aldo was now wearing a smile that may have been misconstrued as sardonic or mocking. There was a tense silence, and other than stare into the unappeasable drug-fucked faces of youth and say he had a low tolerance for foreign metals, what else could he do? (“Besides, I think sluggishly on my feet,” Aldo admitted.) At this point, he recalled, the teenager raised his knife hand in a tight arc and brought it down at a diagonal rush, and Aldo thought, Slashed it is! with actual relief as he went down on his knees and felt weirdly vindicated that he had accurately deduced the (hot, biting) sensation before falling face-first onto the hard concrete, which, on his cheek, was sun-warmed and gravelly. A thirteen-year-old couple who had to take out retainers to kiss spotted him and called for help, and he was tended to by the skeleton staff of Luna Park’s First Aid Station, interviewed by security personnel, and driven to the police station, where he was offered instant coffee and seated opposite a sketch artist, a uniformed man so rigid and stony, Aldo said, he looked like “he would have to be loved intravenously.”

“That would be Constable Weir,” I said.

It was then, Aldo continued, that it occurred to him, possibly out of an overwhelming sense of the futility of the exercise, or the simple unlikelihood of justice, how amusing it might be to describe his own face.

“You did what?”

There followed an intense marathon as Aldo recalled his own precise features, based on photographs and countless hours staring unhappily into mirrors, and described himself with narcissistic intensity and an almost hallucinatory level of precision (lightly copper complexion, slightly acned with multiple crosswise scars; clenched, rounded jaw; chestnut-brown hair thinning to a single vertical dagger; narrow facial shape with high forehead and horizontal wrinkles; bushy eyebrows and blue deep-set eyes with small irises; off-white teeth; medium-sized chiseled nose with pronounced nasal wings; low cheekbones; large earlobes; downturned lips, with tendency to lower-lip pout and a pouching of the skin below the lip corners, etc.).

Constable Weir drew and Aldo examined and corrected and Constable Weir—despite the silently dawning realization—adjusted and redrew and grew weary of their collaboration but on the whole was patient, exact, determined not to fail. After two and three-quarter industrious hours and now with barely restrained fury, Constable Weir printed and slid the image across the desk. Aldo looked at it impassively; he felt like the exact sum of his parts, no more, no less.

“Is this him?” Constable Weir asked.

“Yes,” Aldo said. “That’s the bastard.”