It’s the first week of August and I’ve lost track of what my life is good for. Seeking oblivion, I’ve joined some friends in a rented cabin in Maine. These last few mornings, I’ve woken up around 8:30, lying in bed a little while longer and then walking barefoot with my yoga mat down a soft path of pine needles and moss to the dock. It’s a short practice, only half an hour, and by the time I’m done, everyone else has drifted down with towels and coffee mugs. The sun shines fully on the dock in the morning, and we warm ourselves a few minutes before diving in one by one. We had expected to swim despite a chill, expected to struggle, but there is none.

A long time ago, I heard someone refer to non-artists as “civilians.” And as I pass the days here, swimming and eating lobster and feeling richer than my day job should allow, fresh off the failure to publish my first novel, which took me six years to write and for which I never considered another alternative, I think to myself, Perhaps I am a civilian. And, Would that be so terrible?

*

The book I wrote was called Mikey Shine, about a small-time drug dealer who trades an aimless life in South Florida for the insular world of Chabad-Lubavitch, a messianic Hasidic sect of Judaism known for bringing secular Jews back into the fold. At a Brooklyn yeshiva for recent returnees to the faith, Mikey and the other students, all lost boys, struggle to reconcile the fraught secular lives they’ve left behind with their new spiritual identities.

Responses from agents trickled in over the course of several months. The book was too niche, too introspective, too religious. The Torah exegesis bored them. What did it have to do with now, with us? Why would a kid like that become religious? They didn’t buy it; they couldn’t relate.

I found ways to defend my honor in conversation with civilians. People only want to see Hasids selling drugs or having gay sex, I told them. They don’t care to watch them study Torah. They want to root for someone breaking out of fundamentalism, not being drawn in.

I empathized. After all, my protagonist doesn’t stay in yeshiva: his love of textual study only awakens him to the possibility of creating something of his own, and the story is revealed as an artist’s journey. But Mikey’s initial susceptibility to the poetry of Biblical text seemed to my readers a kind of original sin, and one that I was guilty of by extension.

*

I dropped acid for the first time at fifteen, and beauty burst through the thicket of my teenage dramas and insecurities like a glowing, white reindeer—earthly and ethereal, at once. Though I didn’t yet think of myself as a writer, my first trip yielded pages and pages of new insights: there was truth buried everywhere, in everything! Life split into before and after.

In a larger group of high-school druggies, my closest affinities were with those who preferred acid’s mind-expansion to the base thrills of ecstasy or cocaine—in particular, a pair of serious, brunette twins, and a capricious blond named Gabe. At some point during our senior year, one of the twins was approached at a strip mall by a charismatic Chabad emissary, a prototype of the many thousands stationed at outreach centers worldwide: Excuse me, are you Jewish? Perhaps it was the long days at the hospital, watching another friend, a ringleader of sorts, laying lifeless in a drug-induced coma. He answered yes. Soon he was going to classes a few nights a week. Soon his brother and Gabe were coming with him. It was shocking at the time, but it makes perfect sense to me now. They were primed for mysticism and scared to death.

I remember meeting up with one of the twins a few weeks into his transition, at a secluded spot where we used to get stoned. He wore a black suede yarmulke, a white shirt, and black slacks; he seemed pained as he delivered his pronouncement. “I don’t think there’s anything wrong with our friendship,” he told me. “But the Rebbe says it’s wrong to keep women as friends, and I’m doing this thing now, and I have to trust it.” He suggested we become pen pals. He even wrote me a few emails after we graduated, while I was in college in Manhattan and they were all three at the yeshiva in Brooklyn. I never wrote back.

That was all I heard of any of them for five years. Until one evening, I got a call from Gabe. While the twins were becoming rabbis, finding wives, he was moving home to Miami. He had drifted back out of that life, drawn more urgently, of late, to secular fiction than to scripture. And when I landed in Miami a few months later, weathering the Great Recession at my mother’s house, we fell quickly in love.

*

We were still in bed early on a Sunday morning when Gabe, by then covered in tattoos and playing in a punk band, got a call from the eminent rabbi of his former yeshiva. “Gavriel!” cried the rabbi, using the Hebrew pronunciation of his name. “Where are you?!”

It was a mistake; he was looking for another Gavriel. But the call unsettled my lover. He immediately recalled the story of Adam in the Garden of Eden. Where are you? It was the question God asked Adam after he ate the forbidden fruit and hid in the bushes in shame, a question understood by the sages as a call to account.

I was captivated by the way these details fit together: the content of the phone call; my boyfriend’s restive, reflective mood; God’s appeal to Adam in the garden. It appeared to me as a story, readymade. I thought I would write just that, the phone call, and that would be it. Instead, every scene opened up another. Gabe was eager to talk, and I wrote through our memories until I couldn’t tell the difference between the ones we shared and the ones he had given me, between the real details and the fictions that emerged from them. The breezy but somnolent Miami of our adolescence, our ill-fated, drug-addled friends, a true-to-life slang almost too embarrassing to record. The night after his father left, when his mother drank herself sick in the dirt of their small backyard garden. The cold, crumbling seaside yeshiva in Brooklyn, the predawn foghorns on the bay, the garbage bags taped over the windows for warmth, breathing with the wind. That day we ran into each other in the lot of a Coney Island concert venue—me, the picture of a college libertine, and him in Hasidic garb, presumably out on an outreach mission, but in truth, he said later, looking for me. And the exquisite exegetical lessons, the ones he still loved despite himself. He hadn’t known where to put this love; I was the perfect vessel. A lifetime of practicing a cultural Judaism free of orthodoxy or even any supposition of belief—of social justice Passover seders, Leonard Cohen lyrics in place of official liturgy—had left me with an uncomplicated relationship to text and ritual, a deeply felt license to swipe or recast what sparked and discard the rest. My intoxication with these ideas, these stories, these texts, mitigated the shame he felt in having been seduced by them. It gave him permission to keep what was beautiful.

The project outlived the relationship by several years. In my darkest moments, with the book and with my own heartbreak, I feared I was only writing for him, to get close to him, to remind him that I was the only one who could understand what he’d been through. I worried for years that it wasn’t my book. But somewhere between the first and second draft, with the ghost of my former love gradually diffusing, I noticed a change. Where I once looked at my character, Mikey, like a single mother scrutinizing her newborn for the features of a lost love, I now had to admit his surprising independence, and also the greater influence of my own habits and preoccupations. It was time to ask myself, what was this book about to me?

*

I admit that I’m attracted to artists and to stories about artists. In a certain sense, though it shames me, I have trouble fathoming what other people do, how they organize their lives, how they make meaning from its evident meaninglessness.

The more I learned about Chabad Hasidim, set up on American city street corners and in far-flung posts around the world—a uniformed, self-proclaimed army of truth and light—the more I identified with their spiritual orientation, their irrefusable sense of duty. The more I identified with their non-civilianness.

No story is more illustrative than their creation myth:

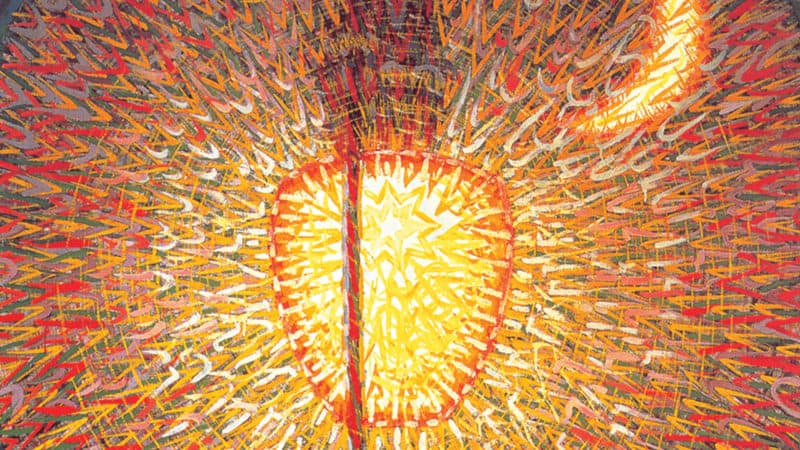

According to Kabbalist lore, to create the world God emptied Himself out, forming a vacuum of space and time, contracting into a single point of infinite energy and density. And then, in a great cosmic flash, He exploded outward in all directions.

God’s emanating light manifested vessels to contain it, but the light was too strong and the vessels too immature. They shattered. Our material world has been fashioned from these shards, which still hold the residue, the dazzling sparks of the Divine.

Hasidim have a clear vision of man’s job in this lowly world: to sift through these shards and extract the sparks of original holiness—to find God, here. This act is called tikkun, a word vaguely synonymous with “justice” to many secular Jews around the world. But its actual meaning is “restoration,” as in, restoring the cosmic order, rebuilding the vessels ever-stronger than before. One does this by recognizing the fallen sparks, elevating the mundane to a place of holiness. When a Hasid wakes in the morning, he summons God to his bed before his feet touch the ground. Modeh ani lefanecha, he says, I surrender myself before you. He notices first of all that he is alive, and he will spend the rest of the day in ritual and prayer, attaching even the smallest of experiences—the pleasing smell of an herb, the ability to take a shit with volition—to the miracle of God’s creation, the manifestation of His will.

This insistent noticing, this relentless pursuit of the divine in the mundane, of meaning in chaos: Is this not what artists do? When they record an overheard snippet of dialogue, enshrine in a still life the way light falls on rotting fruit?

To cultivate this sensitivity, this openness to revelation, Hasidim must deemphasize money-making ventures and evade other tentacles of the material world in favor of uninterrupted time—time reserved for practice, committed and intentional, day to day to day. As artists do. Mikey learns this lesson early on in his transition to Hasidic life: that practice and holiness are, in essence, interchangeable.

*

For six years, I practiced, sometimes as a Hasid, sometimes as a writer. I burrowed into the Chabad website, reading simplified descriptions of complex Hasidic thought (a perk of their commitment to outreach is that they put everything online). I bought a dictionary of Yeshivish and spent time on Crown Heights message boards to see and hear the words deployed. I watched hours and hours of lectures by eminent Chabad rabbis. I studied discourses by the Lubavitcher Rebbe. I visited his grave in Queens. I found that as long as I dressed appropriately, Chabad headquarters on Eastern Parkway was open to me, albeit just the women’s balcony which overlooked the men on the floor. Once or twice, I accompanied the twins’ wives there on holidays. They did not know about my book, though I’m not sure it would have mattered; I was a Jew who wanted to learn.

At home, I scraped together unscheduled hours, wrestling them into bed with me, where I wrote, propped up on pillows, laptop in lap. I read each of my scenes hundreds of times as I worked and reworked them. I’d spend weeks, months, on certain sections only to trash them in split seconds of insight. I trashed much, much more than I wrote. I overhauled the book in its entirety approximately five times: rewriting and rewriting and rewriting.

When I look through this manuscript now, there are ideas, scenes, sentences, turns of phrase that I like so much it’s hard to believe I’ve written them. But I have doubts about my novel’s solidity, the potency of its spell, taken as a whole. They are the same doubts I had when I was writing, the ones I dismissed as inevitable, as something to endure and ignore, but in the absence of validation, they are hardening into fact.

Perhaps it’s impossible to love something you’ve lain with day after day, year after year, alone in your bedroom, something that exists only in relation to you. What I can say for certain is that I loved, that I was devoted to, the labor. Perhaps the most significant challenge of this period of mourning has been to cleave apart these two things in my mind, the recognition and the work—to sharpen my sense of value in the latter while the former becomes more vague. Because writing the book got me out of bed every morning. It gave me a life—a life of noticing, imbued with purpose, prone to flashes of quiet joy.

*

It is said that the Alter Rebbe, the first in the lineage of Chabad rabbis, wrote a book for tzaddikim, for the infallibly righteous and good, but he burned it. What he gave us instead was the Tanya, dubbed “the book of the Beinoni,” the book of the average person.

Who is the Beinoni? He is an aspirational ideal. Though he is not among the righteous, he represents the point where perfection has seemingly been achieved—the point at which the rest of the world might say: He is a tzaddik. But the Beinoni himself knows he’s not a tzaddik, because he struggles. He struggles against an active evil inclination, against sloth and melancholy, against jealousy of others and hatred of himself; he struggles against the temptation of instant and excess pleasure, he struggles against his own pride.

The odds are against him. He is built to fail. And yet, the Tanya tells us, it is this struggle that is most interesting to God. It is where He prefers to live. Not in the soul—he is done with that from the moment after its creation. But in the garments of the soul, the parts that are forever in flux.

God prefers the struggle. It is why He loves man above all of his creations, more than the angels who have no capacity for wrong. In the end, even the righteous envy common men, because of all places, God prefers to be with them, in the muck and the slog. In the practice and the process. This is the beauty of His creation, and for us who live within it, it’s all there really is.

*

Once I realized that Mikey was a writer—that he was writing, not just narrating, my book—much of the theology I’d been collecting began to click into place. In real life, Gabe’s defection from Hasidism began with Franny and Zooey, handed to him by his mother in a vulnerable moment. Secular fiction was firmly, if tacitly, forbidden by the rabbis of his yeshiva, and I always intended for this to be a turning point in the book. But Gabe had become a schoolteacher, and it took our separation for me to lend my protagonist my own aspirations, to recognize that he would leave the service of God because he, too, would like to be a Creator.

I dove back into the text with a renewed sense of purpose. I took the lessons apart and reconstructed them in my own words, bobbing back and forth as I worked—a habit I picked up from my yeshiva boys—trying to shake loose the ego, reunite with the source.

I unspooled long soliloquies about God’s creative process, how divine light gets buried in the physical world, inspiration subsumed in the material challenges of medium. I took solace in the stories of His failures, His creation and destruction of countless worlds before settling on our own. I thrilled to see Him hamstrung by language—a bodiless, emotionless being, forced to refer to His own “hands” or “face,” His own “anger” or “mercy” or “love.” It seemed that even He who created the world with words—spoke the word “light,” for instance, to bring it into existence—was reduced to cheap devices and poor metaphors in describing divinity itself. God lives in the process! I wanted to scream it from the rooftops. I thought its value was self-evident.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe wrote that a Hasid is “someone who knows what he lacks and is concerned, and takes pains to fill that void.” This became a touchstone in explaining to myself what my book was now about, what was contained there, in the link between artist and Hasid, and what it said about how to fill up a life.

But later on, as rejections rolled in, as I heard again and again that the “Jewish stuff” didn’t land, I began to wonder if perhaps the project was suffering under its own contradictions. Because Hasids are not artists. Their theology, in practice, is wary of artistic expression to the point of suffocation; its pursuit is often dismissed as distraction, or worse, a gateway to the temptations of the outside world.

One of the twins—the same one who wanted to be pen pals—used to make music. From what Gabe told me, he still wrote songs well into his stay at the beachside yeshiva, many of them about the junkies at the flophouse across the street. The songs were good; the other boys loved them. But he was eventually reprimanded by his rebbes. He gave his guitar to a neighbor.

In Hasidism, God alone is the Creator; we are the creation. He is the author, and we are mere characters. This places the focus squarely on life as it is lived, on the experience as opposed to the artifact.

There is something liberating about this extreme emphasis on process, but there is also its inevitable endpoint: isolation and stagnancy, hostility to new thought. For if all the books that must be written already exist, and the most primary were written by God Himself, what is left for us to do or think or feel?

A friend suggests that perhaps these are the issues with my use of the word “God” and its various attendant words: redemption, prayer, miracle, and so on. To the secular, they are words rightfully regarded with suspicion. They don’t belong to us. They belong to people protesting abortion clinics, to homeschoolers. They belong to the man on your crowded subway car shouting about Jesus when you’re just trying to relax after a long day at work.

But my commitment to my writing practice has cleared that awful plate of associations by necessity, as I search for words to describe my experience—the obligation, the ritual, the supplication, the revelation—and end up in the realm of the divine. The words exist, they are truthful and precise, and therefore I must use them, with as little qualification as I can manage.

I don’t blame anyone for not being swayed, for not wanting to be swayed. It was my job to be intoxicating, to make the material as moving and exciting to others as it is to me and Mikey. In this, I am like the subway evangelist. I’ve had an experience of God—one I am desperate to give away—but the world has refused it, and I am alone. When I say the word “failure,” this is what I mean.

*

Of course, failure is not an immutable state.

I think of Cynthia Ozick, who—like an authorial Jacob—spent seven years on a book that no one saw, only to spend seven years on the next book, her first published work.

Fourteen years! Locked in the same state, her inner and outer life unchanged—a writer inside, a civilian out—with no alignment between the two.

“This is a part of my life that pains me desperately to recall. Such waste, so many eggs in one basket, such life-error, such foolish concentration, such goddamned stupid ‘purity’!” she says.

And yet, because we know her name, because we were made to read “The Shawl” as college freshmen, and perhaps delighted in The Puttermesser Papers later on, on our own, we have hidden away her story in the “success” file, we have forgotten about Cynthia Ozick, the failure.

But Ozick herself has not forgotten. In numerous interviews, she admits to never getting over the “humiliation, [the] total shame and defeat” of that experience, to maintaining, even now, a feeling of never truly being let in. At eighty-eight, she writes grandiose essays railing against the vapidity of the current literary scene and she is mocked in the pages of the Times for doing so. She’s made it, the reviewer says. What’s her beef with the literary world? She should learn to be more generous.

But Ozick remembers what it’s like to have the work and nothing else. She knows she is the Beinoni, the one who struggles, not the tzaddik, the righteous and perfect one, though it may be hard for the world who knows her name, and especially for those of us who admire her, to believe it is so.

I recently had drinks with an acquaintance of mine, another aspiring novelist, who’s been trying to publish his book to no avail. I was supposed to offer some advice, but we realized a few sips into our first cocktail that I had little to give him. He was doing what I had done—sending off queries, getting the thing read. If there was some other way, any shortcuts or tricks of the trade, clearly I didn’t know of them.

“But you’re going to do it anyway, right?” I asked. “Like, even if it doesn’t get published, you’ll still write…”

He thought for a minute. “I don’t know,” he said.

It was a gloomy encounter, to be sure, tinged by an awareness of our shared helplessness. The truth is I had a life before this failure, and it was full; its concrete elements—the job where I made too little but had my freedom, the lumpy futon more writing perch than bed—pushed to the margins of a swollen balloon of aspirations and hope. Now the balloon has popped, and the space I saved for the life I was waiting for, the public writer’s life, is simply void. Now my job is one where I work too much, and there isn’t enough time for writing, and I wake in pain from sleeping on that inherited, lumpy futon because I fear the expense of a real bed. It is the same life, the same job, the same futon, but it is no longer temporary. It can no longer be reimagined as a romantic anecdote of life before success; it is, very simply, my life. I made this decision not to build a “career” elsewhere, made it with my eyes open, and still I’m shocked by what it looks like in practice. I cannot glorify this life of process without product. It is not nearly enough.

Yet, walking home from the bar that night, I felt a touch lighter. I knew it had something to do with the surprise I felt when he said “I don’t know”—the way it sent my own unambiguous “YES” barreling up from the bright well behind or beneath or between my vital organs that some call soul. The example of Ozick’s defiant purity, paired with what I’m learning about my own, points me toward a revelation about literature itself—that if it can be said to have a soul at all, an uncorrupted essence, it is found in the failed writer, that beleaguered but duty-bound being who is doing it anyway.

*

From the novel’s epilogue, which Mikey pens years after leaving the yeshiva:

The more I work, the more I understand that the artist is a Beinoni. He is not a tzaddik; he is not a genius. Or if he is, one among the handful, good for him, but this book is not for him. No books are for him, no songs and no paintings and no dances and no plays. He doesn’t need them. And we should cease to call him an artist, because he has missed something so essential, his existence demands another word.

The rest of us, without genius, content ourselves with practice. We power the mills of our dreams with little droplets of failure. When we can’t find the right words, we put down all the wrong ones, because there is righteousness in doing and doing badly, when the aim is revelation. The revelation itself is so exceedingly rare, and yet we are not excused. In these dark times, “God” prefers to live in hiding. And in dim light, we make things: small, misshapen, and incomplete. But they shine brighter having been built from darkness, for darkness, fitted to its magnitudes. They are creatures of great ingenuity, and courage, and love.

I do the work. The work is not progress, it just is. The work does not move things, time does. I do it anyway. It will not deliver redemption; it is redemption itself, as a wayward, sputtering vehicle, arduously maintained moment to moment, day to day.

I don’t know when I realized that Mikey and I had traced the same path, that we had both gone a long way in the wrong direction to emerge years later with only a few lessons about devotion. Perhaps only at the cabin in Maine, where I meant to forget, but ended up writing.

Uncovering the parallels between religious and creative practice—the necessity of returning to it, relying on it, even without faith—drew me through the project, made it mine. But I hadn’t noticed that I’d also been writing about failure. It is inherent to the meaning of practice, it is its very condition. Yet at the time of writing, I was too deep in the process to consider it. When people asked me what my book was about, never once did I mention the word. What strange design, that in the months since my dreams for the book have been snuffed out, the best words to turn to for comfort are my own.

*

Yesterday was Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year. On the street on the way to meet a friend, just before the holy day slipped back into obscurity, I was interrupted by a threesome of boys, black hats and white shirts, black jackets and pants, the scraggly, dark beginnings of beards sprouting on their cheeks and upper lips.

Even before they asked their signature question—“Excuse me, are you Jewish?”—I knew they were my boys, the yeshiva bochers I’d lived with for years until recently. I knew they were out on mifsoyim, outreach, fanning across Brooklyn on foot to fulfill their mission. How could they know, with me in civilian dress, just how well I knew them?

“Have you heard the shofar yet today?” asked the shortest boy, presenting the ram’s horn in his hand. I shook my head no. “Would you like to hear the shofar?” Yes.

Another boy held a machzor open in front of the boy who’d closed the deal, though they all knew the rhythms of the shofar better than they knew their own heartbeats. It took a long time, longer than I remembered. The boy sometimes faltered in the strength of his blows, and it had the affect of an adolescent voice cracking. The boy holding the prayer book could barely suppress his laughter, and I smiled with him, but he didn’t know because he was obedient and didn’t look at me.

And then, Chag Sameach, they were off, and I walked toward the train on the border of the park, where other yeshiva boys were cruising in packs, each with a shofar in hand, looking to wake someone up.

I did feel awake. Things felt different, from one moment to the next. The sounds in the street, the quality of the light. Would you believe me if I told you I was brought to the brink of tears on the train by a baby bouncing on his mother’s lap? He held the entire train car in rapture.

I thought about my yeshiva bochers, and why I’d spent all my private hours with them the last six years. They are ecstatics. They see miracle and cannot keep it to themselves. But how many people, even if they happen to be Jewish, welcome their overtures? Many, many more mock and ignore them as they pass, preferring their own status quo to the rabbit hole. These boys know better than anyone what it is to want something improbable, what it is to wait. They are trying to bring the messiah, after all.

But in the meantime, they have miracle. It makes the obligation more bearable to remember that this is its origin, that this is what we work in service of, what we worship.