3.11 conjures different things to different people. To most, it’s the date of Japan’s March 2011 earthquake and resulting tsunami that levelled entire villages on the country’s Pacific coast. Some will bring up how wave damage also catalyzed a triple man-made meltdown at the TEPCO-operated Daiichi Nuclear Plant in Fukushima prefecture, forcing mass evacuations and the erection of a 13-mile no-entry buffer zone around the plant. Others will caution that these historic corollaries are far from history. Last month, as Japan marked 3.11’s fifth anniversary, dozens of art and photography exhibitions in and around Tokyo homed in on the lessons of the disaster, many absorbed by an important question. How does one rethink the future through the lessons of the past?

Japanese artist Koki Tanaka’s contribution came in the way of Possibilities for being together. Their praxis. (2015), which comprised a set of videos commissioned by and displayed at Art Tower Mito, Ibaraki prefecture (80 miles northeast of Tokyo). This project documents a retreat organized by the artist near Mito city. For six days, six strangers were invited to take a break from their normal lives and, instead, stay, cook, and eat together. During this time, they participated in workshops—making pottery, discussing theoretical passages about community and trust from works by Giorgio Agamben and Alphonso Lingis, reciting texts from environmental and feminist movements as co-participants held up banners pertaining to those movements, and entering private quasi-psychoanalytic sessions with a companion art writer. The resulting footage on seventeen monitors of different sizes, with six additional projections on walls occupied 800 square meters of gallery space. Complementary wall text provided Tanaka’s views on creating bonds with strangers. Viewing the videos took one from one character to another, listening to each divulging his/her feelings about the retreat—a format reminiscent of reality TV, albeit not the most engaging example of that genre. All 230 minutes of these videos clung on Tanaka’s opening statement: the Mito retreat was a response, a corrective even, to the supposed absence of community spirit in Japan that did spring up after the tsunami, but dissipated soon after. Never mind that post-3.11 communities not only exist, but with updated manifests. Five years after the tsunami, people are knee deep in testing irradiated food and water, and kids for thyroid cancer, prosecuting the three indicted heads at TEPCO (yet to claim responsibility for the meltdown), and rallying for rightful compensation. Not to mention battling for a nuke-free Japan.

In architectural circles, the community center has come to exemplify an incomparable example of physical and spiritual resurrection through communal means.

Even if we disregard these facts, it remains utterly baffling how the Mito retreat actually bolsters post-3.11 Japanese social consciousness, which is the project’s ostensible aim. One cannot but think that the mismatch between what Tanaka claims and what the artwork portrays must connote some variety of conceptual sophistication in the art world. Consider how a similar slippage won him the Deutsche Bank 2015 Artist of the Year award, in appreciation of work that critic Britta Farber observed, “has its finger on the pulse of our crisis-ridden age.” Farber’s reference was mainly to Tanaka’s videos shown at Venice Biennale 2013. One showed nine hair stylists performing one haircut. The other showed five pianists at UC Irvine trying to write one score. Both were positioned as thematic complements to Japan’s post-3.11 exhibit at Venice Architecture Biennale 2012, which took place the previous year. Entitled Home-for-All, Japan’s architecture exhibit documented the acclaimed community center built in the tsunami-devastated city of Rikuzentakata, Iwate prefecture. In architectural circles, the community center has come to exemplify an incomparable example of physical and spiritual resurrection through communal means. This is partly because it was built using local know-how and materials. If one keeps these details in mind, and now returns to Tanaka’s Venice videos, one might appreciate why mere association with Home-for-All constitutes a significant achievement for the artist. It suggests that Tanaka is the art world’s equivalent of post-disaster social concern, a reputation he would have had to take seriously in order to slander 3.11 political activism as coyly he has done. Here is a quote from the Deutsche Bank award catalogue: “Art is always slow. Political action is a quick response but art is slow, it takes time. But at the same time it lasts longer than immediate action.” This from someone who went on to pick six subjects (people in the arts and a Japanese man troubled by his feisty French wife) to bond in scripted, artsy skits and soul-searching sessions for less than a week, and then proffer the footage as community building after 3.11.

Elsewhere, at the prestigious Mori Art Museum, more piggybacking on the 3.11 boom. Self-styled superstar Takashi Murakami’s exhibition The Five Hundred Arhats (2012-15) showcased four enormous canvases, 100 meters across, if laid side by side. Arhats refer to the Buddha’s most enlightened and dedicated disciples who assembled at the First Buddhist Council held in India in 543 BCE on the master’s demise. Their role in Murakami’s bridge to 3.11 has a nominal art historical precedent. Murakami’s arhats were created as a tribute to the state of Qatar, among the first nations to offer Japan aid post-3.11, and modelled on 19th century Kano Kazunobu’s hundred painted scrolls called The Five Hundred Arhats (1854-1863), most of which were painted after the 1855 Great Ansei Earthquake, whose epicenter was near Tokyo. At the Mori Museum show, an ancillary bay displaying Kazunobu Scrolls 21-22, borrowed from their home in Zozoji Temple, Tokyo, underwrote the connection. This pair contains hell-themed scenes portraying the arhat’s miracles as they rescue lost souls from hell’s tortures, their freshly-minted mnemonics—such as earth and spewing fire—probably deriving from the 1855 Ansei earthquake. No doubt the Kazunobu preface was meant to cast Murakami’s treatment of the arhat figures—sinuous lines and shivering silhouettes—in light of Kazunobu’s fluid draughtsmanship, itself affiliated to pre-modern Japan’s most revered Kano school of painting (1500-1800). Yet the shoddy, pixelated outlines of Murakami’s many flamboyantly large arhats indicate they were conceived small and digitally scaled up to occupy a vast space. Moreover, the compositions are also an inexplicable mishmash of weird gooey creatures and sporadic Chinese mythological characters with no recognizable relation to each other or with the historical arhats, let alone 3.11.

In contrast to the art world’s offerings, four standout photography exhibitions in Tokyo showed that being sullied by 3.11’s ground zero dirt was not such a terrible thing, especially if it helped combat stock images of anonymous suffering that fed an insatiable appetite for horror during the days after 3.11. Five years since then, organized by veteran photojournalist Kenichi Shindo, was displayed in the lobby of Bengoshi Kaikan, a building that houses the Japan Federation of Bar Associates in Tokyo’s government district. Over one hundred images spanned five years, largely across tsunami-hit prefectures, most by Shindo’s peers in news services, and a few by tsunami victims. Hironobu Nozawa’s photograph marked two days after the tsunami, when the waters had receded. The location is Minamisanriku, Iwate prefecture, a town the tsunami swallowed whole. A man in protective gloves weeps over his wife’s corpse. She was a caregiver for old people. Ugly and gritty, the point of view shot in natural light is decidedly unsentimental. A kneeling escort comforts the man as he laments his wife’s choice to evacuate her patients instead of saving herself. The frame lobs off the second escort, highlighting that tragedy might be immediate in its visibility but is only partially accessible. In contrast was Toshio Fukumoto’s Tokyo supermarket illustration. Pointed sideways, the camera seems distracted by the sight of an old woman. She is peering at a sign explaining the absence of food and bottled water due to the earthquake. The confused octogenarian shopper and bright colors—pink signs, a red basket, a smattering of green food—certainly make for a droll vignette. Though its dialogue with adjacent images is also a painful reminder. Tokyo was safe, even though not 150 miles northeast a meltdown was underway.

Grim but inventive, Meguro Art Museum’s experimental offering put it among the more memorable outcomes of 3.11’s fifth anniversary. Entitled Kesennuma and the Memory of the Great East Japan Earthquake, the exhibition assembled photographs taken by employees of Rias Ark Museum which is located in Kesennuma city, Miyagi prefecture. The museum was one of few city structures that escaped the tsunami due its elevation on high ground. As the waves came in, Rias Ark Museum employees watched Kesennuma city razed within minutes of the first onslaught—leaving 800 dead and over 2,000 missing. This experience has translated into a permanent collection documenting Japan’s history of tsunamis and the way they have changed the country. An important photographic segment from that collection was brought to Meguro Art Museum.

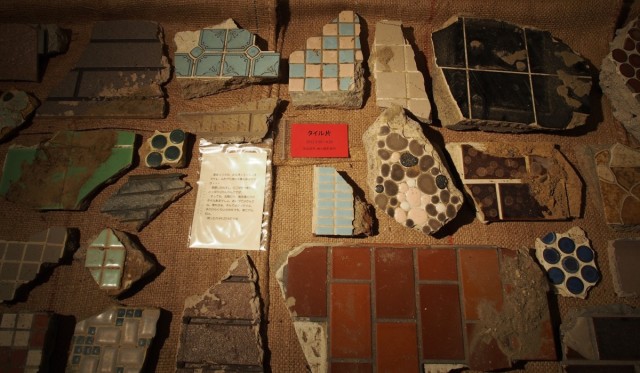

In the display, photographs were organized into two clusters: straightforward documentation and images of manipulated relics. If the first offered scrupulous views of carnage in the days after the disaster, the second demolished the common cant that visual records of 3.11 exploit their subjects in voyeuristic ways. Group two was initiated in late 2011, when Rias Ark Museum employees began collecting, archiving, and photographing recovered objects belonging to unknown people. Captured solo and in the dark, each object is lit by a single light source, lending the impression of something discovered in the dark purely by accident. The caption to each image contains a fictional impression of the photographed object through the voice of an invented character. For instance, the caption for a picture of broken multi-colored tiles remarked: “The tsunami, it carries everything away… All that’s left are the foundations. You can’t tell whose house this was. But in the genkan (gate) and entrance there’s always tiles, and that’s how you know. That’s how I knew, even if it was just a fragment… It’s still one’s home…” Devised nostalgia also brimmed in the caption for a picture of a foot pedal sewing machine: “I bought this one in 1960…I made dusters and rags with it, but I also made skirts and blouses. By the time my second son was three years old, he would get on the pedal and play on it. Eventually, it stopped working… My husband said, throw out the old one, but how could I. It’s connected with memories of my kids…I don’t mind if it just serves as a table. To me, it’s a treasure.” Repeated multiple times, this strategy produced dozens of diverse fantasy biographies that seemed to repopulate Kesennuma, letting it rise as a living character, suggesting that its devastation is an alien state.

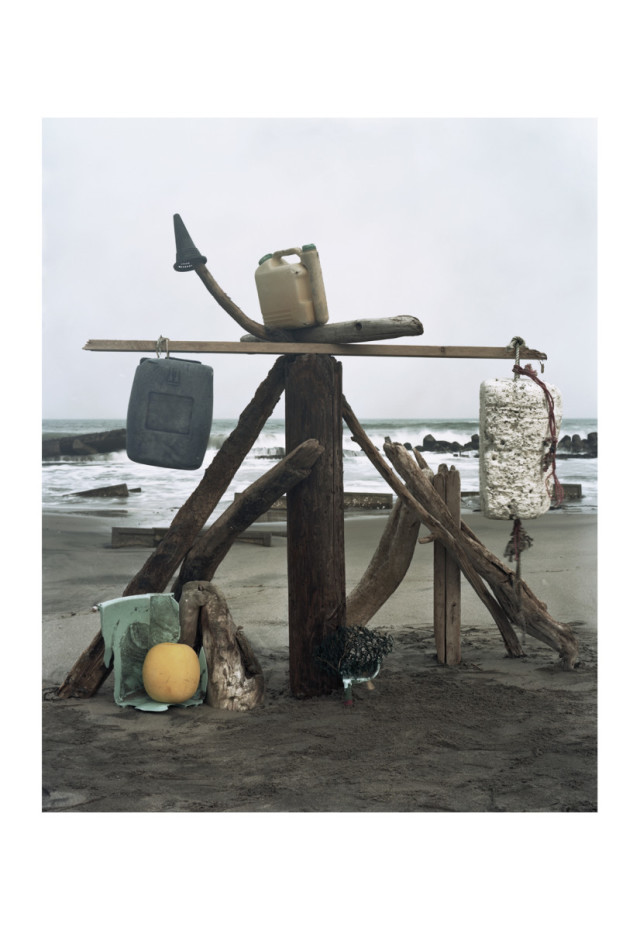

Due north in west central Tokyo, photographs of reconstructed debris engulfed the tiny, bedroom-sized Photographers’ Gallery. Kota Kishi’s 100 postcard-sized portraits in GARECKI Heart Mother presented sculptural objects the photographer constructed out of things the tsunami had washed up on the sand. Hence, the title’s garecki, Japanese for ‘wreckage’. All the sculptures were made and shot on different beaches in Fukushima prefecture in 2013, all from a straight-up frontal angle common in conventional portraiture. Except here the subjects—part-ludic, part-dour—were assemblages made out of driftwood, buoys, cans, wheels, heavy rope, boat hulls, and fishing net, among other things. In each case, the place and date collectively name the picture.

For like the show’s other images, this too suggests that recycled wreckage has its uses, especially to those with an appetite for irony.

Haramachi, 17 June 2013 instantly caught the eye. A rich red but muddied length of fabric is draped over a pole, itself propped between some fat driftwood and a plump buoy. The rather self-important contraption dominates an empty beach. Is it a totem? Is it the Grim Reaper in strange disguise? Neither question answered, one wonders if it is in fact a joke, because there really is no one to lord over except for the stone-kissed sand and some tetrapods in the distance. Then there was Odaka, 17 April, 2013. Think of it as a balancing act of light and heavy parts, including styrofoam packing and empty gasoline cans taking a playful swipe at the banality of the horizon line. “How fun this is, being united with other broken things, looking so balletic, so colorful doing it,” could well have been this sculpture’s caption. Similarly lighthearted was Namie, 5 September 2013. Three globular buoys nestle in hard laps of wood. Their pneumatic forms would be characterless but for the netted wigs Kishi has made them wear to comic effect. The trio could easily pass for an oafish family come to watch the sea, vying for space on a tiny bench at the seafront, each person so positioned that a single shove by one or the other would send them all rolling off. It is impossible not to chuckle. For like the show’s other images, this too suggests that recycled wreckage has its uses, especially to those with an appetite for irony. Because no matter which side of clownish or grisly the sculptures favored, no matter how diverting the show they put on, that they all looked a little worse for wear trumped everything. And that might be the nub of it. Are these sculptures, far from creating new images or things out of debris, more pointedly about the human psyche, which once damaged is hardly as entertainingly reassembled? Being struck with this speculation is what makes the understated humor in the photographs well worth the risk.

Elsewhere, Yuki Iwanami’s photographs of loss were striking for their theme: hunting down the dead. They were also the closest one might come to seeing dead bodies, something Japanese photojournalists pledged not to circulate after 3.11. One Last Hug (2015) at Ginza Nikon Salon staged the lives of three parents across two tsunami-hit prefectures. First was the story of Masaru Naganuma, a man in Ishinomaki city, Miyagi prefecture, whose seven-year old son Koto was one of 78 children who drowned in an elementary school, because the teacher told them to stay indoors rather than flee. Naganuma’s essay starts with a face-off. A tiny figure stands before a monumental hunk of something seemingly risen from the sand. Behind him is an earth-moving machine with a hulking claw. That’s when you realize, this is no confrontation. The figure must be there to dig, and the hunk is a half-submerged tetrapod, scaled up from an extreme low angle, which in turn captures a state of mind. Body weight to one side, the figure scans the wet sand, perhaps plotting the next move. But to what end? After the tsunami, Naganuma looked for Koto with bare hands and a shovel. When that failed, he quit his job and joined a construction company for access to industrial digging equipment. Soon, vast areas of Ishinomaki were declared searched. Volunteers and contracted diggers left. Tireless Naganuma requested funds from a tsunami survivors group to now personally rent heavy machinery. Seasons changed. Koto’s is one of four children’s corpses still missing. All Naganuma yearns for is one last hug. This is the haunting behind the show’s name.

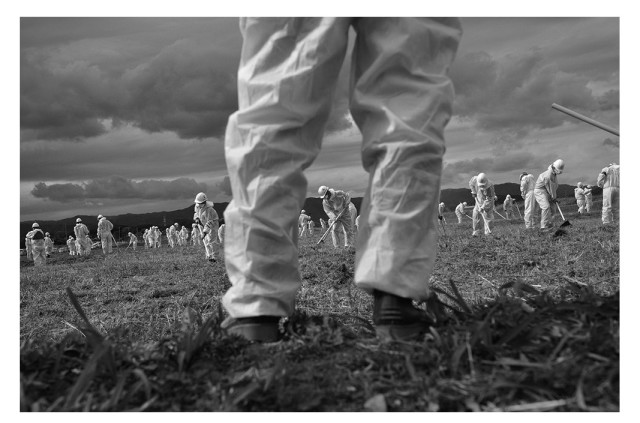

Picture after picture creates a burlesque of narrow diligence; the suited figures are focused, blind to everything but the soil, the grip sensitive to any resistance at the end of the probing tool, racing against time.

Other images in the same essay invited discomfiting thoughts. One close-up of pre-tsunami footprints, darkened by sediments brought in with the tsunami waves, hinted at escape. Is the trace a running child? Someone like little Koto? In a scene shot from the water looking at the beach, a yellow digging claw pokes its head out of the misty shoreline. It is doubtlessly Naganuma’s old friend, helping him rewrite the meaning of what the Japanese know as kasa-age. The word has always meant ‘increasing’ or ‘raising’. However, since 3.11 it routinely implies those pharaonic municipal earthworks that are rebuilding caved coastlines where the tsunami was fiercest. While merely poetic, the analogy proves at least this: that some earth-moving projects will never be about filling gaps. Rather, they are about making more to recover what 3.11 took away.

Norio Kimura in Fukushima prefecture is hardly a luckier man. He’s been looking for his second daughter’s body, jousting radiation as he goes at it. Kimura was once a resident of Ōkuma town in Futaba district, not 4 miles from the damaged Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant. Flooded and irradiated, Ōkuma was completely evacuated the morning after the tsunami. For two years after 3.11, Kimura was permitted to enter Ōkuma once in three months. Today, thirty sessions give him 150 hours in Ōkuma per year. Enter and exit. Search and abort. Trauma has a schedule, and a uniform. When in irradiated Ōkuma, Kimura must wear a radiation protection suit. For all that, Iwanami sidesteps the fear of radiation. He is far more interested in the humanitarian crises that environmental fears often eclipse. Picture after picture creates a burlesque of narrow diligence; the suited figures are focused, blind to everything but the soil, the grip sensitive to any resistance at the end of the probing tool, racing against time. One photograph shows a suited searcher, possibly Kimura, visible only below the knees, inches from the lens, standing still. Beyond him is an infantry of gleaning ranks. Fukushima has spawned dozens of Kimuras crawling the heath. They too are looking for the remains of the dead, by appointment only.

Some days after Iwanami’s show came down, memory armed with frames of Kimura’s forays into Ōkuma, I shifted gears and attended a conference organized by the Japanese group No Nukes Asia. Given the group’s anti-nuclear manifest, it was only natural they went for the jugular to mark 3.11. The No Nukes Asia Forum (March 23-25, 2016) was set in Yumoto and Iwaki towns, a few miles outside the heartland of high radiation. Location was one thing. But the event’s main success was in assembling anti-nuclear groups from Japan, Taiwan, France, Ukraine, India, Korea, Philippines, and Turkey in the same room as Fukushima locals.

The latter contingent shared this: various towns beyond the thirteen mile buffer between the nuclear plant and the rest of Fukushima are contaminated with unacceptable levels of radiation. Residents cannot afford to leave unless the government buys out their land. Their children, unable to play outdoors, are sent for fresh air to Okinawa—an island prefecture that is closer to Taiwan and China’s Pacific coast than Japan’s southern tip. Some Fukushima locals are protecting themselves with information. For instance, the Iwaki Radiation Measuring Center, Tarachine, was established in 2011 to help people measure radiation in contaminated food and water that the state claims is safe. Funded by donations that pay for ultra-modern equipment, it is staffed with scientists, and run by volunteers, including housewives, who have become what one staffer called “barefoot doctors” by necessity. Meanwhile, the government wants to market ruby-red Fukushima strawberries to up-market locations across Japan. Next year, a trick of numbers will declare parts of Tomioka, currently a ghost town, livable. Re-adjusting the level of supposedly safe radiation to just above the current count will force evacuees from temporary quarters back to wasted towns. Of course the odds of producing truly safe agricultural produce or attracting tourism to jump the economy are very very low.

Were any of the photographs at Bengoshi Kaikan or Meguro Art Museum, or those by Kishi and Iwanami so direct about Fukushima’s double disaster, or the crises wrought by the tsunami in other prefectures? No, they were not. One might have enjoyed them less, looked less carefully, cared less keenly about the ideas, were the images equivalent to a disaster report. On the other hand, one might have questioned the need for them to exist had they not engaged directly with 3.11, through communities, individuals, movements, and place that only sharpen their aesthetic curiosities. Shining through it all was a bracing, demotic view: that the intelligence of emotion, not distance, remains the most underestimated weapon in the ferment to humanize 3.11—or seek utopia through this disaster.