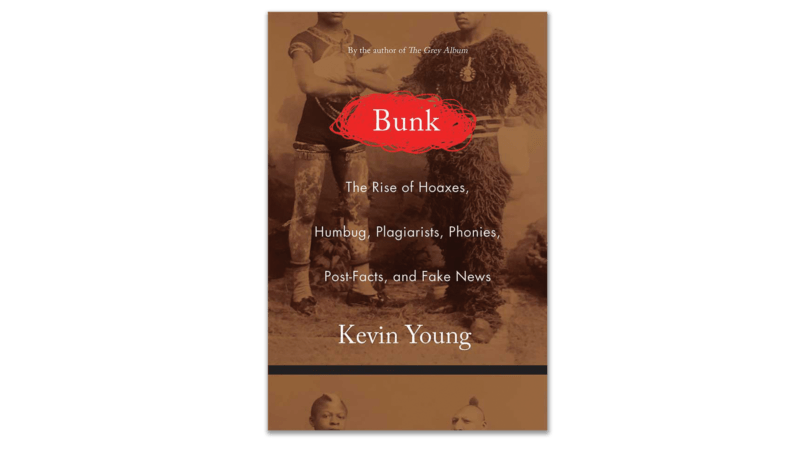

Poet and polymath Kevin Young’s newest book, Bunk, unites a history of “post-facts and fake news” with sociocultural analysis, rumination, and literary criticism. It is also a diagnosis of America’s present condition, which, to borrow Young’s words, is one of “forced forgetting in which the most immediate facts are displaced and denied in favor of older ones that claim a long neglected past, a newfound Neverland.”

Bunk chronicles hoaxes and humbugs around the world, paying special attention to that font of fakery, America. Young tackles the Great Moon Hoax of 1835, Spiritualism (a movement, originating in the 1840s, which seeks to contact the dead), a slew of fake memoirs and forgeries, plagiarism, imposture—and all related crimes. Some names may be new to readers (George Psalmanazar) while others will be painfully familiar (Rachel Dolezal). Clear-eyed and thorough, Young is both scholar and judge. Psychology can be explanation but not exoneration. Truth, facts: Young insists that these are vital, real, and important. It’s impossible not to think of Donald Trump when reading Bunk, though Trump’s appearances are limited. Young reminds us that Trump is not a liar, or not only a liar: “Liars often lie to escape getting caught; the hoaxer lies as a form of escapism, all the more pernicious in that it pretends to be real. Bunk doesn’t care if it’s real or not—it just expects you to accept it.”

Perhaps the defining character of Bunk is nineteenth-century impresario P. T. Barnum, a real Trump antecedent, minus the presidency. Barnum was a notorious showman, the man “who first turned the American invention of the confidence man legit.” He exhibited Joice Heth, an elderly black woman, as the childhood caretaker of George Washington. Barnum claimed that she was 161 years old. The American people participated willingly in their own deception: Barnum’s hoax was wildly popular, and outlived even Heth. Barnum had her autopsied in public to establish her age. When she turned out not to be 161, he simply said that he had given the coroner a different woman’s body. Barnum—like many other purveyors of fakery—hoaxed history, inventing and erasing simultaneously. His exploitation and abuse of Joice Heth’s body is no outlier in Young’s catalogue. America’s favorite deceptions are often attempts, conscious or not, to establish white superiority and innocence, whether by fabricating spurious “race science” or a society on the moon with a race-based hierarchy from a white supremacist’s dreams. As Young writes, “operating in the gap between what we wish and what we fear, the hoax renders rumors real.”

Young’s other work of nonfiction, The Grey Album: On the Blackness of Blackness, combines history and criticism in its exploration of black American culture. He is also the author of ten collections of poetry (the most recent, Blue Laws: Selected & Uncollected Poems 1995-2015, was released in 2016) and the winner of numerous awards. In 2016, he became the director of the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, and this month he will replace Paul Muldoon as the New Yorker’s poetry editor.

—Elisa Gonzalez for Guernica

Guernica: What led you to the subject of hoaxes? How did your vision of the book change, especially as you neared the end and encountered figures like Rachel Dolezal and, obviously, Donald Trump?

Kevin Young: I began it five or six years ago. In a way, I was thinking about my previous book of nonfiction, The Grey Album, which itself was thinking about the good side of lying, lying as improvisation, and tricksters. I was looking for what I called a unified theory of black culture. But when I started thinking about fake memoirs—which, it seemed, were being revealed week after week—I then started thinking about the bad side of lying and the ways in which we readily believe the worst about each other. And that got me thinking.

So then I started Bunk in earnest. It went from being what I thought would be a shorter meditative piece to what it is today, which is some history and a kind of philosophy of hoaxes. I was really trying to understand hoaxes and where they live. It was important to me to track them down in their original forms and not to rely on what people say they’re about. Instead, let’s think about what they’re actually about.

Guernica: Do you think hoaxes have gotten worse? We often hear the phrase “now more than ever” in relation to the Trump presidency and the time in which we live. Do you think there’s a “now more than ever” with hoaxes, an escalation in this “Age of Euphemism,” as you call it?

Kevin Young: I definitely think there are more hoaxes now—and they’re worse. So I think we’re in a particularly bad phase for them, which is something I started out thinking, but it’s worse than I even imagined. Someone, CNN maybe, declared the Year of the Hoax a few years ago, and it’s way worse now than it was then. There was a fact-checking or debunking web feature—through the Washington Post, I think—but they discontinued it. Not because there weren’t many hoaxes, but because people didn’t seem to care what was true and what wasn’t.

Guernica: You write about how hoaxes reveal the deep-seated cultural darkness, or anxiety, or sickness at the core of a society. What do you see revealed about America today?

Kevin Young: I think a lot of our hoaxes are about race, and about our difficult questions around race or other social divisions, but race seems to be one of the most prominent. Even something like the many wars in the Middle East yielded many, many hoaxes—everything from someone writing a fake memoir about Jordan and getting the direction the Jordan River flows wrong, to the Gay Girl in Damascus, a character who turned out to have been created by a white guy in Georgia. The Gay Girl in Damascus being unmasked as fake can turn into “The whole Arab Spring was fake.” Quickly the hoax becomes political. The thing I started to realize was that perhaps it was political all along.

The hoax used to be more positive—the news was good. We had discovered more Shakespeare, or “Look here, this person is actually connected with George Washington and she happens to be 161 years old.” But even those were fraught with questions of race. In the case of Joice Heth, P. T. Barnum’s first big success, she was black; she was, or certainly had been, enslaved, and Barnum perhaps purchased her. It quickly becomes troubling. Then fast-forward a hundred or so years, a little less, and you see some of the same troubling uses of the body and of women and black folks. That’s the way in which the hoax becomes a function of power. I especially trace that in terms of plagiarism, which I think is often not just a question of power, not just of stealing people, but of stealing ideas and stealing whole cultures and claiming them as your own.

Guernica: You come down quite firmly against the commonly circulated idea that the divide between fiction and nonfiction is thin, and that fudging the line or crossing it doesn’t matter so much. Geoff Dyer in his Paris Review interview says that it’s “a distinction that’s not sustainable.” Could you talk about the distinction and why you seem to think it’s both sustainable and important?

Kevin Young: I mean, I think it exists as a distinction. I think even most writers would admit that. I come from a genre, poetry, in which there isn’t that distinction. There aren’t “nonfiction poems,” though there are “documentary poems,” or poems that are journalistic. This is perhaps far afield, but I think your readers might think about this: a poem like “Testimony” by Charles Reznikoff, which is Holocaust testimony put into a book as a poem and orchestrated that way. I think it’s really powerful and factual and actual. If you then turned around and said, “Well, half of it’s made up,” I think we would have a slightly different relationship to it. It doesn’t mean that there aren’t structural changes or authorial or editorial changes, even in a documentary work. But that’s exactly what I wanted to talk about, because for me, getting rid of the distinction—or worse, in the case of the hoax, assuming it doesn’t exist—doesn’t recognize the hoax for what it is at its most playful. It also doesn’t recognize the power of art and the power of imagination, and the power to sometimes say things that are just totally made up! I think by saying that the line is super blurry, we muddy the waters for the kinds of achievements that our imaginative writers do all the time.

I object just as much to the ways that people go through James Joyce to create a concordance and translate all of the fictions into actual things, like, “This fictional person is that real person.” Or we do that with Kerouac—we just translate it all. It isn’t to say that these things aren’t taken from life. Indeed, in one part of the book I say, “Art plagiarizes life,” but I think we have to recognize that art has a life of its own, and life also has a life of its own. I try to respect that, and then go have fun.

I was worried a little that people would think I didn’t like autofiction. I love autofiction. It says it’s autofiction. Some of those writers are friends of mine, and autofiction is not at all a negative thing. Where it changes is a case like Jerzy Kosinski, and his notion of autofiction, which is really problematic in a problematic book [The Painted Bird].

Guernica: I wanted to talk a bit about your biography. I believe you grew up in Kansas, until you moved to the East Coast to attend Harvard.

Kevin Young: I moved five or six times before I was nine, and then I moved to Kansas.

Guernica: What was it like to grow up there? What was the transition to the East Coast and Harvard like?

Kevin Young: You know I chose Harvard—that sounds funny. Anyway, I’d lived in Boston when I was little and I had family there. So going to Harvard was actually kind of comfortable in the sense that I knew I could get away if I needed to and go to my aunt and uncle’s house, which I did. And I found good friends at Harvard: Richard Nash, whom the book’s dedicated to, and Colson Whitehead—people who are still my good friends and were important to me artistically and in life. Kansas was much more of a change for me. It’s something I write about in this new book of poems, and it’s something I’m writing about a bit more, maybe, in prose.

Guernica: An autobiography?

Kevin Young: I thought you said I don’t believe in autobiography.

Guernica: Sorry for making false claims! You’re someone with an immense understanding of American psychology who has also lived in a variety of places in the country. Where do you feel at home? Do you feel at home in America?

Kevin Young: I think I feel at home most in a moving vehicle, the most American thing ever. It can be a car or a train, just a way to cross these borders that we seem to have drawn for ourselves. There aren’t colored states. That isn’t a thing. It’s become one because of CNN or something. Having lived in many different places and having parents who came from the South, I love the American South, and I love the variety of cultures and the way that it has changed. I think that the narrative of the South hasn’t changed as much as the South has changed, and I think that’s probably also true for us as a nation. I would love us to be able to talk together, to read together, to think about the very future you’re asking me about. I hope that whatever that brings the poets and the writers will have a seat at that table. One of my goals is to try to make that table as big and broad as possible, as free as possible.

Guernica: In Bunk, I was interested in places where I thought I spotted the poet’s eye or ear: this attunement to rhyming, real or metaphorical, between words. How do prose and poetry interact for you as a writer?

Kevin Young: I think they feed each other. There’s an exactitude in a poem that is so integral to its statement about the world or about itself. In a piece of prose, the prose I love also delights me as beauty but it’s discussing something hard, whether that’s biography or cultural history or an account of Hiroshima by John Hersey, an important predecessor to some of these questions you’re asking about fact and fiction. He’s essentially writing a narrative using other people’s stories that becomes almost novelistic. I think there was no other way in that moment for him to tell that story. He’s as artful as can be. It has his hand in it; it’s not just pure testimony. But later, when someone hoaxes being a Hiroshima poet, it’s such a different state, such different stakes, when the stakes are already high.

Guernica: You’ve written on a wide range of topics in poetry and prose. You write tender poems, you write poems that take an observational eye to the world, you write poems that involve history or politics, like the one that appeared in the New Yorker about Emmett Till, “Money Road.” Did you begin writing poetry with this sense of scope, this sense of permission? Or did you acquire that later?

Kevin Young: I was writing in earnest from thirteen or fourteen, and I didn’t know there were things you weren’t supposed to write about. Writers I admire, like Langston Hughes, have such range. He has such range and he wrote lots of different things. At the end of The Langston Hughes Reader there’s a form just called “Pageant.” He’s just written this pageant [“The Glory of Negro History”].

My next book of poems will be out in the spring and it has the Emmett Till poem in it, but it also has this oratorio I wrote about a Civil Rights figure [Booker Wright]. That’s what actually helped me finish the book: writing about something slightly different than I might otherwise, though of course I was writing that because I had written the other things. The Emmett Till poem came directly out of the oratorio, because it came from driving and seeing the S-I-T-E sites down there. I really feel like the poems feed each other. The Emmett Till poem is deeply personal, and I think the key moment in the poem is when I go from talking about Emmett Till to talking to Emmett Till. That kind of movement is one I seek in my poetry. I don’t want to just talk about history or talk about music, but to embody it and address it and become fast friends with it.

Guernica: Are there strategies you return to as you write your books?

Kevin Young: What do you mean? Like booze?

Guernica: Some writers are ritualistic. They read certain writers, or they listen to certain music, for instance. When you’re in the middle of a book, what helps you to complete it?

Kevin Young: I write with music pretty much always. What I’m interested in is creating that musical quality in a book, too. When I was about halfway through what became my second book of poems, I realized that it was a double album, that I was going to tell the story of Jean-Michel Basquiat through that album structure, which helped me to give different sides. I could even start with the B-side. It gave me a bigger canvas.

I’m trying not to write books so that they’re tightly wound, but I also want the poems to hang together and tell me something more as a book than they did as a bunch of poems. I remember I had a student who handed in some work, and it was just like…poems. Then a week later it was a book. The difference was so stark. It wasn’t like it became one because of my work or anyone else’s work. It was itself. What every book wants is that chance to be its own thing.

As for Bunk, it took a lot of re-ordering. Some of the pieces were there, but to make it what it is now took a lot of time and rewriting and throwing out things and re-conceiving of its structure to start with Barnum and move from there. That used to be somehow in the middle of the book, which seems crazy now.

Guernica: Let’s talk about your non-writing pursuits. You’re about to become the New Yorker’s poetry editor, and the first black poetry editor. The New Yorker is in some ways a conservative institution, and definitely one with a lot of tradition. How will you make the poetry editor position your own, and how will you interact with that institution?

Kevin Young: I’m only doing haiku. It’s a haiku mag.

Actually, I did a panel with Paul [Muldoon] recently and we talked a lot about this. He was saying, in some sense rightly, that it doesn’t matter who the editor is, that the poems continue to be seamless. During the previous transition, I know that there were times that people thought one editor had picked my poem, when really it was the other person. What I want is to continue to explore and deepen the kind of poetry that appears there. As a reader I try to take work on its own terms. Work that moves me, makes me think, makes me laugh then cry, work that really changes my state—that’s the ideal, and there’s work that does that from all quarters. It’s such an interesting time: there’s a renaissance certainly in black poetry. In American poetry, we’re in a rich period. I’d like to explore it, but I’d also like to explore poetry in translation, and British writers, the whole array of poetry that can appear in English—or maybe it’s plural. These many Englishes that we have.

Guernica: You’re also the director of the Schomburg Center, and before that you were a curator at the Emory University archives. What has it been like getting involved in the workings of the Schomburg?

Kevin Young: I’m not sure I could have written Bunk without literal archival research. I found the cover of the book in an archive. I came to understand parts of the book through the archive, and along the way I came to create my own archive, or at least collection, of hoaxes. Coming to the Schomburg was an extension of that as a place to understand and preserve and think out loud about black culture and all its forms. That’s what I love about the Schomburg: it has art and artifacts, it has photographs and prints, it has film… There are five divisions and they’re both distinct and interrelated. Part of what Schomburg offers is a holistic sense of blackness and context. So when we do a show on black power or an online exhibition on Emmett Till, you can really see the whole of the thing that one part of the story comes from and contributes to.

I’m also really proud of the way that our staff serves that on a daily basis to the thousands of people who come through our door. We get about 250,000 or 300,000 visitors a year. We’re not a museum—we’re a place where people can come and put their hands on material and see, say, James Baldwin’s manuscripts up close. That’s really important to me.

Guernica: This is another storied institution. What are your plans for its future?

Kevin Young: Well, we just finished a twenty-two million dollar renovation, which will help us better serve patrons and have material at hand and special storage to get to that material quickly. So it allows us both to serve the material and the patrons. We’ve done this service for ninety-two years, but the renovation allows us to do it a little better. And there are these great comfortable new spaces for people.

One of my huge goals is to provide access. I want to think about how we can highlight collections so that people can understand, because not everyone has time to go through the archive. We have over ten million items and, being ninety-two years old, we have a lot of great old stuff that we didn’t just start getting recently, but that we’ve been collecting all along.

Guernica: Do you spend time with the materials yourself?

Kevin Young: I don’t have the kind of time for that, sadly. I do go out in the field still to look at some of these great collections, some of which I hope you’ll be hearing about soon. I love being in an archive, though. When I found the cover for Bunk…I was done writing, and I was looking through this box, and suddenly there’s the cover in front of me. I thought—I still lose a bit of my words thinking about it.

Guernica: Some people find Twitter toxic, some find it fun, some find it interrupts writing. How do you feel about it?

Kevin Young: I think Twitter had its halcyon days when it was filled with writers who were just realizing that there were other people doing the same thing as they were during the day. Twitter was a good way not to be isolated, since writing can be so isolating. Now it’s really different, and I’ve had to move it to the back of my phone not only because of the temptation to reflexively open it, but also a lot of the news is not so good, or it’s about the very thing I wrote Bunk about. That can get to be too much.

It’s changed, I think, Twitter, but it is a form I like. I think it’s really useful as a writer to be able to put something out there or talk about what you’re up to as a writer. I admire someone like Roxane Gay, who’s really good on Twitter. Some of the people I respect were on Twitter a lot and now aren’t as much. I miss Teju Cole, who used to do these great visual things, or little poems or prose pieces.

Guernica: I have to ask the inevitable question: Do you have advice for emerging writers, and how to survive that time of emerging?

Kevin Young: How do we survive? Wow.

Guernica: You don’t have to use the word “survive.”

Kevin Young: For me, as an emerging writer, and I’m sure for other “emerging writers,” I remember feeling that you just want to be not emerging. You want to have arrived. But in a weird way it’s a kind of magical time, to be able to be someone who is in the midst of their writing and figuring out what it is. And figuring out what it is to be a poet in the world, which is different for everyone. Emerging writers have this ability to think about some of the questions we’re all thinking about, but in new ways. They find new venues. That’s exciting.

As a prose writer I’ve had to emerge in another way. There are different timeframes: I don’t think I could have written Bunk X amount of years ago, or The Grey Album, which took almost twenty years really, and ten years of intense writing.

Guernica: Are there emerging writers that spring to mind whose work you find exciting, as poets or prose writers?

Kevin Young: Since I’m about to start at the New Yorker, I feel like if I say something then people will think I’m somehow tipping the scales. But I thought the longlists for the National Book Awards were quite exciting. There are lot of interesting people on the lists that I think people should be keeping an eye out for.

Guernica: I want to ask you the big question you ask at the end of Bunk: “What if truth is not an absolute or relative, but a skill—a muscle, like memory—that collectively we have neglected so much that we have grown measurably weaker at using it? How might we rebuild it, going from chronic to bionic?”

Kevin Young: I think the answer is the music that I mention after that. [“Funk, hokum, blue devils, the trap, the blues.”] The answer is about musical notes. I worry that we have lost that muscle, and, as I said in one part of Bunk, I wanted to write a story that wasn’t tragic. So that hope is still there for me, but…

This interview has been edited and condensed.