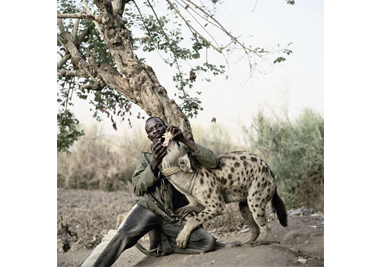

Courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York and Michael Stevenson Gallery, Cape Town

South African Pieter Hugo’s striking photographs of contemporary Africa, infamously referenced by Beyoncé Knowles and Nick Cave’s Grinderman music videos, have garnered global recognition. His work has been collected by the Metropolitan Museum of Art, The FOAM Museum of Photography, and The Museum of Modern Art. With even a passing glance at this young artist’s curriculum vitae, his influence on contemporary art and photography is clear.

Born in Johannesburg, South Africa in 1976, Hugo is a self-taught documentary photographer. His images are created using a large format camera, a bulky piece of equipment that does not lend itself to the surreptitious photographer. His work hinges on a personal interaction and connection with his subjects. “The power of photography is inherently voyeuristic,” he said in an interview with The Independent last year. “But I want that desire to look to be confronted.” And yet, he is “deeply suspicious of the power of photography.”

A question that many photojournalists and photo documentarians struggle to answer is whether a camera can capture truth. For Hugo, his work has brought to him “a type of ecstatic experience where one looks at the pictures and one experiences truth, even if it’s not the truth of an account.”

In March, The Hague Museum of Photography became the first museum to exhibit a comprehensive survey of Hugo’s work from 2003 through 2011, entitled This Must Be The Place. (The show ends on May 20.)

Publisher Prestel-Munich produced a concurrent book, Pieter Hugo: This Must Be The Place, with essays by T.J. Demos and Aaron Schumann.

Together with many previously unseen photographs, the exhibition includes a curated selection of his six published books. The most well known of which, The Hyena & Other Men (2005-2007), documents a group of performers in Nigeria and Lagos who work with hyenas, baboons, and pythons. Hugo’s Nollywood (2008) a commentary on Africa’s film industry, is described by Michael Stevenson, curator of the Gallery Federica Angelucci, as “overdramatic, deprived of happy endings, tragic. The aesthetic is loud, violent, excessive; nothing is said, everything is shouted.” Permanent Error (2011) studies a dump in Ghana where the obsession with gadget iterations—the tech industry’s “planned obsolescence”—is exposed in a narrative of global wastefulness. Although each of these evocative series asks us to reassess the perceptions of our world, Hugo’s Hague collection questions photography itself: its limits as well as its increasingly complex methods of representation.

The nature of Hugo’s subject matter has been criticized as sensational and exploitative of the “exotic other”—a criticism of documentary photography dating back to its inception. “My intentions are in no way malignant,” Hugo says, “yet somehow people pick it up in that way. I’ve traveled through Africa, I know it, but at the same time I’m not really part of it… I can’t claim to [have] an authentic voice, but I can claim to have an honest one.”

I spoke with Peter over Skype, while he was in his home in Johannesburg and preparing for a trip to London.

—Noah Rabinowitz for Guernica

Guernica: There’s a quote in the text of your new book from John Szarkowski, the important former curator of photography at MoMA, stating that “A beginning photographer hopes to learn to use the medium to describe the truth. The intelligent journeyman has learned that there is not enough film to do that.” On several occasions, you’ve said “photography is finished.” Can you talk about what you see as the medium’s limitations?

Pieter Hugo: Shoot. I think it’s important that it goes on the record that I made that statement when I was completely drunk.

Guernica: [Laughs] It is an interesting issue for a photographer to confront.

Pieter Hugo: At some stage after practicing for a while, you’re going to become aware of your idealistic intentions in the beginning and the shortcomings of your work when it gets published. For example, your intentions and the way they are being read by a wider audience are different. I guess that’s really what it comes down to. At the same time, running parallel to that, photography has always been a struggle for me to take seriously as an art form. In the process of working in any medium you become aware of its limitations. For me it was realizing that photography could only describe the surface of things. It’s symbolic. It can’t do much more than that. It’s true, seduction lies with its foot in reality. It still has the pretense of being a quasi-document. It’s something literature figured out years ago, and it’s something photography realized quite recently.

From the series Nollywood

Guernica: How do you decide what to pursue?

Pieter Hugo: A lot of my inspiration is reactionary to images I see in the media. The Hyena Men was a picture that someone took on a cell phone. Apparently he was an employee of a mobile phone network in Nigeria and he photographed them from a car window. He posted it on the Internet saying “these are debt collectors from Nigeria.”

The Nollywood series was made because while I was doing the hyena work, everywhere in West Africa—every hotel I went to, every bar I went to—people were watching these movies. At the time it really just annoyed me. It later became apparent that it was something quite amazing and worth exploring.

Permanent Error started because I had read an article in National Geographic on global recycling and there was a photograph taken on a computer dumpsite.

The Rwanda work came from an article I read in The Economist on a plane one day. It’s born from literary or media stimulation and then my reaction to it. It’s born out of something I see.

Guernica: Let’s talk about your new book and exhibition, and how they came to be.

Pieter Hugo: I currently have a touring survey show that started in the Hague Fotomuseum—the show is curated by Wim van Sinderin, and has work from 2003 onwards. There are over one hundred prints in the show and producing a catalogue for it seemed only natural. Then the catalogue became a book. The experience of putting it together was fantastic. I always have the feeling that I’m sitting around not doing anything with my life. A little Calvinist guilt that I should be more productive, but after producing this catalogue I realized that I can relax a little—I actually have been quite busy.

From the series Kin

Guernica: I’m sure it’s cathartic to put these things together and see themes arise. What kind of threads did you see while editing the work?

Pieter Hugo: This survey has been a good opportunity to sit down and look at what my work has been about—to see the different threads that have emerged, and to get a clearer sense of what my preoccupations have been throughout the last couple of years.

After I finished school I went straight into becoming a photographer, I didn’t study. In my early twenties I became a practicing photographer, whether it was commercial work, editorial work, or working as a photojournalist. There really wasn’t a space where one would get an education about the theory and history of photography. That was just something you learned along the way. There are a few major themes, of course, like “what is real?” I think that’s a big question my work poses. Secondly, it seems to provoke a lot of debate about the rights to representation.

Guernica: Your photographs seem to pose questions rather than answer them.

Pieter Hugo: I feel like I’ve developed a vocabulary. I feel articulate using that vocabulary, but I’m also getting bored with it. That work can become formulaic. I thought the exhibition and book came at a very good time. I’m fortunate it happened at this stage of my career as an artist. One can begin investigating new avenues and new ways of doing things.

Guernica: There are a lot of symbols or icons, clothing or costumes, in your portraits.

Pieter Hugo: Often that is just privy to make a photograph interesting.

From the series Boy Scouts

Guernica: The portraits of the Liberian boy scouts are quite interesting. Can you talk about these images?

Pieter Hugo: That’s a good example. That was really serendipitous because I was on assignment in Liberia to photograph Ellen Johnson Sirleaf—the first female African president—for an American magazine. I finished the shoot and decided to stay on in Liberia for a while, so I was having a beer on my hotel porch and these boy scouts walked past. It so happened that one of the boys was the son of the fixer I was working with. He explained to me that most of the boys were ex-combatants during the civil war.

I guess if one is aware of what your preoccupations are, if you keep your eyes open, they’ll show themselves. It also made me realize that you don’t need to go to the jungles of the Congo to make interesting photographs. It can be around you. You just have to open your eyes to it.

Guernica: You graduated high school in 1994, the year the first democratic elections took place in South Africa. Can you talk about how that influences your work?

Pieter Hugo: I grew up in a middle to upper-class house with fairly liberal sentiments, but to me it was always very obvious that the society I grew up in was not ideal and needed to change. Since I was a kid it was apparent it was going to change. It wasn’t sustainable the way it was going on.

My work is deeply tied to my experience growing up in South Africa. It’s very hard to separate that—as much as I’d like to think they are completely personal prerogatives, they are still tied up in the topography of the place I grew up in and the constant negotiation of that place. It’s a problematic place. One constantly questions where you fit into it, or don’t fit into it, or should you bother fitting into it. I guess photography, in the beginning, really gave me an excuse to go out and engage with that, which I think is what good photography is about. It comes down to an engagement with the world.

Guernica: How were photographers working before? What was the mission before, and is it different now?

Pieter Hugo: It’s completely different now. Not that long ago the idea of collecting photography in South Africa did not exist.

Guernica: So it was very functional?

Pieter Hugo: Very functional, although there have always been photographers doing work that wasn’t purely functional. There was a cultural boycott. One grew up never seeing fine art photography in museums. The work one saw in museums wasn’t international. If sports teams played in South Africa you were blacklisted around the world, international sports were boycotted during the period I grew up in. So it was really an isolated place, in a weird way. You were acutely aware that you were at the end of world and the rest of the world didn’t like you and didn’t approve of your political paradigm. So, I learned about photography through photojournalism.

Guernica: You can feel this in your work, but there is something distinctly different from your work and that of a news photographer. Why do you think that is?

Pieter Hugo: I don’t really operate within that call and beckon paradigm anymore and that really creates a different vocabulary. I do assignments, but the kinds I do are for The New York Times Magazine, where they really take time to let me explore something properly. It’s a very different type of journalism, like slow journalism, as opposed to the daily mull of a newspaper. It’s no disrespect, but it’s not particularly interesting to me, that world. I’m not suited to work in that world.

Guernica: I recently saw Beyonce’s “Run the World (Girls)” video. I can obviously see your photographs referenced, but I also see Ed Kashi‘s work and the visual language of a variety of photographers. Borrowing isn’t anything new, but to see the work taken for a glossy commercial purpose is a bit jarring. An homage? An appropriation?

Pieter Hugo: I honestly don’t give it that much thought. A part of me just thinks an original idea is like original sin. It happened a long time before you were born. I am indebted to so many people. I guess if you acknowledge it in some way or another, it’s OK.

From the series The Hyena and Other Men

Guernica: As long as you’re not Richard Prince.

Pieter Hugo: Exactly. The Beyoncé thing I kind of laughed about, but when I saw the hyena men in the Nick Cave video I was pissed off, actually, because I would have loved to do that video. I’ve always been a big fan of Nick Cave.

Guernica: Others may disagree, but in the Nollywood work, I see some comedy.

Pieter Hugo: A lot of people have missed that element of it. It was my Tarantino. I wish more people would see that. But you know what is happening, there’s a lot of reaction to that work. There were particularly strong reactions. One of the Nigerian authors who worked with me on Nollywood had threats made against him for collaborating with me on this work. He was called a race traitor. It’s quite scary when academics start dictating to artists that they should be politically correct or follow certain rules of behavior—which means we have to start making dishonest work, which means it becomes didactic and propaganda in nature. I find that very troublesome, very problematic. It’s taken me a long time to figure out why it affected me so deeply. It really upset me. It was never my intention in any way.

From the series Nollywood

Guernica: How is the reaction, if you were to show the image to a Nigerian as opposed to a European or American?

Pieter Hugo: It depends. When you want to look at the Nollywood work and read it as an itinerary of the Nigerian film industry, of course it’s inaccurate. But if you want to read it as, this is a creative person’s interpretation of the phenomena, and has drawn inspiration from the aesthetics of the phenomena, and the audience’s reading of the phenomena, then critique the work on its own merits. Say, “they’re boring photographs where everyone seems to be placed in the middle of the frame.” But of course I’m not an anthropologist. That’s not what my preoccupations are. I found those criticisms debilitating for a really long time. It took me a while to work through that.

My experience with the vitriolic criticism that has come from that work made me very conscious of how damaging it can be to engage your work on that level and to try to dictate to people what they should or should not do or how they should or should not approach the subject matter. And of course on another level it’s completely condescending, assuming custodianship of other people’s culture. There’s something incredibly patronizing in doing that. In Nigeria you are dealing with the third largest film industry in the world; the majority of the people read newspapers every day. In a way, the critic is more racist and more condescending. The racist word, using racism to critique anyone, unless it’s completely overtly so, is a very dangerous thing to do. It’s not something that should be taken lightly or thrown around without careful consideration.

From the series Messina/Musina

Guernica: Do you think it is your responsibility as a photographer to provide interpretation of what you see?

Pieter Hugo: As an artist it’s not my responsibility to provide a responsible rendition of how the rest of the world should perceive or not perceive Africa. Firstly, I’m not really concerned with Africa, I just happen to work here and it’s become an extension of my topography and the world that I inhabit. Continually ghettoizing it in that way is also very dangerous, or thinking of things as purely Africa, all you are doing is perpetuating this notion of otherness in some way.

Guernica: How is the approach of a photographer from Europe or America different? How do you see someone like Tim Hetherington‘s work?

Pieter Hugo: In many ways I think Tim Hetherington was a much more dedicated photographer than I am to his themes. He lived in Liberia for years. I definitely wouldn’t have stuck it out there for that long. Tim had an interesting hybrid of preoccupations and influences that comes through in his work. He was quite unique in his own way. He wasn’t scared of experimenting and definitely wasn’t scared of taking the time to do so.

Guernica: You knew him well?

Pieter Hugo: He was a friend of mine. The day I photographed the boy scouts I went to his house. Tim was so happy moving to New York. He found it incredibly liberating. I think he was just one of those people who was an outsider, even in England. He found it frustrating that he went to very posh private schools, but his family had made money just recently. He always found himself to never quite fit in. That’s why he found America so liberating. You can move somewhere and reinvent yourself. We had a good dialogue around that issue: the experience of being an outsider. This is part of the process, of why I often need to go away to make work. It’s not so much that the theme is exotic. Rather, it awards me the isolation of not being distracted, and allows me to get on with what I really want to look at.