By Peter Richardson

The May 7 issue of The New York Review of Books contains a letter to the editor that could have come from me. It responds to Dan Chiasson’s piece, “Prodigal Bob Dylan,” which the magazine ran in February. Chiasson, a poet and critic who teaches at Wellesley, wrote the following:

Having written extensively (and recently) about the Grateful Dead, I was struck by the casual dismissal of Jerry Garcia. Even more striking, perhaps, is Chiasson’s mode of dismissal, which is ingenious. In one stroke, he not only attributes Dylan’s shortcomings to his collaborators, but he also makes Dylan’s stumble resemble a virtue: namely, generosity. If only Dylan had correctly assessed Garcia’s talent deficit, perhaps the 1980s would have been another monument to Dylan’s greatness.

Garcia wasn’t only a musician and friend, he was more like a big brother who taught and showed me more than he’ll ever know.

It’s true that Dylan thought very highly of Garcia; that much is clear from his 1995 eulogy:

Eulogies bend toward charity, and Chiasson might plausibly maintain that, once again, Dylan’s excessive generosity was on display. But I wonder whether Chiasson would challenge Dylan’s assessment of Garcia’s ear, dexterity, range, or signature guitar work—and if so, on what grounds?

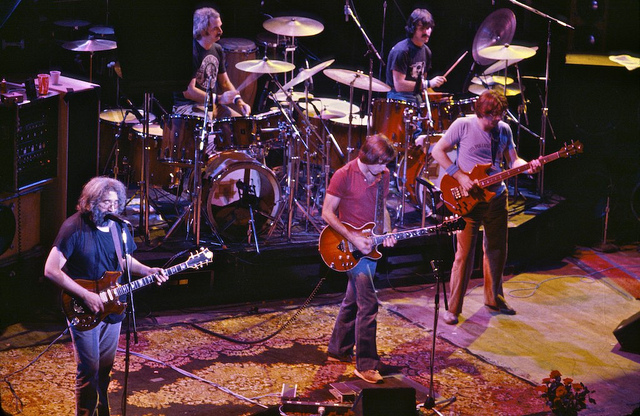

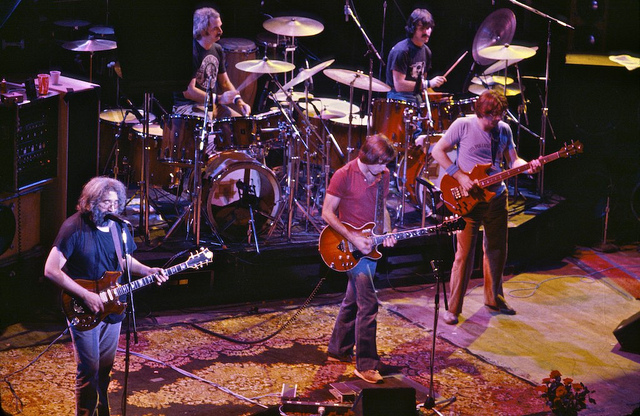

It’s also true that when they toured together, the Grateful Dead were thriving and Dylan was foundering. Although the Dead admired him, he needed them rather than vice versa. One of Dylan’s biographers, Princeton historian Sean Wilentz, remarked that “these years marked a prolonged, depressing setback.” The Dead found Dylan notoriously difficult to accompany, and he later admitted that they understood his songs better than he did at the time. The resulting album was largely a Dylan production, and Chiasson is correct that it was a stinker. Even so, that brief collaboration eventually led to the more successful Together Through Life (2009), which Dylan cowrote with Grateful Dead lyricist Robert Hunter. (Hunter and Garcia were inducted into the Songwriters Hall of Fame earlier this year.)

The published response to Chiasson came this week from New York Review of Books reader Rick Holmes. “I find it ridiculous,” Holmes wrote, “that [Chiasson] stigmatizes Jerry Garcia and Tom Petty as ‘minor talents.’ Dylan also collaborated with Roy Orbison and George Harrison in the 1980s. Perhaps Chiasson also considers them insignificant.” And so on in that vein. Chiasson replied as follows:

Let that second sentence sink in. Jerry Garcia was a radio act of that era? Also, ZZ Top and Wang Chung? Is Chiasson ignorant of Garcia’s work, or does he only assume that we are? Notice, too, the sarcastic reference to “great geniuses.” Why the snark if the judgment is well founded?

The sarcasm masks a significant move of the goalposts as well. The question was never whether Garcia and Petty were great geniuses, but whether or not they were minor talents. Chiasson’s answer is that they were minor compared to Dylan, presumably at his best. This sets an unusually high standard, but some of Dylan’s collaborators apparently rose to it. “Roy Orbison and George Harrison are indisputably major,” Chiasson continues, “but when was the last time you cranked a Traveling Wilburys tune? That was a lifeless, sleepwalking ensemble, and you know who I blame? Tom Petty.” This time, no fewer than three major talents were undone by a single inferior—snuffed out by a solo, perhaps.

It’s unfortunate Holmes gave Chiasson so much room to maneuver. If the focus had fallen on Garcia, Chiasson would have struggled to defend his verdict. By introducing Orbison and Harrison gratuitously, Holmes also permitted Chiasson to concede a symbolic point while sticking to his original judgment.

Though I wouldn’t dream of disputing taste, I detect in this exchange an intellectual sin that my dissertation director used to call “contempt prior to investigation.”

Although that judgment was embedded in the capillary action of a long article, the casual dismissal of Garcia is part of a longstanding pattern that I challenge in my cultural history of the Grateful Dead. And though I wouldn’t dream of disputing taste, I detect in this exchange an intellectual sin that my dissertation director used to call “contempt prior to investigation.” Chiasson’s tone, which seems to compensate for that critical defect, is very much of a piece with the original dismissal—clever but not wise.