The phone rings and you answer. The courthouse needs an ASL interpreter for night court, right now—it should take five minutes, are you available. You’ve never done this before but you have the time and you answer yes. You don’t know until you arrive that the defendant has been charged with murder.

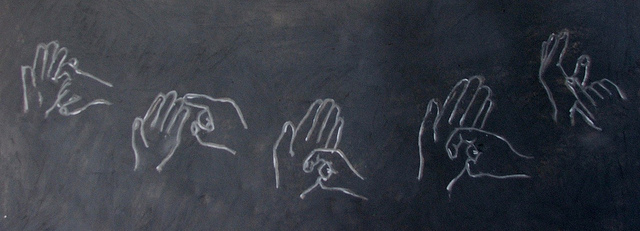

His attorney has only met him once before, and they wrote back and forth on paper. He has never used an ASL interpreter. You explain that from now on, he should always use an interpreter and not rely on writing in English. You ask questions about their communication so far, and did the defendant seem to understand him in writing? You are told that the defendant’s first language is actually Spanish; he can write in English, but it’s not very good.

This person has been charged with murder and your interpretation could be the difference between a verdict of guilty or not guilty.

You start to tell the attorney that deaf people vary in education and language skills, but then you are interpreting between the attorney and the deaf man charged with murder, who would be cuffed except he needs his arms and hands to sign to you. You don’t have time to judge, to be afraid or to be disgusted. You only have time to work, to be sure you understand and interpret, and do it well, because this person has been charged with murder and your interpretation could be the difference between a verdict of guilty or not guilty.

You go on to interpret meetings with more attorneys—the leathery New Yorker and the younger lady—for almost two years. You learn that there will be no burden of his proving to be not guilty because that is not on the table. He killed his girlfriend and that is undisputed. This is a relief to you as an interpreter because there is no ambiguous “referent to a crime that may or may not have happened” or “the evidence possibly implementing guilt with an alleged weapon.” These phrases would not translate to ASL well at all. You embrace the concrete language of the concrete crime, you interpret factually and you reflect the parties involved. You get comfortable voicing questions like, “When you first stabbed her, was she lying face down or face up?” and, amazingly, you do not emotionally absorb any details of the crime.

You interpret about cleaning up the blood. It is not your blood and not the blood of anyone you know and so you do your job, and in a fucked-up way you enjoy it because your work is not mundane and because you are good at it. They have chosen you because you are good at ASL, but what they have neither realized nor factored in is that you are also tremendously good at remaining neutral. You don’t hate the deaf defendant for stabbing his girlfriend to death; you don’t feel badly for him that he could be sentenced to life in prison. You are neutral because you lack empathy and sympathy in general, even for friends and family, because you grew up with a sick mother and had to put your foot down somewhere, because once the faucet of emotions was opened, there would be a never-ending waterfall of helpless depression and you were never going to be that person. That’s why you were a good teacher for the severely handicapped and that’s why you are a good interpreter for murderers.

When you’ve heard about the stabbing a thousand times over the next two years, it’s not so shocking to finally see the photo of the victim’s small body folded neatly inside the barrel he put her in. The DA showed an endless collection of photos of the crime scene: the apartment, the bedroom, close-up photos of blood and knife marks, autopsy photos, the actual bloody knife. But it was the barrel that was the surprise. Bright blue plastic, 22 inches in diameter, and nearly five feet tall—enough to accommodate a standing, hiding human being. Ironically, it was purchased to hide a dead person who had been carefully folded, like laundry. The body was small and the barrel was big, big enough to also hide all the crime’s evidence, the bloody sheets, blankets, pillows, and clothing, both his and hers. It was out of proportion in physical size and significance. Its presence added an absurd quality to the solemn courtroom. It brightly colored the otherwise empty spot you stared at as you tried to avoid eye contact with anyone.

You get through all the attorney-defendant meetings, psychological interviews, witness interviews, and realize on the day the evidence was unveiled that you’ve never seen a picture of the victim, his girlfriend. You have said and signed her name a thousand times. You know her Facebook usernames. You know how she was killed. But you have had no occasion to see a picture of her. You don’t know what she liked to do or whom she hoped she would grow up to be. It was easy to forget there had been a victim, a partner to the dance. Maybe this was necessary to keep you as the interpreter from feeling any sympathy for her lost life. In this way, it was actually easy to detach from the reality of the crime, since she wasn’t talked about like a person who had ever lived. You asked questions to come up with a defense to save his life; not hers, which was gone.

It also means that if the lawyer says “you’re getting twenty-five to life” and doesn’t add “I’m sorry” then you are not supposed to add “I’m sorry” even if you really are.

Of course his attorneys didn’t ask questions about her hobbies. What they needed to know about the victim was what she was doing on the day that he stabbed her to death. Those are the questions that you interpreted, so that’s what you know about. You could only satisfy your curiosity through the questions the attorneys chose to ask. You had no voice of your own to ask with. The case was a puzzle to which only the defendant had answers.

An interpreter is not supposed to side with either party they interpret for. You cannot favor the deaf signer, or the hearing and speaking person, in any emotional way. You cannot be disgusted by the message you are interpreting. If the deaf person signs FUCK YOU, then you have to say FUCK YOU, and you can’t omit it because you feel uncomfortable. It also means that if the lawyer says “you’re getting twenty-five to life” and doesn’t add “I’m sorry” then you are not supposed to add “I’m sorry” even if you really are because you have just spent two years together in something like a relationship.

You see the barrel like a big blue ethical divider that provides a contrasting point of view. The DA appeals to the jury’s sense of outrage and disgust that the girlfriend’s body was folded into a 22-inch diameter barrel, as if that took the killing to a whole other level. The barrel represents a barbaric crime planned in advance, indicating a murder charge, that there was a reason the defendant bought such a barrel. But your side, the defense, knew the barrel was an innocent victim in its own right—a victim of perception. The barrel was incidental. There was no grand plan.

The judge issues a verdict of murder in the second degree. Everyone watches the court interpreter sign the verdict of murder in the second degree. The defendant is made to rise, and just like that is whisked back to the holding cell and back to prison. No goodbye. The six-week trial ends on a Friday and everyone is overdue to start their weekend and brush off the ugly emotional dust from the volcanic blast of serious crime. You stand, gaping at the holding cell that is already empty. You bite your lip to keep from crying. His attorneys leave the courtroom, defeated. You wait silently together at the elevator. The defendant’s mother and her boyfriend hug you and the attorneys, crying. You go home, knowing this is the end of something you will never forget.

Spending a few windowless lockdown hours was oddly cathartic. You always left whistling; feeling cleansed, lighter, spacey but redeemed.

You wonder if it was creepy to interpret for a person who brutally killed someone. You imagined hating him and barely being able to keep your hands from shaking, insisting that someone else take over this job. But this did not happen, and you surprised yourself as well. Perhaps it was the lack of emotion on both sides. His attorneys rarely became upset or mad, even when they discovered he had been lying to them. The defendant was a clear signer, polite to his team, even personable. From an interpreting perspective, he was very easy to sign to and understand. All the way through, you thought to yourself, why don’t you feel more emotionally affected? But spending a few windowless lockdown hours was oddly cathartic. You always left whistling; feeling cleansed, lighter, spacey but redeemed, like you had watched a matinee movie in the theater and the gone outside to discover it was almost dusk. Where did the time go?

Utter neutrality. Who are you that this should be your crowning achievement?

I gave a voice to a murderer, and observed so many others being committed alongside: a jury not fully performing its civic duty, careless interpreters mistaking vocabulary and facts, and expert witnesses withholding evidence. What I feel the least neutral about is the scourge that deafness causes, even in its own community. Deafness does not by any means have to result in poor parenting, spotty education, lack of language, social or emotional immaturity, low executive function, shallow relationships, underemployment, or crime—but, for this person, all of these setbacks were directly the result of his being deaf as an infant, and raised in a family and country that did not know how to solve that deafness with sign language, parental counseling, and proper schooling. Everyone working in the field knows these unfortunate facts, but the banner message of the deaf community is a positive one: “deaf people can do everything but hear.” The truth about the potential downward spiral that stunts deaf children, who then grow into stunted, deaf adults who may never recover linguistically, educationally, socially, psychologically and economically is real—caused not by themselves but by the system in place around them, beginning with the medical profession. No one wants to say this publicly; even deaf people who can make this statement fear backlash. Hearing professionals, and friends of the community, do not go public without cushioning such comments with success stories, lest we be viewed as taking down a community of people that has fought hard for the respect of being able. The community is wide and varied, and things are complicated.

The defendant was sentenced, and I had the chance to say goodbye to him. He thanked me for doing a good job interpreting for him. I enjoy my freedom while he is behind bars, and I go on to interpret for other deaf people—mainly those who have not committed crimes.

Somewhere, another plastic blue barrel is being bought for another purpose.