W

hen I was a child, growing up in Chicago, Illinois, I believed that people were not allowed to live in Florida. This belief was not altogether irrational. I knew that people saved up money to vacation in Florida, and if you saved enough, over a lifetime, you might afford one bright utopian day to retire there. Florida was dessert, the reward—not the quotidian main meal of life. My parents took me on my first plane trip to Sanibel Island in the early 1970s when I was six; worried, I asked my mother if people spoke a different language there. I sort of understood her answer, that Florida was part of America, but still it did not occur to me that a person could choose to live there. If that were true, why did so many people remain in the miserable cold and snow, about which we all constantly complained?

My feelings resurfaced years later when I was awarded a teaching assistantship to attend graduate school in Gainesville, the raggedy, windless, tropically humid north Florida college town known as The Swamp, an hour’s drive from either coast, nobody’s tourist destination. The job paid less than $10,000 a year, but to me it felt like winning the lottery. I was living at the time in a Chicago basement apartment with bars on the windows, walking frigid city blocks each morning to the L for the thirty-minute train ride downtown to my dead-end job cutting and pasting classified ads for an insurance trade magazine housed in a dingy office on the twenty-third floor of an anonymous high-rise. The good news from Florida came on St. Patrick’s Day, which I remember because I was wearing green wool socks which were soaked and icy by the time I made it onto the train home. Frozen ankles and euphoria in a subway car stuffed with damp and grumpy strangers. I could not suppress my elation: my cold dead days were over. For weeks thereafter I awoke in a panic at 3 a.m., certain a mistake had been made, Florida would rescind its offer, or, worse, that I would fail as a grad student and be forced to forfeit my prize, my very life. In the deepest levels of my being, I knew I did not deserve to live in Florida. Perhaps this was my DNA speaking, passed down from my Eastern European Jewish immigrant grandparents: You must earn the right to live in this beautiful place, work as hard as you can and don’t complain too much, God forbid you should be sent back.

Even now, these feelings persist—though I’ve lived in the South for twenty-five years (seven in Florida, the rest in a coastal North Carolina resort town)—despite the traditional Southern outrages, the plethora of shopping centers and housing developments with “Plantation” in their names, the Confederate flags on truck bumpers, the tolerance for intolerance. I see these signs, but I also see alligators and flamingos and cypress knees and Spanish moss, dolphins and palm fronds and pine cones the size of pumpkins. Even the clouds are bigger down here, as if the sky is closer to earth. Whether or not you believe in Him, God abides in the everyday of Southern life, not tucked away in churches and synagogues, saved for special occasions.

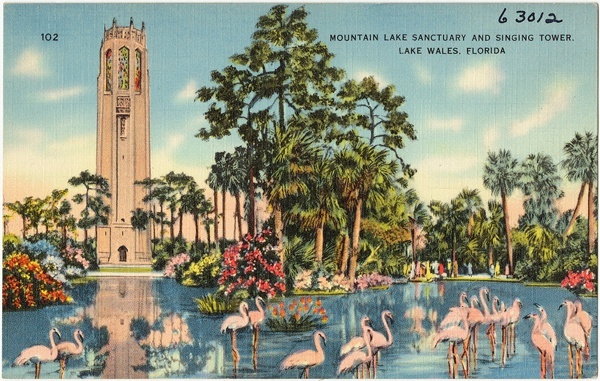

During my years as a Floridian, I began collecting vintage postcards I found in junk stores, the textured, trippily colored cards from the “linen” era, 1930 to 1950 or so, before cameras took over. I collected without any special intent—the cards were cheap and abundant, especially those that had been written on and mailed, making them less valuable to serious collectors. Most antique shops I visited had racks or shoeboxes stuffed with them, ten or twenty-five cents apiece, by the check-out counter, like an afterthought. Yet the cards were often breathtakingly lovely—like Florida itself, its throwaway beauty free for the taking, by the side of the highway speeding you to some less sensational man-made attraction. If you pull over on your way to Epcot, you might see a line of Egyptian-looking white ibises marching through grass so green it hurts your eyes. The colors on the old linen cards are oversaturated, improbable, hyper-real, yet so are the actual colors of Florida.

As a writer, of course, I also cherished the cards’ hand-written messages, words reaching through years, bursts of unintentional poetry:

Hunting season over, now we see places.

Sure is hot here & rains every time you look up.

Well I sure am at My self but am having a grand time.

We are living here in the courts of the Flamingo Hotel. Would you please send me some hangers (12) & an old bedspread—something that will go with green.

My favorite card of all says simply: We are surely enjoying our visit thru Florida, it looks like Paradise to us. The picture on this one—postmarked 1933—is of the famous Lake Wales Singing Tower, its image mirrored upside-down in its reflecting pool, as its architects intended, a full moon looming in palm fronds behind it. This is a common, even ubiquitous card—Singing Towers turn up in every lot of cards I buy on eBay—yet the Tower itself is extraordinary. Built in 1929, it still stands today, an ornate 205-foot neo-Gothic and Art Deco construction whose designers and craftsmen intended “to create perfect unity and symbolism,” according to its website. The tower’s grillwork includes “cranes, herons, eagles, seahorses, jellyfish, fin fish, pelicans, flamingos, geese, swans, foxes, storks, tortoises, hares, baboons, Adam and Eve, and the serpent.” Designs on the brass door depict the Book of Genesis, “starting with the creation of light and ending with Adam and Eve being ousted from the Garden of Eden.” The tower’s sixty bells still ring daily, as they have done since 1929. (Well, according to the printed description on my postcard, the carillon had seventy-one bells back then.) This is the Florida I love, the obsessive, teeming, Edenic South—the bells, the tower, the postcard, the junk shop, the website.