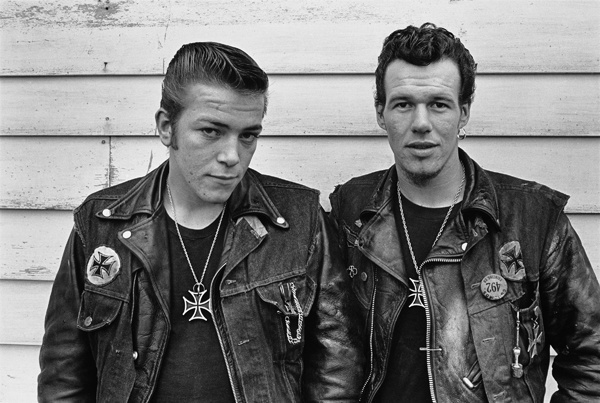

Copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery

The dust and the grease and the leather and the tattoos and the cigarettes; the dents in the otherwise gleaming chrome; the smudges of dirt; the gnawed bread; the jugs of cheap wine; the pool cues, the coffee cups, the bottles of Hamm’s and High Life; the mudspatter, the bitten fingernails, the windblown hair, the asphalt road.

The front porches and the picket fences and the children and the fields and the flags with their troubled allegiances. American, Confederate, white crosses. The wildflowers.

The aura of the deliberate projection of the self, the careful roll of the t-shirt sleeve, the backswept hair, the sideburns, the dyed, upswept hair (on the women), the hairspray, the pomade, the jeans, the lace-up boots, the emblem of the club, the belt, the Wayfarers and the cat eyes and the caps, the scarves, the embroidered patches, the vests, the lone earring, the blackened teeth, the chain. The coffin.

Copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery

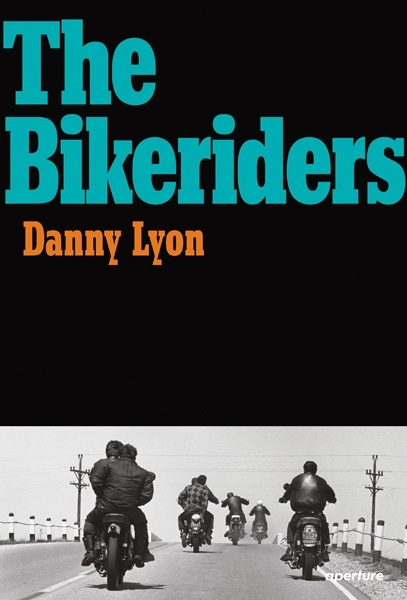

Rare was the person who was warned by Hunter S. Thompson that they were taking too great a risk, yet Danny Lyon, in his early twenties and just beginning his second major project, riding his Triumph alongside the motorcycle gang the Chicago Outlaws in the mid-sixties, managed to elicit some cautionary words from the Doctor. “I think you should get the hell out of that club unless it’s absolutely necessary for photo action,” wrote Thompson in a letter to the young photographer. But Lyon, fresh off several years photographing the front lines of civil rights protests in cities like Birmingham, Alabama—his images of police attacking demonstrators found a disturbingly familiar echo in some of last month’s pictures of the protests in Ferguson, Missouri, prompting discussion in the New York Times—was already establishing himself as someone who not only wasn’t about to leave, but was going to get in as deep as they’d let him. “Absolutely necessary for photo action?” His resulting book of black-and-white photographs and oral history interviews, The Bikeriders, republished in April 2014 by Aperture, is a resonate reply: Hell, yes, it was.

He worked from the inside out, not simply because he needed to truly see the bikerider, but because he needed to be the bikerider.

Both Thompson and Lyon were practitioners of what was then beginning to be called the “New Journalism,” or participatory journalism, or personal documentary; they didn’t presume to have a reportorial non-bias or hold their subjects at an anthropological distance, but instead threw themselves in the thick. For Thompson, who published Hell’s Angels: A Strange and Terrible Saga in 1966, this had damaging consequences: he suffered a vicious beating at the hands and boots of the Angels. Lyon encountered several ex-Angels in the Chicago Outlaws, but when Thompson’s letter arrived, he was already in too deep to extricate himself from their world, which by then had also become, in some ways, his own.

They ride against a backdrop of moody Midwestern skies in the shadow of Chicago, ditching their American cars (made just an afternoon’s ride away in Detroit) for Harleys (made ninety miles up the road in Milwaukee). “You just scream through there, all this groovy feeling…” they say, racing down the drag strip. With The Bikeriders, Danny Lyon set out, he writes, to “record and glorify the life of the American bikerider.” He worked from the inside out, not simply because he needed to truly see the bikerider, but because he needed to be the bikerider.

Copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery

Like James Agee and Walker Evans with Let Us Now Praise Famous Men a quarter century before him, and Mike Brodie with his rails-riding photographs in A Period of Juvenile Prosperity four decades after him, Lyon wanted to experience firsthand the romance of what he was depicting, at the races, out in open country, back home. His bikeriders are handsome and jagged, or hard-lived and maybe a little crazy-looking, with dangerous, fiery grins curling from their mouths. They wear a studied tough, they crush on their heroes, Marlon Brando, James Dean, on the cover of a magazine, scrapbooking their pictures like starstruck teenagers. They absorb them and transform themselves, becoming the founding fathers of a lawless fantasy, which is of course the American dream itself.

While Thompson’s Hell’s Angels may have presaged his subject matter, if Lyon has a real predecessor in form and in spirit, it’s Agee and Evans, whose seminal Let Us Now Praise Famous Men documents the lives of three Alabama sharecropper families. It was Agee, the writer, even more than Evans, the photographer, whom Lyon admired. (At one point in his career, he made a photographic pilgrimage to Agee’s hometown of Knoxville, Tennessee.) Remember that it was Agee who lived and slept among the families, while Evans took a room in town. Lyon was clearly as besotted by his subjects as Agee was his dirt-poor farmers; with his camera he captures them startlingly up close and intimate, and each frame is fully loaded with the materials of their world. Sometimes you are right inside, on the back of the bike; sometimes you’re peeking out an open window, but so close you can overhear the conversations as the riders gear up to head out on the road. And the conversations! They’re not reminiscent of Agee at all, really, but more of Studs Terkel: the text of The Bikeriders is composed of gritty and working-class oral histories, casual and seemingly offhand, rife with rhythm and repetition, straight from the horse’s mouth. You can hear the accents in their written speech. You get wrapped up in the strange stories they tell.

Though tinged with danger, and hinting at the racial prejudice that was prevalent in the scene, Lyon’s photographs are essentially romantic and glory-making.

Here, for instance, is Cal, one of the central figures in the book, and one of the few riders with whom Lyon kept in touch later: “You know, like I’d get salty. In other words, I told ’em how it is. And so this guy, man, they called him Jesus ’cause he looked just like Jesus Christ. The fucker had long hair, way down there, man. And it was combed straight and beautiful hair, man, you know, for a dude. Anyhow, he acted like God, too. That’s another thing. Every time we’d go on a run he’d find the highest place and he’d pray. You hip to it? The dude was a hypnotist, too, man. He used mass hypnosis. A whole group. Are you hip to this now? The dude was an artist and here he was a Hell’s Angel.”

Though tinged with danger, and hinting at the racial prejudice that was prevalent in the scene, Lyon’s photographs are essentially romantic and glory-making, the transcribed monologues and interviews revealing some of the unsettling sides of the Outlaws’ world, the things Hunter Thompson warned of. When Thompson got jumped by the Angels while writing his own book, it was in response to a remark he’d made, about the way he perceived some of them were treating their women: “Only a punk beats his wife,” he’d said. The Chicago Outlaws were no more noble. Here’s Kathy, one of most frequent speakers in the written section, and one of the main female subjects of the photographs, telling her and bikerider Benny’s how-we-met story. She’d agreed to meet a girlfriend at a bar, and showed up in a pair of white Levis, which, when she tried to leave, became a kind of canvas for the dark side of the Outlaws. “So I walks out the door real nice, bein’ grabbed about five times so that when I got outside, I could see on my slacks were just hand prints all over me.” In her interviews, she’s open about her marital troubles with Benny, who beats her black and blue, and like so many victims of abuse, she jumps from the offensive to the borderline defensive: “I’ve never seen ’em, really, take anybody that wasn’t willin’. I never have. Except in Dayton. But our guys didn’t do that.”

Copyright Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos. Courtesy of the artist and Edwynn Houk Gallery

Lyon doesn’t apologize, or examine; he simply lets Kathy speak. He also doesn’t comment in the book on the racism, though hints of it are evident in the pictures: the white crosses, the Confederate flags, the absence of any nonwhite person. This was a large leap from his previous project, working with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, photographing the civil rights movement in the American South of the early sixties. “Pictures have no mortality to them,” Lyon said to BOMB magazine in 2012. “The moment they’re made, they go into the future. I deal with that and I love it.”

Looking at The Bikeriders now is to do so with the knowledge of what was to come after: Easy Rider’s Dennis Hopper and Peter Fonda riding headlong into a prejudiced South; the real-life tragedy of the Hells Angels’ violence at Altamont, captured on film by the Maysles brothers and Charlotte Zwerin; and for the photographer himself. As Lyon told Photo District News earlier this year, “In my America, people were all different, they were handsome, and everything around them was beautiful. And most of all, they were free.” Revisiting these photographs, we come to understand them as the pivotal stage in what would become Danny Lyon’s life’s work; the beginning of a career whose main subject is outsiders and marginal figures—whether protesters (his recent Occupy movement series) or prisoners (his Conversations With the Dead on death row and the Texas prison system)—and whose primary political agenda is life, liberty, pursuit.

Rebecca Bengal is completing a collection of short stories and a novel. A former editor at DoubleTake magazine, her writing about photography has appeared in the New York Times, The Paris Review Daily, New York, Vogue.com, The Washington Post Magazine, and elsewhere.

To contact Guernica or Rebecca Bengal, please write here.