I have read before with fascination about the neurology of London cab drivers. Prospective London cabbies must memorize a preposterous amount of geographic information in order to pass the rigorous cab driver exam. Researchers have put drivers in brain scanners, wondering, is there something inherently different about their brains that allows them to memorize so much? Or does the memorization change their brains? They’ve found that in London cabbies’ brains, the area associated with memory is larger. This raises an enormous question, one that medicine still hasn’t figured out: when it comes to what happens inside our skulls, what makes an individual fall into or out of some standard called “normal?”

I thought about this on a Friday morning in early 2016, after my red-eye landed at Heathrow and I walked to find a cab. There was a particular museum just south of London that I desperately wanted to go to. For some months, I’d been visiting its website over and over. More recently, I’d been trying to convince my boyfriend that we needed to go to London for a weekend. He had some days off coming up and the means to go, I reasoned. It’d be romantic. “Plus,” I said, as if it were an afterthought, “I can go to that museum I’ve wanted to go to!”

The day we were to fly was also the day I was supposed to file a draft of my first book to my publisher. In the days leading up to the deadline, I hardly slept. I woke early and worked continuously, eventually closing my eyes past midnight but rising again in the dark, making another pot of coffee and continuing on. I paced the apartment. I read aloud to myself. I printed pages and wrote profanity in the margins. I muttered and cursed. I looked out the windows and wept. I handed in the draft just hours before we left for the airport.

I felt good! I felt great! The book was done! I told anyone who asked, and some who didn’t. Some weeks later, my editors would summon me and make clear, as gently as they could, that the work wasn’t finished, not at all. As they explained this to me in a small conference room over the course of an hour and a half, I tried not to cry. I managed to hold back tears until I was on the train home, and then kept at it for many days after. Eventually I’d tear the draft apart and rewrite the book entirely. Some months later, I’d do it again. The actual “the book is finished!” feeling wouldn’t arrive for another year and a half.

But when I flew to London, I knew none of this. I babbled about how I’d just finished writing my book, because I wanted to be done writing it. I’d had the contract for only about six months, but by that point I’d already been working on the project for six years. Since I signed the contract, everything that was hard about the project had begun to seem impossible. The subjects I was supposedly writing about intimidated me more than ever. The real people who figured into the story were variously uncooperative and upset. The book felt like a maze I had entered carelessly, and now I could not find my escape.

Outside Heathrow, we found a queue of black taxis, their drivers idling nearby. We approached one and got inside.

“Bedlam Hospital,” I said, pronouncing it that way, though in my head I knew it was spelled “Bethlem.”

The driver frowned and asked if I meant that Bedlam.

Yes, I said, I did: the psychiatric hospital. The campus was south of the city, I told him. There was a fine-arts museum there called the Bethlem Museum of the Mind.

The cabbie, to my surprise, didn’t know where the hospital was. He walked back to the group of drivers and, returning to the cab, we were finally on our way to Bedlam.

This book I was writing wasn’t a book I’d begun; I was its second author, handed it like a runner a baton.

What happened was this: In August 2009, I got a manila envelope in the mail from an uncle of mine. Uncle Bob lived in the California desert. I didn’t know him very well. We had seen each other at family reunions in Minnesota when I was a kid, and I had fond memories of singing silly songs with him while he played guitar. Sometimes, back then, he’d call our house and leave messages with new songs he’d recorded on his electric guitars and synthesizers, or monologues he’d performed as characters I found funny when I was in elementary school. Over the years, I had asked my mom—Bob’s little sister—what his deal was. She didn’t know much. The word she used for him was “crazy.” She remembered visiting him in hospitals. The word she used for those was “creepy.”

By the time I was an adult, Bob had sort of faded from my awareness. But I went and saw him once when I was in college, about two years before I got the envelope. I happened to be driving through his town, road-tripping with some friends, and we stopped for a bit. I’d never been to Bob’s house before. Inside, the air was thick with smoke. Bob was in his late fifties; he had long hair and a gut, and he wore glasses. He laughed a lot, and smoked constantly. He showed my friends and me his collection of guitars and amps. And he got very freaked out when one of my friends showed him his tattoo, yelling at me to promise I’d never get one. “The government tracks us with those things,” he said. Otherwise it was a pleasant visit.

Often these days people ask me, Why you? Why did he send you his manuscript? I can only guess. Maybe it was because I had bothered to stop by his house that time. Or perhaps he was looking for a writer to help him, and I was the writer he knew.

Inside the envelope addressed to me were sixty typewritten pages, stinking of cigarettes. The pages told Bob’s whole life story, typed in all caps. His prose featured lots of colons and few paragraph breaks. It was rife with misspellings and repulsive in several senses—especially when, a few pages in, a racist slur cut across the page. He’d included a cover page of sorts, the only page not typed in all caps, which summarized what was to come:

“IM ROBERT

this is a true story of a boy growing up in berkeley california durring the sixties and seventies who was unable to identify with reality and there for labeled as a psychotic paranoid schizophrenic for the rest of his life”

At first, I wanted nothing to do with it. I put the stack of smoky papers in a drawer and tried to ignore them. Bob called me and left messages that I also tried to ignore. But deep down, I was curious about what his story actually said. The drawer and I would stare at one another whenever I walked by. Eventually I gave in and opened it, and then opened the envelope and read the story. It was Bob’s story of himself—his childhood in Berkeley, and his first traumatic psychiatric incarceration at age sixteen. It detailed especially the decade that followed: his various attempts at finding a job, friends, a girl, his various attempts at regaining some semblance of normalcy. I found myself riveted by the manuscript, even though I didn’t fully understand it; by the time I reached his final line, I felt astonished, almost out of breath.

The next time Bob called, I answered. He wanted my help in getting his story “out there,” he said, because it was “true.” He told me he thought many people had never heard a story like his. On that point I agreed with him, but I didn’t think anyone would be interested in what he’d had to say about himself or anything else—it was, I felt clearly, the ramblings of somebody most everybody would rather ignore. And I didn’t have any idea how one would go about publishing a book. I tried to let him down as gently as I could.

But talking to him, and reading his words, had sparked something in me. I started writing about my memories of Bob when I was a kid, and this manuscript he’d sent me. I was in an MFA program at the time, and submitted it for workshop. My peers didn’t like this essay. They especially didn’t like portions where I’d quoted big blocks of Bob’s all-capitals, misspelled writing. They wondered if quoting his language verbatim was offensive or condescending. None of them seemed to have actually heard or understood the story Bob was telling.

I decided to stop submitting the project for workshop, but kept working on it. I’d sit at my kitchen table with Bob’s story beside my computer, study his passages carefully, and create my own rendition of each part of his tale. Over time, I settled on a style and a speaking position: I wrote in the third-person limited-omniscient perspective, tying “reality” to Bob’s description of it. It was a technique I hadn’t seen used much in nonfiction, but it felt like the only way to get other people to hear Bob’s story, to get beyond whatever assumptions they made from the way he typed and spelled and used punctuation, or that slur and his other racist, misogynist, ableist opinions. Or because of the phrase he’d typed across the cover page: “psychotic paranoid schizophrenic.”

Reading his lines over and over and over, I felt myself drawing closer to Bob’s story, as if it had a gravity of its own. I couldn’t explain what was happening to me, and I didn’t tell anyone about it. I see now that Bob’s story was transforming my entire head, but it would be years before I had language or context to explain how or why that mattered. I avoided speaking to Bob, for fear he might sniff out my interest in taking his project on. I didn’t want to get his hopes up. I told myself that typing in some Word doc was hardly the same as finding him a publisher.

Over time I came to think of my version of Bob’s story as a “cover,” which felt fitting, since he was a musician. Stylistically, a cover can stray pretty far from the original, but the original is still the point, the heart and soul. When Jimi Hendrix played the national anthem, he transformed it, yet it was clearly the same song.

By the time I finished school and moved to New York, I had written a full version of Bob’s story, though it didn’t really have an ending—or, I felt then, a point. I worked all the time and tried to make rent. I tried to abandon the project—and with it, what Bob’s story had begun to help me see. But occasionally, I found myself waking up early and just sitting with the story, feeling its power. Sometimes I’d fiddle with it, this stillborn artwork I thought no one would ever see. It felt like visiting someone in a long coma, or, perhaps, a corpse.

And then, one hot summer morning in 2014, my mom told me that Bob had died.

Shocked and feeling guilty I hadn’t done so sooner, I started telling relatives about this writing project I’d been working on, based on a story Bob had begun about himself. Initially, and to my surprise, these conversations seemed to go all right. But when I found an agent, who then sold the book, the news hit my extended family like an asteroid hits a planet. Various relatives were irate, suspicious of Bob’s motives as well as mine. They called me names and made threats I will not repeat. None of them had actually read my manuscript, or Bob’s. I think they were afraid of what my book might be, given what they knew about Bob and how they felt about the word “schizophrenic.”

I spent endless hours talking to my family on the phone and in person, working to cool things down. I told everyone all I wanted—all I wanted—was for people to listen to the story Bob had written. I’m not sure I fully understood yet why this was so important; at the very least, I knew, it was what Bob had wanted—to be listened to, to be taken seriously. One by one, I persuaded my relatives to let me interview them. I wanted to get the whole truth, I said, and that included how they saw things, too. My book is written as two threads, in two fonts: My cover of his story appears in one, and in another I’ve shown how he was seen by everything around him—by his family, by psychiatry, by the world.

Meanwhile, my new editors said the book needed to have a subtitle, and that the word “schizophrenia” had to be in it. After some back and forth, we landed on the subtitle A True Story about Schizophrenia—“true story” quoting the phrase Bob had written on the cover of his manuscript. Still, a book “about schizophrenia”—it felt impossible that I could ever confidently write “about” that. By then, I had been reading about “schizophrenia” for five years. All I’d figured out was that people understand it in a variety of totally incompatible ways. Uncle Bob believed that shrinks were being duped by Big Pharma, who were together duping the public, at the expense of people like him. Professional psychiatry believed Bob had a disease called schizophrenia — one that hadn’t been biologically verified, sure, but one that they felt was best treated with medication. Generally speaking, I realized over time, the press and general public has only ever heard psychiatry’s side, and so they consider that the truth.

Initially, I’d expected that medical and history books would show that Bob was wrong—of course there was no conspiracy between the pharmaceutical and psychiatric fields to over-medicate and stigmatize patients like him. But I read and read and the opposite started happening. I felt myself siding with Bob. I wondered, what would happen if we were to really listen to Uncle Bob when he talked about himself and his life, the doctors and others who treated him, the drugs he was made to take for decades until his death? What actually helps those who are experiencing madness (whatever that is)? And what doesn’t help people like Bob?

I searched for anything to assure me that publishing this book in a way that seemed to endorse Bob’s views wasn’t some epic mistake. I played Daniel Johnston and watched the documentary about him. I played Jimi Hendrix, who’d been Uncle Bob’s idol, and read about his particular trip on this earth. I played David Bowie a lot. Then Bowie died, and I played Bowie around the clock. I listened a lot to “All the Madmen,” where he sang:

‘Cause I’d rather stay here

With all the madmen

Than perish with the sad men roaming free

It was around that time when I became obsessed with a new museum in England that featured artworks by former psychiatric patients. It was located inside one of the oldest, and perhaps most infamous, madhouses in the world.

Bethlem Royal Hospital bills itself as the oldest psychiatric hospital on Earth, though it’s had several sites and identities and names. It was founded in 1247, just beyond London’s city gate. At the time it wasn’t a “hospital.” It was first a priory, called the New Order of Our Lady of Bethlehem; its main activity was fundraising alms for the crusades. Sometime in the late 14th century, “Bedlam,” as it had come to be called, began to be associated with housing mad people. For a long time, Bedlam was a popular attraction. Londoners and tourists would wander the grounds to gawk and laugh at those who were confined. “Bedlam” became a synonym for all mad hospitals, as well as madness itself—and for negative things stereotypically associated with madness, like nonsense, noise, and pandemonium. William Shakespeare, who probably visited, used “Bedlam” as a synonym for insanity in plays like Henry V and King Lear.

At various points during the hospital’s history, patients were confined, chained. They were subjected to supposed treatments like being plunged into icy water or spun around in chairs. In the 19th century, “mad doctors” were re-branded as asylum superintendents and then, in the early 20th, as “psychiatrists.” Etymologically speaking, a psychiatrist is a soul-doctor. Around then, the hospital’s doors were closed, and no more could the public gawk at Bedlam’s occupants.

Today, the 350-bed Bethlem Royal Hospital is part of the National Health Service. Its campus sits further south of the city, in a quiet suburb called West Wickham. Our cab pulled up to a wide brick building with columns above its front door. The Museum of the Mind was on the second story, up a broad staircase.

To either side of the staircase were two figures, men carved in stone. They were startlingly, unsettlingly larger than real men, as if madness actually physically swells a body into something monstrous. The faces were utterly grotesque—one pulled comically upward, the other despairing. A plaque explained that the work was called Raving and Melancholy Madness and had been carved by a Dutchman in the 17th century. For many years, the sculptures had sat to either side of Bethlem’s gates, greeting those who entered or departed. I shuddered my way past them. How familiar it is, psychiatry’s conception of the mad.

I arrived on the second floor, and turning to enter the gallery, stood facing a single painting dead ahead, alone on a wall.

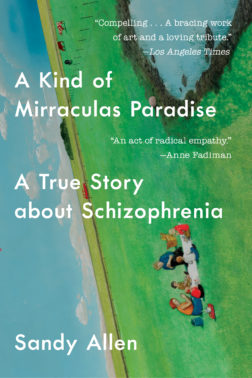

The painting was fairly large, three feet by four, done in a deft realist hand. Its colors were saturated, almost joyful. It depicted a great green field beneath a big blue sky. On a picnic blanket, a mother and father and three children sat beside a basket and a steaming pot on a little cookstove, their heads folded in prayer. Cows grazed nearby a pond. On a distant highway, a lone vehicle: a station wagon, a pop of red.

It was a pleasant scene; closer up, I saw there was a small skull in the left-hand corner. It was painted in 1971 by Canadian artist William Kurelek, a former psychiatric patient. It was called “Out of the Maze.”

I stood and looked at it and then really looked at it, and then had that feeling where a painting swallows you entirely, and for a while you are the painting—and then I realized I was sobbing.

William Kurelek was born to Ukrainian immigrants on the plains of Alberta in 1927. His father, a wheat farmer, was punishing, as was the world. Kurelek was shy and bullied. He eventually found painting, and thus his calling. He went to university in Toronto, but found the degree didn’t help him get jobs. He tried art school, but then left. As he described in his eventual autobiography Someone With Me, he commenced a journey “in search of myself as an artist.” He traveled to Mexico, where he was inspired by Diego Rivera. After saving up money working as a lumberjack, Kurelek crossed the Atlantic by ship. He arrived in London in 1952.

In London, Kurelek went to a psychiatric hospital called Maudsley. He wanted to be admitted. His goal, he later wrote, was to live there for free and paint. By his own account, he staged self-harm to trick the hospital staff. “Just as the protest marchers of today despair of attracting attention by peaceful means, and sometimes set themselves alright with gasoline or do physical damage to property, I decided violence against myself was the only recourse I now had,” he wrote. “Planning it all carefully beforehand, the day before an interview I exposed my arm and made a series of cuts from the wrist up, with a razor blade. Then I bound the arm with bandages reverently to soak up what blood there was.” According to Kurelek, the hospital subsequently “invited” him for an in-patient stay. “I was given a private room, which also doubled as a studio,” he wrote. He immediately got to work painting. This was Kurelek’s own account of his admission to the psychiatric hospital, though if you read about him elsewhere, he is frequently described as having schizophrenia. In terms of who is right, this was the exact kind of question I’d become tangled in for the years I’d been trying to write the “truth” about Uncle Bob.

Kurelek began with a small painting of a lumberjack, and then a large oil of children playing on a prairie. “I was half-conscious of play-acting a role as patient,” he wrote. “I had to impress the hospital staff, I thought, as being a worthwhile specimen to keep on, so that I could have the security of a home.”

Next, Kurelek set to work on what is probably his most famous painting, the piece to which “Out of the Maze” is responding. In the Museum of the Mind, I walked just around the corner and stood gaping at it.

“The Maze” is a face punch of a painting: a gigantic skull shown in cross-section, divided into little compartments, inside of which are exactingly detailed gruesome tableaus—a dead mouse, a group of crows pecking at a lizard’s corpse, a man being kicked by another into the snow, a sorrowful child alone on a plain, black-clad doctors leering at a naked frame. Kurelek later wrote that the painting depicted “all my psychic problems tied together in a neat package.”

In his book, he described each chamber’s symbols and their meanings—some to do with political strife, some to do with social isolation. “I was cut off from normal society on the sunlit road of life,” Kurelek wrote. “I plod heavily along behind the hedge trying to keep up with the others—dirty, uncomfortable, looking for snatches of sunshine now and then to break through the wall separating us.”

In the painting, the bone of the skull is porous, decomposing in the light of sun cast on a wheat field—wheat, because many of Kurelek’s troubles began with his father, and wheat was his old man’s menace. While Kurelek was at Maudsley, he wrote, the patients were taken on a field trip to Bethlem hospital, where Kurelek was able to snatch a few wheat specimens from an adjacent field to use as references for this part of the painting.

I wondered what Kurelek would make of “The Maze” and “Out of the Maze” hanging so close to each other now, jewels of this quietly revolutionary museum.

Vibrating with emotion, I continued walking through the gallery. Many more paintings and drawings captivated me, defeated me. Psychedelic drawings of cats by Louis Wain. A piece called the “Coming or Going Man,” by Kim Noble, showing, on one side of a wide white canvas, a back view of a man wearing jeans and sneakers, holding a guitar. He reminded me of Uncle Bob.

Some of the works were by famous painters, but many were not: drawings and sketches and watercolors contributed by the centuries of psychiatric patients here and elsewhere, people who have yearned to express themselves despite being locked up. The Museum of the Mind acquired Maudsley’s collection of paintings, including the Kureleks, when amassing its permanent collection.

The perimeter of the great gallery was hung thickly with paintings, and mixed in were historical artifacts—shackles, straitjackets, electroshock machines, instruments for performing lobotomies, contraptions for drowning and prodding and otherwise torturing the bodies and brains of those deemed insane. There were interactive exhibits, too. In one, viewers were asked to watch a video of an intake interview with a patient and decide whether or not she should be involuntarily hospitalized.

Given that Bethlem is still an operational psychiatric facility, not far from where I stood being asked to consider this seemingly hypothetical question, actual people were being held—some, inevitably, against their wills. Though water and spinning “treatments” are no longer in use, some patients are still given diagnoses and treatments they object to, ones some activists believe amount to torture. So I wondered how genuine a conversation this really was. Still, I was relieved to be in a place interested in even asking these questions. I felt the aching joy of having found something like company.

At one point, the gallery narrowed and I wandered into a tight space. The walls became puffy and white. Padded walls. Real ones, antique. I began imagining the real shoulders that had slammed into them, and half-hearing long ago screams. I walked faster.

In the gallery’s center was a square area lined with pastoral drawings. A sign explained that this space was for quiet reflection and contemplation—a space to take a moment, if you needed one. It was an accommodating gesture, acknowledging that to some, and perhaps to many, these objects and imagery might be difficult to confront.

The whole museum felt so different than any other fine arts museum or galleries I’ve been to, whose walls seemed, comparatively, preposterously long and sterile and white. In learning more about the gallery’s origins, I came to believe that this was perhaps because it was made in concert with mad people.

Organized psychiatric patient activism has been around since at least the 1970s, when the “mad pride” movement, as it’s sometimes called, really kicked off. The movement seeks equality, liberation, and justice for people diagnosed as “mentally ill.” But unlike many other intersecting movements for social justice and equality—black power, feminism, LGTQ+ equality—the broader world is much less aware of this movement. My sense is that the general public still does not realize there are people today who identify, proudly, as “mad.”

Not all psychiatric patient activists embrace a word like “mad.” Some call themselves “psychiatric survivors” or just “survivors.” Some call themselves things like “recovery advocate” or “peer advocate.” I’m not sure Bob knew the movement existed. I know he didn’t like the words with which he was “labeled,” as he wrote it, “psychotic paranoid schizophrenic.” The word he used for himself was “NUTS.”

(Myself, I’ve come to prefer saying “madness” to “mental illness.” The latter too-confidently asserts a metaphor of pathology I’m still unconvinced the evidence supports, one that is certainly damaging. And as a trans person who has read a lot of history, I’m generally skeptical of terms and concepts given to us by psychiatry.)

The Mad Pride movement has long been active in the UK. In the nineties, activists loudly opposed proposed new commitment laws that they felt would further impinge on psychiatric patient civil rights. Partway through the decade, the administration of Bethlem Royal Hospital announced they’d be throwing the institution a 750th birthday party in 1997. To activists, the museum was an ultimate symbol of the errors and malice of the psychiatric establishment, the most infamous madhouse of all time. Activists launched a campaign called “Reclaim Bedlam.”

At one sit-in, about 200 activists gathered outside one of the museum’s historic sites, many wearing white, stealing this color of innocence from the wholly not innocent doctors. They paraded about a giant syringe. The protest got a little media attention. Subsequently, during a series of conversations between activists and the hospital’s leadership, the hospital landed on the idea of the Museum of the Mind. The hospital had, for many decades, possessed and sometimes showcased patient art. A museum would be more formal, and could include an expanded collection of art centering the voices of those traditionally least heard: those who’ve been in the psychiatric system.

I had long supposed Uncle Bob’s firsthand account of being diagnosed with schizophrenia was something of a rarity. But at the Museum of the Mind, I continued to understand that Bob was not alone, not at all. So many who have been confined and wronged by psychiatry have written or otherwise expressed their truths. Yet their perspectives remain largely hidden. There is especially little room in the psychiatric discourse for the patient, like Bob, who vehemently dissents.

And since I went to Bedlam, I’ve learned about other galleries and museums that similarly present us with artworks created by people who have psychiatric and other disabilities—including the Living Museum at Creedmoor, in New York City, and Creative Growth in Oakland, CA. This in some senses overlaps with what’s called “outsider art,” wherein curators and others become captivated—for better or for worse—by the perspectives of those traditionally least heeded by our society.

After my trip to Bedlam, I searched for more firsthand perspectives of those who, like Bob, had been in the psychiatric system. I also spent more time learning and reporting about “the movement,” as it’s often called, broadly constituted. I hung out with and interviewed voice-hearers and shock survivors and out-and-proud mad people, folks who have been on the front lines of the fight for rights and dignity. I spent a long time listening to what they have to say about themselves and the system. We talked a lot about what they’d like to have instead of the status quo, and it’s often something they’re already creating. Worldwide, psychiatric patients are undertaking robust, if relatively modest, efforts to create mental health care “alternatives.” Such people have taught me immeasurably. A lot of what I’ve learned has to do with my own privilege and ignorance when it comes to thinking about madness and people deemed mad. During our conversations, one activist would often point out that I, like everybody else, had swallowed the “master narrative” and now had an opportunity to break out of it.

Sometimes these days, someone interviewing me about my book asks me to summarize the whole story, which means summarizing Bob’s life. What’s the takeaway? they seem to want to know. What’s the point? The point, I think, is that we, the supposedly sane, must practice the act of listening to somebody like Bob. We have been conditioned by our society to turn away from him. This, I believe, is our loss.

Madness can be terrifying, surely. But as my Uncle Bob knew well, even more terrifying is the way our society regards those who have gone mad. Psychiatric survivors tend to understand this point well: both nothing and everything separates us from freedom on the one hand, and on the other, that locked cell, that stigmatizing label, that damaging chemical. Not to mention greatly reduced civil rights and a permanently diminished status in the eyes of the law and society.

As is often the case with binaries, the idea that sanity and insanity are clear opposites is false. There is no stable “us” versus “them” here. The truth is, anybody can go mad. If you are taken to the emergency room in crisis, the staff there are seeing you on what’s maybe the worst day of your life. And to them, your behavior that day is all you are. They give you a diagnosis, and you become that diagnosis, with all that it requires—and all that it seems to mean about who you are.

William Kurelek painted “Out of the Maze” in 1971. That year, he returned to Maudsley hospital, where they screened a new documentary about him called The Maze (which has recently been re-released by filmmakers in Canada). Kurelek then presented “Out of the Maze” as a gift to Maudsley for their good treatment all those decades ago.

At first, Kurelek asked for some anonymity regarding his connection to the hospital; he wanted to spare his family embarrassment. Some years later, he changed his mind and allowed the museum to identify him. He explained this decision in his autobiography: “Sure, I have to honor my father and mother, but both they and I have to consider others, not just ourselves…In the end more honor will come to us for telling it as it was. For one thing the fact that I made a comeback to normalcy and success will blunt still further the social stigma on psychological illness. For another, those who themselves suffer mentally or emotionally—in the hospital or out—will take hope from the fact that someone else like themselves—a real living person with a real name—did eventually recover.”

Kurelek credited his recovery not to psychiatry or psychology, but to his later turn toward fervent Catholicism. God was the ‘Someone who walked with him’ referenced in the title of his autobiography. My Uncle Bob had likewise been a Christian, a man of faith. He also had two extraterrestrial encounters that were, to him, deeply spiritual experiences. Relatives of ours often mentioned, with concern, “the aliens.” Many of the people I’ve interviewed with psychiatric histories have found healing in spirituality. Many have had experiences others might dismiss as not being real. It’s an important question, whether we immediately deem such experiences to be evidence of some mysterious pathology.

William Kurelek spent the bulk of his life back in Canada, painting in a basement studio that was so small it was, essentially, a bunker. He finished some 2,000 paintings by the time of his death at age 50 in 1977. Along with his autobiography, he composed children’s books about life on the Canadian prairie. He lobbied unsuccessfully to have a nuclear fallout shelter built beneath his home, which matched his conviction that nuclear war was imminent. He believed this wasn’t an insane thing to fear. I don’t disagree.

And neither would Uncle Bob, I don’t think. He wrote about the global war he believed was impending. In his manuscript, Uncle Bob had also grappled with the potential consequences of writing so candidly about his hospitalizations and other experiences. He concluded by emphasizing that he considered his life to be some kind of tragedy. His life in the desert with his dogs and guitars—that he considered “PARADISE,” he made clear. He ended it: “THE WORLD IS NUTS AND RIGHT NOW THATS FINE WITH ME:”

My book, A Kind of Mirraculas Paradise: A True Story about Schizophrenia, was published in hardcover in January 2018. The summer after, my editors and I debated what the cover of the forthcoming paperback edition should look like. I did have one idea: William Kurelek’s “Out of the Maze.” I told them about the time I’d gone to a museum in London that features artworks by psychiatric patients. I explained about the painting, the first one I’d seen there, and how it had made me sob when I recognized something in it—something that made me feel less alone, as Bob’s sometime biographer or artistic accomplice or whatever I was. His patient zero. His first disciple.

Uncle Bob’s manuscript, those rank yellowed pages, had once been little more than trash in my mind. I’d held onto them guiltily, at first read them only reluctantly, and then they’d begun to grow around me, like tendrils. Now his writings are some of the most valuable objects I own. This knowledge made me feel intensely mortal, insufficient to ensure they’d live beyond me. When I was at Bedlam, I talked to a curator about my project, and asked him, with some trepidation: Would the museum take Bob’s manuscript after my death? When he said that they would, I felt something inside me release.

The paperback edition of my book came out in January. When I held a copy in my hands for the first time, I cried—as much from seeing this new version of my book and Kurelek’s artwork, as because my old name and pronouns had been replaced with my new ones. I knew, as well, that had Bob never sent me the story of his life, I might not have worked up the courage to be honest with the world about myself, about my difference.

On the cover of the paperback is Kurelek’s field and family and sky. Ingeniously, the designer tilted the whole image at an extreme sideways angle, a trick that forces you to blink and try to understand what you are seeing. A friend pointed out that the angle recalls Emily Dickinson’s: “Tell all the truth but tell it slant.” And that is what I hope to do, with this book: to make us all look twice at something we think we already know.