My father committed his when he was twenty eight, just three months after I was born. And a grisly one it was, too. The victim was some shook-looking fossil of a pensioner shuffling out of eleven o’clock mass in Carrigallen, which is where we called home until after the trial. It’s a tiny backward kip of a place, lashed to the side of a cliff just north of Glinsk on the tip of the Erris peninsula, where an icy wind slices through you no matter what kind of a day it is on the other side of the sign:

Failte Chuig an. . . / Abandon all hope ye who enter. . .

There’d be no need to go out of your way to bypass it even, because no road—main, bog, botharin or otherwise—will take you within an ass’s roar of the boundary, unless you really have a mind to get there. “The Grieving Corner,” my mother used to call it, and she’d be deadly serious, knowing full well the reasons why. She was by no means the only one either. You would want to be at least three towns over before you’d chance taking the piss out of the town and its murderous rumors, whispers that hung like mustard gas over every square inch of the place. Even then there’d be few enough takers. As it stands, there isn’t a guidebook in print that’ll make reference to it, I’ll put money on that right now, even from where I am.

But there was a time when it wasn’t the worst, I suppose.

We were well set up there to begin with anyhow. The three of us, snug as bugs in a little postcard cottage about a half mile down from Mannion’s butchers, which became Mannion’s hardware, which is now Mannion’s carpark—minus Mannion, who fell asleep drunk on the Galway road about ten years back. There was an old thatch roof on the house, but decent thatch like, the kind that will keep a bit of heat in the place if you don’t let it go to rack and ruin altogether.

Of course there’s holes in it the size of your boot these days. You wouldn’t sleep cattle underneath it.

Twenty-six stab wounds to the face and chest, she couldn’t have been much more than a mound of pulp and bone by the end. That and a flowery rain mac, I think.

Twenty-six stab wounds to the face and chest, she couldn’t have been much more than a mound of pulp and bone by the end. That and a flowery rain mac, I think. No pictures, though, so I can only speculate. I’m told it was quite a gruesome sight. All those insides turned out, the spray, the smell; to say nothing of the body and blood of Christ spewing out between shaky fingers. A whole chalk outline of soggy wafers from the stragglers who saw it firsthand. You wouldn’t be expecting it at that hour of the day, either, I suppose.

After that we moved up to Dublin, just around the corner from Glasnevin Cemetery. That leafy storage unit where all the old heroes and villains sleep side by side in single-seaters, awaiting genuflection. Where a drift of unbaptized babbies and choleric tenement dwellers skulk shoulder to shoulder in a crowded, mucky engine room. I’ve always been a fan of Dublin’s big bone orchard. The peaceful silence of it. Course we didn’t settle there just so that I could have my “what is the stars?” strolls around the plots. That was just a bonus. No: we were forced to go. Partly to be nearer to Mountjoy Prison, partly because everyone from the drunks on the street to the grand old mayor Johnny Joyce himself begged Mam to move before I grew old enough to become a threat. A threat, like!

The first one was a tragedy, the second meant a bad drop, but after the third—my father’s—people got spooked something awful.

As you would, I suppose, if I’m being fair.

By the time my father got round to measuring up, we were the most feared family in the county. Fuck it, the whole Island; why sell it short at this stage? Three in a row, each the same age his father, each the most gruesome event of that generation in the area—not that that took much doing. Then there was me. Sweet, innocent babbie that I was. Sure, I wouldn’t hurt a fly; I couldn’t walk yet, let alone hold a knife.

Ah, but there was that glint in my eye. How could you miss it, like. . .

“That young fella knows what he’s doin’ all right, sure I can see the aul’ glint.”

“I can’t see anythin’.”

“Ah c’mon, ye can of course.”

“. . . Can I?”

“Look closer will ye—sure ye’d know by him.”

“I see it now! Jesus, the divils’ in that child all right, no doubt about it!”

“It’ll be a better place when she gets the last of that shower outta here, poor creature.”

“Well now, any woman that’d marry into that quare stock can’t be the full shilling herself.”

“True enough.”

That kind of thing went on for a while. You’d be worn out ignoring it. They spoke up in raspy whispers when Mam passed, crossed themselves when they saw me rattling by in the pram, like Eastern European peasants in one of those old-timey horror films. Mam uprooted us quick enough once they started in with that carry-on. Never mind that she’d had a rake of friends in the village right up to the day he made her a pariah. Baking sweet rhubarb tarts, minding wild scuts of kids, organizing raffles; nothing the woman wouldn’t do for a neighbor out of pure niceness. For all the good it did her at the close. I suppose with me there they were afraid they’d catch something diabolical. Maybe they thought I’d jump up out of the cot and bite them or give them the gurgle of death or something. If I was given any kind of say in it, I’d have dressed the place up like a haunted house just to put the shits up them. Sound effects tapes turned up loud at all hours. Calling into pubs with red sauce down the front of my bib. Chewing on Disprin for the foaming mouth bit. The works. Except at that stage I was preoccupied with the shape of my fingers and the colourdy dinosaur mobile above the crib and trying to lift my head off the cushion for a decent look around, and you can only have so many balls in the air at once, you know.

In any case, we went without a whisper of goodbye or good luck, without a kiss or a blessing to my poor broken mother, only twenty-three years old but already so weighed down with the grief.

In any case, we went without a whisper of goodbye or good luck, without a kiss or a blessing to my poor broken mother, only twenty-three years old but already so weighed down with the grief. She was quite the vision once, I’m told, but it’s hard to see beauty in a face that never smiles. Made old long before her time and carried off long after the life had left her, you could say, if you wanted to force a bit of poetry over the thing (which sometimes I do). It was a hard road for a girl so young, but as they all said many’s a time: “Twas the life she chose.”

My father got the full skelp, obviously. You can’t go around knifing pensioners and expect a slap on the wrist. There’d be uproar. We had hoped they’d take into account the curse and realize that it wasn’t the poor man’s fault; he was simply afflicted with murderous genes, the way some are.

Shocker that that didn’t work, now that I think of it.

I don’t remember the trial of course, but I’m told there was a stink of hatred in the room that would undo your tie. I have a grainy Irish Times clipping at home somewhere of them all standing there on the day. This pack of bile-spittin’ onlookers with their well-rehearsed chants and flat caps pulled down low over their eyes, because they knew there was shame in what they were doing at the same time. The noise of them spilling over the gallery railing lent proceedings a sort of controlled anarchy, the type you might feel bubbling through a crowd impatient to get on with a lynching. The only one with a bit of class about them was the aul wan’s son, sitting there misty-eyed, clutching his mother’s cut up rosary beads, holding himself together as best he could. Outside the courthouse, bullhorns marshaled cereal-box placards into circles, figure eights and finally, an impressively mobile chorus line. Red permanent markers screamed MURDERER while passing muckers on Mossy Ferguson tractors voiced their agreement through bouts of honking, unintelligible Morse-code. It’s all there on Reeling in the Years, if you’ve seen that episode. Some even questioned the need to send the jury away at all, but procedure dictated that they at least do a quick lap of the building.

It was just good manners.

The judge called it “one of the most unspeakably vicious and brutal crimes in the history of the state,” which sounds a bit harsh to me. The young lad who killed that nun with the hacksaw in west Clare was surely worse, although they did say he was insane. That was the problem you see—Da wasn’t insane, not the gibbering, cuckoo’s nest sort of insane at any rate. The kind you could make hay with. The doctors, in fairness to them, did every schizo test under the sun, but nothing stuck. He wasn’t biting. Sitting there in the chair with a puss on him like it was his granny after getting aerated for no good reason. The shrinks (I love that word, “shrink”—when I was small I used imagine a load of scientists in a lab shrinking brains till you couldn’t fit any more bad thoughts in them) weren’t exactly falling over themselves to believe it either. True enough, his father—only allegedly, mind—and grandfather were convicted murders, but sure what was that save bad breeding? You’d get that anywhere, Malin to Mizen. Now a genetic predisposition towards homicide, let alone a family curse, that was something intelligent people found difficult to swallow.

Our Barrister, Vincent something or other, was one of these people. Scruffy, twitchy little fucker as I recall from an appeal hearing a few years back.

Our Barrister, Vincent something or other, was one of these people. Scruffy, twitchy little fucker as I recall from an appeal hearing a few years back. He pleaded with Da to keep his theories to himself, went down on his hands and knees saying they’d both be finished if he started in on that spiel. “They’ll hang you out to dry on that, Tom,” he says, “you’ll rot in the Joy for an age.” But we were insistent; bull-headed, he would have said. After all, how could a reasonable person not be convinced when they found out that each man committed his murder on the day of his father’s death? I mean, c’mon! After three generations this couldn’t be a coincidence. Something supernatural was involved and here was the indisputable proof. A rural Irish court, we were all certain, was about to set a world precedent by finding a confessed murderer not-guilty by reason of interference from an otherworldly force.

What a day for the history books.

Court report says he kissed me on the forehead as they led him out, but again I don’t remember. I’ve a few still images from the room in my mind’s eye, but I’d be fairly sure they were made up somewhere along the way. For one thing, yer man out of Judgement at Nuremberg is standing there arguing for the prosecution in one of them. That’d hardly be right. When I went back on my sightseeing tour years later—polaroid camera, tape recorder, no expense spared—nothing synced up.

Either way, we never touched after that; not even a handshake when I visited him at Mountjoy on my twenty-first. Though you’d have a job sneaking one in through the glass even if you wanted to, which, in case you’re wondering, I did not. I think he was afraid of getting too close for fear he might pass something evil on to me (Evil flu—stay in bed for life, do not operate heavy machinery, hide the fucking silverware). Not that that made any sense, but then again none of it made any sense, even to the few of us who believed it.

I was about twenty-three (twenty-four maybe?) when I decided that I’d had enough of being told things and it was high time I started rooting through the closets, digging out all the old skeletons. Of course, Mam gave me the bare bones in a low, faraway monotone, but the woman didn’t have the heart to delve any deeper, not with the little time she had left. On top of that I got to feeling like a bit of a shit coming in with the cup of tea and a big sly head on me. “Here you go, Mammy, two sugars and the drop of milk. C’mere, I was just wondering if they gave you back the knife da used to stab the aul one?” No, you couldn’t be at that, wasn’t fair. Even if one of these landed, it’d be cruel to distract her from her favourite daily pastime: staring glassy-eyed out the window for hours on end. Everyone needs a hobby, they say.

You’d have thought, all things considered, that I would have picked up a dose of this catatonia somewhere along the way, out of empathy or something, but you’d be wrong. Harsh as it might sound, I couldn’t scare up anything close to love for that washed out zombie plodding around in the Joy. It’d be an act, put on for someone else’s benefit, like the sorry-for-your-trouble strangers that don’t get seats at a funeral. I don’t even know the man. Not really. Our visits, far back as I can remember, have consisted of me fidgeting uncomfortably in my seat trying to block out the smell of piss and industrial disinfectant, among other things, and him rocking back and forth, avoiding eye contact and muttering away in tongues under his breath.

Magic moments.

Oh don’t get me wrong now, it was depressing all right—Christ, just looking at him would make you want to open your wrists—but I couldn’t shake the feeling that all that furrowed-brow bollocks on my part was a little bit forced. I felt for them both, in the way you do when you read about these things in the paper, and wished they could find a bit of peace in themselves, but you’d be amazed by how quickly you come to terms with this kind of stuff if you never actually experience it first-hand. Looking at Da was like gawking at a monument to the dead: it inspired curiosity more than anything else. And I was the curious type back then.

Anyway, despite my all my badgering, there was no convincing him to play the seanchaí on this particular topic. What he did do, which was decent of him, was direct me to an unpublished manuscript in the attic of our old family home. Apparently Mam’s brother, that irredeemable arsehole Gerry McLoughlin, had a morbid fascination with our family history to rival my own. Once upon a time he had interviewed pretty much everyone in Carrigallen who had any connection, tenuous or otherwise, to the murders. He’s a shite-talking taxi driver by trade, and will probably die behind the wheel of his rusted old motor, but considers his true calling another area entirely. Gerry was writing a novel you see, a “gargantuous tome of a novel,” maybe even the Great Irish Novel; but unfortunately, since Gerry has all the linguistic prowess of a tourettic vagrant, the book was unreadable. Throw in the collective unease that still festered, country-wide, around this murky business, and he had about as much chance finding a publisher as the lad with the Pedophilia for Beginners draft tucked under one arm. Anyway, a dozen or so rejection letters later and poor Gerry is left a sullen husk of a man with a drawer full of worthless pages and a hefty chip on his shoulder. Living, rent free I might add, in our old gaf.

Now I consider myself to be a reasonably patient person. You’d want to be with all the headbangers I’ve had to deal with.

Now I consider myself to be a reasonably patient person. You’d want to be with all the headbangers I’ve had to deal with. So when I tell you that after a bit of sleuthing, I broke into my uncle’s home (squatters’ rights at this stage, catching leaks in fucking buckets) under cover of darkness, stole the manuscript in question from his dresser drawer, and replaced it, Indiana Jones-style, with a carefully weighted forgery, all to avoid simply broaching the subject with him—a subject he will happily ramble on about for hours on end without any prompting whatsoever—well, you’ll understand just how head-wrecking the man really is. Ah get over it, you might say, let the fella tell his tall tales if it helps him fill the days.

Well fuck that for a game of cowboys.

If you play Russian Roulette with the taxis on Harcourt Street one of these weekends, you may well find yourself trapped in a child-locked Toyota Avensis at four in the morning, getting the full blow-by-blow account from Gerry himself. Then come back and give me the lecture and we’ll see where we are.

But back to more pressing concerns. According to Gerry, those who believe in the curse date its origins to a single ghoulish event in 1923, during the first fiery summer of the new Free State, the new world. The first time heavy sunshine fell on the raised tricolor. When little lost gunmen still roamed the fields, licking their wounds and plotting insurrection.

I’ll set the scene, right:

My great-great-grandfather, Manus McCarthy, along with his lovely wife and two year old son, Declan, owned and operated what is now, supposedly, a haunted pile of rubble. Back then it was known as The Abbey Springs and had the dubious honor of being the first hotel in the area, opened September 16, 1922. Closed, in a manner of speaking, on July 5, 1923; a bleak fuck of a day by all accounts. Business was bad from the champagne-popping onwards and really took a nosedive mid-winter as the building’s already-desolate reputation chased the last of the punters away. Think of the old industrial schools, places where even the furniture seems suicidal, and you’ll get a feel for Manus’ new venture. After a good few months of this carry on, shutting up shop was the only remaining option. The only remaining option for any ordinary man that is, but Manus, God love him, was of a different kind.

A slicker animal than they gave him credit for.

Or so he thought.

So he cooked up a scheme or he had a moment of inspiration. For the family’s sake I like to think it was the latter. I mean, murder is one thing, a rough brand to wear no question, but to have this kind of shambolic playacting run in the family. . . Anyway, as this hotel was heavily insured (how he got that rubber-stamped in the middle of a civil war is another story), burning it to the ground in the middle of the night was the only logical course of action, as you’ll find it is for many a tricky problem. Nothing to it really, not in those days. Can of petrol, few matches, quiet word with Walty Sullivan from a half mile down the road, and this incendiary solution works like a charm.

The local makeshift fire department (Castlebar; an hour and a half’s drive) arrived in a flurry of aimless movement, a bluster of cautionary commands: “Stay back. Stay BACK. Calm yourselves! We have everything under control here!” Chief O’Driscoll bellowed with savoured authority as he and his men supervised the atomization of Manus’s once-gleaming flight of fancy. So the fire raged long into the night, belching jet-black smoke into the hazy summer air while Manus, I’m sure, did his best to look believably distraught. With quenched embers still hissing in their ears, O’Driscoll and his crew circled the heap and found, much to their confusion, the contents of The Abbey Springs, from beds to cutlery and even a grand piano, stacked neatly in an adjacent field.

Now far be it from me to pass judgement. I’m sure this seemed like a good idea at the time, especially for someone in as financially precarious a position as Manus was; but I do wonder how neither the proprietor himself, nor any one of the five or six local young fellas who helped with the heavy lifting, saw this plan as anything less than a stroke of genius. You’d imagine that, regardless of the situation, the moment you find yourself standing ankle deep in mud, in the middle of a field, in the middle of the night, holding a piano, something has gone terribly awry.

Would you believe it though, this forehead-slapping act of fraud was not the worst thing to befall poor touched Manus that night? Oh God no, not by a long shot. Earlier that day, as he was plotting away to himself, Manus’ own father, entirely oblivious to what was coming down the tracks, had dropped stone dead and was lying quiet and cold on the kitchen floor, his only remaining function to be the first link in a very unusual chain that would stretch out across the generations.

A little later that day, Anne McDonagh, age 7 ¾, was running away from home for reasons which Gerry did not detail. She might have known, as we know, that hotels, especially unsuccessful hotels, contain hallways upon hallways of empty rooms in which a person could hide if they had a mind to.

It was in the corner of one of these rooms that her charred little body was found.

Here’s where things get a bit speculative.

Local myths are in short supply in Carigallen, for whatever reason. It might be that my own brood’s ghost story has, by now, roared down all others.

Local myths are in short supply in Carigallen, for whatever reason. It might be that my own brood’s ghost story has, by now, roared down all others. Or, then again, the banshees and faerie folk may have taken one look at the drab little shithole, with its lecherous trolls peering out from behind rows of pint glasses, its gossipy ghouls, all elbows and nostrils and pricked-up ears, and decided that the place was haunted enough. Who knows, really? But one bad penny of a scéal that has turned up time and time again over the course of the last hundred odd years, concerns a leathery old tinker woman who used stalk the bog on the far end of town.

Now in order to bring a bit of restraint to bear on this tale, something Gerry, whose account basically has her flying around the fields on a broom, unsurprisingly failed to accomplish; I am going to refrain from using the ‘W’ word as best I can, but you get the idea. Local lore tells of a shadowy, brain-addled creature, grandmother to every tinker in the area, whose screeching lamentations in the small hours would pierce the stillness of any moonlit night. Allegedly older than the town itself she was, and no tinker child took its first steps on Carigallen soil without a blessing from the woman. With a smearing of peat ash from the fire that burned day and night in her stone hut in the centre of the bog, these feral little newborns became part of a protected flock, precious and ever growing.

After the funeral, when the tears were shed and the whiskey drunk and the miniature coffin of Anne McDonagh surrendered to the earth, the old woman went to work. Tearing down her home with a strength they couldn’t explain and didn’t try—you wouldn’t want to be getting yourself caught up in that shit—she built up the fire and let it flicker and rage and climb to the heavens until the bog itself was ablaze. So she danced around the inferno, howling curses, venomous tongue twisters of things like, echoing back through the town where they were all lying there wide-eyed and shivery, and the noise was so high and shrill no one knew what was being invoked or if it was even words that were coming from her at all and just when they thought they could take no more, when their eardrums were all but shattered with the raw poison, the fury of the sound, that Howl, it stopped.

And when heavy silence had reasserted itself, when every still-pricked ear had emptied of all but the ringing, one name hung clear in the air:

McCarthy.

Make of that what you will.

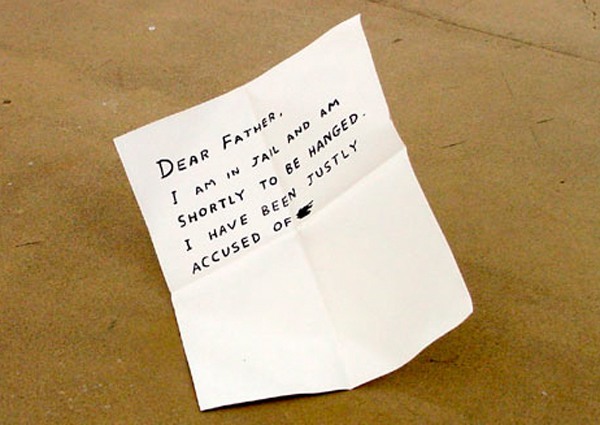

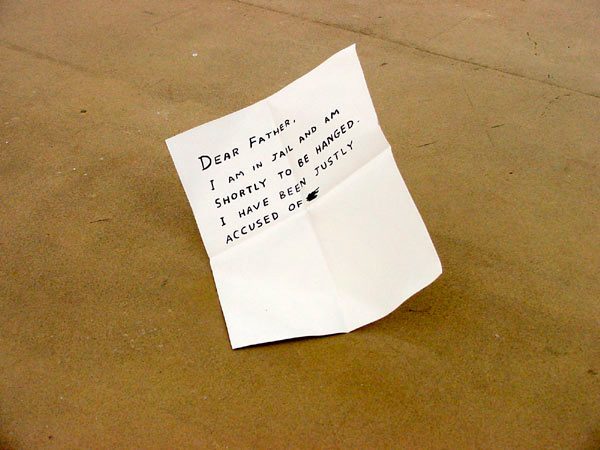

Manus, it seems, was a man who acted drastically when there was call for drastic action. In this case, it was his feeling that prison was not severe enough a punishment for such an atrocity, accidental and all as it might have been. Not by a long shot. No, he was crossing fingers and toes for death and was damn sure he was going to get it, too. Though he couldn’t just whip off the shoelaces and do it himself, much and all as he’d like to; Catholicism is a hoor that way. It had to be by another hand. So he came straight out with it, no messing about. Put the request in writing and all, had it witnessed and entered as an official plea. Said the judge’d be doing him a kindness.

Course Manus being Manus, it wouldn’t be as simple as all that. You don’t often get insurance scammers coming in looking for the last cigarette. Usually it’s all contrition this, and ‘think-of-me-children’ that, so the Judge didn’t know what to do with this dead-eyed specimen. The tinkers wanted him dead, or released without charge so they could do him themselves, but the judge hated the tinkers, refered to them in his journals as “an infestation of biblical proportions.” At the same time, giving in to the requests of child murders was not his style either. So by way of a compromise, he threw down life, roared and gaveled the rest of them out of his courthouse, and closed the book.

And that’s how it went. Manus lived the next twenty-seven years under water; slowly drowning, lost in a murky ocean of woe from which he would never emerge.

Cough-talk of curses and black marks and death days and woe betide the poor slip of a thing that ends up with Deccie McCarthy.

Declan, who watched from the crook of his mammy’s arm while they hauled his father away, grew up skittish, troubled. Made paranoid by the Chinese whispers he heard from behind bike sheds, corner pews, pub snugs. Cough-talk of curses and black marks and death days and woe betide the poor slip of a thing that ends up with Deccie McCarthy. Ghost stories, pooka tales to pass the time was all they were then. The thing was, though, Declan took all this hot air as gospel. The tinkers threw the evil eye on him any chance they got, and he came to believe there was nothing they couldn’t do to him, or indeed to any child he might bring into the world. Age 10, he swore off procreation. No kids, no curse, no problem. Said he’d go to the ends of the earth to make sure he was the last in the line. Boasted he’d take himself out of the picture as soon as Manus clocked off.

Then, in the spring of 1947, things fell apart. Wrecked drunk on stout and Powers whiskey at a dance in Bellmullet, himself and a girl called Niamh Egan retired to a nearby field, or barn, or cottage, or wherever was local and unsupervised, I suppose. Somewhere empty enough that you needn’t worry about leaving room for the Holy Spirit.

Flash-forward a few of months and the same day the prison doc told Manus “It’s cancer, I’m afraid; you’ll be lucky to get to the end of the year,” word trickled through that a mousey slip of a girl and her bull-elephant father were on their way to Carigallen to dig out whatever scurrilous pup was responsible for her sudden increase in bulk.

There’s no record of where Declan legged it off to—not that there was anyone really searching. Gerry had his theories though, one in particular that had been doing the rounds for a couple of decades. Said he got hand-on-heart intel from a local priest, an aul lad, who spent his twenties working the missions out in Northern Australia; saving Aboriginal souls, assuming they had them, that is. Seems they published a mug shot of some nameless Irishman in the local paper after an Abbo toddler turned up dead in the bush outside Queensland. Mangled dead. “On a stack of bibles,” he swore, “it was the same lad I sat next to in school; if it wasn’t for that wild bush of a beard I’d be certain of it.”

Course that could have been any Irishman. I mean, what was on that arid rock back then besides Irishmen, and half of them criminals, or apples from criminal trees? But the town knew better.

Granny Niamh refused to head back to Bellmullet with her father, said she’d rather wait around to see if Declan had a change of heart. By the time the baby was born, Declan’s mother had the girl settled into our family home, more out of pure shame, I’d imagine, than any feelings of kinship. A bastard child is bad enough, but a homeless bastard child, wandering around tinker bogs with that colour of blood in his veins. Sure, what chance would the little gasur have?

In the fifties and sixties, when everything went back to normal—worse than normal, boring—Manus and Declan became a bit of an urban legend, a tale they all had a different way of telling. One of those baggy boogeymen stories that’d put a bit of lightning into a child’s grey day. I’m sure Da heard it here and there. If things had turned out a little differently, I’d have probably heard it from the kids at school at some stage, kept quiet like I was listening to it for the first time. Maybe passed it down to my own kids knowing the last of it was long gone.

I suppose I could have had a couple of kids by now. If things had turned out differently.

God help any stray gobshite stumbling back from a lock-in at The Brian Boru; he’ll sober up quick enough if he runs into the pair of us on the anniversary.

He’s coming out now though. Just one more day and Dark Tom McCarthy is a free man. Oh they kept him as long as they could, even stitched him up on the odd assault charge while he was in there (the notion of that man throwing punches always makes me laugh). But sometimes your stint is just up, and there’s nothing anybody can do about it. Still, it’ll be good to see him in the sunlight. He could use a small bit of brightness at this stage in the game. Probably knows himself it’s the only way to end it; I might even get a smile out of him before it happens, though there’s a good chance he’s forgotten the mechanics of the expression by now.

I have it all planned out, meticulous as you’ll get, so there’ll be no hiccups. Early Sunday morning, streets should be clear enough. God help any stray gobshite stumbling back from a lock-in at The Brian Boru; he’ll sober up quick enough if he runs into the pair of us on the anniversary.

Lonergan, the top screw in Montjoy, talked me through the release procedure. After they give him back his bits and pieces he’ll get a couple of forms stamped and scurry his way past all the old faces: Mick Walsh with the lazy eye; that vicious fuck Ahern; and the big somber-looking young lad who works the door in the Jackson Court Hotel on Saturday nights. Then they’ll open that heavy blue door in the heavier blue wall and nod us out like we were both only visiting some hopeless psycho in B Block.

We’ll walk sharp through Phibsboro, tucked tight into the wall. Once we pass through the cemetery gates, I’ll slow it down a bit, ease the pair of us into it. There won’t be a soul above ground at that hour.

It’s a very peaceful place.

Dan Sheehan is an Irish fiction writer, journalist, and human rights advocate. He received his MFA in creative writing from University College Dublin. His writing has appeared or is forthcoming in numerous international publications, including The Irish Times, Notes From The Underground, Icarus, and Words Without Borders. His short fiction has been anthologized in New Tricks With Matches and in Doire Press’s International Fiction Anthology. He recently completed his debut novel and short story collection, and lives in New York City. Find him @danpjsheehan.