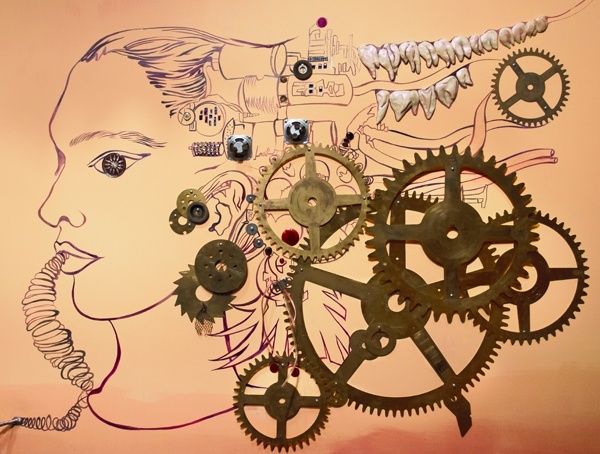

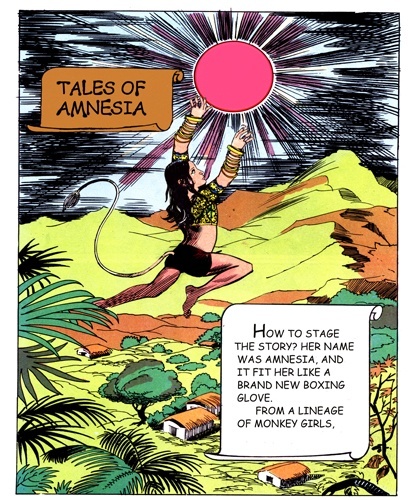

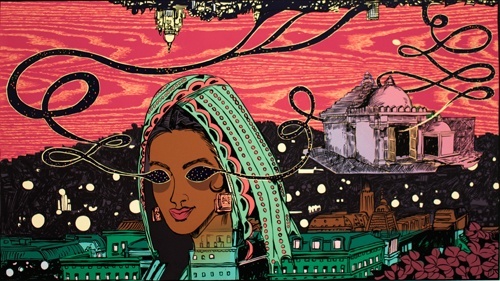

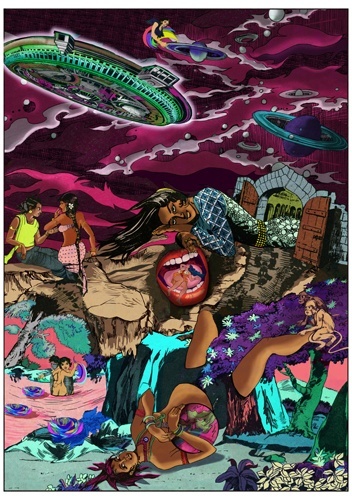

Chitra Ganesh, an Indian, Brooklyn-born artist, is not religious, but her work brims with visual and narrative references to Hinduism, Buddhism, and Greek mythology, the literary and art historical canons, folk tales, and pop culture. She recognizes both the emotional clout and cultural heritage of these symbols, and her paintings, murals, photography, and drawings offer a space in which to find the untold or forgotten story, guided by familiar clues. Her most recognizable works are her digital collages, comic strips directly inspired by the children’s books of Amar Chitra Katha, an imprint founded in the 1960s to teach Indian history and lore. Her focus on female power is erotic, dramatic, and primal—characteristics often attributed to the ancient narratives from which she draws and that are so often sanitized for modern life—and her attention to marginal figures, unresolved endings, and mass imagery reveals a reverence for the individual and subjective experience.

Ganesh, who completed an MFA in art at Columbia, has exhibited worldwide, and continues to reside in Brooklyn. Her new show at the Brooklyn Museum, Eyes of Time, is on the fourth floor in the Elizabeth A. Sackler Center for Feminist Art, whose centerpiece is Judy Chicago’s “The Dinner Party” (1974-9), an ode to 1,038 women in feminist history. Exhibitions at the Center’s Herstory Gallery revolve around one or more of the dinner party guests. For her new work, Ganesh chose to address Kali, the Hindu goddess; she was also invited to select art from the museum’s vast archive to showcase alongside her own. Pieces from Louise Bourgeois, Shoichi Ida, Barbara Jones-Hogu, Kiki Smith, as well as a circa-1760 Indian painting of the goddess Matangi and an Egyptian figurine of the goddess Sekhmet dating to 664–332 BCE, are on display as part of her project. Also featured is “Tales of Amnesia” (2002), one of Ganesh’s original digital collage works.

I met Ganesh at the Brooklyn Museum as she was putting the finishing touches on her mural. She was clear, outspoken, and open.

—Alex Zafiris for Guernica

Guernica: Kali, the Hindu goddess, is the center of your new piece. What was behind this choice?

Chitra Ganesh: Kali is interesting right now because she’s the goddess of this time. According to Hinduism, we’re living in the Kali Yuga, which means the “dark ages.” She’s the goddess of now, in a way, and she’s also the goddess of time and change, and all of these other things—it’s complicated, because I’m interested in her, and I’m interested in representation that falls outside of what would be socially appropriate, or acceptable, or beautiful. The world is going through a very fundamentalist moment. You have right-wing politics and misogyny and religion employed together everywhere—here [in the US], with issues like abortion. Religion is a very fraught and complicated topic, but at the same time, like all grand historical narratives, there is a potential for challenging, or rethinking the kinds of subjectivities that these meta-narratives produce.

Guernica: You grew up in Brooklyn and Queens with Indian parents, and visited India a lot, which you continue to do. Was your community very religious?

Chitra Ganesh: No. I think that in the diaspora, and among immigrants, religion becomes a vehicle for the transmission of cultural information, and cultural codes, and this does end up re-inscribing certain things about the religion—like caste. Caste discrimination and hierarchy are still a very fundamental and violent part of Hinduism. My family was upper caste, and that was very clear. I feel like caste and religious practice are inextricable, actually. The kinds of access that you have based on caste, for example—people who are Dalit, or untouchable, are not allowed to enter temples. They are banned from a certain kind of worship, whereas people who are upper caste tend to be priests. So there is power there, but I also think that most of the people who immigrate outside of India are upper caste. By and large, I would say that the people who immigrate at least have caste privilege—if not financial or cultural privilege.

Guernica: These Indian comic books you read as a child, which influenced some of your later work—did they address caste?

Chitra Ganesh: Some of them do, but not in a critical way. B. R. Ambedkar was an Indian revolutionary, and helped write the Constitution. He converted to Buddhism and converted a lot of untouchables to Buddhism. He’s got a great comic, he’s part of the series. There are a number of Muslim stories, more Islam historically related religious stories. So, it’s a mix, but I would say that out of five hundred of those comics, a hundred of them get circulated more, and these are less critical.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco

Guernica: Did you feel a disparity between your life in the US and India?

Chitra Ganesh: More a discrepancy between my life within the home and my life outside the home—my life within public and private space. In terms of here and there, there were some differences, but New York and India were very different when I was growing up in the ’80s. Definitely in terms of the visual and popular culture I encountered within my home—[that was] very different from the complete lack of representation I saw of South Asian culture outside of that space. Or when I did see that representation, it would be at a class trip to the Met, where everything that hailed from South Asia seemed to have been created centuries ago. There was a gap around the contemporary, which things like comics and movies filled. Not that I was a huge Bollywood fan, but I grew up with it around me.

Guernica: When you were studying for your MFA, did you encounter any focus on South Asian art in the curriculum?

Chitra Ganesh: No. There is no South Asia. I took graduate classes in South Asian studies in anthropology. The contemporary art world is still grappling with how to approach and include art made by African-American people as part of the American canon, so I feel that the rest of us are going to need to get in line.

Guernica: What was the response to your early work as an artist?

Chitra Ganesh: The responses were positive—I was really encouraged to do my work from early on—but they were also sort of puzzled as to what it was I was doing. I was working within a figurative representational framework, and there was a sense of reading the painting as a transparency, or truth, or autobiography, which I think is partially the burden of artists of color—or women, or anybody who is representing a so-called minority position. Are you actually telling a true story, or your own story? You don’t just get to tell a story. There were questions: Are you talking about violence against women in India? Are you talking about colonialism? What’s going on with these fragmented bodies? Are these women hurting themselves, have they been hurt? The readings of the work didn’t necessarily conform to my own understanding of mythology, where violence and eroticism and the body and all of these different forms coexist all the time. For instance: Devi Mahatmya is part of a creation story, where the goddess is fighting evil and chopping up all these demons, and from the spilled blood sprouts the rest of the world. The young women who are working with me upstairs [in the museum] were telling me there’s a very similar story in Norse creation mythology. The parallels are uncanny, actually.

Guernica: So your work was initially taken as topical. Did you address those problems, or did you just ignore them?

Chitra Ganesh: I didn’t ignore them. It did make me think more about drawing. And going into an idiom that was maybe not as much tied to representing actual people. It made me think about how to create a visual language, an iconography that would be both about this and outside of this.

Guernica: Have your images of female sexual power brought you any criticism? They can be violent, and grotesque.

Chitra Ganesh: People do wonder why it is like that, and I think the work doesn’t necessarily add up to being something someone wants to hang on their wall [laughs]. I don’t know if you’d call that a criticism, but it has repercussions. Within the Indian, South Asian, and Asian contexts, there’s a lot of familiarity with these stories from manga, with a variety of forms of visual excess, of melodrama, so it doesn’t seem so jarring. My work has never been censored in India, for example. Part of that is because I’m referencing the language, but I’m not making a critique of Hinduism. I may have one in my head, but that’s not what my work is about. I’m more interested in myth, meta-narrative, narrative fractures, and narrative fracturing happening in the bodily fracturing.

Guernica: Tell me more about your interest in mythology.

Chitra Ganesh: I’m very interested in the intricacy and fantastical quality of those stories. They’re just so complex—there’s both resolution and lack of resolution, at the same time. The story can end in twelve different ways—part of it can end well, the other part, somebody just disappears into a fog, or commits suicide, or whatever, and it’s never really taken up again. Having the space to have a lot of unanswered questions and unresolved narratives is really soothing. It’s oppressive to have happily-ever-after all the time. So oppressive.

Guernica: Ambiguity, also, is relaxing.

Chitra Ganesh: It’s productive, too. Internally, psychically.

Image courtesy of the artist and Brodsky Center, Rutgers University

Guernica: That’s probably difficult for some people to stomach: it’s about how you, the viewer, respond to it.

Chitra Ganesh: Yes, how you respond to it. How it may, or may not, mirror your own lived experiences. I know we all watch rom-coms, which are also soothing in their predictability of resolution. But aspects of these stories have been buried in service of a more conservative culture. A friend of mine is doing some work with Grimm’s Fairy Tales, and we were talking about how “Little Red Riding Hood” is really also a story about rape and cross-dressing. It’s been saccharinely watered down and sold at Barnes & Noble as something else, and that’s much more about our culture than it is about that story.

Guernica: Automatic writing has been a central part of your method. Is it still?

Chitra Ganesh: I still write a lot. I’m more interested in moving toward writing stories—thinking about the graphic novel form, and just something more long-form. I did a lot of literary translation in college. I translated [the Latin poet] Catullus for my thesis, I read The Aeneid in the original. Translation is an art. One of the most influential pieces of art in my own practice is Walter Benjamin’s essay “The Task of the Translator.” The idea that you’re always creating another narrative. There’s a disjuncture between the text and the images and my work, which I hope creates a space for a third narrative, a third position, an unexpected reading. But yes: writing has always been a part of how I think through my ideas.

Courtesy of the artist and Gallery Wendi Norris, San Francisco

Guernica: In contemporary art, religion and art are so divided.

Chitra Ganesh: I know, and it’s so funny, because they never were. All existing art was religious until perhaps a hundred years ago. Within that there’s obviously been lots of room for manipulation. I think that’s because our current religion is capitalism. Capitalism has the functions of patronage, commissions, control of content, bestowing of space, elevation of certain artists over others based on how much they pander to people in power, the determination of value of the work, all of it. Capitalism commissions artwork now, the market.

Guernica: Making art itself is an activity that is quite otherworldly.

Chitra Ganesh: The having of the ideas is quite otherworldly. And then the making of the art itself is quite scientific. It’s a combination. Like when I was sewing the thread, which you were watching me do, I was just trying to see what the properties of the thread are: How does it respond to gravity, what is its natural resting point? Doing figurative work or taking pictures, and looking at how light actually reflects and refracts on bodies, or how your perception of something changes based on distance. But I think the getting of the ideas, and having that space to just have the ideas, is definitely otherworldly, and requires a clear mind. Or a clearing—some space in one’s head.

Guernica: Tell me more about the archival materials you selected for the show.

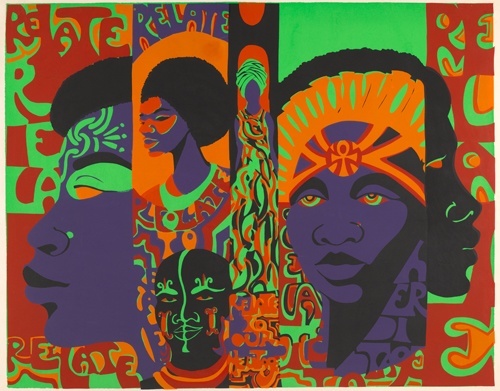

Chitra Ganesh: Aside from “the archive” being a super-duper trendy topic right now, it’s also a central mode of inquiry for me. For many who don’t feel like their experience is represented or mirrored in the outside world, having access to personal or family archives becomes a way of piecing a story together. Also interesting is what goes into an archive, and what remains excluded. It’s interesting to think about connecting the dots within an archive in a different way than linearly or teleologically. It’s a great delight to make art or use language or just have ideas, and put them together in a very unexpected way. Art gets categorized historically, geographically, by medium, not necessarily by concept or repeating imagery, or feminism or femininity. The silkscreen that you see when you first walk in is very colorful. It is “Relate to Your Heritage” (1971) by Barbara Jones-Hogu. She’s part of AfriCOBRA, a black self-determination arts collective from the 1960s related to the black power movement. I don’t think anyone else would put that together with a Louise Bourgeois in terms of the imagery. Like: this is African-American art from the ’60s, and this is contemporary feminist art that is in the canon, and here are some ancient Egyptian figurines. Setting aside some of those modes of organization and reconnecting the dots between these works was really exciting. I also wrote all the captions.

© Barbara Jones-Hogu

Guernica: There’s even an abstract piece by the Japanese artist Shoichi Ida, from 1987.

Chitra Ganesh: The descending triangle. Isn’t that gorgeous? If you look up the Kali yantra—which is a more tantric representation of Kali—you can see that a lot of gods and goddesses are also represented in completely aniconic or abstract forms. There is a very interesting relationship between this extremely representational, visually excessive mode of figurine, the icon, and then this extremely spare piece. One feels very inward and interior, and the other feels very exterior. I’m trying to make sure that the visual connections between the disparate elements are strong enough for the viewer to keep moving through the work. It’s in paying attention to those hundreds of details that the flow of the line will guide an audience through the narrative in a way that will make them enter it enough to engage with it, and perhaps construct their own narrative.

Guernica: Do you still work as a teacher?

Chitra Ganesh: I love teaching. This semester I taught a course at the Rhode Island School of Design on contemporary South Asian art, and I did an honors course at Brown. I’m usually a visiting artist. I love working with younger people. I feel like we need to catch up with them. In South Asian art it’s important to address the fact that the majority of what we see is Hindu, and based in Hinduism, and that it has a social and cultural history. Islam and Muslim culture are often now figured as these outside invaders who came into India, and this is in the service of a more right-wing nationalist discourse that is Islamophobic. And that’s part of the worldwide Islamophobia moment that we’re having right now. You have to mention these things, it’s part of the complexity of the context, of the artwork, just as thinking about whatever historical or social movements are going on in any place at any time are part of it.

Chitra Ganesh: Eyes of Time runs through July 12, 2015, at the Brooklyn Museum.