Mika Rottenberg Still from Bowls Balls Souls Holes, 2014 Video and sculpture installation Video duration: 27 min © Mika Rottenberg, Courtesy of Andrea Rosen Gallery, New York

Mika Rottenberg’s immersive show at Andrea Rosen Gallery relies on our predisposition toward magical thinking: What forces are really at play behind chance? Born in Buenos Aires, raised in Israel, and now living in New York, Rottenberg has a great sense of humor and an astute eye, and over her career (with work in the public collections of the MoMA, SFMOMA, the Guggenheim, and the Whitney, among others), she has created video art that uses joyful, fictional systems to explain the unexplainable. Bowls Balls Souls Holes, the Manhattan expansion of a current exhibition at Boston’s Rose Art Museum, is her seventh institutional solo show in three years. It tackles what she calls “the production of luck,” using the numerical and gambling components of bingo as catalysts. Those familiar with her style will recognize her kitschy, Technicolor world of fleshy women, handmade contraptions, nail art, and wry twists of logic.

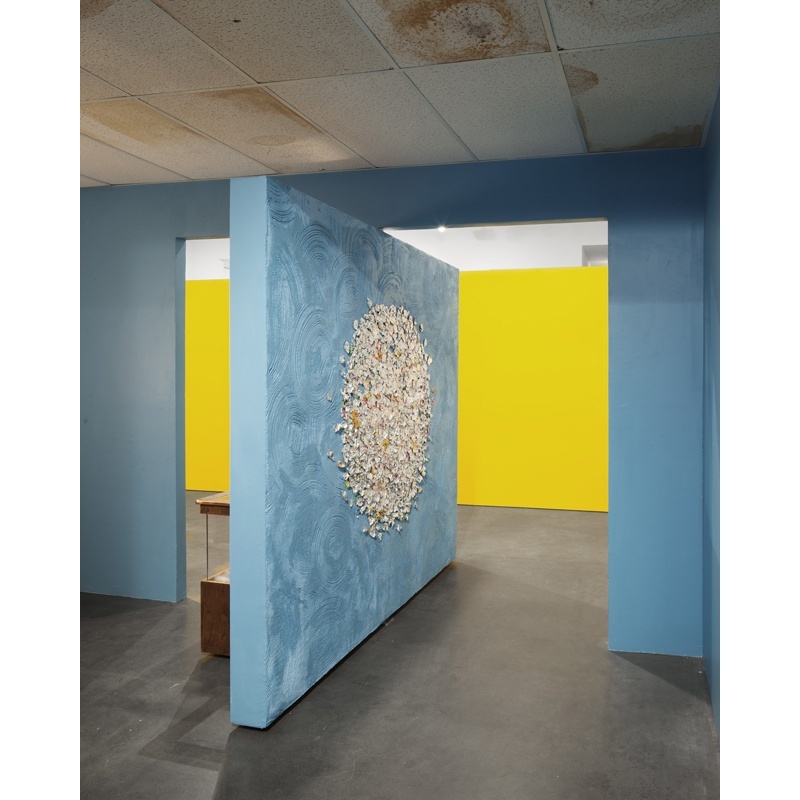

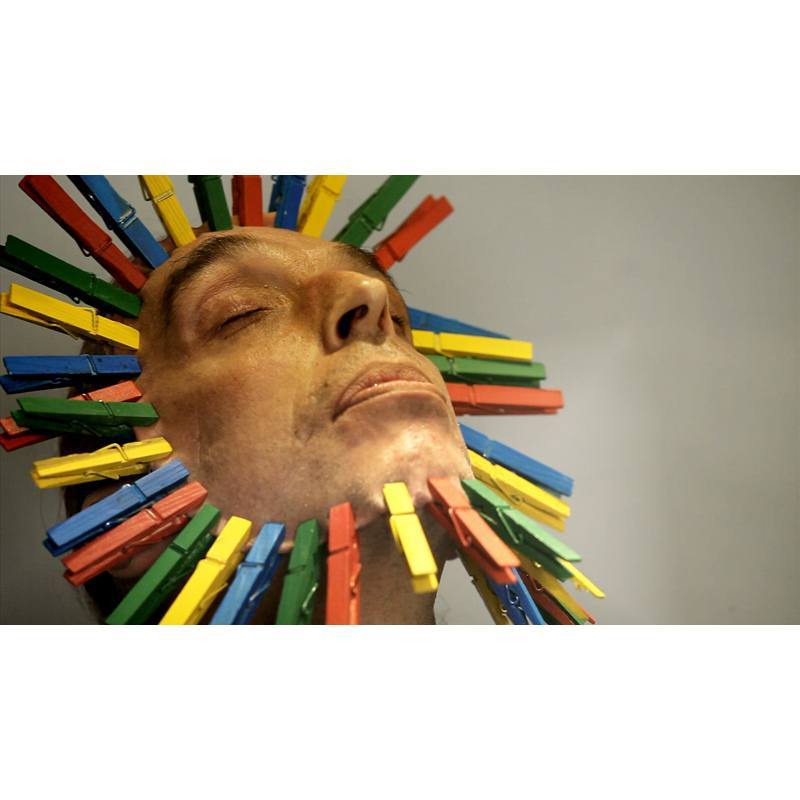

The nerve center of the piece is a half-hour film that screens on loop in a viewing chamber in the middle of the space, but before you see it, Rottenberg is already directing you with sensorial and visual cues. The action begins right as you walk in off the street: affixed to the wall in your immediate sightline is a shabby air conditioner that slowly drips water into a sizzling pan on a hotplate; to the left, a revolving wall mounted with a bingo machine on one side and a large circle of tin-foil scraps on the other folds you into the main area. Instinctively, you walk toward the recorded noise. The film begins with a full moon hovering over a rundown motel, inside of which we find a woman who is preparing to absorb lunar energy—lying on a bare mattress with tin-foil scraps held to her toes with colorful clothespins. She stares at a hole in the ceiling straight above her, and waits for the moon to move across the sky and align itself directly with the gap. Once satiated, she falls asleep. The next day, she gets up and travels via scooter to a vast, underground, yellow bingo hall. She works as a bingo caller, presiding over the spinning balls and reading the numbers to a silently playing crowd. Meanwhile, a mysterious girl in the corner of the hall attracts her worried glances. The girl is overweight, angry, and not playing. She sits slumped against the wall, under the air conditioner, which occasionally drips on her bare shoulder and causes her to sit up abruptly. The two women meet eyes, and a shift occurs. The bingo caller begins to pluck single clothespins from under her desk, dropping them through a round trapdoor that leads to another trapdoor, then another, then another, with gravity or a wooden mechanical device pushing each clothespin along until it falls into a small room and the hands of Mr. Stretch, a thin, fine-boned man who then clicks it onto his face.

We know that the bingo balls are dictating the action, but how and why is unclear, and it is up to us to piece together the sequence of events and chance.

And so it continues: the numbers are called, and Mr. Stretch amasses a full face of clothespins. Subplots surge and recede: the sequence of colors, the flashing bingo machine display, gusts of air from a spinning fan. Through circular graphics that act as portals, we visit the North Pole to witness it melting, and see that the clothespins are here too; although at opposite ends of the planet, the bingo hall and the ice caps are in sync. We know that the bingo balls are dictating the action, but how and why is unclear, and it is up to us to piece together the sequence of events and chance. Gradually, we arrive at the first shot of the moon over the motel once again, and the cycle begins anew. Rottenberg’s affinity for round shapes and their cinematic and experiential possibilities is endless. “In bowls, it’s the circle in particular that leads the plot. I didn’t plan it from the beginning, but noticed it as I was mapping out the shots,” she explains in an email interview. “For example, the boiling glass in the hotel, the wheel of the scooter. Enid, the main performer, was wearing round earrings. When developing the piece, I was thinking about electricity and planetary movement and the globe—those are all circles. When I noticed so many circles in the actual things I was going to film, it created a grand circle between the concept and the material realization of the piece.”

The third part of the show is the back room, in which you find three ponytails flicking mechanically, a glinting light bulb, jars with boiling water, and a round portal in the floor that leads to darkness. After seeing the film, these sculptures are not at all confusing or unfamiliar: they hail from the parallel universe Rottenberg constructed, and to which you now also belong, drawn in by her sonic and visual logic and your own desire to connect the dots. “I use cinema mainly as a way to create and link spaces,” she says. “Like an architect who does not have to obey gravity or physics. With film you can also create psychological space. You can mesh the metaphysical with the physical, internal with external, or create space that operates as an extension of a person.”

Rottenberg uses bingo to hone in on our willingness to accept cause-and-effect explanations for intangible concepts, our susceptibility to rationale (especially if the nudge is funny), and, in a wider sense, our connection to the earth’s movements and systems. Fact is essential to her process—the bingo hall is on 125th Street, none of the featured players or staff were actors, and Gary “Stretch” Turner holds a 2013 Guinness World Record for attaching 161 clothespins to his face—but her impulse to give shape to the nothing is otherworldly, hilarious, and exhilarating.

Bowls Balls Souls Holes runs through June 14.

Alex Zafiris is a writer based in New York.