It’s been two and a half weeks since police officer Derek Chauvin killed George Floyd. In that time, hundreds of thousands of people across 140 cities in the United States, and more across the world, have taken to the streets to protest the matrices of racism that have enabled and emboldened the police to murder Black Americans with impunity.

Huge numbers of New Yorkers have protested since that first weekend, with multiple actions organized by Black community leaders—from rallies and marches to community clean-ups and vigils—occurring across the city’s five boroughs each day. An Instagram account that aggregates information and resources about the protests and their organizers, @justiceforgeorgenyc, has over 186,000 followers on Instagram as of this writing and also maintains a MailChimp listserv, centralizing information on everything from protest locations to street medic training and tips on recording police misconduct.

Such information has been critical: Nearly every protest, before the city lifted curfews and the NYPD adopted a more hands-off approach, saw police pushing, shoving, and sometimes beating peaceful demonstrators. NYPD officers struck protesters with their cars, indiscriminately sprayed tear gas into crowds, and arrested bystanders. And yet the sustained pressure of this worldwide movement, and mounting evidence of the outsized violence done against, rather than by, those protesting, has already won concrete change: Derek Chauvin’s murder charge was increased to second-degree, and the three other officers involved were finally charged as well; Breonna Taylor’s case from March was reopened and Louisville’s mayor suspended the “no-knock” warrants that enabled her death; Confederate monuments have been taken or ordered to be taken down in numerous cities; Minnesota’s City Council voted in a veto-proof majority to disband the police; New York State Assembly banned the chokehold; and the New York State Senate repealed NY Civil Rights Law Sec. 50-A, which shielded police from accountability by deeming their personnel records “confidential.”

Over the last two weeks I have seen thousands of small acts of kindness: Organizers distribute protective masks and chant sheets, volunteers along the routes pump out hand sanitizer, and people in the crowd share bottled water and snacks. I have seen organizers weep as they lead prayers of remembrance, teens grin as we yell “NYPD, suck my dick!” at a bank of cops, and commuters honk and chant as we weave around their cars in traffic. I’ve seen police wearing no PPE (but full riot gear) push past their own blockades to siphon off groups of protesters, and crowds yell “Let her go!” as officers yanked a woman out of a rally in handcuffs. In the context of all of this, many protesters were wary of talking to me. To prevent potential retaliation, their names have been changed or abbreviated. What follows are accounts I collated from notes taken during in-person interviews at various events, or collected over email following them.

Caton Ave., Flatbush, Brooklyn

Saturday, May 30

3:00 pm

Justin: I have been organizing with the movement since 2014. A white dude, I had spent most of my career in the nonprofit sector, and saw that the nonprofit approach to social change was really limited. I ended up doing some of the early work around how to hold police unions accountable and have been deeply embedded in local abolition work since.

There’s so much evidence that the things that keep us safe are investments in communities—education, public health, mental health services, non-profit ecosystems, and mutual aid networks—built outside the infrastructure. But a big reason we can’t do that is so much money and resources go to the police force and its cousins, jail and prison.

When this most recent set of circumstances around George Floyd caused a reaction, nationally, I made sure to get out in the streets because I was angry. I was out for the first two nights of protests—Friday the 29th and Saturday the 30th.

Friday I went to Barclays and marched to Fort Greene, over to the 80th precinct. I was part of the group that got badly beaten over by DeKalb Avenue. I have been to a lot of protests where there was a police presence, but this was different: They charged me with night sticks, I watched them beat hundreds and hundreds of people. Frankly, the police were behaving like a military—they were actively trying to secure a block, they were using military tactics and military gear, and so I was like, this is going to be a military engagement with protesters.

On Saturday I went to the Equality for Flatbush rally. Toward the end of the evening, a bunch of the groups split off because police kettled people in Flatbush. By 9, 9:30 there was a significant standoff between protesters and police at the corner of Church and Bedford. There were fires on a few corners—it was a real faceoff between cops and kids, and cops kept charging and putting them back. At some point NYPD sent in significant reinforcements and drove people further east on Church Ave, at which point I was one of twenty or so people, and they made a final charge and arrested and beat all of us.

It was intense, I’m not going to lie. A lot of people ran. I put my body in the way, didn’t want kids to get arrested. A lot of people got swept up in these mass arrests who weren’t even protesting: two Black Americans from Flatbush were at a corner shop and they were indiscriminately tackled and arrested just for being nearby.

I was arrested with five people and taken to 1 Police Plaza. I counted seventy people in a small cell. I didn’t ask about everyone’s charges but I would guess a large majority were there for protesting. They arrested us without reading our rights—they said I was charged with one thing and when I left I was charged with a different thing entirely. I spent the night in jail, I was bleeding on my legs and arms. They took away our PPE for the evening and they told people they were “insignificant” and “didn’t matter,” which I found…interesting, given that the protest was insisting that Black lives matter.

Zakiya: I hadn’t intentionally gotten within six feet of a stranger in nearly three months, and as my boyfriend and I approached the crowd waiting outside Prospect Park for the speeches to begin, I’ll admit I felt apprehensive. But as more and more people of all races gathered, holding signs and playing music, my fear of getting too close to someone and contracting coronavirus was replaced by joy and relief.

It didn’t take too long for these good feelings to be replaced with more apprehension—and irritation—when someone in my group pointed out a few police officers standing on top of the building directly behind us, looking down on the people speaking. Naive as it sounds, that was the moment I realized, Oh shit…this could get real. I’d never had that feeling at any of the other protests I’d been to—not the marches protesting Trump, nor the March for Our Lives or the Muslim ban protests.

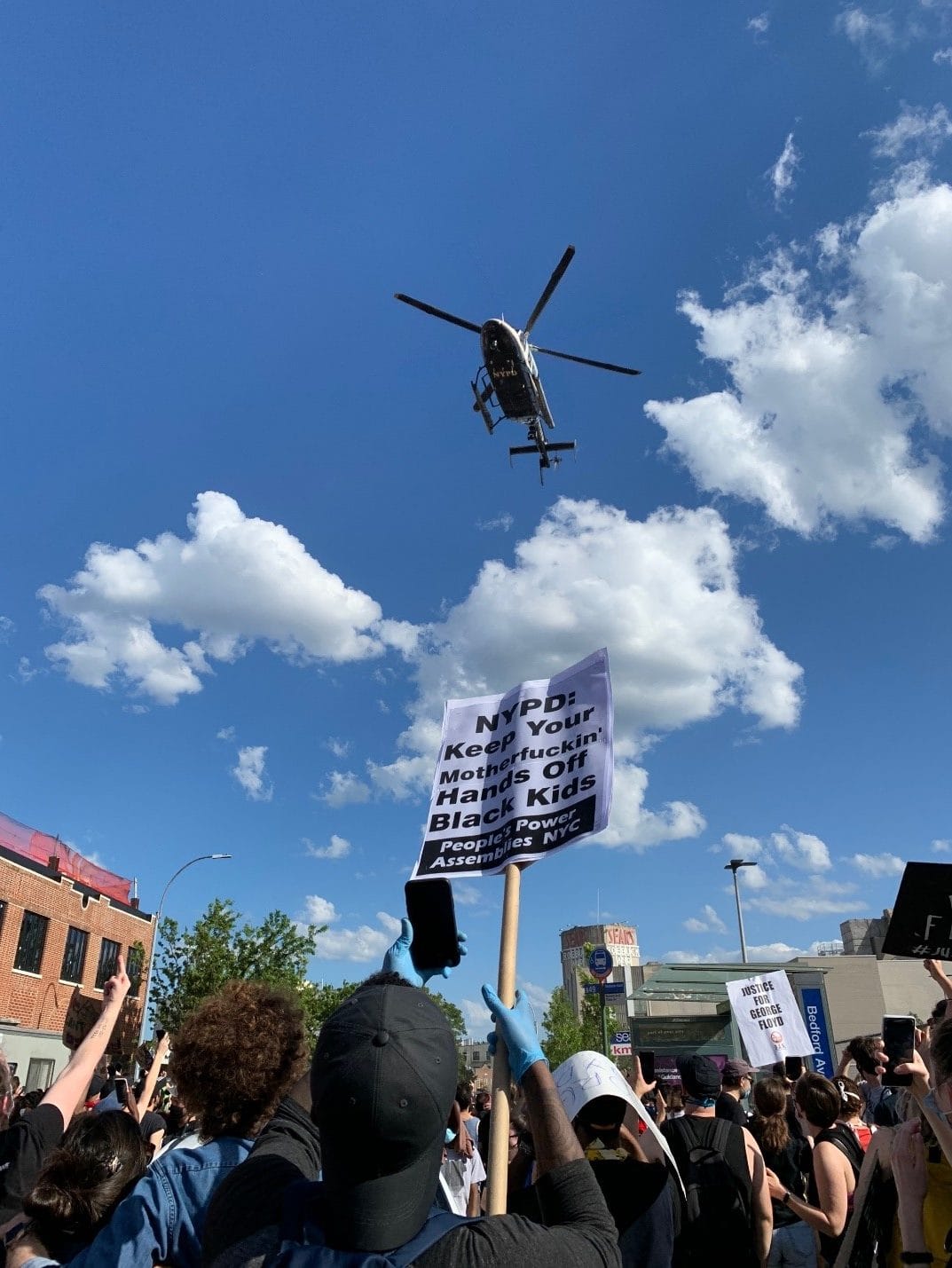

Still, it was one of the most cathartic experiences I’ve ever had. I felt purposeful and proud—I needed to shout and clap and chant with strangers and friends I hadn’t seen in months about how pissed off I was. But I couldn’t shake that earlier feeling of the cops standing on that building behind us, watching our every move, which was solidified later on when a police helicopter hovered close enough to us that we could see the face of the cop flying it. That was terrifying enough, but it got worse when the helicopter faked us out, zooming toward us as though it were going to land on us. It got so close that, for a few seconds, I could feel the wind of the propellers and the dust it was kicking up in my eyes. And in that moment, I wondered, Are we going to be shot?

Courtney: Once we started marching, it became clear that not only did we have several officers posted along our path and walking along side us, but helicopters were monitoring us in the air, too. It wasn’t long until the helicopter directly above our section started to get lower and lower. It was so close to us that people started running, assuming the pilot was trying to land on us, and then he started spinning and dipping the tail end of the helicopter as if he was trying to hit us. But we stood our ground and then eventually moved in the opposite direction, which we quickly realized was the goal of their helicopter stunts: A few blocks later we came upon hundreds of NYPD officers in head-to-toe riot gear, blocking our path, with more were pouring in from the side streets. I am white, and while I have long been aware of the violence and intimidation tactics people of color in this country have experienced from law enforcement, this was my first time experiencing it myself, and it was far more than unnerving—it was terrifying.

Stonewall Inn, West Village, Manhattan

Tuesday, June 2

5:00pm

RV: First and foremost: fuck the police. Today the cops haven’t been so violent yet, but just their presence makes my skin crawl.

When police killed Tony McDade in Tallahassee, my community was mourning. Tony’s murder was preceded by transphobic violence inflicted on him by his community. Someone called the police on Tony for defending himself, and then the police killed him. As far as we know, Tony is the first Black trans man killed by police, and no one except for trans folks had been lifting up his name. We were pissed and heartbroken.

As a trans person, it was important for me to come out and say their names and rage alongside my community. For years I’ve been organizing and building community because I deeply believe that isolation will kill us. And I knew, especially with the isolation of COVID, I couldn’t, that we couldn’t bear the rage and heartbreak of these violent deaths alone.

Too many people are shocked at the police brutality that’s happening right now. It’s like folks haven’t been listening to the generations of Black folks decrying police violence. We shouldn’t be shocked when the police beat people with batons in broad daylight. We should be outraged. And more importantly, as organizers, we should be prepared for this possibility at any moment, because then we can prepare for our reaction and our own safety. For example, today we have comrades off-site who have safety plans for protesters. These comrades know who to call in case someone gets arrested or injured. These precautions help us keep each other safe, and this is essential because we know the cops will never protect us today or any other day.

I hope we defund the NYPD. I hope we can realize abolition here and now. I hope we learn to say all the names of those who’ve been killed or disappeared by state violence. I hope that folks can stick with the fight. I hope we’re in a moment of radical transformation where people can breathe deep the possibility of all that we could accomplish together, and then I hope we put in the work. It’s a lot of fucking work. It’s self-work, unlearning all the ways we reproduce harm and nourishing our imaginations of how a more healed version of ourselves might engage. It’s communal work of caring for one another. It’s societal work of creating new models for justice that do not rely on policing or locking people in cages. It’s practical work of growing food and teaching children and coordinating calendars and making art and building new tools. It’s so much work, but I hope more of us commit to doing the work so that we can move forward and shape change together.

The state wants us dead or disappeared. They don’t want us to take up space, tell our own stories, or remind each other of our power. We must take every opportunity to rage and scream and fight and celebrate and love and build and change together.

When we’re together, everything feels possible.

Crown Heights, Brooklyn

Thursday, June 4

3:00pm

Brandon: I’m out here today because I’m a Black male and a med student, and I’ve seen so much institutionalized racism in public health. This is my first protest so far, because the medical community—my program—didn’t want us going to these protests because of COVID-19. For a few days I was signing petitions and donating, but I felt restless. We felt it was important to show up, in our scrubs, because we want the medical community to step up. Already there are these food deserts—Black people have less access to proper food—we are disadvantaged when it comes to getting proper medical treatment, education—our lives are already at stake because of racial disparities. That’s why I wrote this on my sign: “BLACK HEALTH DISPARITIES IS A PUBLIC HEALTH EMERGENCY.”

Jane: It had been roughly three months of quarantine, and we’d been paying attention: The news said over and over that Blacks and Latinx people were disproportionately affected by COVID-19. Then we saw police targeting Black people, and we couldn’t just sit back and watch. Being a doctor, my voice matters—I want to speak out about the racial disparity not just in the police force but in public health.

The police were created to catch runaway slaves—slaves were considered property. So the police force was designed to protect property, not people. It’s supposed to be our job—cops, and doctors—to protect people. People say “a few bad cops,” but it’s beyond that. This system was created intentionally, through racism, and it’s our job to speak out against it now, to get our representatives to enact change. We elected them, so it’s on us! We have to get them to do their jobs. As doctors, we do ours! We take an oath—do no harm. It is our ethical duty. I mean, your job isn’t secure if you do something wrong. We don’t carry weapons, but we get review boards for how we carry out procedures—we can lose our licenses if we mess up. We want cops held to those same standards. We took an oath, and they take an oath, but cops aren’t held accountable.

Brandon: We have lethal capabilities as well, but unlike the police, we feel the consequences. This code of ethics is instilled very early on—we have classes where we learn about implicit biases, etc. Do cops take ethical classes? We take ethical exams—do they?

Anon @artistsforgeorge: For the first five days of protests I did nothing. Like so many people I was horrified, angry, sad…and at a total loss for how to effectively move forward. Or, more importantly, how I could meaningfully contribute.

I should point out that I am not a US citizen. I also have my family here with me in the US, so the idea of getting arrested and having our life here thrown into jeopardy just didn’t make sense. I haven’t been to any protests before this—I actually gave them quite a wide berth!

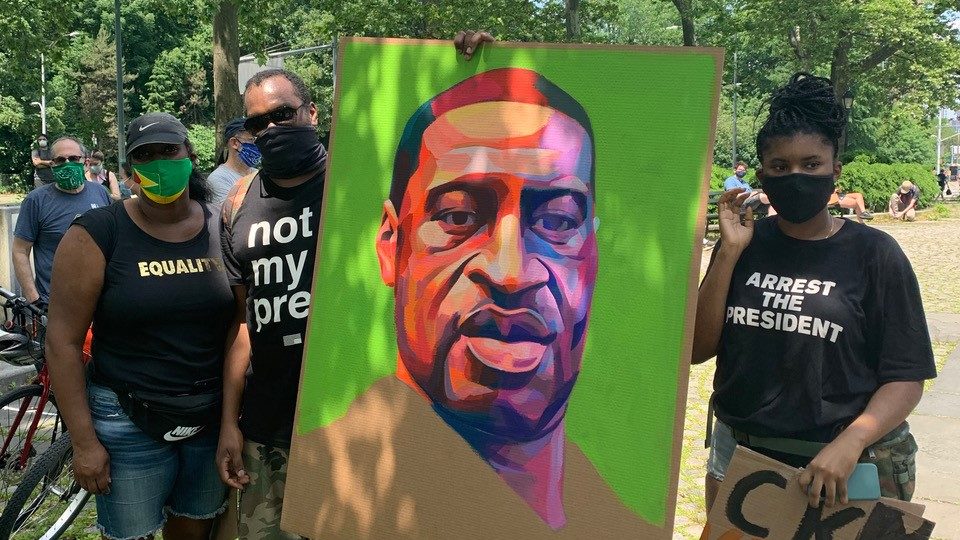

At some point I read one of those social media memes that was going around, talking about the revolution having many different lanes, and that we all contribute in different ways, and there was mention of art activism. That clicked with me and I realized that I should channel what I was already doing in the studio every day into something that could contribute. And as much as I wanted to do something that would be meaningful to the protests, I also wanted to do something that felt meaningful for myself…to find a way to work through the anger and sadness I was feeling.

So I decided to paint a portrait every day and drop it off with a protester. The repetitive labor is a daily period of time that I get to meditate on George Floyd, grapple with his every feature and ultimately make something that honors him. And giving that to someone random for free, feels very much in the spirit of this moment, when we need to rally for people we’ve never met.

About two days into the project, Lane Sell from Shoestring Press offered to print smaller editions of the previous days’ paintings, which he, too, mounts as placards. So now we hit the protests together each afternoon and get our works into the hands of protesters.

There is also importance, I think, in doing this anonymously. The response on our Instagram page has been amazing and already we are having our costs covered by small donations from people who’ve seen the work. But I am mindful of keeping this purely about George and not inserting myself into the narrative.

I hope that this turns out to be the moment it seems to be. Firstly, I hope that white people begin to truly educate themselves about racism and what it means to be Black in America, and that some healing can begin. Secondly, I really hope that policing in the US can be overhauled from the ground up. I’ve always believed that many cops are the kinds of men that would be in jail if they didn’t have a badge to hide behind. It’s a line of work that attracts the worst violent, toxic males, and that becomes the dominant culture in the police force, not just in the US, but all over the world. People who want to beat the crap out of other people, should not be put in a position to do so. And not recruiting those kinds of candidates would be a start. Disarming cops would help too. And disabusing them of the belief (and apparently the reality) that they are above the law seems like a no-brainer.

Grand Army Plaza, Prospect Heights, Brooklyn

Saturday, June 6

3:00pm

V: I wanted to provide supplies to the protesters because I hadn’t taken part in any marches yet due to the pandemic. I’d had an internal struggle about it—I wanted to stay safe for my work—and so I thought, this is something I can do. My plan was just to collect supplies to disperse before the marches leave, but at some point I just took up with the crowd, COVID out the door. My experiences of the protests have been peaceful, with moments of fear—I’ve watched cops pull out their batons, my friends have seen people collapse.

I decided to come out today specifically because it’s supposed to be really hot, and a lot of people I know who are still working through this—my demographic—said today would be the day they came out. I’m a caretaker, so I’m really trying to keep this stock load up and keep people hydrated.

And donations keep coming through—we raised $2,000 in a day and were able to get tons of safety kits together. At first I was doing this on my own—I’m not a part of “Protect Protesters”—but we’ve realized there are a lot of us, and we all found each other online so we can coordinate.

This is one for the history books; it’s incredible to see everyone rallying. I hope we continue to come out for BLM, to listen to what they’re doing and support.

Barclays Center, Prospect Heights, Brooklyn

Monday, June 8

7:00pm

J: I’ve been to at least three or four protests now, because shit has got to change. Some people can’t be in the field, so I felt like it was my turn to come out. I had been alternating between donating and petitioning, and now I’m on the street. My experience with the NYPD has been…not great, but nothing too crazy because I haven’t stayed out past curfew. I live with my parents and I have to get home to East Flatbush. [The crowd around us begins chanting “Quit Your Job!” to the cops flanking our route.] I like this one—“Quit your job.” We need to let them know their presence isn’t needed. They uphold an unjust system, and we don’t need them. Abolish the police—no, fuck the police! And fuck de Blasio!