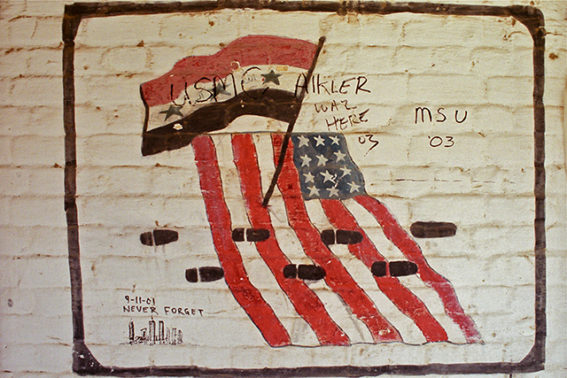

Graffiti from a Marine unit on an abandoned Iraqi military barracks shows the Iraqi and American flags in 2003. Photo by Benjamin Busch.”

By Nissa Rhee

Marine Corps veteran Benjamin Busch had no idea what he would find when he returned to Iraq in 2013, ten years after he had first arrived in desert digital camouflage. The commander of a Marine Corps Light Armored Reconnaissance company, Busch had served as a provisional military mayor in the early days of the US invasion. Now, he was going back as a tourist, armed only with a camera and a notebook.

“We were essentially marooned near the parched Iranian border for months [during the war] charged with security, infrastructure and governance of scattered rural villages and I focused on one town in particular named Jassan,” Busch told me in a recent e-mail conversation. “It was small enough to remain invisible to the news for a decade afterward and I wondered what had happened to it.”

Despite the danger, a number of vets return to their former battlefields each year, driven by questions about a war that ended only in name.

Of the 1.5 million Americans who served in Iraq, only a small percentage has returned since the US military mission ended there in 2011. With the rise of ISIS and sectarian violence, the State Department strongly discourages all but essential travel and warns that “U.S. citizens in Iraq remain at high risk for kidnapping and terrorist violence.” Yet despite the danger, a number of vets like Busch return to their former battlefields each year, driven by questions about a war that ended only in name.

For the last two years, I’ve been covering the return of American veterans to Vietnam, a country where the US fought another war plagued with misgivings and defeats. While four decades separate the experiences of the vets who fought in Vietnam and Iraq, their reasons for returning sound remarkably similar. War left a profound impression on their lives, and they returned to make sense of those memories and to better understand their place in history.

Tens of thousands of American veterans have gone back to Vietnam since the fall of Saigon forty years ago this month. The Vietnam they return to is in many ways unrecognizable—military airports are now strip malls and napalmed mountainsides are covered in rubber trees and paved highways. And to their amazement, the Vietnamese they once considered enemies, embrace them as friends.

Bill Ervin, a Marine vet who now lives in central Vietnam likens returning to visiting your old schoolhouse: “Things don’t look as big as you remember them.”

These vets talk about how healing their trip back to Vietnam is, how “it starts to rewrite some of the tapes” that have been playing continuously in their minds since they left the war four decades before. Bill Ervin, a Marine vet who now lives in central Vietnam and runs his own travel agency for veterans, likens returning to visiting your old schoolhouse: “Things don’t look as big as you remember them.”

In Iraq, however, the schoolhouse looks much the same. In the four years since the American war formally ended there, an estimated 35,000 Iraqis have died from violence and two million people are now internally displaced. The challenges that American troops faced during the war largely still exist in Iraq and there is no happy ending in sight.

“In 2003 the village leaders would say, ‘It will take us ten years to make democracy work here,’” Busch recalled. “I had seen new ideas in their infancy, a people exposed after a prolonged isolation and I wanted to find out what ten years had truly delivered after our legacy of mistakes. When I was in Jassan in 2013, the village leaders told me: ‘It will take us ten years to make democracy work here.’ And then the Islamic State invaded.”

In Vietnam, the American war is the domain of history museums and the cemeteries scattered throughout the south. With the fighting ongoing in Iraq, however, the American war is something that returning veterans must face head-on, without much room for reflection.

For some, that means returning as a mercenary. Patrick Maxwell, a twenty-nine-year-old Marine vet, recently told the The New York Times that he decided to volunteer as a fighter with the Kurdish pesh merga after watching ISIS militants taking over Iraqi cities on the news. He said that he “never saw the enemy” during his 2006 deployment in Anbar Province, despite being shot at daily. Returning to Iraq became his second chance.

“I may not be enlisted anymore, but I’m still a warrior,” Maxwell told the Times. “I figured if I could walk away from here and kill as many of the bad guys as I could, that would be a good thing.”

Maxwell ended up leaving the Kurdish security forces and returning home, however, after seven disappointing weeks on the frontlines. He saw little fighting in what amounted to a standoff and was discouraged by the “politics” of the conflict.

“There is life after war, but you have to find it,” Vietnam vet Suel Jones told me when I visited him in 2013 in Da Nang, just a few miles south of where the first Marines landed in Vietnam in 1965. After earning two Purple Hearts in the Marines during the war, Jones spent years wandering the US and working odd jobs before settling down in a remote Alaskan cabin, sixty miles from the nearest town. He returned to Vietnam in 1998—three decades after arriving as a soldier—and had been living most of the year there since.

“I was a killer over here and I had to find out who I was as a human being.”

“You’re not going to find what you’re looking for fighting another war,” he said. “You’ve got to be able to step away, look back, and ask, how do I live my life? I was a killer over here and I had to find out who I was as a human being.”

So can Iraq vets look back by going back as Vietnam vets have so successfully done? For Busch, the answer is yes.

“I don’t believe there is a closure to a war experience. A reckoning perhaps, but not an end,” Busch said. “I found out how insignificant all my efforts there had ultimately been, but that I was not yet forgotten. I found that a village in Iraq was familiar to me, as if it were somehow like the small central New York town I grew up in.”

“I am in some ways Jassani now,” Busch continued. “I thought it would just be a place I had been like any other in my life, but I am more attached to it than where I live now in Michigan. The war made me pay close attention to everything and for that reason I saw Jassan with more magnification.”

The fighting in Iraq will not continue forever. When the country is at last at peace and safe travel is possible, veterans will inevitably return in large numbers, just as they have gone and continue to go to Vietnam. The war has made Iraq part of them. Whether things will look as big as they remember them being will depend on just how the conflict develops there in the years to come.

For his part, Busch says he plans to go back to Iraq again later this year. He still has questions, and he has to go where the answers are.