H

e chose the darkest part for us

between the campsite and communal fire.

Said this was just the place to teach us

night vision, which he’d perfected

as a Reservist in the jungles

of Florida, a simulated drop

behind enemy lines in ’Nam,

where survival depended on following

the footfalls of shy, nocturnal beasts.

Or picking out the metal catch

of a mine in the shuddering moonlight—

which, in these New England woods,

he translated into spreading roots

—splayed—tendons of hands—

across the paths. The sniper’s mark

was a spinner’s web at temple level.

Our task was to set our sight

on the sightless part,

then wait for the pupils’ dilation,

trusting the way to reveal itself

out of the barked periphery.

For some time, we stumbled—

horses riding into blinders.

The path we pretended to see

was only his voice, which we followed

through red oaks, scuffing

our boots on swaybacked stones.

When it happened, it was exactly

like looking through a stereogram,

the snow-white static of this

perceived world falling away,

the trails of badger and deer,

litter-drag of porcupines, the retreat

made implicit to the un-learned eye.

Years later, I’m at the sudden funeral

of his wife. He wears his grief

like a new shirt, self-consciously,

and I suppose there isn’t any other way.

I’m one of the scrupulous mourners

who wait for him to cross the mortuary lot.

That is when I notice

his slant-faced approach.

He is not-looking for the way,

trying night vision in broad day. I watch

him watch the static fall away.

Listen:

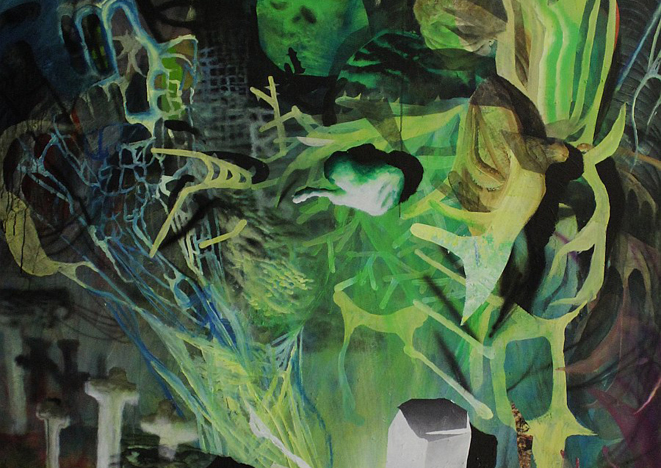

Feature image by Julius Hofmann. Courtesy of the artist

Click on the image to enlarge.