Right after I injected heroin, I always made a beeline for Clark Street. I’d leave my sparse one-bedroom apartment, take the elevator down to the marble lobby, and go out the double doors. My head pulsing with warmth, I’d light a cigarette and walk among a swarm of pedestrians.

It wasn’t that I enjoyed this ritual; it just felt like a necessity. Walking down the main drag of Lincoln Park in Chicago, I was trying to solve the paradox of heroin addiction: everyone I knew who died of an overdose had done so when they were alone, but maintaining a heroin habit meant that I was alone most of the time. I was hiding from friends, from family, from the police. I figured that if I ever overdosed — and somehow, in my five years of opioid use, I never did — it would be best if it happened in public, where a Good Samaritan could call for help. I was trapped somewhere between worlds, hiding while praying to be found.

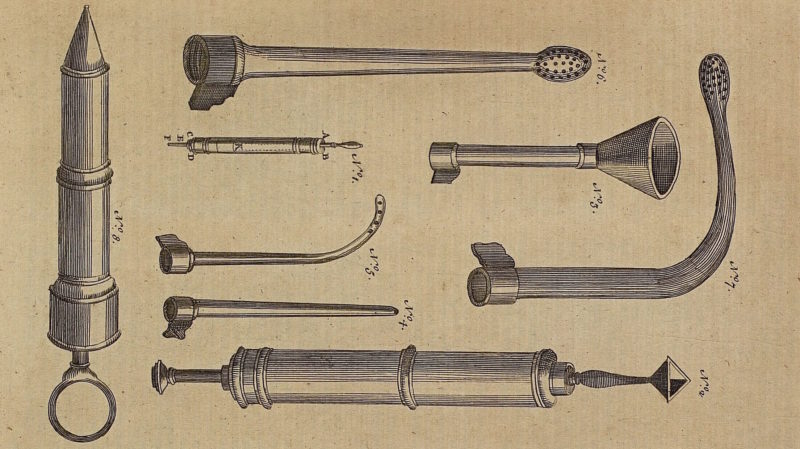

Much later, I learned that opioid overdoses could be reversed by a drug called naloxone, an “opioid antagonist” administered via a simple intramuscular injection or an even simpler nasal spray. Antagonists blast heroin and other opioids off of receptors in the brain, rapidly restoring breath and life to the unconscious body. There are activists who make it their life’s work to get naloxone into the hands of the masses, to keep people like me safe. They are Good Samaritans equipped with the power of Christ bringing Lazarus back from the dead.

Naloxone has lately been enthusiastically — and uncharacteristically — accepted by the political establishment. Every single state has passed laws making naloxone easier to access. In 2018, Dr. Jerome Adams, the Trump-appointed surgeon general, issued an advisory that urged the public to carry naloxone and ended with the emphatic lines “BE PREPARED. GET NALOXONE. SAVE A LIFE.” The antidote can now be obtained from vending machines, without a prescription. It’s advertised on highway billboards and in public service announcements on local TV. One brand name, Narcan, has entered colloquial speech and therefore public consciousness. Yet overdose deaths have hit new heights. In 2020, more than one million doses of naloxone were distributed by harm reduction groups alone — and more than a hundred thousand people died from overdoses, the most ever recorded in a single year.

Manufacturing shortages, distribution bottlenecks, and soaring prices set by pharmaceutical companies mean that there is still not enough naloxone to go around. Then there’s the loneliness of heroin addiction, that paradox I could never solve. Naloxone’s key ingredient, its mechanism of action, lies beyond chemistry: for naloxone to save a life, people have to show up for one another. In her book OD: Naloxone and the Politics of Overdose, the historian Nancy Campbell describes the drug as a “technology of solidarity.” During an overdose, the user is unconscious and cannot revive themselves. But even as naloxone has gained acceptance, addiction has retained its stigma and its criminalized status, locking many drug users in unreachable isolation.

When I had no one, I walked down Clark Street — a risky, fraught, fallible endeavor to stay alive. My aimless walks were like trust falls, revealing a utopian hope about what we could expect from each other when in need. The efficacy of naloxone depends on this hope. In my desperation, I understood something about solidarity.

Now, a decade after those walks, though I’m no longer using, there’s always naloxone in my backpack. I try never to leave home without it. Someone beside me might be in the place I once was, alone in public, banking on the humanity of strangers. Now I can be the one who shows up. And I’ll be prepared.