Invisible lines divide Nairobi in absurd ways. Some correspond to the racial divisions of Nairobi’s apartheid past, when Black men were forbidden from moving through the city without wearing a pass around their neck and Black women were prohibited from living in the city altogether. There are entire apartment complexes owned by third- or fourth-generation Asian families who refuse to rent to Black residents, and predominantly white neighborhoods with their own schools and clubs hidden behind steel gates. Other lines reveal class divisions. Informal settlements made of corrugated iron sheets gleam in the sun, and many four-lane highways have no sidewalks or bicycle paths, reflecting the government’s ambition to pretend that the vast majority of the city’s residents don’t walk everywhere.

Even the word Nairobi has a history of division. The city’s name is stolen from the Maasai people who today inhabit Southern Kenya and Northern Tanzania. Before colonization, they marched freely across most of the savannah, leading their enormous herds of cattle toward the greenest pastures. Historians say that the city’s name is a bastardized form of enkay nairob, or a place of cool waters, referring to the swamps, small rivers, and tributaries that once criss-crossed the place but are now buried under the foundations of various high-rises, forgotten behind the fences of poorly planned residential communities, and hidden under mounds of garbage in the city’s informal settlements. Years after they moved their capital from the drier trading post of Machakos to this oasis, British colonialists dubbed Nairobi “The Green City in the Sun” and then deployed forced and indentured labor to develop the lush, mosquito-ridden swamplands into a railway town.

Today, Nairobi’s green is under assault from a government that chops down trees to make way for expressways and half-empty apartment complexes. The Maasai were beaten back to drier territory, and the only legacy of their presence is the city’s name and the occasional herds that stray into the city when drought consumes the countryside. The central business district bears witness to both the hopes of independence and their implosion in some of the most striking examples of African modernism, choking in litter, ill-advised renovations, and garish paintwork. Matatus, privately owned minibuses, are loosely organized by route numbers that hint at what used to be a highly organized public transit system now dissolved into chaos and cartels. Everywhere you look, the city’s whispers about what it was and what it might have been are drowned out by the screaming disappointment of what it actually became.

For all the fertile ground that its complex and rich history provides, Nairobi is not the first place that outsiders think of when they consider literature from Africa. Even nearby Somalia, still ravaged by over a quarter century of war, hosts at least seven literary festivals a year, and Kenya’s western neighbor Uganda is home to the internationally acclaimed Writivism festival. But besides the Nairobi Book Fair, a trade fair for the country’s publishers, Kenya hosts no regular English literature festivals. Literature in Kiswahili, the country’s other national language, is even rarer, to say nothing of writing in the other forty-plus languages spoken in Kenya, even while laws on local content demand that at least forty percent of the content on local media be in languages other than English.

Kenya’s literary dwarfism is partly a result of the virulent anti-intellectualism of the longest running regime in the country, the period from 1978 and 2002 when Daniel arap Moi was President. Those years were characterized by arbitrary arrests, detention, and the exile of scholars including world-renowned author Ngugi wa Thiong’o and Micere Mugo, both former professors of literature at the University of Nairobi. Popular fiction was not spared the assault, as writers such as David Mailu had their works banned for their sexually provocative subjects. As a result, Kenya developed a reputation as a literary desert, with only a handful of writers like Meja Mwangi and Marjorie Oludhe Macgoye evading the heavy hand of censorship by publishing books that could at least be taught as assigned reading in schools.

But the government did not stop merely at censoring books: the Moi regime was determined to use every tool available to make publishing unviable. Two of Nairobi’s flagship independent bookstores were on the wrong side of high-profile litigation designed to punish them for making controversial books available to the mass market. One such book was a biography of former US Ambassador to Kenya Smith Hempstone that made several sensational claims about the assassination of Robert Ouko, a former Minister of Foreign Affairs. Even today, Nairobi’s public libraries are not allowed to show patrons newspapers from controversial dates in the country’s history, like the day Ouko’s body was found. Books in Kenya are taxed as luxury items, incurring surcharges of up to 60 percent. This history explains the broad contours of Kenya’s reading culture: covert as publishers avoid censorship, difficult to measure because of the preponderance of second-hand sales, and officially dominated by the sale of self-help books like Ben Carson’s (yes, that one) Think Big, which allow for public performances of neoliberal intellectualism without actually pushing the reader to think independently.

How do you fictionalize a city like this? How do you tell stories of a place where the government saw stories as an enemy to be conquered and manipulated? How do you represent a history of conquest and political violence without provoking a backlash? How do you ensure your own economic survival as a writer in a country where the government is determined to make writing fail? For Kenya’s fiction writers, the answer has been to hide their observations behind heavy-handed moralizing in books that can be sold as assigned reading for high school students. Nairobi’s fiction is descriptive and anthropological: a substitute for official archives for a city where records are censored according to the whims of the current regime. Some writers hid their work in the city’s unofficial language, Sheng’, a patois that testifies to Nairobi’s diversity and dynamism. But the city is tormented by the ghosts of novels, short stories, and plays never written as the authors left the cultural scene in favor of more respectable pursuits.

Thankfully, a generation of fiction writers is coming together to tell Nairobi’s story in its own terms, and with its own language and cadences. Nationally, Ngugi wa Thiong’o remains the most successful fiction writer, and lately Yvonne Adhiambo Owuor has established herself as the sharpest and most lyrical chronicler of the national condition. But there is also a generation of writers focusing on Nairobi, telling the story of its lost generation—those who grew up under the weight of Moi’s censorship and oppression. These are the stories of the 1982 attempted coup and its detritus; of middle-class neighborhoods that collapsed into disrepair as the economy imploded; of young men from the countryside who came to the city in search of fortune only to be consumed by its informal settlements; of people who learned how to whisper political opinions into books and music so that a government that still veers towards authoritarianism cannot hear.

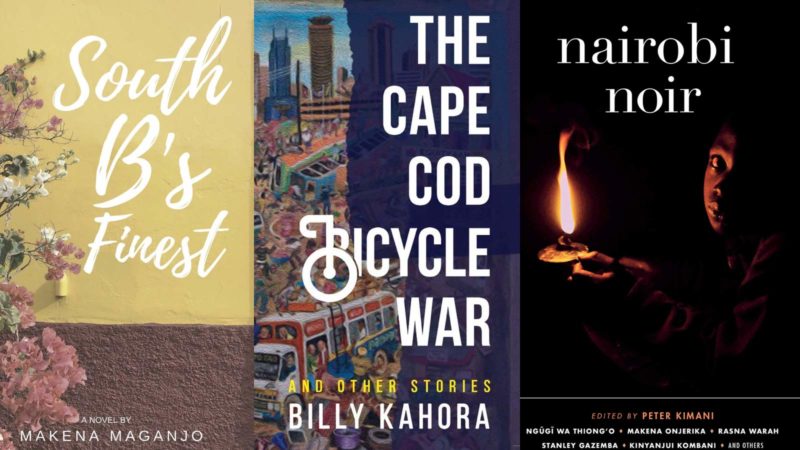

Makena Maganjo’s debut novel South B’s Finest, Billy Kahora’s short story collection The Cape Cod Bicycle War, and Nairobi Noir, a collection of crime stories edited by Peter Kimani, all published this year and last, are insightful additions to these new Nairobi narratives. Of the three authors, Maganjo, who spent her childhood in Nairobi’s South B neighborhood, succeeds the most at capturing the rhythms of quotidian life in the city. There is no Nairobi without Sheng’, and for the author attempting to tell an authentic story about the city, mastering the inflections and class variations of the patois is the easiest way to signal that you see the city completely. Sheng’ is, after all, a ligature that unites this highly fragmented town without hiding away from its class and age divisions. For example, in this city of just under five million inhabitants, a public transport minivan can either be a matatu, a mat, a jav, or a mathree, depending on where you live and how old you are. Whichever word you use, though, Nairobians will know what you mean. Maganjo goes the furthest to establish what residents know to be true—that there is no Nairobi without Sheng’—in this story of a middle-class neighborhood that loses its pretensions as the economy around it collapses and residents resort to ever more drastic decisions to preserve their delusions of affluence.

South B’s Finest is the story of one of Nairobi’s estates, meaning not the stately homes or shabby public housing evoked by that word in British English, but rather collections of single-family homes built by the same developer. In the late 1980s, the residents of these estates were middle- and upper-class professionals who represent the first generation to be born and raised in the city. But by the end of the 1990s, the Kenyan economy had collapsed, and the polished veneer of estate life had faded. There are scandals and secrets, and the novel toggles between the past and the present to hint at how personal dynamics collide with deteriorating politics to pressure people into ceding parts of their humanity just to survive. Trust fades, the walls get higher, and neighborliness is lost in the rush for survival. “Nairobi’s beauty was in its alchemy,” Maganjo writes, “how it conjured riches from what had always been a swamp. [And] in the 1990s…to be a Nairobian was to be struck by the ravenous lunacy that plagues only the alchemist.”

Kahora’s short story collection is more a testament to how Nairobi’s fluctuating fortunes collide with urban masculinities. Like Ngugi’s work, the stories here examine how men experienced both colonization and authoritarianism in the postcolonial state. Kahora’s stories follow the Kenyan middle-class man as his mental health fails, as he leaves the country to pursue the academic ambitions that a collapsing public education system can no longer accommodate, and as he navigates desire and sex in a neoliberal state where everything can be a commodity, including marriage. The similarities with Ngugi run deeper still: most of the central characters in Kahora’s collection are also Kikuyu, a choice that perhaps reflects Kahora’s autobiographical instincts but sits uneasily in the context of the city’s history.

The myth of Nairobi’s middle class has always been the promise of a post-ethnic society: because we all have roots somewhere else, none of us can lay claim to owning the city. This myth was severely undermined by the 2007–08 post-election violence, which brought ethnonationalist fighting to Nairobi’s doorsteps for the first time. Since then, ethnicity has remained tangled up in unresolved questions about the integrity of the state and proximity to power. Who gets to be a writer? Who gets to tell stories and label them universal? Who gets to center their experience in the way the city’s story is told? Yet Kahora, unlike Ngugi, does not see tradition or a return to the ethnic as a way to salvation. He sees unqualified or uninterrogated allegiance to tradition, even the traditions that we build for ourselves in the city, as a sort of prison that the protagonist must be wary of.

Given the sheer number of voices it contains, Kimani’s anthology should in theory represent the most diverse experience of Nairobi of the three works. But perhaps limited by the idea that fiction must document the ugliness that politics censors or hides, most of the stories here are united by their exploration of what it means to be poor and survive violence in Nairobi. The Akashic Noir series in which the book was published does focus on crime fiction, so it is unsurprising that Nairobi’s underbelly becomes the central theme. Still, the stilted speech in some of the selections and the similarity in character arcs feel like a performance of city for an international audience, rather than fiction about ordinary life in the city. There is a burden weighing the book down: the unspoken notion that stories about poor people must focus on the ugliness of poverty in order to be authentic.

These books are hopefully part of a broader rebirth of Nairobi’s fiction after decades of authoritarianism. Kenyan publishing culture, though, is struggling. For example, take the magazine and publishing house Kwani?, founded by rising Kenyan literary star Binyavanga Wainaina, who died last year at the age of forty-eight. Kwani?, with Billy Kahora as managing editor, undoubtedly set the bar for the current generation of Kenyan writers by publishing edgy, provocative fiction in the languages that we speak but without the burden of truth-telling.

Today, though, Kwani? has all but collapsed under internal politics and management woes. Without a safe publishing space that focuses on Kenya as a market and an audience, Nairobi writers are forced to rely on foreign publishers that have a very narrow view of what African fiction can be—chasing whatever is left from the international market once Nigerians and South Africans have had their moment. There is less space to make literature about ourselves for ourselves than has been in many years. Indeed, it is telling of the state of publishing in Kenya that none of these three books are published by Kenyan publishers. Maganjo’s novel is self-published through the online self-publishing platform Tablo, while Kahora’s and Kimani’s works are published by Rwanda’s Huza Press and Nigeria’s Cassava Republic Press, respectively. As a result, South B’s Finest is peppered with notable editorial mistakes (beyond the rhythms of Sheng’) that detract from the overall cohesion of the book, even if the story still reads briskly, while the latter two lack the tics that would make them even more distinctly Nairobi books.

There are publishing houses in Kenya, including several local iterations of large academic presses like OUP and MacMillan, and small academic presses like Twaweza. But the collective decision to avoid antagonizing the state through the Moi years led them to abandon publishing all but heavy-handed, moralistic literature meant to be taught in school. Maganjo’s, Kahora’s, and Kimani’s work all bear the traces of this idea that “good books” have to deliver a moral lesson. They lack a truth that Kwani? saw keenly: despite the hardship, there is tremendous joy in being from and in Nairobi. One doesn’t have to work hard to see Nairobi’s failings: they are tattooed on the city’s skin as gaping sewers, absent pavements, and choking traffic. What is harder to tap into is the joie de vivre and rhythms that keep us here and sane. Idle gossip by the mutura stand at dusk. Jacaranda trees that bloom after the cold, dreary days of August and September. The energy and creativity of a city that refuses to collapse into itself no matter what.

Granted, this focus on the harshness of life may be a broader challenge with African literary fiction in general, which implicitly pushes writers to wallow in their wounds and not their glories. But once a work of fiction has established bona fides as a sort of anthropological account, its ability to express joy can be blunted. Nairobi readers of contemporary fiction may be left still longing for a story about a Nairobian who has sex, smokes a blunt, or has a beer without their life unraveling into a cautionary tale. Regardless, these books are a declaration of intent. Despite the numerous setbacks and challenges that Nairobi writers face, they refuse to give up on telling the city’s stories. These are stories about the lines that divide us in the language that unites us: a reminder that a city is more than buildings and the economy.