By Nafeesa Syeed

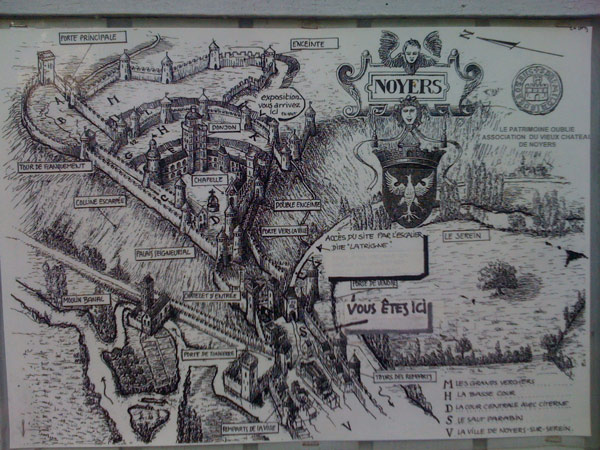

More than 300 wooden steps snake upward through dense forest to Le Chateau de Noyers sur Serein. It is slightly before dusk, in the province of Burgundy in central France. Scaffolding encircles a stout tower, almost fully restored. Layers of crumbling medieval stone spill from another tower, split in half. No one is at the ruins, save modern gargoyles, cut from white slabs, strewn about. A poster with Gothic lettering, affixed to a blade-less guillotine, spells out in French, “The Lost Heritage: Association of the Old Castle of Noyers.”

The man behind the preservation efforts of the damaged structure is a 65-year-old Dutchman named Willem Adriaan de Bruyn. We meet in the main square of Noyers sur Serein—a village of some 700 people—surrounded by the tourism center, butcher, library, hotels, galleries and the town’s single late-night bar. The storefronts are owned by a mix of long-time locals and newcomers who’ve set up shop.

As a child in The Netherlands, he earned the nickname “ Little Debris,” from playing in the rubble of buildings destroyed during World War II.

The past has always played a role in de Bruyn’s present. As a child in The Netherlands, he earned the nickname “ Little Debris,” from playing in the rubble of buildings destroyed during World War II. His family also owned a small Dutch castle further piquing an interest in history that eventually led him to study archaeology in college.

De Bruyn now drives a dusty white Renault work van. Daily, he heads down Noyers’ main road—beneath which there was once a moat—beside the Serein river, which hems the town. With one hand on the steering wheel and another clutching his Holland-imported beer, de Bruyn points out eight cylindrical towers, some dating to the 12th century, en route to his home. In between swigs and waves to familiar faces, he explains that these towers and the stone wall along the perimeter of the town once comprised an elaborate “defense system” protecting Noyers from rival rulers and even an attack from the forces of France’s Queen Blanche de Castille in the 13th century.

Next to 200-year-old linden trees is a centuries-old gate leading out of town. The chateau rests on the adjacent hill. From here, at Noyers’ edge, the huddled red rooftops of the village give way to the expanse beyond of dry wheat fields and meadows with reddish-brown cows. “There are some moments when you have the same view from 400 years ago,” de Bruyn says.

When Henry IV opted to follow Catholicism at a time of religious conflict in France, he ordered that the townspeople destroy the Protestant-owned chateau.

The chateau started out as a modest structure built by Noyers’ local feudal lords in the 10th century. In the 12th century, their descendants expanded the castle into a stately fortified compound. A few hundred years later, with no male heir to continue the line, the chateau was sold to the Dukes of Burgundy. When Henry IV opted to follow Catholicism at a time of religious conflict in France, he ordered that the townspeople destroy the Protestant-owned chateau. In 1599, all was demolished except for a wall and a few of the castle’s rear towers. The monarch made one concession: upon ruination, residents could use the chalk stone rubble for their own purposes. That stone, de Bruyn says, made its way into stairs, window openings, chimneys and fixtures across the village. “Every house in the town has something of the castle in the interior and exterior,” he says. Some people also built their homes into the remaining towers of the defense system that dot the main road below the chateau. For years, de Bruyn himself lived in one such refurbished, cone-topped tower.

It’s August and de Bruyn’s nose and cheeks are sunburnt. He wears a t-shirt and grey cargo pants. White locks fall to his ears. Like others of creative persuasion who’ve flocked to Noyers for its historic beauty, de Bryun settled here in 1989, working as an artist in media ranging from watercolor to sculpture. A former college art instructor, he explains how he and a neighbor, Daniel Robert, witnessed the “degradation” of the forgotten chateau remains during their walks up the hill. “It was hidden,” he says. “It was overwhelmed by ivy, by nature, by everything that overwhelms stone. We said, ‘This is a forgotten heritage, we have to protect it.”

They set up the “Lost Heritage” organization about 15 years ago and began salvaging the wrecked castle’s remnants. At first, some villagers told the two that they were mad, but de Bruyn says naysayers ultimately came around and showed their support “with their hands and donations.” The association has since implemented a program that brings students and other volunteers from various countries to work in masonry, using traditional methods to cut and lay stone—the same kind of chalk used in the original—to restore the castle and its grounds.

Sitting near his home, not far from the chateau, as de Bruyn ticks off dates and details about the castle’s architecture and history, we’re interrupted by Russian tourists asking for directions to the restored ruins. De Bruyn takes the college-aged girl and her parents to his garage covered with renderings of the medieval grounds and visitor pamphlets. “We don’t want to lose it,” he tells them, imparting a quick history lesson before they hike on.

De Bruyn, a sturdy figure, says he devotes about three months each year just to the physical work of repairing the castle. In spearheading the restoration, it helped that Robert, his neighbor and president of their organization, was a Noyers native. Though he is “fully accepted” by the townsfolk, de Bruyn says he was glad to take the vice presidency, below Robert, in case any skeptics jabbed: “Why do we need a Dutch guy arranging our history?” De Bruyn says Noyers is now a “melting pot” with original village dwellers and farmers mingling with recent transplants, who are more open to art, culture, theater and music.

Noyers, on France’s so-called “most beautiful villages” list, has long been a heritage tourism destination, the kind of place families might stop through while touring historic Burgundy in the summers. But nearby areas boasted more intact castles. De Bruyn says the rehabilitation of the chateau, starting in 1998, has been a boon for the town. As his group spread the word about their work, framing it as a kind of archaeological excavation, the castle has drawn thousands of tourists and generated economic benefits, and this success has garnered more local support for the work.

But, I ask him, who will be left to continue the chateau’s restoration when most young people are leaving to search for work elsewhere? It’s a small-town problem only exacerbated by the euro zone crisis and ever-disappearing employment opportunities. “I’m not afraid of what’s going to happen in the future of this site,” he says. Though there have been difficult times, de Bruyn is convinced that the young people from Noyers who’ve worked with him from the start—who are now in their thirties—will stay committed to the cause, and the same will be the case for the current generation. “And they are more and more and more interested,” he says. “I am satisfied, finally, there will be younger people who can take over the project who are from the town.”

Chilly gusts rip across the chateau grounds one morning as de Bruyn’s van rumbles onto the gravel drive. Sixteen teenagers, from France’s girl scout and boy scout organization, trek up the precarious stairway and catch their breath as they trickle in. They’ve come from Metz, a city 200 miles away, along German border. De Bruyn instructs the youth on their day’s work: helping construct the third row of a new amphitheater—an innovation facing the towers—designed by de Bruyn and modeled off of a Roman amphitheater. He hopes innovations like this will help make the grounds an artistic and cultural gathering space.

“For you and for me and for us, it’s such a mysterious place.”

Earlier De Bruyn had told me: “I always want to show my knowledge, transfer my knowledge to young people and that gives me my energy.” Now he models each task before the scouts mimic his action. Clad in shorts and jeans, the scrawny adolescents don yellow hardhats. A few boys shovel a mixture of sand and dirt into buckets, and then dump the contents into a cement mixer, whose motor gives off a gassy odor. Another batch of scouts transfers the viscid, dark-grey substance by wheelbarrow down to the crescent-shaped amphitheater.

After watching de Bruyn, three girls, one by one, plunge their shovels into the wheelbarrow and deposit the cement on the amphitheater’s chalk-stone stands. “Oh la la,” one of the girls says upon completing her chore. They smooth out clumps with the backs of their shovels. Meanwhile, others haul dollies loaded with jagged rocks down the hill, and heave the stones onto the moist sealant, creating back supports for a row of seats.

As the kids work, de Bruyn takes me to a lookout point with a spectacular view of the town, river and endless, elevated fields of gold and green. Staring out, he says the vista leaves the onlooker overwhelmed and in wonderment–a feeling that mirrors a child’s fascination. “For you and for me and for us, it’s such a mysterious place.”

Nafeesa Syeed is a freelance writer and editor based in Washington, currently co-writing a book on Arab women entrepreneurs. She completed a narrative writing masterclass at La Porte Peinte Centre Pour Les Arts in Noyers. You can follow her @NafeesaSyeed.